Neurodevelopmental disorder

Neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of disorders that affect the development of the nervous system, leading to abnormal brain function[1] which may affect emotion, learning ability, self-control, and memory. The effects of neurodevelopmental disorders tend to last for a person's lifetime.

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

Types

Neurodevelopmental disorders[2] are impairments of the growth and development of the brain and/or central nervous system. A narrower use of the term refers to a disorder of brain function that affects emotion, learning ability, self-control and memory which unfolds as an individual develops and grows.

The neurodevelopmental disorders currently considered, recognised and/or acknowledged to be as such are:

- Intellectual disability (ID) or intellectual and developmental disability (IDD), previously called mental retardation

- Specific learning disorders, like dyslexia or dyscalculia.

- Autistic spectrum disorders, such as autism or Asperger syndrome

- Motor disorders including developmental coordination disorder and stereotypic movement disorder

- Tic disorders including Tourette's syndrome

- Traumatic brain injury (including congenital injuries such as those that cause cerebral palsy[3])

- Communication, speech and language disorders

- Genetic disorders, such as fragile-X syndrome, Down syndrome,[4] attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, schizotypal disorder, hypogonadotropic hypogonadal syndromes[5]

- Disorders due to neurotoxicants like fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Minamata disease caused by mercury, behavioral disorders including conduct disorder etc. caused by other heavy metals, such as lead, chromium, platinum etc., hydrocarbons like dioxin, PBDEs and PCBs, medications and illegal drugs, like cocaine and others.

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Presentation

Consequences

The multitude of neurodevelopmental disorders span a wide range of associated symptoms and severity, resulting in different degrees of mental, emotional, physical, and economic consequences for individuals, and in turn families, social groups, and society.

Causes

The development of the nervous system is tightly regulated and timed; it is influenced by both genetic programs and the environment. Any significant deviation from the normal developmental trajectory early in life can result in missing or abnormal neuronal architecture or connectivity.[6] Because of the temporal and spatial complexity of the developmental trajectory, there are many potential causes of neurodevelopmental disorders that may affect different areas of the nervous system at different times and ages. These range from social deprivation, genetic and metabolic diseases, immune disorders, infectious diseases, nutritional factors, physical trauma, and toxic and environmental factors. Some neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism and other pervasive developmental disorders, are considered multifactorial syndromes which have many causes that converge to a more specific neurodevelopmental manifestation.[7]

Social deprivation

Deprivation from social and emotional care causes severe delays in brain and cognitive development.[8] Studies with children growing up in Romanian orphanages during Nicolae Ceauşescu's regime reveal profound effects of social deprivation and language deprivation on the developing brain. These effects are time-dependent. The longer children stayed in negligent institutional care, the greater the consequences. By contrast, adoption at an early age mitigated some of the effects of earlier institutionalization (abnormal psychology).[9]

Genetic disorders

A prominent example of a genetically determined neurodevelopmental disorder is Trisomy 21, also known as Down syndrome. This disorder usually results from an extra chromosome 21,[10] although in uncommon instances it is related to other chromosomal abnormalities such as translocation of the genetic material. It is characterized by short stature, epicanthal (eyelid) folds, abnormal fingerprints, and palm prints, heart defects, poor muscle tone (delay of neurological development) and intellectual disabilities (delay of intellectual development).[4]

Less commonly known genetically determined neurodevelopmental disorders include Fragile X syndrome. Fragile X syndrome was first described in 1943 by J.P. Martin and J. Bell, studying persons with family history of sex-linked "mental defects".[11] Rett syndrome, another X-linked disorder, produces severe functional limitations.[12] Williams syndrome is caused by small deletions of genetic material from chromosome 7.[13] The most common recurrent Copy Number Variannt disorder is 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (formerly DiGeorge or velocardiofacial syndrome), followed by Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome.[14]

Immune dysfunction

Immune reactions during pregnancy, both maternal and of the developing child, may produce neurodevelopmental disorders. One typical immune reaction in infants and children is PANDAS,[15] or Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection.[16] Another disorder is Sydenham's chorea, which results in more abnormal movements of the body and fewer psychological sequellae. Both are immune reactions against brain tissue that follow infection by Streptococcus bacteria. Susceptibility to these immune diseases may be genetically determined,[17] so sometimes several family members may suffer from one or both of them following an epidemic of Strep infection.

