Morehouse College

Morehouse College is a private historically black men's college in Atlanta, Georgia. Anchored by its main campus of 61 acres (25 ha) near downtown Atlanta, the college has a variety of residential dorms and academic buildings east of Ashview Heights. Along with Clark Atlanta University, Spelman College, and the Morehouse School of Medicine, the college is a member of the Atlanta University Center consortium. Founded by William Jefferson White in 1867 in response to the liberation of enslaved African-Americans following the American Civil War, Morehouse adopted a seminary university model and stressed religious instruction, in the Baptist tradition. Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, the college experienced rapid albeit financially unstable institutional growth by establishing a liberal arts curriculum. The three-decade tenure of Benjamin Mays during the mid-20th century led to strengthened finances, an enrollment boom, and increased academic competitiveness. The college has played a key role in the development of the civil rights movement and racial equality in the United States.[7][8]

| |

Former names | Atlanta Baptist Seminary Atlanta Baptist College |

|---|---|

| Motto | Latin: "Et Facta Est Lux" |

Motto in English | And there was light[1] |

| Type | Private Liberal Arts Men's College HBCU |

| Established | 1867 |

Academic affiliations | NAICU CIC Annapolis Group ORAU ACS Oberlin Group |

| Endowment | $145.1 million (2018)[2] |

| President | David A. Thomas[3] |

| Students | 2,132 (Fall 2018) |

| Location | , , |

| Campus | 61 acres, urban[4] |

| Colors | Maroon, white[5] |

| Nickname | Maroon Tigers[6] |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division II SIAC[6] |

| Mascot | The Maroon Tiger |

| Website | morehouse |

| |

As the largest men's liberal arts college in the U.S.,[9] Morehouse is one of two historically black colleges in the country to produce Rhodes Scholars, and is the alma mater of many African-American civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond, and Donn Clendenon. Among Morehouse alumni – traditionally known as "Morehouse Men" – the college has graduated numerous "African American firsts" in local, state and federal government as well as in science, academia, business, and entertainment.[10][11]

History

Establishment

Just two years after the American Civil War, the Augusta Institute was founded by the William Jefferson White, an Atlanta Baptist minister and cabinetmaker (William Jefferson White's half brother James E. Tate, was one of the founders of Atlanta University, now known as Clark Atlanta University), with the support of the Rev. Richard C. Coulter, a former slave from Atlanta, Georgia, and the Rev. Edmund Turney, organizer of the National Theological Institute for educating freedmen in Washington, D.C.[12] The institution was founded to educate African American men in theology and education and was located in Springfield Baptist Church (Augusta, Georgia), the oldest independent black church in the United States. The institution moved from Augusta, Georgia, to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1879. The school received sponsorship from the American Baptist Home Mission Society, an organization that helped establish several historically black colleges.[12][13] The Institute's first president was Rev. Joseph T. Robert (1871–1884) (father of Brigadier General Henry Martyn Robert, author of Robert's Rules of Order). An anti-slavery Baptist minister from South Carolina and 1828 graduate of Brown University, Robert raised funds, taught the classes, and stabilized the institution.

| 1867 | Augusta Institute established[12] |

| 1879 | Institute moved to Atlanta and name changed to Atlanta Baptist Seminary[12] |

| 1885 | The seminary moved to its present location[12] |

| 1897 | The school was renamed Atlanta Baptist College[12] |

| 1913 | School renamed to Morehouse College[12] |

| 1929 | Morehouse entered into a cooperative agreement with Clark College and Spelman College (later expanded to form the Atlanta University Center)[12] |

| 1975 | The Morehouse School of Medicine established |

| 1981 | The Morehouse School of Medicine became independent from Morehouse College |

Early years

In 1879, the institute moved to Atlanta and changed its name to the Atlanta Baptist Seminary.[12] It later acquired a 4-acre (1.6 ha) campus in downtown Atlanta. In 1885, Samuel T. Graves became the second president. That year the seminary moved to its present location, on land donated by prominent Baptist and industrialist, John D. Rockefeller. In 1890, George Sale became the seminary's third president.

In 1906 John Hope became the first African-American president and led the institution's growth in enrollment and academic stature.[12] He envisioned an academically rigorous college that would be the antithesis to Booker T. Washington's view of agricultural and trade-focused education for African-Americans. In 1913, the college was renamed Morehouse College, in honor of Henry L. Morehouse, corresponding secretary of the American Baptist Home Mission Society (who had long organized Rockefeller and the Society's support for the College).[12][13] Morehouse entered into a cooperative agreement with Clark College and Spelman College in 1929 and later expanded the association to form the Atlanta University Center.[12]

Samuel H. Archer became the fifth president of the college in 1931 and selected the school colors, maroon and white, to reflect his own alma mater, Colgate University. Benjamin Mays became president in 1940.[12] Mays, who would be a mentor to Martin Luther King Jr., presided over the growth in international enrollment and reputation. During the 1960s, Morehouse students were actively involved in the civil rights movement in Atlanta.[12] Mays' speeches were instrumental in shaping the personal development of Morehouse students during his tenure.

