Maudgalyayana

Maudgalyāyana (Pali: Moggallāna), also known as Mahāmaudgalyāyana or by his birth name Kolita, was one of the Buddha's closest disciples. Described as a contemporary of disciples such as Subhuti, Śāriputra (Pali: Sāriputta), and Mahākāśyapa (Pali: Mahākassapa), he is considered the second of the Buddha's two foremost male disciples, together with Śāriputra. Traditional accounts relate that Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra become spiritual wanderers in their youth. After having searched for spiritual truth for a while, they come into contact with the Buddhist teaching through verses that have become widely known in the Buddhist world. Eventually they meet the Buddha himself and ordain as monks under him. Maudgalyāyana attains enlightenment shortly after that.

Maudgalyayana | |

|---|---|

Statue of Moggallana, depicting his dark skin color (blue, black). | |

| Title | Foremost disciple, left hand side chief disciple of Sakyamuni Buddha; second chief disciple of Sakyamuni Buddha |

| Personal | |

| Born | year unknown |

| Died | before the Buddha's death Kālasilā Cave, Magadha |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Parents | Mother: Moggalī, father: name unknown |

| School | all |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Sakyamuni Buddha |

Students

| |

| Translations of Maudgalyayana | |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | Maudgalyāyana Sthavira |

| Pali | Moggallāna Thera |

| Burmese | ရှင်မဟာမောဂ္ဂလာန် (IPA: [ʃɪ̀ɴməhàmaʊʔɡəlàɴ]) |

| Chinese | 目連/摩诃目犍乾连 (Pinyin: Mùlián/Mohemujianqian) |

| Japanese | 目犍連 (rōmaji: Mokuren/Mokkenren) |

| Khmer | ព្រះមោគ្គលាន (UNGEGN: Preah Mokkealean) |

| Korean | 摩訶目犍連/目連 (RR: Mongryŏn/Mokkŏllyŏn) |

| Mongolian | Molun Toyin |

| Sinhala | මහා මොග්ගල්ලාන මහ රහතන් වහන්සේ |

| Tibetan | མོའུ་འགལ་གྱི་བུ་ (Mo'u 'gal gy i bu chen po) |

| Tamil | முகிலண்ணர் (Mukilannar) |

| Thai | พระโมคคัลลานะ (RTGS: Phra Mokkhanlana) |

| Vietnamese | Mục-kiền-liên |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Maudgalyayana and Śāriputra have a deep spiritual friendship. They are depicted in Buddhist art as the two disciples that accompany the Buddha, and they have complementing roles as teachers. As a teacher, Maudgalyayana is known for his psychic powers, and he is often depicted using these in his teaching methods. In many early Buddhist canons, Maudgalyāyana is instrumental in re-uniting the monastic community after Devadatta causes a schism. Furthermore, Maudgalyāyana is connected with accounts about the making of the first Buddha image. Maudgalyāyana dies at the age of eighty-four, killed through the efforts of a rival sect. This violent death is described in Buddhist scriptures as a result of Maudgalyāyana's karma of having killed his own parents in a previous life.

Through post-canonical texts, Maudgalyāyana became known for his filial piety through a popular account of him transferring his merits to his mother. This led to a tradition in many Buddhist countries known as the ghost festival, during which people dedicate their merits to their ancestors. Maudgalyāyana has also traditionally been associated with meditation and sometimes Abhidharma texts, as well as the Dharmaguptaka school. In the nineteenth century, relics were found attributed to him, which have been widely venerated.

Person

In the Pali Canon, it is described that Maudgalyāyana had a skin color like a blue lotus or a rain cloud. Oral tradition in Sri Lanka says that this was because he was born in hell in many lifetimes .[1][2] Sri Lankan scholar Karaluvinna believes that originally a dark skin was meant, not blue.[2] In the Mahāsāṃghika Canon, it is stated that he was "beautiful to look at, pleasant, wise, intelligent, full of merits ...", as translated by Migot.[3]

In some Chinese accounts, the clan name Maudgalyāyana is explained as referring to a legume, which was eaten by an ancestor of the clan.[4] However, the Indologist Ernst Windisch linked the life of Maudgalyayana to the figure of Maudgalya (Mugdala) who appears in the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, which would explain the name. Windisch believed the account of the diviner Maudgalya had influenced that of Maudgalyayana, since both relate to a journey to heaven. Author Edward J. Thomas considered this improbable, though. Windisch did consider Maudgalyāyana a historical person.[5]