Infectious diseases

Systemic infections can result in neurodevelopmental consequences, when they occur in infancy and childhood of humans, but would not be called a primary neurodevelopmental disorder. For example HIV[18] Infections of the head and brain, like brain abscesses, meningitis or encephalitis have a high risk of causing neurodevelopmental problems and eventually a disorder. For example, measles can progress to subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

A number of infectious diseases can be transmitted congenitally (either before or at birth), and can cause serious neurodevelopmental problems, as for example the viruses HSV, CMV, rubella (congenital rubella syndrome), Zika virus, or bacteria like Treponema pallidum in congenital syphilis, which may progress to neurosyphilis if it remains untreated. Protozoa like Plasmodium[18] or Toxoplasma which can cause congenital toxoplasmosis with multiple cysts in the brain and other organs, leading to a variety of neurological deficits.

Some cases of schizophrenia may be related to congenital infections though the majority are of unknown causes.[19]

Metabolic disorders

Metabolic disorders in either the mother or the child can cause neurodevelopmental disorders. Two examples are diabetes mellitus (a multifactorial disorder) and phenylketonuria (an inborn error of metabolism). Many such inherited diseases may directly affect the child's metabolism and neural development[20] but less commonly they can indirectly affect the child during gestation. (See also teratology).

In a child, type 1 diabetes can produce neurodevelopmental damage by the effects of excess or insufficient glucose. The problems continue and may worsen throughout childhood if the diabetes is not well controlled.[21] Type 2 diabetes may be preceded in its onset by impaired cognitive functioning.[22]

A non-diabetic fetus can also be subjected to glucose effects if its mother has undetected gestational diabetes. Maternal diabetes causes excessive birth size, making it harder for the infant to pass through the birth canal without injury or it can directly produce early neurodevelopmental deficits. Usually the neurodevelopmental symptoms will decrease in later childhood.[23]

Phenylketonuria, also known as PKU, can induce neurodevelopmental problems and children with PKU require a strict diet to prevent mental retardation and other disorders. In the maternal form of PKU, excessive maternal phenylalanine can be absorbed by the fetus even if the fetus has not inherited the disease. This can produce mental retardation and other disorders.[24][25]

Nutrition

Nutrition disorders and nutritional deficits may cause neurodevelopmental disorders, such as spina bifida, and the rarely occurring anencephaly, both of which are neural tube defects with malformation and dysfunction of the nervous system and its supporting structures, leading to serious physical disability and emotional sequelae. The most common nutritional cause of neural tube defects is folic acid deficiency in the mother, a B vitamin usually found in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and milk products.[26][27] (Neural tube defects are also caused by medications and other environmental causes, many of which interfere with folate metabolism, thus they are considered to have multifactorial causes.)[28][29] Another deficiency, iodine deficiency, produces a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders ranging from mild emotional disturbance to severe mental retardation. (see also congenital iodine deficiency syndrome)

Excesses in both maternal and infant diets may cause disorders as well, with foods or food supplements proving toxic in large amounts. For instance in 1973 K.L. Jones and D.W. Smith of the University of Washington Medical School in Seattle found a pattern of "craniofacial, limb, and cardiovascular defects associated with prenatal onset growth deficiency and developmental delay" in children of alcoholic mothers, now called fetal alcohol syndrome, It has significant symptom overlap with several other entirely unrelated neurodevelopmental disorders.[30] It has been discovered that iron supplementation in baby formula can be linked to lowered I.Q. and other neurodevelopmental delays.[31]

Physical trauma

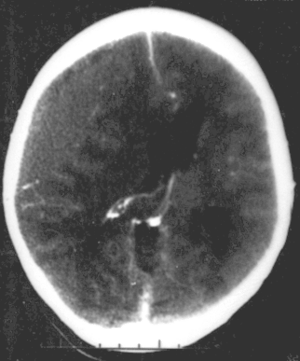

Brain trauma in the developing human is a common cause (over 400,000 injuries per year in the US alone, without clear information as to how many produce developmental sequellae)[32] of neurodevelopmental syndromes. It may be subdivided into two major categories, congenital injury (including injury resulting from otherwise uncomplicated premature birth)[3] and injury occurring in infancy or childhood. Common causes of congenital injury are asphyxia (obstruction of the trachea), hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain) and the mechanical trauma of the birth process itself.