In 1967, Hugh M. Gloster became the seventh president. The following year, the college's Phi Beta Kappa Honors Society was founded. In 1975, Gloster established the Morehouse School of Medicine, which became independent from Morehouse College in 1981. Gloster also established a dual-degree program in engineering with the Georgia Institute of Technology, University of Michigan and Boston University.[14]

Modern history

Leroy Keith Jr., was named president in 1987. In 1995, alumnus Walter E. Massey, became Morehouse's ninth president. His successor, Robert Michael Franklin Jr. was the tenth president of the College. In November 2012, John Silvanus Wilson, an alumnus of Morehouse College, was announced as the institution's 11th president.[15] In January 2018, David A. Thomas took office as the college's 12th president.[16]

In 2007, Morehouse graduated 540 men, one of the largest classes in its history.[17] On May 16, 2008, Joshua Packwood became the first white valedictorian to graduate in the school's 141-year history.[18][19] In August 2008, Morehouse welcomed a total of 920 new students (770 freshmen and 150 transfer students) to its campus, one of the largest entering classes in the history of the school.[20]

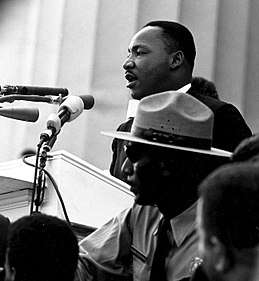

Morehouse celebrated several historic milestones in 2013. One century prior, in 1913, Atlanta Baptist College was renamed Morehouse College after Henry Lyman Morehouse, corresponding secretary for the American Baptist Home Mission Society. 2013 was also the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, when Morehouse graduate the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., class of 1948, delivered his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech in Washington, D.C. The year also marked the 50th anniversary of King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail." The College also celebrated the 25th anniversary of the "A Candle in the Dark" Gala, which honors some of the world's leaders and raises scholarship funds for Morehouse students.

In May 2013, President Barack Obama became the first sitting president in three-quarters of a century to deliver a commencement address in Georgia when he took part in Morehouse College's 129th Commencement ceremony. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had given a summer commencement address at the University of Georgia in 1938. President Obama received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Morehouse.[21]

In April 2019, Morehouse announced that they will begin admitting transgender men for the first time in the year 2020.[22] In May 2019, Robert F. Smith who received an honorary degree at Morehouse College's 135th commencement ceremony, promised to pay the educational loan debt for every spring 2019 graduate which totaled about $34 million.[23][24] Smith's gift is the second largest single donation from a living donor to a HBCU in history.[25]

In June 2020, Reed Hastings and his wife Patty Quillin donated $40 million to Morehouse College to be used as scholarship funds for students enrolled at Morehouse. Their single donation is the largest in Morehouse and HBCU history.[26] In July 2020, Morehouse received a $20 million donation from MacKenzie Scott.[27]

Administration and organization

Morehouse's governing body is its Board of Trustees. The Morehouse Board of Trustees has 37 members, including three student trustees and three faculty trustees. As of December 2014, five of the six executive board members and seven of the 31 general trustees are Morehouse alumni.

The president of the college is the senior executive officer, appointed officially by the Board of Trustees. The current President of Morehouse is David A. Thomas. The President's Office has several leaders within its Executive Leadership Team including Academic Affairs (headed by the Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs), General Counsel, Business and Finance, Marketing and Communications, Information Technology, Institutional Advancement, External Relations, and Student Affairs.

Morehouse's majors and programs are divided into three divisions: the Division of Business Administration & Economics; the Division of Humanities and Social Sciences, and the Division of Science & Mathematics. Each division is headed by a dean.

Morehouse's students are represented by two main bodies. The Morehouse Student Government Association is an executive board with 13 members who are elected annually. There is also the Campus Alliance for Student Activities (CASA), a 17-member board responsible for co-curricular planning across campus.

Morehouse is also a member of the Atlanta University Center, a consortium of the historically black colleges and universities Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, the Interdenominational Theological Center, and Morehouse School of Medicine. The AUC campuses are co-located in the city of Atlanta, which provides an opportunity for cross-registration and social intermingling amongst the students there, particularly the undergraduate population.

Campus

Morehouse is located on 61 acres (25 ha) campus near downtown Atlanta.[4] The campus operates recycling programs for paper, toner and ink jet printer cartridges to promote environmental responsibility.[28]

Buildings

- Archer Hall, named after the fifth president of Morehouse College, Samuel H. Archer, holds the College's recreational facilities such as its gymnasium, swimming pool, and game room. The gymnasium seats 1,000 people and was used by the College's basketball team before Franklin Forbes Arena was built.

