Amos Tversky

Amos Nathan Tversky (Hebrew: עמוס טברסקי; March 16, 1937 – June 2, 1996) was a cognitive and mathematical psychologist, a student of cognitive science, a collaborator of Daniel Kahneman, and a key figure in the discovery of systematic human cognitive bias and handling of risk.

Amos Tversky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Amos Nathan Tversky March 16, 1937 Haifa, British Mandate of Palestine (now in Israel) |

| Died | June 2, 1996 (aged 59) Stanford, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Alma mater | University of Michigan Hebrew University |

| Known for | Prospect theory Heuristics and biases |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | MacArthur Award Grawemeyer Award in Psychology (2003) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cognitive psychology, Behavioral economics |

| Institutions | Hebrew University Stanford University |

| Doctoral students | Maya Bar-Hillel |

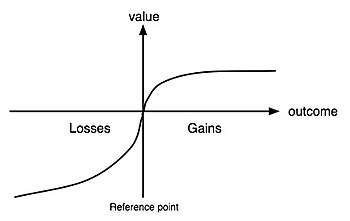

Much of his early work concerned the foundations of measurement. He was co-author of a three-volume treatise, Foundations of Measurement (recently reprinted). His early work with Kahneman focused on the psychology of prediction and probability judgment; later they worked together to develop prospect theory, which aims to explain irrational human economic choices and is considered one of the seminal works of behavioral economics. Six years after Tversky's death, Kahneman received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for the work he did in collaboration with Amos Tversky.[1] (The prize is not awarded posthumously.) Kahneman told The New York Times in an interview soon after receiving the honor: "I feel it is a joint prize. We were twinned for more than a decade."[2] Tversky also collaborated with many leading researchers including Thomas Gilovich, Itamar Simonson, Paul Slovic and Richard Thaler. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Tversky as the 93rd most cited psychologist of the 20th century, tied with Edwin Boring, John Dewey, and Wilhelm Wundt.[3]

Biography

Tversky was born in Haifa, British Palestine (now Israel), as son of the Polish-born veterinarian Yosef Tversky and Lithuanian Jewish Jenia Tversky (née Ginzburg), a social worker who later became member of parliament for the Mapai (worker's party).[4] Tversky had one sister, Ruth, thirteen years his senior. In high school, Tversky took classes from literary critic Baruch Kurzweil, and befriended classmate Dahlia Ravikovich, who would become an award-winning poet. During this time, he was also a member and leader in Nahal, a youth movement meant to combine farming and military service.[5]

Tversky served with distinction in the Israel Defense Forces as a paratrooper, rising to the rank of captain and being decorated for bravery.[4] He parachuted in combat zones during the Suez Crisis in 1956, commanded an infantry unit during the Six-Day War in 1967, and served in a psychology field unit during the Yom Kippur War in 1973.[5]

In 1963, Tversky married American psychologist Barbara Gans, now a professor in the human development department at Teachers College, Columbia University.[5] They had three children together.

Tversky received his bachelor's degree from Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel in 1961, and his doctorate from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in 1965. He later taught at Hebrew University before joining the faculty of Stanford University in 1978, where he spent the rest of his career. In 1980 he became a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[5][6] In 1984 he was a recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship, and in 1985 he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences.[7] Tversky, co-recipient with Daniel Kahneman, earned the 2003 University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Psychology.[8] He died of a metastatic melanoma in 1996.[9] He was a Jewish atheist.[10]

Career

Work with Daniel Kahneman

Amos Tversky's most influential work was done with his longtime collaborator, Daniel Kahneman, in a partnership that began in the late 1960s. Their work explored the biases and failures in rationality continually exhibited in human decision-making.[5] Starting with their first paper together, "Belief in the Law of Small Numbers", Kahneman and Tversky laid out eleven "cognitive illusions" that affect human judgment, frequently using small-scale empirical experiments that demonstrate how subjects make irrational decisions under uncertain conditions. This work was highly influential in the field of economics, which had largely presumed rationality of all actors.[11]

Comparative ignorance

Tversky and Fox (1995)[12] addressed ambiguity aversion, the idea that people do not like ambiguous gambles or choices with ambiguity, with the comparative ignorance framework. Their idea was that people are only ambiguity averse when their attention is specifically brought to the ambiguity by comparing an ambiguous option to an unambiguous option. For instance, people are willing to bet more on choosing a correct colored ball from an urn containing equal proportions of black and red balls than an urn with unknown proportions of balls when evaluating both of these urns at the same time. However, when evaluating them separately, people are willing to bet approximately the same amount on either urn. Thus, when it is possible to compare the ambiguous gamble to an unambiguous gamble people are averse — but not when one is ignorant of this comparison.

Notable contributions

- foundations of measurement

- anchoring and adjustment

- availability heuristic

- base rate fallacy

- conjunction fallacy

- framing

- behavioral finance

- clustering illusion

- loss aversion

- prospect theory

- cumulative prospect theory

- representativeness heuristic

- Tversky index

- support theory

- contrast model

In popular culture

Tversky intelligence test

As recounted by Malcolm Gladwell in 2013's David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, Tversky's peers thought so highly of him that they devised a tongue-in-cheek one-part test for measuring intelligence. As related to Gladwell by psychologist Adam Alter, the Tversky intelligence test was "The faster you realized Tversky was smarter than you, the smarter you were."[13]

The Undoing Project

Michael Lewis's book The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds, released on December 16, 2016, is about Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, and is the "story of their lives and work together".[14]

References

- Altman, Daniel (10 October 2002). "A Nobel That Bridges Economics and Psychology". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Goode, Erica (5 November 2002). "A Conversation with Daniel Kahneman; On Profit, Loss and the Mysteries of the Mind". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Haggbloom, Steven J.; Warnick, Renee; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; et al. (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139.

- A Psychologist Who Shed Light on Our Irrationality Is Born Haaretz, 16 March 2016

- Lewis, Michael (2017). The Undoing Project. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-35610-6.

- http://www.amacad.org/publications/BookofMembers/ChapterT.pdf

- "National Academy of Sciences".

- "2002- Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky". Archived from the original on 2015-07-23.

- Freeman, Karen (6 June 1996). "Amos Tversky, Expert on Decision Making, Is Dead at 59". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Engber, Daniel. “How a Pioneer in the Science of Mistakes Ended Up Mistaken.” Slate Magazine, 21 December 2016. "It’s a portrait of besotted opposites: Both Kahneman and Tversky were brilliant scientists, and atheist Israeli Jews...

- "Amos Tversky, leading decision researcher, dies at 59". Stanford University News Service. 1996-06-05. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- Fox, Craig R.; Amos Tversky (1995). "Ambiguity Aversion and Comparative Ignorance". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 110 (3): 585–603. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.8835. doi:10.2307/2946693. JSTOR 2946693.

- Malcolm Gladwell, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, 2013, page 103

- Engber, Daniel (21 December 2016). "The Irony Effect". Slate. Retrieved 26 January 2017.