Mudéjar art

Mudéjar art refers to a type of ornamentation and decoration used in the Iberian Christian kingdoms, primarily in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries though it continued being used as late as the 18th century. It was applied to Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance architectural styles as constructive, ornamental and decorative motifs derived from those that had been brought to or developed by Muslims in Al-Andalus.[1]

Mudéjar elements were developed in Iberia specially in the context of historicist architecture; there was a revival in the late 19th to early 20th century Spain as Neo-Mudéjar style. These motifs and techniques are also present in the art and crafts, especially Hispano-Moresque lustreware that was once widely exported across Europe from southern and eastern Spain. The term "arte mudéjar" was coined and described by the Spanish art historian José Amador de los Ríos y Serrano in his induction discourse El estilo mudéjar, en arquitectura at the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1859.

Etymology and references to people

Mudéjar was originally the term used for Moors of Al-Andalus who remained in Iberia after the Christian Reconquista but were not initially forcibly converted to Christianity or forcibly exiled. The word Mudéjar references several historical interpretations and cultural borrowings. It was a medieval Castilian borrowing of the Arabic word Mudajjan مدجن, meaning "tamed", referring to Muslims who submitted to the rule of Christian kings. The term likely originated as a taunt, as the word was usually applied to domesticated animals such as poultry.[2] The term Mudéjar also can be translated from Arabic as "one permitted to remain", which references Christians allowing Muslims to remain in Christian Iberia. Another term with the same meaning, ahl al-dajn ("people who stay on"), was used by Muslim writers, notably al-Wansharisi in his work Kitab al-Mi'yar.[2] Mudéjars in Iberia lived under a protected tributary status known as dajn which references ahl al-dajn. This protected status suggested subjugation at the hands of Christian rulers as the word dajn resembled haywanāt dājina which meant "tame animals". Their protected status was enforced by the fueros or local charters which dictated Christians laws. Muslims of other regions outside of the Iberian Peninsula disapproved of the Mudéjar subjugated status and their willingness to live with non-Muslims.[3]

Mudéjar style in architecture

In architecture, Mudéjar style does not refer to a distinct architectural style but to the application of traditional technical, ornamental and decorative elements derived from Islamic arts to Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance architectural styles in the Christian kingdoms of Iberia (now Spain and Portugal), mostly during the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, although it continued to appear in Spanish and Portuguese architecture as well as in other regions, most notably Hispanic America, in the 16th and 17th centuries.[4]

Mudejar decoration and ornamentation includes stylized calligraphy and intricate geometric and vegetal forms. The classic architectural Mudéjar elements include the horseshoe and multi-lobed arch, muqarna vaults, alfiz (molding around an arch), wooden roofing, fired bricks, glazed ceramic tiles, and ornamental stucco work.[5] Mudéjar often makes use of girih geometric strapwork decoration, as used in Middle East architecture, where Maghreb buildings tended to use vegetal arabesques. Scholars have sometimes considered the geometric forms, both girih and the complex vaultings of muqarnas, as innovative, and arabesques as retardataire, but in Al-Andalus, both geometric and vegetal forms were freely used and combined..

Iberian Peninsula

.jpg)

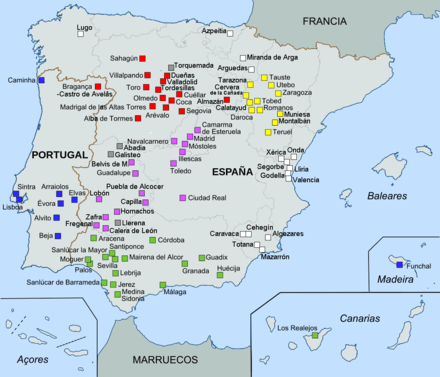

Mudéjar first developed by the Kingdom of Leon in the town of Sahagún, León as an adaptation of architectural and ornamental motifs, especially through decoration with plasterwork and brick.[6] Mudéjar then extended to the rest of the Kingdom of León, Toledo, Ávila, Segovia, etc., giving rise to what has been called brick romanesque style. Centers of Mudéjar art are found in other cities, such as Toro, Cuéllar, Arévalo and Madrigal de las Altas Torres. While international interest tends to emphasize Mudéjar masonry, including the sophisticated use of bricks and tiles, Spanish scholars also note Mudéjar carpentry, as well as the combination of the two. Several churches have slanting wooden ceilings supported by transverse arches of stone, called diaphragms.[7]