- B. T. Harvey Stadium/Edwin Moses Track is a 9,000-seat stadium built in 1983. The track is named after the only alumnus to win an Olympic gold medal. At the time of the stadium's completion, it was the largest on-campus stadium at any private HBCU in the nation [29]

- Brawley Hall, named after Benjamin Griffith Brawley, houses the college's History, English, Language, and Art departments.

- Brazeal Hall is a dormitory built in 1991. It housed athletes during the time of the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Brazeal Hall originally housed upperclassmen, though it currently serves as a freshmen dorm.

- Ray Charles Performing Arts Center and Aretha Robinson Music Academic Building is a 76,000-square-foot (7,100 m2) facility dedicated on September 29, 2010. The Emma & Joe Adams concert hall is named after Ray Charles' longtime manager and his wife. Joe Adams was president of the Ray Charles Foundation and played a significant fundraising role in the construction of the center., [30]

- Chivers Hall/Lane Hall is the cafeteria of the college and has been featured in many movies. It seats 600 people and is attached to Mays Hall. The Sadie Mays lounge, named for the wife of Mays, connects Mays Hall and Chivers Hall.

- Dansby Hall houses the school's Physics, Psychology, and Mathematics departments.

- Douglass Hall (also known as LRC (Learning Resource Center)), named after Frederick Douglass was originally built as the school's student center but today serves as an academic readiness center, which features study spaces, conference rooms, and a computing lab. Most of the college's tutoring and academic support programming takes place here.

- DuBois Hall is a freshman dorm erected in 1973, named after philosopher W. E. B. Du Bois.

- Franklin L. Forbes Arena is a 5,700 capacity seat arena, built for the 1996 Olympic Games. It is now the main gymnasium for the college's basketball team and holds many events year-round. In 2018, for the first time in program history, Morehouse hosted the 2018 NCAA Division II Men's Basketball Tournament's South Region Championship and the 2018 McDonald's All American Dunk Contest in Forbes Arena. The arena has hosted many celebrities and politicians, including President Barrack Obama and presidential hopefuls Stacey Abrams, Bernie Sanders, and Joe Biden.

- Graves Hall, named after the second president of Morehouse College, Samuel T. Graves, is home to the Howard Thurman Honors Program and Bonner Scholars. When constructed in the 1880s, it was the tallest building in Atlanta. When the college relocated to the West End area, student housing, classrooms, and administration offices were all contained within the building.

- Hope Hall was named after John Hope, the first African American president (fourth president) of Morehouse College. When erected, it was known as the Science Building, then later the Biology Building. Through the years, the building became too small for classroom use and now holds laboratories for departments that are in other buildings. Hope Hall includes the offices of the Public Health Sciences Institute.

- Hubert Hall is a freshman dorm named after Charles D. Hubert, who was an acting president from 1938 to 1940.

- Kilgore Campus Center houses administrative offices, as well as several seminar rooms and lounges. A separate area of the building serves as a dormitory. Archer Hall, B. T. Harvey Stadium, and the exterior of Graves Hall are featured in the Spike Lee film School Daze.

- Living Learning Center (LLC) was formerly known as Thurman Hall. It is one of the school's freshman dorms.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. International Chapel/Gloster Hall was built in 1978 as the new auditorium and administration building for Morehouse College, replacing Sale and Harkness halls (Harkness is now a Clark Atlanta University structure). It is home to the Gandhi–King–Ikeda Reconciliation Institute.

- Mays Hall was named after the sixth president of Morehouse College, Benjamin Mays. It houses dorm rooms and is the headquarters for residence life for the college.

- Merrill Hall, named after Charles E. Merrill Jr., a chairman of the College's Board of Trustees, became the chemistry building. The 2000s (decade) saw Merrill Hall undergo a renovation that doubled its size. Its new corridor is called John Hopps Technology Tower', which houses the Computer Science department as well as the office of Information Technology Services.

- Nabrit–Mapp–McBay Hall was erected in 1987. The building is also known as Bio-Chem' from a plaque at the corridor stating that the building was built to house the Biology and Chemistry classrooms. It now holds the Biology department. It was named for distinguished science professors Samuel M. Nabrit, Frederick Mapp, and Henry McBay.

- Otis Moss Jr. Residential Suites are apartment, studio, and suite dwellings built in 2003. The Suites were renamed in spring 2006, after Otis Moss Jr. (class of 1956), former chair of Morehouse's Board of Trustees.

- Perdue Hall is a residences hall built around the time of the 1996 Summer Olympics. It housed athletes during the 1996 Olympic events.

- Robert Hall, named after Joseph T. Robert, the first president of the College, was erected to be the College's first residence hall. When built, there was a cafeteria in its basement. Today the basement houses a post office.

