Niš

Niš (/ˈniːʃ/; Serbian Cyrillic: Ниш, pronounced [nîːʃ] (![]()

Niš | |

|---|---|

| City of Niš | |

From top: Panoramic view of Niš, Niš Fortress, Bubanj Memorial Park, Monument on Čegar, Nišava river, Palace of Justice, Church of the Holy Emperor Constantine and Empress Helena, University of Niš | |

| Nickname(s): "Second capital"[1] "The Emperor's City" | |

Niš Location within Serbia  Niš Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 43°19′15″N 21°53′45″E | |

| Country | Serbia |

| Region | Southern and Eastern |

| District | Nišava |

| Municipalities | 5 |

| First mention | 2nd century AD |

| Liberation from Ottomans | 11 January 1878 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Darko Bulatović (SNS) |

| • Ruling parties | SNS/SPS/SRS |

| • Legislature | City Assembly of Niš |

| Area | |

| • City | 596.73 km2 (230.40 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 266.77 km2 (103.00 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,729 km2 (1,054 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 51st in Serbia |

| Elevation | 195 m (640 ft) |

| Population (2011)[3] | |

| • City | 260,237 |

| • Rank | 3rd in Serbia |

| • Density | 431.1/km2 (1,117/sq mi) |

| • City Proper | 183,164 |

| Demonym(s) | Nišlijka (female) Nišlija (male) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 18000 |

| Area code(s) | +381(0)18 |

| ISO 3166 code | SRB |

| Car plates | NI |

| Patron Saint | Procopius of Scythopolis[4] |

| Website | www |

Niš is the city of three Roman emperors: Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor and the founder of Constantinople; Constantius III; and Justin I. Later playing a prominent role in the history of the Byzantine Empire, the city's past would earn it the nickname The Emperor's City.[5][6]

After about 400 years of Ottoman rule, the city was liberated in 1878 and became part of the Principality of Serbia, though not without great bloodshed—remnants of which can be found throughout the city. Today, Niš is one of the most important economic centers in Serbia, especially in the electronics, mechanical engineering, textile, and tobacco industries. Constantine the Great Airport is Niš's international airport.

In 2013, the city was host to the celebration of 1700 years of Constantine's Edict of Milan.[7]

Name

The town was named after the Nišava River, which flows through the city. It was first named Navissos by Celtic tribes in the 3rd century BC. From this term comes the Latin Naissus, the Greek Nysos and the Slavic Niš.[5] Other variations include: Νάϊσσος, Ναϊσσός (Naissos), Naessus, urbs Naisitana, Navissus, Navissum, Ναϊσσούπολις (Naissoupolis). In Old Serbian, the town was known as Niš (written Нишь and Ньшь). The name is historically rendered as Nish or Nissa in English.[8]

History

Early history

Archaeological evidence shows Neolithic settlements in the city and its surroundings dating from 5,000 to 2,000 BC.[9] A notable archaeological site is Humska Čuka, in the nearby settlement of Hum. In the Iron Age, the Thracians dominated the region, with one of their chief settlements being the nearby Aiadava; specifically, the Triballi are mentioned as inhabiting this region as early as 424 BC. In 279 BC, during the Gallic invasion of the Balkans, the Celtic Scordisci defeated the Triballi and founded the city as Navissos.[10] During the Roman conquest of the Balkans between 168 and 75 BC, the city, known as Naissus in Latin, was used as a base of operations. Naissus was first mentioned in Roman documents near the beginning of the 2nd century CE, and was considered a place worthy of note in the Geography of Ptolemy of Alexandria.

The Romans occupied the town during the Dardanian campaign (75-73 BC), and set up a legionary camp in the city.[11] The city, called refugia and vici in pre-Roman relation, as a result of its strategic position (the Thracians were based to the south[11]) developed as an important garrison and market town in the province of Moesia Superior.[12] In 272 AD, the future Emperor Constantine the Great was born in Naissus. Constantine created the Dacia Mediterranea province, of which Naissus was the capital, which also included Remesiana on the Via Militaris and the towns of Pautalia and Germania. He lived in Naissus briefly from 316 to 322.[13]

In 364 AD, the imperial Villa Mediana 3 km (2 mi) was the site where emperors Valentinian and Valens met and divided the Roman Empire into halves which they would rule as co-emperors[14]

It was besieged by the Huns in 441 and devastated in 448, and again in 480 when the partially-rebuilt town was demolished by the Barbarians. Byzantine Emperor Justinian I restored the town but it was destroyed by the Avars once again. The Slavs, in their campaign against Byzantium, conquered Niš and settled here in 540.