It became most highly developed in Aragon, especially in Teruel[8] but also in towns such as Zaragoza, Utebo, Tauste, Daroca, and Calatayud. During the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, many grand Mudéjar towers were built in the city of Teruel, and these unique features have survived to the present day. A particularly fine example of Mudéjar-Renaissance style is the Casa de Pilatos, built in the early 16th century at Seville. Seville includes many other examples of Mudéjar. The Alcázar of Seville is considered one of the greatest surviving examples of Mudéjar Gothic and Mudéjar Renaissance architecture.[7]

Portugal commissioned fewer and simpler examples of mudéjar elements incorporated into its architecture. The Church of Castro de Avelãs in Braganza features classic mudéjar brick work. Mudéjar also tended to be applied to the gothic Manueline style in Portugal, which was very lavish and ornate.[9] Portuguese use of mudéjar developed particularly in the 15th and 16th centuries, and structures such as the Palace of the Counts of Basto and the Royal Palace feature characteristic mudéjar wooden roofs that are also to be found in some churches in towns such as Sintra and Lisbon. Since trade was an essential part of Portugal's culture in the 16th century, imported mudéjar decorated tiles from Seville appear in churches and palaces, such as the Royal Palace of Sintra.[10]

Hispanic America

Mudéjar style decoration was carried across the world to the territories of the Spanish empire, specially in the 16th century, complementing Renaissance architecture before the emergence of Baroque.[11] The Spanish Empire in the New World incorporated this Spanish architectural tradition. Some notable examples are:

- The Church of San Miguel in Sucre, Bolivia, provides an example of Mudéjar in Hispanic America with its interior decorations and the open floor plan , geometric design can be seen through its octagonal patterned wood ceiling and the underside of the supporting arches are carved with a vegetable motif based on the arabesque. San Miguel is a direct inheritor of the Mudéjar and architecture tradition of the expansion and multiplication of an initial pattern. Around the octagonal dome, there are more wooden ceiling panels carved with the same pattern as the church's ceiling.[12]

- Other examples of Mudéjar style can be found in Coro, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Venezuela.

- The Iglesia del Espíritu Santo in Havana, Cuba.

- The Monastery of San Francisco in Lima, Peru also contains Mudéjar elements. The vaults of the central and two side naves are painted in Mudéjar style. The halls of the head cloister are inlaid with Sevillian glazed tiles, and the main altar is made entirely from carved wood.[13]

Gallery

Church of Castro de Avelãs, mudéjar romanesque, 13th and 14th centuries, Bragança, Portugal

Church of Castro de Avelãs, mudéjar romanesque, 13th and 14th centuries, Bragança, Portugal A mudéjar gothic cloister, La Iglesia de San Pedro, Teruel, Spain

A mudéjar gothic cloister, La Iglesia de San Pedro, Teruel, Spain.jpg) The Royal Alcázars of Seville, Spain, built in the 13th to the 18th centuries, with mudejar art applied to gothic, renaissance and baroque structures

The Royal Alcázars of Seville, Spain, built in the 13th to the 18th centuries, with mudejar art applied to gothic, renaissance and baroque structures Gallery of Dames, Royal Palace of Évora, 16th century, mudéjar manueline, Portugal

Gallery of Dames, Royal Palace of Évora, 16th century, mudéjar manueline, Portugal