- Sale Hall, named after the third president, was built to contain classrooms. Today, it is the department building for religion and philosophy courses. On the second floor, a small auditorium, called the Chapel of the Inward Journey', was used for religious and commencement proceedings. Today, the chapel is used for recitals, pageants, and student government association election debates.

Shirley A. Massey Executive Conference Center is named after the first lady of the ninth president of the college. It houses several large conference rooms and the Bank of America Auditorium. The building has hosted human rights film festivals, moving screenings, and panel discussions featuring international figures.

- Walter E. Massey Leadership Center houses the Business Administration and Economics departments, the Bonner Office of Community Service as well as other offices. It also has a 500-seat auditorium and an executive conference center. The building was completed in 2005 and is named after Walter E. Massey (ninth president).

- Wheeler Hall is a building used primarily by the Political Science and Sociology departments.

- White Hall is a freshman residence hall, named after the College's founder.

Monuments

A bronze statue of Martin Luther King Jr. stands at the eastern portion of the main entrance plaza of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel. Inscribed in the base of the statue are the words of King.

An obelisk named in honor of Howard Thurman stands at the western end of the main entrance plaza of King Chapel. The base of the Thurman Obelisk contains the remains of Thurman and his wife. The obelisk also houses a carillon.

The grave sites of two presidents of Morehouse College are located on campus:

- A statue of Benjamin Mays stands atop a marble monument situated in front of Graves Hall. This monument marks the graves of President Mays and his wife, Sadie Gray Mays. Behind the graves are memoirs and a time capsule set to be opened in May 2095.

- Hugh Morris Gloster, seventh president of Morehouse College and founder of Morehouse School of Medicine, is buried in the eastern lawn of the College's main administration building bearing his name.

Academics

Morehouse College is accredited by the Commission and Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees. Students may choose from over 26 majors and may participate in the Morehouse College Honors Program which is a four-year comprehensive program providing special learning opportunities for select students of outstanding intellectual ability, high motivation, and broad interests.

Morehouse College has received considerable attention as an outstanding national leader among liberal arts colleges from an array of media and ranking agencies. CNN quoted Sterling Hudson, the former dean of admissions, as saying, "Like every other college, we're interested in diversity. So, if a white student becomes interested in Morehouse - of course we are going to treat him like any other student."[31]

Morehouse sponsors "Project Identity", a federally funded program to stimulate interest among high school students to attend college. Project Identity conducts Saturday and summer programs for high school students to give minority students exposure to college academic life.[32]

High School juniors in the Atlanta area may gain admission into Morehouse's Joint Enrollment program which allows a high school senior to enroll in Morehouse classes and earn credits toward both a Morehouse degree as well as a high school diploma.[33]

Historically, Morehouse has conferred more bachelor's degrees on black men than any other institution in the nation.[34]

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[35] | 645 |

| THE/WSJ[36] | 401–500 |

| Liberal arts colleges | |

| U.S. News & World Report[37] | 154 |

| Washington Monthly[38] | 199 |

- For 2020, U.S. News & World Report ranked Morehouse tied for 154th overall, and tied at 12th for "Social Mobility", tied for 21st "Most Innovative", and tied for 25th "Best Undergraduate Teaching" among liberal arts colleges in the U.S.; additionally, it ranked Morehouse tied for 4th among "Historically Black Colleges and Universities.[39]

- In 2019, The Alumni Factor ranked Morehouse among the best 50 colleges in the nation.[40]

- As of 2018, Morehouse is the No. 1 institution of all types for producing the most black male Rhodes Scholars.[41][42][43]

- As of 2016, Morehouse is the No. 1 baccalaureate-origin institution of black male doctorate recipients.[42][44]

- In 2015, TrendTopper MediaBuzz College Guide ranked Morehouse as the No. 1 HBCU with the best brand.[45]

- In 2015, Forbes ranked Morehouse No. 5 for "Most Entrepreneurial College"[46]

- A 2008 National Science Foundation study found that of over 3,000 colleges and universities in the U.S., Morehouse College was the fifth biggest producer of African Americans who eventually earned PhDs in the STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics).[47]

- Morehouse is the No.1 feeder school for black men entering Harvard Law and Business Schools.[48]

Library and collections

Morehouse College, along with other members of the Atlanta University Center, share the Robert W. Woodruff Library.[49]

Morehouse College is home to a 10,000-piece collection of original documents written by Martin Luther King Jr. (referred to as the King Collection). The set was valued by the Library of Congress as being worth between $28 to $30 million and was originally scheduled by his family to be auctioned off to the general public in 2006, but private donors in Atlanta intervened and offered a pre-auction bid at $32 million. On June 29, it was announced by Atlanta mayor Shirley Franklin, a key catalyst in the buyout, that a new civil rights museum would be built in the city to make the documents available for research, public access and exhibits. Coca-Cola donated a land parcel valued at $10 million in order to assist with the development of the project. The collection includes King's 1964 Nobel Prize acceptance speech.[50][51][52][53]