Diagnosis

Neurodevelopmental disorders are diagnosed by evaluating the presence of characteristic symptoms or behaviors in a child, typically after a parent, guardian, teacher, or other responsible adult has raised concerns to a doctor.[33]

Neurodevelopmental disorders may also be confirmed by genetic testing. Traditionally, disease related genetic and genomic factors are detected by karyotype analysis, which detects clinically significant genetic abnormalities for 5% of children with a diagnosed disorder. As of 2017, chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) was proposed to replace karyotyping because of its ability to detect smaller chromosome abnormalities and copy-number variants, leading to greater diagnostic yield in about 20% of cases.[14] The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend CMA as standard of care in the US.[14]

Bibliography

- Tager-Flusberg, Helen (1999). Neurodevelopmental disorders. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-20116-2.

- Brooks, David R.; Walter Wolfgang Fleischhacker (2006). Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-26291-7.

Notes

- Rutter, Michael; Cooper, Miriam; Thapar, Anita (2017-04-01). "Neurodevelopmental disorders". The Lancet Psychiatry. 4 (4): 339–346. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5. ISSN 2215-0366. PMID 27979720.

- Reynolds, Cecil R.; Goldstein, Sam (1999). Handbook of neurodevelopmental and genetic disorders in children. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-1-57230-448-2.

- Murray RM, Lewis SW (September 1987). "Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder?". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 295 (6600): 681–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.295.6600.681. PMC 1247717. PMID 3117295.

- Facts about down syndrome Archived 2012-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Hernan Valdes-Socin, Matilde Rubio Almanza, Mariana Tomé Fernández-Ladreda, et al. Reproduction, smell, and neurodevelopmental disorders: genetic defects in different hypogonadotropic hypogonadal syndromes. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2014, 5: 109. review

- Pletikos, Mihovil; Sousa, Andre MM; et al. (22 January 2014). "Temporal Specification and Bilaterality of Human Neocortical Topographic Gene Expression". Neuron. 81 (2): 321–332. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.018. PMC 3931000. PMID 24373884.

- Samaco RC, Hogart A, LaSalle JM (February 2005). "Epigenetic overlap in autism-spectrum neurodevelopmental disorders: MECP2 deficiency causes reduced expression of UBE3A and GABRB3". Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 (4): 483–92. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi045. PMC 1224722. PMID 15615769.

- van IJzendoorn, Marinus H (Dec 2011). "Children in Institutional Care: Delayed Development and Resilience". Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 76 (4): 8–30. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00626.x. PMC 4130248. PMID 25125707.

- Nelson C.A.; et al. (2007). "Cognitive Recovery in Socially Deprived Young Children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project". Science. 318 (5858): 1937–1940. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1937N. doi:10.1126/science.1143921. PMID 18096809.

- Diamandopoulos, Katrina; Green, Janet (October 2018). "Down syndrome: An integrative review". Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 24 (5): 235–241. doi:10.1016/j.jnn.2018.01.001.

- Martin JP, Bell J (1943). "A pedigree of mental defect showing sex-linkage". J. Neurol. Psychiatry. 6 (3–4): 154–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.6.3-4.154. PMC 1090429. PMID 21611430.

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY (October 1999). "Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2". Nat. Genet. 23 (2): 185–8. doi:10.1038/13810. PMID 10508514.

- Merla G, Howald C, Henrichsen CN, et al. (August 2006). "Submicroscopic Deletion in Patients with Williams-Beuren Syndrome Influences Expression Levels of the Nonhemizygous Flanking Genes". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 (2): 332–41. doi:10.1086/506371. PMC 1559497. PMID 16826523.