Mudéjar style in other arts

Decorative arts

The dominant geometrical design emerged conspicuously in the crafts: elaborate tilework, brickwork, wood carving, plasterwork, ceramics, and ornamental metals. Objects, as well as ceilings and walls, were often decorated with intensely complicated designs, as Mudéjar artists were not only interested in relaying wonder, but also continued the practice of horror vacui, or a fear of empty spaces. Thus, many aspects of oriental art were packed with intricate and beautiful patterns and imagery. Many decorative arts were applied to architecture, such as the tiling and ceramic work, as well as carving practices.[14]

To enliven the surfaces of wall and floor, Mudéjar style developed complicated tiling patterns. The motifs on tile work are often abstract, leaning more on vegetal designs and straying from figural images (which is common in Islamic work). The colors of tile work of the Mudéjar period are much brighter and more vibrant than other European styles. The production process was also unique: the tile was fired before it was cut into smaller, more manageable pieces. This approach meant that the tiles and glaze work shrank less in the firing process, and retained their designs more clearly. This allowed the tiles to be laid closer together with less grout, making the compositions more intricate and cohesive.[14]

Mudéjar ornamentation is also seen in wood, ivory, metalwork, and ceramics.[15] Ceramics have long been a popular art form in Islamic work. Mudéjar style ceramics built upon techniques developed in the early centuries of Islamic art. Pottery centers all over Spain - e.g. Paterna, Toledo, Seville - focused on making a range of objects, from bowls and plates to candlesticks and turrets, etc. Artists typically worked in three “styles:” green-purple ware (manganese green), (cobalt) blue ware, and gold ware (luster earthenware). In terms of color, tin glazes were added to waterproof the ceramics and also to create gloss, hence the reference to Islamic ceramics as ‘lusterware.’ This technique was carried on from the Nasrid period. Typically, artisans would apply a layer of opaque white glaze before the colors. On top of the white, cobalt blue, green copper, and purple manganese oxides were used to make vibrant, traditional Islamic earthenware colors. Similarly in tile and stucco work, ceramic motifs included vegetal patterns, in addition to figurative motifs, calligraphy, and geometric patterns and images. There are also Christian influences in the imagery, such as boats, fern leaves, hearts, castles, etc.[16]

Literature

Following the return to Christian rule, Muslims in Castile, Aragon and Catalonia gave up the Andalusi Arabic dialect in favor of Castilian, Aragonese and Catalan. Mudéjar texts were then written in Castilian and Aragonese, but with Arabic letters.[17] Most of this literature consisted of religious essays, poems, and epic, imaginary narratives. Often, popular texts were translated into this Castilian-Arabic hybrid.[15]

Revivals of Mudéjar style

As mentioned, Mudéjar has had modern revivals, such as neo-mudéjar, that appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It has been combined with modern techniques and materials, including cast iron and glass, with traditional arches, tiling, and brickwork.[18]

Some Spanish architectural firms have turned their attention to building projects in the modern Arabic-speaking world, specifically Morocco, Algeria, and the Persian Gulf region, where Mudéjar influences are commissioned as a preferred style of housing. Mudéjar characteristics continue to act as a foundation for modernizing styles. Muslim architects are also currently making great strides in terms of modern architecture, reflecting the technical and engineering feats, as well as aesthetic expertise, reminiscent of the Mudéjar styles.[19].

.jpg)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mudéjar art. |

- Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon, an UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Neo-Mudéjar architecture

- List of missing landmarks in Spain

- Hispano-Moresque ware

- Mozarab

- Artesonado

References

- López Guzmán, Rafael. Arquitectura mudéjar. Cátedra. ISBN 84-376-1801-0.

- Harvey 1992, p. 4.

- MacKay, Angus (1977). Spain in the Middle Ages : From Frontier to Empire, 1000-1500. St. Martin's Press.

- Harvey, L. P. (1 November 1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reputation garden guide : flower seeds, garden seeds, garden bulbs, grass seeds /. Duluth, Minnesota: Duluth Floral Co. 1930. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.147501.