Student life

New Student Orientation

Morehouse's New Student Orientation (NSO) is an eight-day experience that culminates with new students ceremoniously initiated as Men of Morehouse. New students learn about the legacy of the college, traditions, academic divisions, the brotherhood, and the "Morehouse Mystique". These components complement academic success strategies designed to help students successfully matriculate to Morehouse Men (graduates). NSO is led by student orientation leaders, staff and alumni; all new students are placed on midnight curfew during NSO.[54][55]

Residence halls

Morehouse has 12 residence halls on campus.[56] Approximately 60% of Morehouse students live on campus.[57] Six residence halls are for first-year students only and five for upperclassmen. It is a tradition for students living in first-year only residence halls to compete in various friendly competitions (i.e. stroll-offs, chant-offs, pranks, fundraising, etc.) during the academic school year. Seniors are the only group automatically allowed to live off campus, non-seniors must get approval by the college.[58]

Regulation of campus attire

In October 2009, Morehouse College initiated a campus wide attire policy that prohibits students from wearing women's clothes, jewelry on their teeth, pajamas as classroom attire, tight fitting caps or bandannas on their heads, or pants which hang below the waist at official college-sponsored events. This dress code is part of the Five Wells which holds that "Morehouse Men are Renaissance Men with a social conscience and global perspective who are Well-Read, Well-Spoken, Well-Traveled, Well-Dressed and Well-Balanced."[59] William Bynum, vice president for Student Services was quoted by CNN as saying, "We are talking about five students who are living a gay lifestyle that is leading them to dress [in] a way we do not expect in Morehouse men."[60] These remarks and the attire policy itself have been the source of great controversy both on and off the campus. President Franklin personally sent out an email to the schools' alumni, clarifying that the university's attire policy is not intended as an affront to effeminate or gay men.[61][62]

Activities

Morehouse College offers organized and informal co-curricular activities including over 80 student organizations, varsity, club, and intramural sports, and student publications.[63] Morehouse is a NCAA Division II school and competes in numerous sports, including football, baseball, basketball, cross country, and track & field.

Morehouse Marching Band (House of Funk)

The Morehouse College Marching Band, better known as the House of Funk, is known for their halftime performances which combine dance and marching with music from various genres, including rap, traditional marching band music, and pop music. They have performed at Super Bowl XXVIII, the Today Show, at Atlanta Falcons home games, and in a national commercial with Morehouse alumnus Samuel Jackson.[64] They gave the halftime show during the 2013 NCAA Men's National Championship basketball game. Affectionately known as the "House of Funk" they march alongside Spelman's Maroon Mystique Color guard (flag spinning) squad and Mahogany-N-Motion danceline.

Debate team

Morehouse's debate team was formed in 1906 and has won many accolades since its founding. In 2005, Morehouse College became a member of the American Mock Trial Association (AMTA).[65] The school is one of only four competing teams to come from a historically black college and is also the only all-male team in the AMTA. From 2006 to 2010, Morehouse consecutively won their regional championship competitions, and thus received direct trips to the AMTA national championship competitions in Iowa, Florida, and Minnesota.[66]

In 2016, Morehouse became the only HBCU, Georgia institution, and men's college chosen to host the annual U.S. Universities Debating Championship which had nearly 200 teams from across the nation participate.

In 2017, the Morehouse College Debate Team won an international first place title and a trip to Paris, France after defeating Vanderbilt University in the final round at the Lafayette Debates North American Championship in Washington D.C.[67]

Glee Club

Founded in 1911, the Morehouse College Glee Club has a long and impressive history. The Glee Club performed at Martin Luther King Jr.'s funeral, President Jimmy Carter's inauguration, Super Bowl XXVIII, and the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. The Glee Club's international performances include tours in Africa, Russia, Poland and the Caribbean. The group also appeared on the soundtrack for the movie School Daze, directed by notable Morehouse alum (c/o 1979), Spike Lee. Most recently, the Morehouse College Glee Club was invited to perform at the ABCUSA 2011 Conference in Puerto Rico. Also, the glee club studio-recorded a song for Spike Lee's "Red Hook Summer" entitled Zachary and the Scaly-Bark Tree.

The Maroon Tiger

The college's weekly student-run newspaper is 'The Maroon Tiger. Founded in 1898 as The Athenaeum, it was renamed in 1925. American poet and writer Thomas Dent was a contributor while he attended from 1948 to 1952, as was Martin Luther King Jr. The 2008–2009 staff sought to expand the newspaper into a news organization by creating Morehouse's first television news program, Tiger TV, and advancing online news coverage.[68][69]

Miss Maroon & White

Several Spelman and Clark Atlanta juniors that advance pass preliminary interviews, vie for the prestigious title of Miss Maroon & White through a formal campaign and beauty pageant process during the spring semester. Only Morehouse students can vote to determine the winner which is the contestant that best represents the ideal counterpart for a "Morehouse Man". Miss Maroon & White and her royal court (two runners-ups known as attendants) collectively serve as official Morehouse ambassadors and represents the womanly embodiment of the institution for a year.