- Christa Lese Martin, David H. Ledbetter. Chromosomal Microarray Testing for Children With Unexplained Neurodevelopmental Disorders JAMA. 2017;317(24):2545–2546. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7272 June 27, 2017

- Pavone, P.; et al. (2004). "Anti-brain antibodies in PANDAS versus uncomplicated streptococcal infection" (PDF). Pediatr Neurol. 30 (2): 107–110. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(03)00413-2. hdl:2108/194065. PMID 14984902.

- Dale, RC.; et al. (2005). "Incidence of anti-brain antibodies in children with obsessive–compulsive disorder". Br J Psychiatry. 187 (4): 314–319. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.4.314. PMID 16199788.

- Swedo, Susan E (December 2001). "Genetics of childhood disorders: XXXIII autoimmunity part 6: poststreptoccoal autoimmunity". Reprinted from J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 40:12,1479-1482. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- Bolvin, MJ; Kakooza, AM; Warf, BC; Davidson, LL; Grigorenko, EL (November 2015). "Reducing neurodevelopmental disorders and disability through research and interventions". Nature. 527 (7578): S155–60. Bibcode:2015Natur.527S.155B. doi:10.1038/nature16029. PMID 26580321.

- Brown, Alan S. (April 2006). "Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia – Brown 32 (2): 200 – Schizophrenia Bulletin". Schizophrenia Bulletin. pp. 200–202. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj052. PMC 2632220. PMID 16469941. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Richardson, A.J.; Ross, M.A. (July 2000). "Fatty acid metabolism in neurodevelopmental disorder: a new perspective on associations between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and the autistic spectrum". Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 63 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.1054/plef.2000.0184. PMID 10970706.

- Nordham, Elizabeth A; Anderson, PJ; Jacobs, R; Hughes, M; Warne, GL; Werther, GA; et al. (2001). "Neuropsychological Profiles of Children With Type 1 Diabetes 6 Years After Disease Onset". Diabetes Care. 24 (9): 1541–1546. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.9.1541. PMID 11522696.

- Olsson, Gunilla M.; Hulting, AL; Montgomery, SM; et al. (2008). "Cognitive Function in Children and Subsequent Type 2 Diabetes: Response to Batty, Gale, and Deary". Diabetes Care. 31 (3): 514–516. doi:10.2337/dc07-1399. PMC 2453642. PMID 18083794.

- Ornoy A, Wolf A, Ratzon N, Greenbaum C, Dulitzky M (July 1999). "Neurodevelopmental outcome at early school age of children born to mothers with gestational diabetes". Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 81 (1): F10–4. doi:10.1136/fn.81.1.F10. PMC 1720965. PMID 10375355.

- Lee PJ, Ridout D, Walter JH, Cockburn F (February 2005). "Maternal phenylketonuria: report from the United Kingdom Registry 1978-97". Arch. Dis. Child. 90 (2): 143–6. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.037762. PMC 1720245. PMID 15665165.

- Rouse B, Azen C, Koch R, et al. (March 1997). "Maternal Phenylketonuria Collaborative Study (MPKUCS) offspring: facial anomalies, malformations, and early neurological sequelae". Am. J. Med. Genet. 69 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970303)69:1<89::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9066890.

- "Folic Acid - March of Dimes".

- "Folate (Folacin, Folic Acid)".

- "Folic scid: topic home". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- "The basics about spina bifida". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- Fetal alcohol syndrome: guidelines for referral and diagnosis (PDF). CDC (July 2004). Retrieved on 2007-04-11

- Kerr, Martha; Désirée Lie (2008). "Neurodevelopmental delays associated with iron-fortified formula for healthy infants". Medscape Psychiatry and Mental Health. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- "Facts About TBI" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders (PDF), America's Children and the Environment (3 ed.), EPA, August 2017, p. 12, retrieved 2019-07-10

External links

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders at Curlie

- A Review of Neurodevelopmental Disorders - Medscape review