Middle Ages

In 805, the town and its surroundings were taken by Bulgarian Emperor Krum.[15] In the 11th century Byzantium reclaimed control over Niš and the surrounding area.

During the People's Crusade, on July 3, 1096, Peter the Hermit clashed with Byzantine forces at Niš. Manuel I fortified the town, but under his successor Andronikos I it was seized by the Hungarian king Béla III. Byzantine control was eventually reestablished, but in 1185 it fell under Serbian control. By 1188, Niš became the capital of Serbian king Stefan Nemanja.[16] On July 27, 1189, Nemanja received German emperor Frederick Barbarossa and his 100,000 crusaders at Niš.[17] Niš is mentioned in descriptions of Serbia under Vukan in 1202, highlighting its special status.[18] In 1203, Kaloyan of Bulgaria annexed Niš.[19] Stefan Nemanjić later regained the region.

Ottoman period

The fall of the Serbian Empire, which was conquered by Ottoman Sultan Murad I in 1385, decided the fate of Niš as well. After a 25-day-long siege the city fell to the Ottomans. It was returned to Serbian rule in 1443. Niš again fell under Ottoman rule in 1448, and remained thusly for 241 years. During Ottoman rule Niš was a seat of the empire's military and civil administration. A Silesian traveler stated in 1596 that the route from Sofia to Niš was littered with corpses and described the gates of Niš as bedecked with the freshly-severed heads of poor Bulgarian peasants.[20] In 1689, Niš was seized by the Austrian army during the Great Turkish War, but the Ottomans regained it in 1690. In 1737, Niš was again seized by the Austrians, who attempted to rebuild the fortifications around the city. The same year, the Ottomans reclaimed the city without resistance.

During the First Serbian Uprising in 1809, Serbian revolutionaries attempted to liberate Niš in the Battle of Čegar. After the defeat of the Serbian forces, the Ottoman commander of Niš ordered the heads of the slain Serbs mounted on a tower to serve as a warning. The structure became known as Skull Tower (Serbian: Ćele Kula).[21] In 1821, the Ottomans arrested the Bishop of Niš, Milentija, as well as 200 Serbian patriots, on charges of preparing an uprising in the Niš area in support of the Greek War of Independence. On June 13 of that year, Bishop Milentija and other Serbian leaders were hanged in public.

In the 19th century Niš was an important town, but populated by Bulgarians in the 19th century, when the Niš rebellion broke out in 1841.[22] According to Ottoman statistics during the Tanzimat the population of Sanjak of Niš was treated as Bulgarian,[23] and according to French travelers such as Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui and Ami Boue in 1837/1841. According to all authors between 1840-72 the delineation between Bulgarians and Serbs is undisputed and ran north of Nis,[24] although one author Cyprien Robert claims that half of the population of the town was made up by Serbians.[25] Serbian cartographers of the time (such as Dimitrije Davidović in 1828 and Milan Savić in 1878) also accepted South Morava river as such delineation and added Niš outside the borders of the Serbian people.[24][26] The urban Muslim population of Niš consisted mainly of Turks, of which a part were of Albanian origin, and the rest were Muslim Albanians and Muslim Romani.[27][28]

In 1870, Niš was included in the Bulgarian Exarchate.[29] Before the area had been under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć. The city was also stipulated the area to be ceded to Bulgaria according to the Constantinople Conference in 1876.[30] Niš was finally liberated during the Serbo–Ottoman War of 1876–1878. The battle for the liberation of Niš started on 29 December 1877 and the Serbian Army entered Niš on 11 January 1878 and it became a part of Serbia. The Albanian quarter was burned and some of the town's Muslim population fled to the Ottoman vilayet of Kosovo, resettling in Pristina, while others went to Skopje.[27][31][28] The number of remaining Muslims counted were 1,168, with many being Muslim Romani, out of the pre-war ca. 8,500.[32][28] The demographics of Niš underwent change whereby Serbs who formed half the urban population prior to 1878 became 80 percent in 1884.[33]

Independent Serbia

In the following years, the city saw rapid development. The city library was founded in 1879, and its first clerk was Stevan Sremac. The first hotel, Europe, was built in 1879; shortly after a hospital and the first bank started operating in 1881. In 1878, the first Grammar School (Gimnazija), in 1882 the Teacher Training College, and in 1894, the Girls' College were founded in Niš. In 1895, Niš had one girls' and three boys' primary schools. The City Hall was built from 1882–87.