The tradition of crowning a young woman as Miss Maroon & White began in 1936 with Miss Juanita Maxie Ponder of Spelman College winning the first crown. Miss Maroon & White is the longest active pageant title in the Atlanta University Center.[70][71]

National fraternities and honor societies

Morehouse College has chapters of several national fraternities and honor societies on campus. Three percent of students are active in Morehouse's NPHC and Non-NPHC organizations.[72]

NPHC

- Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity (Pi chapter)

- Phi Beta Sigma fraternity (Chi chapter)

- Omega Psi Phi fraternity (Psi chapter)

- Iota Phi Theta fraternity (Alpha Pi chapter)

- Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity (Alpha Rho chapter)

Non-NPHC

- The Tiger 6 – MAA'T chapter of Groove Phi Groove Social Fellowship, Inc.

Honor societies

- Phi Beta Kappa (Delta of Georgia chapter)

- Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia

- Phi Alpha Delta

- Phi Sigma Tau (Georgia Kappa Chapter)

- Kappa Kappa Psi

- Alpha Kappa Delta

- Beta Gamma Sigma

- Beta Kappa Chi

- Chi Alpha Epsilon

- Omicron Delta Epsilon (Iota of Georgia)

- Omicron Delta Kappa

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- National Society of Collegiate Scholars

Religious organizations

Campus religious organizations include the Atlanta University Center Catholic Student Coalition, King International Chapel Ministry, Martin Luther King International Chapel Assistants, King Chapel Choir, Muslim Students Association, New Life Inspirational Fellowship Church Campus Ministry, and The Outlet.[63]

Athletics

In sports, the Morehouse College Maroon Tigers are affiliated with the NCAA Division II Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SIAC). Morehouse College competes in football, baseball, basketball, cross country, tennis, track & field, volleyball, polo, and golf.

In 2019, a $1 million grant enabled Morehouse and five other SIAC institutions to sponsor an intercollegiate men's volleyball team. Collectively, the six institutions are the first HBCUs to sponsor a men's volleyball team.[73] In 2020, Morehouse became the first HBCU to establish an intercollegiate polo team as a member of the United States Polo Association.[74] In June 2020, Morehouse cancelled their football and cross country seasons, citing concerns over COVID-19.

Notable alumni

Morehouse alumni include notable African-Americans such as: Martin Luther King Jr., theologian Howard Thurman, filmmaker Spike Lee, filmmaker Robert G. Christie (a.k.a. Bobby Garcia), actor Samuel L. Jackson, civil rights leader Julian Bond, businessman and former 2012 Republican presidential candidate Herman Cain, Secretary of Homeland Security in 2013 Jeh Johnson, University president and health care executive Albert W. Dent, NFL Referee Jerome Boger, celebrity physician Corey Hébert, U.S. Congressman Sanford D. Bishop, Gang Starr rapper Guru, Four-time 400 meter hurdles world record holder and twice Olympic gold medalist Edwin Moses, U.S. District Court Judge George J. Hazel, Lloyd McNeill, Jazz flutist, USPS Kwanza Stamp designer, the first recipient of Howard University's MFA Degree, former Bank of America Chairman Walter E. Massey, the first African-American mayor of Atlanta Maynard Jackson, Major League Baseball first baseman and 1969 World Series MVP Donn Clendenon, former Secretary of Health and Human Services Louis W. Sullivan, former United States Surgeon General David Satcher, entrepreneur and award-winning technologist Paul Q. Judge, musician PJ Morton, author Jared Andre Sawyer Jr., Metro Boomin,rap producer, Sunday Best season 7 winner Geoffrey Golden, Montgomery County Alabama Circuit Court Judge Greg Griffin[75] and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) scientist that attempted to stop the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Bill Jenkins.[76]

According to Morehouse's own "About Us" page, Morehouse was the first historically black college to produce a Rhodes Scholar. The school's first Rhodes Scholar, Nima Warfield, was named in 1994, the second, Christopher Elders, in 2001.[77] A third, Oluwabusayo "Topé" Folarin, was named in 2004, the fourth, Prince Abudu, was named in 2015.[41] Morehouse has been home to eleven Fulbright Scholars. Since 1999, Morehouse has produced five Marshall Scholars, one Schwarzman Scholar, five Luce Scholars, four Watson Fellows and 2010 White House Fellow, Erich Caulfield.[78][79] Previous Watson Fellows include, Craig Marberry '81, Kenneth Flowers '83 and Lynn P. Harrison III '79.