- "Arquitectura Mudéjar" (in Spanish). Arteguias. September 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Historia del Arte - Arte del Renacimiento - Arte mudéjar - Región de Murcia Digital". www.regmurcia.com. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- "Mudejar Architecture of Aragon". World Heritage Site. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Manueline | architectural style". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Makrickas, Augustas. "Islamic influence on western Architecture". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - CUÉLLAR, IGNACIO HENARES; GUZMÁN, RAFAEL LÓPEZ; Suderman, Michelle; ALFARO, ALFONSO; Fox, Lorna Scott; LAHRECH, OUMAMA AOUAD; Shtromberg, Elena; SÁNCHEZ, ALBERTO RUY; ZAHAR, LEÓN R. (2001). "MUDEJAR: VARIATIONS". Artes de México (55): 81–96. ISSN 0300-4953. JSTOR 24314027.

- Sheren, Ila Nicole (2011-06-01). "Transcultured Architecture: Mudéjar's Epic Journey Reinterpreted". Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture. 1: 137–151. doi:10.5195/contemp.2011.5. ISSN 2153-5914.

- "Basilica and Convent of San Francisco, Lima", Wikipedia, 2018-09-12, retrieved 2019-03-09

- Sweetman, John; Gardner, A. R. (2003). Moorish style. Oxford Art Online. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t059437.

- "Mudejar | Spanish Muslim community". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "La Cerámica Mudéjar". www.arteguias.com. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- "Aljamiado | David A. Wacks". davidwacks.uoregon.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Time out Madrid (8th ed.). London: Time Out. 2010. ISBN 9781846701207. OCLC 655671274.

- Gonzalez, Elena. “Spanish Architecture in the Arab World .” Andalusi and Mudejar Art in Its International Scope: Legacy and Modernity, 9 Sept. 2015, pp. 197–211.

Bibliography

- ARTEHISTORIA, director. El Arte Mudejar . YouTube, YouTube, 17 June 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLuE7w1Zszo.

- Boswell, John (1978). Royal Treasure: Muslim Communities Under the Crown of Aragon in the Fourteenth Century. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02090-2

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Manueline | architectural style". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Mudejar.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 20 July 1998, www.britannica.com/topic/Mudejar.

- Encyclopedia. "Art in Spain and Portugal | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Garma, David de la. “Mudejar Ceramics .” Arte Celta (ARTEGUIAS), 2012, www.arteguias.com/ceramica-mudejar.htm.

- Gonzalez, Elena. “Spanish Architecture in the Arab World .” Andalusi and Mudejar Art in Its International Scope: Legacy and Modernity, 9 Sept. 2015, pp. 197–211.

- Harvey, L. P. (1 November 1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, L. P. (16 May 2005). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31963-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, Georgiana Goddard. Mudejar. Longmans Ed, 1927.

- Linehan, P. (Ed.), Nelson, J. (Ed.), Costambeys, M. (Ed.). (2018). The Medieval World. London:Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315102511

- Makrickas, Augustas. “Islamic Influence on Western Architecture.” Academia.edu, 2013, www.academia.edu/5789655/Islamic_influence_on_western_Architecture.

- Menocal, Maria Rosa (2002). "Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain". Little, Brown, & Co. ISBN 0-316-16871-8

- Rubenstein, Richard (2003). "Aristotle's Children: How Christians, Muslims, and Jews Rediscovered Ancient Wisdom and Illuminated the Middle Ages." Harcourt Books. ISBN 0-15-603009-8

- “Scattering Seeds from the Garden of Allah.” Teposcolula Retablo, 2000, interamericaninstitute.org/work_in_progress.htm.

- Time Out. “Architecture.” TimeOut Madrid, Time Out Guides, 2010, pp. 32–34.

- Voigt. “Tile Style.” Moorish Tile History, 1 Jan. 1970, letstalktile.blogspot.com/2011/01/moorish-tile-history.html.

- Wacks, David A. Cultural Exchange in the Literatures and Languages of Medieval Iberia. 30 Oct. 2013, davidwacks.uoregon.edu/tag/aljamiado/.

.jpeg)