In 1883, Kosta Čendaš established the first printing house. In 1884, the first newspaper in the city Niški Vesnik was started. In 1884, Jovan Apel built a brewery. A railway line to Niš was built in 1884, as well as the city's railway station; on 8 August 1884, the first train arrived from Belgrade. In 1885, Niš became the last station of the Orient Express, until the railroad was built between Niš and Sofia in 1888. In 1887, Mihailo Dimić founded the "Niš Theatre Sinđelić."

In 1897 Mita Ristić founded the Nitex textile factory. In 1905 the female painter Nadežda Petrović established the Sićevo art colony. The first film was screened in 1897, and the first permanent cinema started operating in 1906.[34] The hydroelectric dam in Sićevo Gorge on the Nišava was built in 1908; at the time, it was the largest in Serbia. The airfield was built in 1912 on the Trupale field, and the first aeroplane arrived on 29 December 1912. City Museum was founded in 1913, hosting archaeological, ethnographic and art collections.

During the First Balkan War, Niš was the seat of The Main Headquarters of the Serbian Army, which led military operations against the Ottoman Empire. In World War I, Niš was the wartime capital of Serbia, hosting the Government and the National Assembly, until Central Powers conquered Serbia in November 1915, when the city was ceded to Bulgaria. After the breakthrough of the Salonika Front, the First Serbian Army commanded by general Petar Bojović liberated Niš on 12 October 1918.

During the age and breakup of Yugoslavia

In the first few years after the war, Niš was recovering from the damage. In 1921, Niš became the centre of the Region (oblast), governed by a grand-župan, appointed by royal decree. From 1929–41, Niš was the capital of the Morava Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The tram system in Niš started to run in November 1930. The national airline Aeroput included Niš as a regular destination for the route Belgrade—Niš—Skopje—Thessaloniki in 1930. During the time of German occupation in World War II, the first Nazi concentration camp in Yugoslavia was in Niš. About 30,000 people passed through this camp, of whom over 10,000 were shot on nearby Bubanj hill. On 12 February 1942, 147 prisoners staged a mass escape. In 1944, the city was heavily bombed by the Allies.[35]

On 14 October 1944, after a long and exhausting battle, the 7th German SS Division 'Prinz Eugen' was defeated and Niš was liberated by Bulgarian Army,[36][37][38] and Partisans. The city was also the site of a unique and accidental friendly fire air war on November 7, 1944 between the air forces of the United States and Soviet Union. On June 23, 1948, Niš was the site of a catastrophic flood during which the Nišava river's water level raised by an unprecedented 5.5 meters.[39]

After World War II, the University of Niš was founded on 15 June 1965.

Over the course of the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, Niš was subject to airstrikes on 40 occasions.[40] On May 7, 1999, the city was the site of a NATO cluster bomb raid which killed up to 16 civilians.[40] By the end of the NATO bombing campaign, a total of 56 people in Niš had been killed from airstrikes.[40]

2000–present

In April 2012, the Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center was established in the city of Niš. In December 2017, a new building of Clinical Centre of Niš spreading over 45,000 square meters was opened.[41]

Geography

The road running from the North, from Western and Central Europe and Belgrade down to the Morava River valley, forks into two major lines at Niš: the southern line, leading to Thessalonica and Athens, and the eastern one leading towards Sofia and Istanbul.

Niš is situated at the 43°19' latitude north and 21°54' longitude east, in the Nišava valley, near the spot where it joins the South Morava. The main city square, the city's central part, is at 194 m (636 ft) above sea level. The highest point in the city area is "Sokolov kamen" (Falcon's rock) on the Suva Planina (Dry Mountain) (1,523 m (4,997 ft)) while the lowest spot is at Trupale, near the mouth of the Nišava (173 m (568 ft)). The city covers 596.71 square kilometres (230 sq mi) of five municipalities. Below Niska Banja and Nis, under the ground is a natural source of hot water, unique potential of clean and renewable geothermal energy at the surface of up to 65 square kilometers. The natural reservoir is at a depth of 500 to 800 meters, and the estimated capacity is about 400 million cubic meters of thermal mineral water.[42]

Climate

Niš has a humid subtropical climate, but with continental influences. Average annual temperature in the area of Niš is 11.9 °C (53.4 °F). July is the warmest month of the year, with an average of 22.5 °C (72.5 °F). The coldest month is January, averaging at 0.6 °C (33.1 °F). The average of the annual rainfall is 580.3 mm (22.85 in). The average barometer value is 992.74 mb. On average, there are 134 days with rain and snow cover lasts for 41 days.