Presidents Barack Obama[80] and Jimmy Carter hold honorary doctorates of laws from Morehouse, after giving commencement speeches.[21]

Oprah Winfrey Scholars

In 1990, Oprah Winfrey pledged to put 100 deserving young men through Morehouse. She made a donation to establish the "Oprah Winfrey Endowed Scholarship Fund". The school uses the fund to select deserving students based on academic achievement and financial need. Selected students are deemed "Oprah Scholars" or "Sons of Oprah". Their financial support covers most of the costs of their education including prior student debt.[81] Recipients must maintain their grade point average and provide additional volunteer support to the community.[82]

In 2004 Winfrey increased her donation by $5 million for a total donation of $12 million. The fund has since supported over 400 students. In 2011, several hundred Oprah Scholars surprised Winfrey by showing up at her final TV show carrying candles to thank her for her generosity. They, in turn, pledged $300,000 to help educate future Morehouse students.[83]

In 2019, Winfrey added $13 million to the scholarship program bringing her grand total donations to $25 million.[84]

Gandhi King Ikeda Awards

Lawrence Carter, Professor of Religion and Dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel at Morehouse College, founded the MLK Chapel Assistants Pre-seminarians Program. He commissioned the Gandhi Ikeda King Hassan Institute for Ethics and Reconciliation in 1999, and created the Gandhi–King–Ikeda Community Builder's Prize of the Morehouse Chapel in 2001.[85] Named after Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968), and Daisaku Ikeda (born 1928), Morehouse's MLK Chapel awards the Gandhi, King, Ikeda Community Builders Prizes[86] as well as the Gandhi King Ikeda Awards for Peace.[87] Recipients include[88]

Notes

References

- "List of HBCUs – White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities". 2007-08-16. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2008-01-03. (literal translation of Latin itself translated from Hebrew: "And light was made")

- As of June 30, 2018. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2017 to FY 2018" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2018. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- "Breaking: Morehouse College names new president".

- "USNews.com:America's Best Colleges 2008: Morehouse College: At a glance". USNews.com. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- "Morehouse College Official Colors" (PDF). Morehouse College Brand Guidelines. August 23, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- "The SIAC.com – Morehouse College". Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- Kelly, Jason (January 1, 2013). "Benjamin Mays found a voice for civil rights". The University of Chicago. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Smith, Clint (November 3, 2018). "Why Historically Black Colleges Are Enjoying a Renaissance". National Geographic Magazine. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Palmer, Robert T.; Cadet, Mykia O.; LeNiles, Kofi; Hughes, Joycelyn L. (2019-02-18). Personal Narratives of Black Educational Leaders: Pathways to Academic Success. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-58402-9.

- Goldberg, Emma (June 6, 2020). "The Class of 2020 Is Missing Out, and So Are Politicians". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Brawley, Benjamin (2009-01-01). History of Morehouse College. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60520-665-3.

- "Morehouse College". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Brawley, Benjamin (1917). History of Morehouse College. Atlanta: Morehouse College. pp. 135–141.

Benjamin Griffith Brawley.

- "Morehouse College Fact Book 2004-2008" (PDF). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- Suggs, Ernie (November 12, 2012). "Morehouse names president". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "Morehouse College | Profile". morehouse.edu. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "Morehouse Graduates Largest Class". Archived from the original on September 27, 2008.

- "White valedictorian: A first for historically black Morehouse". CNN. 2008-05-16. Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- Marcus K. Garner, "White valedictorian makes Morehouse history", 18 May 2008. Ajc.com Archived by WebCite

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-11. Retrieved 2016-02-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Remarks by the President at Morehouse College Commencement Ceremony". Transcript. Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- "All-male historically black Morehouse College will admit transgender men". The Guardian. Associated Press. April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/09/20/morehouse-billionaire-gift-smith-donates-34-million-pay-off-loans/2392458001/

- McLaughlin, Eliott C. "Morehouse College grads are surprised by a billionaire's promise to pay off their student loans". CNN. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- Harris, Adam (May 19, 2019). "What Happens When a Billionaire Swoops In to Solve the Student-Debt Crisis". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- https://www.morehouse.edu/newscenter/morehouse-college-student-success-program-receives-40-million-donation-from-philanthropists-patty-quillin-and-reed-hastings.html

- https://www.11alive.com/article/news/local/mackenzie-scott-morehouse-college-donation/85-f95add53-1480-4d08-a1cb-e98e778f4764

- "Campus Operations – Recycling Program". Morehouse College. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- 1983 Morehouse Torch (Yearbook)

- "Morehouse Cuts the Ribbon on the Ray Charles Performing Arts Center and Music Academic Building". Morehouse College. Archived from the original on 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- Dana Rosenblatt and Don Lemon (May 19, 2008). "White valedictorian: A first for historically black Morehouse". CNN. Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2010-10-11.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Project Identity". Morehouse College. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- "Freshmen Requirements". Morehouse College. Archived from the original on 2010-11-29. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- "Morehouse College". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2015-05-13. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "U.S. College Rankings 2020". Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- "Best Colleges 2020: National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "2019 Liberal Arts Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "Morehouse College Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "The Alumni Factor". www.alumnifactor.com.