| Climate data for Niš (1981–2010, extremes 1940–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.7 (71.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

40.3 (104.5) |

44.2 (111.6) |

42.2 (108.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

44.2 (111.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.7 (−10.7) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−23.7 (−10.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.8 (1.53) |

36.8 (1.45) |

42.5 (1.67) |

56.6 (2.23) |

58.0 (2.28) |

57.3 (2.26) |

44.0 (1.73) |

46.7 (1.84) |

48.0 (1.89) |

45.5 (1.79) |

54.8 (2.16) |

51.5 (2.03) |

580.3 (22.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 134 |

| Average snowy days | 10 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 37 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 74 | 66 | 63 | 65 | 65 | 61 | 61 | 69 | 73 | 77 | 81 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 64.5 | 93.3 | 147.8 | 171.5 | 220.9 | 251.2 | 286.7 | 274.3 | 201.9 | 150.5 | 85.9 | 49.4 | 1,997.7 |

| Source 1: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[44] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1878 | 12,801 | — |

| 1884 | 16,178 | +26.4% |

| 1890 | 19,877 | +22.9% |

| 1895 | 21,524 | +8.3% |

| 1900 | 24,573 | +14.2% |

| 1905 | 21,946 | −10.7% |

| 1910 | 24,949 | +13.7% |

| 1921 | 28,625 | +14.7% |

| 1931 | 35,465 | +23.9% |

| 1941 | 44,800 | +26.3% |

| 1948 | 49,332 | +10.1% |

| 1953 | 58,656 | +18.9% |

| 1961 | 81,250 | +38.5% |

| 1971 | 127,654 | +57.1% |

| 1981 | 161,376 | +26.4% |

| 1991 | 173,250 | +7.4% |

| 2002 | 173,724 | +0.3% |

| 2011 | 183,164 | +5.4% |

| Source: Становништво, национална или етничка припадност, подаци по насељима, Републички завод за статистику[45] | ||

According to the final results from the 2011 census, the population of city proper of Niš was 183,164,[3] while its administrative area had a population of 260,237.[3]

The city of Niš has 87,975 households with 2,96 members on average, while the number of homes is 119,196.[46]

Religion structure in the city of Niš is predominantly Serbian Orthodox (240,765), with minorities like Muslims (2,486), Catholics (809), Protestants (258), Atheists (109) and others.[47] Most of the population speaks Serbian language (249,949).[47]

The composition of population by sex and average age:[47]

- Male - 126,645 (40.90 years) and

- Female - 133,592 (42.81 years).

A total of 120,562 citizens (older than 15 years) have secondary education (53.81%), while the 51,471 citizens have higher education (23.0%). Of those with higher education, 34,409 (15.4%) have university education.[48]

Ethnic composition

The ethnic composition of the city of Niš:[49]

| Demographics of Niš | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | City | Urban |

| Serbs | 243,381 | 174,225 |

| Romani | 6,996 | 5,490 |

| Montenegrins | 659 | 579 |

| Bulgarians | 927 | 741 |

| Yugoslavs | 202 | 202 |

| Croats | 398 | 344 |

| Others | 7,674 | 1,963 |

| Total | 260,237 | 183,544 |

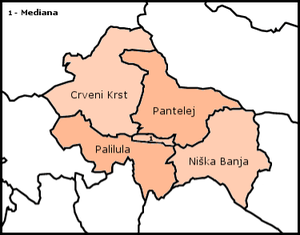

Administrative divisions

The city of Niš consists of five municipalities. The first four municipalities are in the urban area of Niš, while Niška Banja is a suburban municipality. Before 2002, the city of Niš had only two municipalities, one of them named "Niš" and another named "Niška Banja". The city of Niš includes further neighborhoods: | ||||

| Medijana | Palilula | Pantelej | Crveni Krst | Niška Banja |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | Palilula | Pantelej | Crveni Krst | Niška Banja |

| Marger | Staro Groblje | Jagodin Mala (partly) | Beograd Mala | Nikola Tesla (broj 6) |

| Trg Kralja Aleksandra | Crni put | Durlan | Jagodin Mala (partly) | Jelašnica |

| Kičevo | Bubanj | Komren (partly) | Komren (mostly) | Sićevo |

| Čair | Ledena Stena | Čalije | Šljaka | Ostrovica |

| Bulevar Nemanjića | Suvi Do | Somborski bulevar | Medoševac | Prva Kutina |

| Bulevar Djindjica | Apelovac | Vrežina | Ratko Jović | Radikina Bara |

| Medijana | Kovanluk | Branko Bjegović | Stevan Sindjelić | Prosek |

| Trošarina | Tutunović Podrum | Podvinik | Čukljenik | |

| Duvanište | Kalač Brdo | Beverli Hils | Donja and Gornja Studena | |

| Brzi Brod | Gabrovačka reka | |||

Economy

The city of Niš is the administrative, industrial, commercial, financial and cultural center of the south-eastern part of Republic of Serbia. The position of Niš is strategically important, at the intersection of European highway and railway networks connecting Europe with Asia. Niš is easily accessible, having an airport – Niš Constantine the Great Airport and being a point of intersection of numerous railroad and highway lines.

It is in Niš that the trunk road running from the north down the Morava River valley forks into two major lines:

- the south one, leading to Thessalonica and Athens, along the Vardar River valley,

- and the east one, running along the Nisava and the Marica, leading towards Sofia and Istanbul, and further on, towards the Near East.

These roads have been widely known from ancient times, because they represented the beaten tracks along which peoples, goods and armies moved. Known as 'Via Militaris' in Roman and Byzantine periods, or 'Constantinople road' in Middle Ages, these roads still represent major European traffic arteries. Niš thus stands at a point of intersection of the roads connecting Asia Minor to Europe, and the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Nis had been a relatively developed city in the former Yugoslavia. In 1981, its GDP per capita was 110% of the Yugoslav average.[50]

As of September 2017, Niš has one of 14 free economic zones established in Serbia.[51]

- Economic preview

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2019):[52]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 187 |

| Mining and quarrying | 140 |

| Manufacturing | 21,072 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 806 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 1,941 |

| Construction | 3,190 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 13,577 |

| Transportation and storage | 5,408 |

| Accommodation and food services | 3,541 |

| Information and communication | 3,077 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 1,446 |

| Real estate activities | 130 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 3,559 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 2,159 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 4,139 |

| Education | 7,261 |

| Human health and social work activities | 7,542 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 1,256 |

| Other service activities | 1,677 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 89 |

| Total | 82,197 |

Companies

Niš is one of the most important industrial centers in Serbia, well known for its tobacco, electronics, construction, mechanical-engineering, textile, nonferrous-metal, food-processing and rubber-goods industries.

Among the manufacturing companies which had a huge impact during the second half of 20th century on Niš's development are: EI Niš (electronics industry), Mechanical Industry Niš, "Građevinar" (construction company), Niš Tobacco Factory, "Nitex - Niš" (textile industry), "Niš Brewery" (beverages) and "Žitopek" (bakery). Other prominent companies which went bankrupt during the 1990s and 2000s are: "Vulkan" (rubber-goods manufacturer), "NISSAL" (nonferrous-metal industry).

Prominent tobacco manufacturer "Niš Tobacco Factory" was sold to Philip Morris in August 2003 for 518 million euros.[53]

Transportation

Niš is strategically between the Morava river valley in North and the Vardar river valley in the south, on the main route between Greece and Central Europe. In the Niš area, this major transportation and communication route is linked with the natural corridor formed by the Nišava river valley, which runs Eastwards in the direction of Sofia and Istanbul. The city has been a passing station for the Orient Express.

The first highways date back to the 1950s when Niš was linked with capital Belgrade through the Brotherhood and Unity Highway, the first in Central-Eastern Europe.

Historically, because of its location, the city had always great importance in the region. The first to take advantage of it was the Roman Empire that built the important road Via Militaris, linking the city with Singidunum (current Belgrade) to the North and Constantinople (current Istanbul) to the southeast. Nowadays, the city is connected by the highway E75 with Belgrade and Central Europe in north, and Skopje, Thessaloniki and Athens in the south. The road E80 connects Niš with Sofia, Istanbul towards the Middle East, and Pristina, Montenegro and the Adriatic Sea to the West. The road E771 connects the city with Zaječar, Kladovo and Drobeta-Turnu Severin in Romania.

The city is also a major regional railway junction linking Serbia to Sofia and Istanbul.

The Niš Constantine the Great airport is the second most important airport in Serbia. The first airfield serving the city of Niš was established in 1910, near the village of Donje Međurovo. In the 1930s then-national airline company Aeroput used the airport for civil service. In 1935 Aeroput included a stop in Niš in its route linking Belgrade with Skoplje.[54]

The city public transportation consists nowadays of 13 bus lines. A tram system existed in Niš between 1930 and 1958.[55] Niš Bus Station is the city's largest and main bus station which offers both local urban and intercity transport to international destinations. The largest intercity bus carrier based in the city is Niš-Ekspres, which operates to various cities and villages in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Culture

Theatre

Niš is a home of the National Theatre in Niš, that was founded as "Sinđelić" Theatre in 1889.