- "Morehouse College Senior Selected to 2016 International Rhodes Scholar Class ‹ Morehouse College News Center". Morehouse.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- "Home – The Rhodes Scholarships" (PDF). www.rhodesscholar.org.

- "Morehouse College | House News". www.morehouse.edu. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "Morehouse College - Fact Book". Morehouse.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- http://media-newswire.com/release_1185616.html

- Chen, Liyan. "5 Morehouse College". Forbes. p. 5.

- "Role of HBCUs as Baccalaureate-Origin Institutions of Black S&E Doctorate Recipients". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "Morehouse College | Facts at a Glance". www.morehouse.edu. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "Home".

- "Atlanta Deal for King Papers Paves Way for Museum, Mayor Says". bloomberg.com. 2006-06-29. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- "The King Papers at Morehouse College". morehouse.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- "New Home for King Papers". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- "Coca-Cola giving land for museum on civil rights". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- "Morehouse College – New Student Orientation".

- Freedman, Samuel G. (21 August 2015). "Parents' Ceremony Serves Up Elements of 'Morehouse Gospel'". Nytimes.com.

- "OHRL - Residential College". ohrl.webflow.io. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2018-09-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "FAQs". Ohrl.webflow.io. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "The Soul of Morehouse and the Future of the Mystique: President's Town Hall Meeting" Archived 2013-06-01 at the Wayback Machine (Robert M. Franklin (2009)).

- Mungin, Lateef (October 17, 2009). "All-male college cracks down on cross-dressing". CNN. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- "Morehouse Responds to Dress Code Controversy". Archived from the original on November 2, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- http://blackyouthproject.com/morehouse-from-your-closet-speaks-truth/

- "America's Best Colleges 2008: Morehouse College: Campus Life". USNews.com. 2008 U.S. News & World Report, L.P. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- "Capital One Quicksilver TV Spot, 'Marching Band' Feat. Samuel L. Jackson".

- "Team Numbers". American Mock Trial Association. Archived from the original on 2007-04-02. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- "Tournament News : Des Moines Results". Perjuries.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- Chen, Celeste Headlee, Linda. "Morehouse First HBCU To Host USU Debating Championship".

- https://themaroontiger.com/about/

- http://maroontigermedia.com/tigertv/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-22. Retrieved 2016-03-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "MH Mag.Wntr04.9999" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/morehouse-college-1582/student-life

- https://theundefeated.com/features/morehouse-five-other-hbcus-to-start-mens-volleyball-programs-with-1-million-grant/

- https://atlantatribune.com/2020/02/14/morehouse-college-polo-club-is-legit-makes-hbcu-history/

- "Greg Griffin (Alabama)".

- "Bill Jenkins, Who Tried to Halt Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Dies at 73".

- "Morehouse Student Named Rhodes Scholar". Morehouse College News. 2001-12-10. Archived from the original on 2006-07-20. Retrieved 2006-06-15.

- Black Past Remembered Retrieved on 2011-02-10.

- "Black Scholars". Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "Read President Obama's Commencement Address at Morehouse College". Time. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- "Columbus Man Credits Oprah For College Education". 10tv.com. 24 May 2011.

- "Local Oprah Scholar on final show". Coastalcourier.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-04. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- "Oprah's Generosity Spurs Past Morehouse Scholarship Recipients to Pledge New Scholarship Funding". Diverseeducation.com. 27 May 2011.

- https://www.ajc.com/news/local-education/oprah-winfrey-donates-million-morehouse-college/rsxbVL8Ry1DIOC4k0boOUK/

- "Lawrence Carter | The HistoryMakers". www.thehistorymakers.com. Retrieved 2017-04-19.

- "Morehouse College – Peace Programs". www.morehouse.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-06-25. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "IIS Governor Receives Prestigious Gandhi King Ikeda Award for Peace". iis.ac.uk. The Institute of Ismaili Studies (IIS). Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "Morehouse College". www.morehouse.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-14. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

Sources

- Addie Louise Joyner Butler, The Distinctive Black College: Talladega, Tuskegee, and Morehouse (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1977).

- Leroy Davis, A Clashing of the Soul: John Hope and the Dilemma of African American Leadership and Black Higher Education in the Early Twentieth Century (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998).

- Edward A. Jones, A Candle in the Dark: A History of Morehouse College (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1967). Moss Kendrix, P.R icon