Music

From 1981 Niš is the host of Nišville International Jazz music festival which begins in mid-August and lasts for 4 days. Galija, Kerber and Eyot are considered the most notable music bands to have originated from Niš. Other notable Niš music acts include Daltoni, Dobri Isak, Lutajuća Srca, Mama Rock, Hazari, Novembar, Trivalia and others.

Tourism

Tourist sites

- Čegar – The place where Battle on Čegar Hill took place on 19 May 1809.

- Crveni Krst concentration camp – One of the few preserved Nazi concentration camps in Europe. It is on 12 February Boulevard.

- Memorial to Constantine the Great – built in the city centre in 2013, in commemoration to Constantine the Great who was born in the city, on the anniversary of the Edict of Milan.

- Bubanj – Monument to fallen Yugoslav World War II fighters, forming the shape of three clenched fists. The place where 10,000 civilian hostages from Niš and south Serbia were brutally murdered by German Nazis.

- Kalča, City passage and Gorča – Trade centers situated in Milana Obrenovića Street.

- Memorial Chapel in the memory of NATO bombing victims - The chapel was built by local authorities while the monument was built by the State government in 1999. They are situated in Sumatovacka street near Niš Fortress.

- Niš Fortress - The remaining fortification was built by the Turks, and dates from the first decades of the 18th century (1719–23). It is situated in the city center.

- The fortress-cafes - They are situated near Stambol gate (the main gate of the fortress).

- Mediana - Archeological site, an Imperial villa, from the late Roman period on the road leading to Sofia, Bulgaria, near EI Nis.

- Niška Banja (Niš spa) - A very popular spa during the summer season. It is 10 km (6 mi) from city center on the road leading to Sofia, in the bottom of Suva Planina Mountain.

- Tinkers Alley - An old urban downtown zone in today's Kopitareva Street, built in the first half of the 18th century. It was a street full of tinkers and other craftsmen, but today it is packed with cafes and restaurants.

- Skull Tower (Ćele Kula) - A monument to the Serbian revolutionaries (1804–13); a tower made out of skulls of Serbian uprisers, killed and decapitated by the Ottomans. It is situated on Zoran Đinđić Boulevard, on the old Constantinople road leading to Sofia.

- Sultans Trail Long distance hiking and biking route from Vienna to İstanbul runs through Niš.

Architecture and monuments

Buildings in Niš are constantly being built. Niš is the second largest city after Belgrade for number of high-rises. The Ambassador Hotel is one of the tallest buildings in Niš, but there are also other buildings like TV5 Tower.

Sport

The city of Niš is home to numerous sport clubs including Radnički Niš, RK Železničar 1949, Mašinac, ŽRK Naisa, OK Niš, Mašinac, Sinđelić Niš etc.

The biggest stadium in Niš is the Stadion Čair, which is currently undergoing renovations and will have a total seating-capacity of 18,151 when renovations are completed.[56] The stadium is part of the Čair Sports Complex that also includes an indoor swimming pool and an indoor arena. Niš was one of four towns which hosting the 2012 European Men's Handball Championship.

Notable residents

The people listed below were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with the city of Niš, and its surrounding metropolitan area.

- Constantine I, the great, (Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus) – ruled 306 to 337

- Constantius III, (Flavius Constantius) – ruled 421

- Justin I, (Flavius Iustinus) – ruled 518 to 527

- Stevan Sinđelić, war leader (vojvoda), died in 1809 in the Battle of Čegar.

- Stevan Sremac (1855–1906), writer, came to Niš shortly after its liberation from the Turkish rule; wrote about life in old Niš (Ivkova slava, Zona Zamfirova).

- Nikola Uzunović, (b. 1873), prime minister of Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1926 to 1927.

- Dragiša Cvetković, (1893–1969), prime minister of Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1939 to 1941.

- Svetislav Milosavljević, (1882–1960), a Yugoslav army general and first Ban of Vrbas Banovina.

- Dušan Radović, (1922–84), journalist and writer.

- Dušan Čkrebić, (b. 1927), President(1984–1986) and Prime Minister(1978–1982) of SR Serbia.

- Spiridon, (?–1389), Patriarch of Serbian Patriarchate of Peć.

- Irinej (b. 1930), Serbian patriarch (2010–) and Bishop of Niš (1975–2010)

- Nadja Regin, (1931–2019), Serbian and British actress.

- Predrag Antonijević, (b. 1959), film director.

- Branko Miljković (1934–61), poet.

- Bratislav Anastasijević (1936–1992), musician, conductor

- Šaban Bajramović (1936–2008), Romani singer and composer.

- Kornelije Kovač (b. 1942), rock musician and composer.

- Goran Paskaljević (b. 1947), movie director; raised by his grandparents in Niš 1949–63, after the divorce of his parents.

- Dragan Pantelić (b. 1951), former football goalkeeper, president of Radnički Niš.

- Eva Haljecka Petković (1870–1947), doctor.

- Predrag Miletić (b. 1952), actor.

- Miki Manojlović (b. 1950), actor.

- Zoran Živković (b. 1954), handball player and coach, Olympic champion

- Aki Rahimovski (b. 1954), rock musician.

- Nenad Milosavljević (b. 1954), rock musician.

- Biljana Krstić (b. 1959), rock and traditional music singer and songwriter.

- Ana Stanić (b.1975), Serbian pop-rock singer

- Zoran Živković (b. 1960), politician, a former Prime Minister of Serbia.

- Zoran Ćirić (b. 1962), writer.

- Aleksandar Šoštar (b. 1964), water polo goalkeeper, Olympic, World and European champion.

- Dragan Stojković (b. 1965), football player, Olympic bronze medalist.

- Lidija Mihajlović (b. 1968), shooting champion.

- Branislava Ilić (b. 1970), playwright, screenwriter, prose writer, essayist.

- Ivan Miljković (b. 1979), volleyball player, Olympic and European champion.

- Bojana Popović (b. 1979), Montenegrin handball player, Olympic silver medalist.

- Nikola Karabatić (b. 1984), French handball player, Olympic, World and European champion.

- Nemanja Radulović (b. 1985), violinist.

- Ivan Kostic (b. 1989), footballer.

- Stefan Jović (b. 1990), basketball player, Olympic, World Cup, and EuroBasket silver medalist.

- Sava Ranđelović (b. 1993), water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion.

- Andrija Živković (b. 1996), footballer, U-20 World champion.

- Staša Gejo (b. 1997), sport climber, World and European champion.

- Nemanja Radonjić (b. 1996), footballer, Serbian champion.

Local media

|

|

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Niš is twinned with the following cities, according to their City Hall website:[68]

Other forms of cooperation and city friendship

See also

References

- Protić, Stojan. Niš-Second Capital. Niš: Prosveta.

- "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- "ST PROCOPIUS".

- "City of Nis". Ni.rs. Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- "Latest news, Latest News Headlines, news articles, news video, news photos - UPI.com". Metimes.com. 2013-02-14. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- "Moderate Patriarch Sets New Course for Serb Church". IPS News. 2010-02-01. Archived from the original on 2010-02-10.

- Mišić (2010). Лексикон градова и тргова средњовековних српских земаља. p. 188.

- Stone Pages, 002763

- "Nis". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- Syme, Ronald (1999). The provincial at Rome: and, Rome and the Balkans 80BC-AD14, p. 207. ISBN 9780859896320. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- "BALCANICA XXXVII" (PDF). Balkaninstitut.com. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Pannonia and Upper Moesia: a history of the middle Danube provinces p.51

- "Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 2: Chapter XXV: Reigns Of Jovian And Valentinian, Division Of The Empire. Part II". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- Fine, John V. A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (29 December 1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472081493. Retrieved 29 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- The Late Medieval Balkans, p. 7

- The Late Medieval Balkans, p. 24

- The Late Medieval Balkans, p. 48

- The Late Medieval Balkans, p. 54

- Kultur der Nationen (in German). p. 110.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1982). "The Serbian Insurgents and the Russo-Turkish War of 1809–1812". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). First Serbian Uprising, 1804–1813. New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-930888-15-2.

- Chalcraft, John (2016-03-22). Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107007505.

- Pinson, Mark (May 1975). "Ottoman Bulgaria in the First Tanzimat Period: The Revolts in Nish (1841) and Vidin (1850)". Middle Eastern Studies. 11 (2): 103–146. doi:10.1080/00263207508700291. JSTOR 4282564.

- Light, Andrew; Smith, Jonathan M. (1998). Philosophy and Geography II: The Production of Public Space. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 240, 241. ISBN 9780847688104.

- "Engin Deniz Tanir, October 2005, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, p. 70" (PDF). Etd.lib.metu.edu.tr. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Savić, Milan (1981). "Istoriya na bŭlgarskiy narod".

- Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. 2 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) para. 6. "According to the information about the language spoken among the Muslims in the cities, we can see of which nationality they were. So, the Muslim population of Niš and Pirot consisted mostly of Turks; para. 11. "The Turks have been mostly city dwellers. It is certain, however, that part of them was of Albanian origin, because of the well-known fact that the Albanians have been very easily assimilated with Turks in the cities."; para. 23, 30, 49.

- Geniş, Şerife; Maynard, Kelly Lynne (2009). "Formation of a Diasporic Community: The history of migration and resettlement of Muslim Albanians in the Black Sea Region of Turkey". Middle Eastern Studies. 45 (4): 556. doi:10.1080/00263200903009619.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "that the Muslim Albanians of Nish were forced to leave in 1878, and that at that time most of these Nishan Albanians migrated south into Kosovo, although some went to Skopje in Macedonia."

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire: Facts on File library of world history. Infobase Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1438110257.

- Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire; Gabor Agoston, Bruce Alan Masters; 2009, p. 104

- Judah, Tim (2008). Kosovo: What everyone needs to know. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780199704040.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "This was the year that saw Serbia expanding southward and taking Nis. The Albanian quarter was burned and Albanians from the surrounding villages forced to flee."

- Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. 2 (2).

Before the war, there were about 8 500 Muslims in Niš. 1 168 of them were listed in the first Serbian inventory in 1879. 797 Gypsy Muslims were probably included in that number95. According to the stated data, approximately 7 332 Muslims moved out from Niš.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 465–492. doi:10.1177/0265691405054219. hdl:2440/124622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "Prior to 1878, the Serbs comprised not more than one half of the population of Nis, the largest city in the region; by 1884 the Serbian share rose to 80 per cent."

- "Chronology". Ni.rs. Archived from the original on 2013-02-18. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2012-01-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Christopher Chant. The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II (Routledge Revivals; 2013); ISBN 1134647875, p. 209.

- Elisabeth Barker et al., British Political and Military Strategy in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe in 1944, Springer (1988); ISBN 1349193798, p. 249.

- Jozo Tomasevich. War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941-1945, Volume 2, Stanford University Press (2001); ISBN 0804779244, p. 156.

- Milan Novaković (August 1, 2008). "Niškevesti.rs: Katastrofalna poplava u Nišu juna 1948. godine" (in Serbian). Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- D. Stojanović (May 7, 2015). "Novosti: Suze za 16 žrtava kasetnih bombi" (in Serbian). Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- "Otvoren Klinički centar u Nišu, došli Vučić, Brnabić..." b92.net (in Serbian). Tanjug. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "Jezero tople vode ispod Niša". Politika.rs. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1981-2010" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- "Station Nis" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Number and the floor space of housing units" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Religion, Mother tongue, and Ethnicity" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Educational attainment, literacy and computer literacy" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Ethnicity" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Radovinović, Radovan; Bertić, Ivan, eds. (1984). Atlas svijeta: Novi pogled na Zemlju (in Croatian) (3rd ed.). Zagreb: Sveučilišna naklada Liber.

- Mikavica, A. (3 September 2017). "Slobodne zone mamac za investitore". politika.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Запослени у Републици Србији, 2019. - Годишњи просек -" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Republic of Serbia. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ""Filip Moris" kupuje DIN, BAT kupuje DIV". b92.net (in Serbian). 5 August 2003. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Drustvo za Vazdusni Saobracaj A D – Aeroput (1927-1948) at europeanairlines.no

- "Istorijski Arhiv Niš". Arhivnis.co.rs. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ""Radovi na stadionu idu po planu" : Sport : Južne vesti". Juznevesti.com. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- "Narodne novine". narodne.com.

- "Južne vesti - Leskovac, Niš, Pirot, Prokuplje, Vranje - vesti iz južne Srbije". Južne vesti.

- "Super Radio". Super Radio Niš.

- Archived 10 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "City". radiocity.rs.

- Archived 2009-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "belami.rs - najnovije vesti, vesti iz Niša, vesti iz Srbije". Belle Amie.

- Banker. "TV BANKER". bankerinter.net. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

- "RTV5 - Nis -". rtv5.rs.

- "ck0M1". medianis.net. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10.

- "Televizija Kopernikus TV K::CN". tvkcn.net. Archived from the original on 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- "Niš Twinnings". Niš City Hall. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- "Twin cities of the City of Kosice". Magistrát mesta Košice, Tr. Archived from the original on 2016-01-29. Retrieved 2013-07-27.