Life

Meeting the Buddha

According to Buddhist texts, Maudgalyāyana is born in a Brahmin family of the village Kolita (perhaps modern day Kul[6]), after which he is named. His mother is a female Brahmin called Mogallāni, and his father is the village chief of the kshatriya (warrior) caste.[1][6] Kolita is born on the same day as Upatiṣya (Pali: Upatissa; later to be known as Śāriputra), and the two are friends from childhood.[1][7][8] Kolita and Upatiṣya develop an interest in the spiritual life when they are young. One day while they are watching a festival a sense of disenchantment and spiritual urgency overcomes them: they wish to leave the worldly life behind and start their spiritual life under the mendicant wanderer Sañjaya Vairatiputra (Pali: Sañjaya Belatthiputta).[note 1] In the Theravāda and Mahāsāṃghika canons, Sañjaya is described as a teacher in the Indian Sceptic tradition, as he does not believe in knowledge or logic, nor does he answer speculative questions. Since he cannot satisfy Kolita and Upatiṣya's spiritual needs, they leave.[10][11][12] In the Mūlasarvāstivāda Canon, the Chinese Buddhist Canon and in Tibetan accounts, however, he is depicted as a teacher with admirable qualities such as meditative vision and religious zeal. He falls ill though, and dies, causing the two disciples to look further. In some accounts, he even goes so far to predict the coming of the Buddha through his visions.[13][14]

Regardless, Kolita and Upatiṣya leave and continue their spiritual search, splitting up in separate directions. They make an agreement that the first to find the "ambrosia" of the spiritual life will tell the other. What follows is the account leading to Kolita and Upatiṣya taking refuge under the Buddha, which is considered an ancient element of the textual tradition.[15] Upatiṣya meets a Buddhist monk named Aśvajit (Pali: Assaji), one of the first five disciples of the Buddha, who is walking to receive alms from devotees.[1][6] In the Mūlasarvāstivāda version, the Buddha has sent him there to teach Upatiṣya.[16] Aśvajit's serene deportment inspires Upatiṣya to approach him and learn more.[1][17] Aśvajit tells him he is still newly ordained and can only teach a little. He then expresses the essence of the Buddha's teaching in these words:[18][19][note 2]

Of all phenomena sprung from a cause

The Teacher the cause hath told;

And he tells, too, how each shall come to its end,

For such is the word of the Sage.

— Translated by T. W. Rhys Davids[21]

These words help Upatiṣya to attain the first stage on the Buddhist spiritual path. After this, Upatiṣya tells Kolita about his discovery and Kolita also attains the first stage. The two disciples, together with Sañjaya's five hundred students, go to ordain as monks under the Buddha in Veṇuvana (Pali: Veḷuvana).[17][22] From the time of their ordination, Upatiṣya and Kolita become known as Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana, respectively, Maudgalyāyana being the name of Kolita's clan.[23] After having ordained, all except Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana attain arhat (Pali: arahant; last stage of enlightenment).[18][22] Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra attain enlightenment one to two weeks later, Maudgalyāyana in Magadha, in a village called Kallavala.[22][24] At that time, drowsiness is obstructing him from attaining further progress on the path. After he has a vision of the Buddha advising him how to overcome it, he has a breakthrough and attains enlightenment.[18][22] In some accounts, it is said that he meditates on the elements in the process.[25] In the Commentary to the Pali Dhammapada, the question is asked why the two disciples attain enlightenment more slowly than the other former students of Sañjaya. The answer given is that Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana are like kings, who require a longer time to prepare for a journey than commoners. In other words, their attainment is of greater depth than the other students and therefore requires more time.[24]

Aśvajit's brief statement, known as the Ye Dharma Hetu stanza ("Of all phenomena..."), has traditionally been described as the essence of the Buddhist teaching, and is the most inscribed verse throughout the Buddhist world.[17][18][19] It can be found in all Buddhist schools,[6] is engraved in many materials, can be found on many Buddha statues and stūpas (structures with relics), and is used in their consecration rituals.[17][26] According to Indologist Oldenberg and translator Thanissaro Bhikkhu, the verses were recommended in one of Emperor Asoka's edicts as subject of study and reflection.[27][28][note 3] The role of the stanza is not completely understood by scholars. Apart from the complex nature of the statement, it has also been noted it has not anywhere been attributed to the Buddha in this form, which indicates it was Aśvajit's own summary or paraphrasing.[31][17] Indologist T.W. Rhys Davids believed the brief poem may have made a special impression on Maudgalyāyana and Sariputta, because of the emphasis on causation typical for Buddhism.[18] Philosopher Paul Carus explained that the stanza was a bold and iconoclastic response to Brahmanic traditions, as it "repudiates miracles of supernatural interference by unreservedly recognising the law of cause and effect as irrefragable", [26] whereas Japanese Zen teacher Suzuki was reminded of the experience that is beyond the intellect, "in which one idea follows another in sequence finally to terminate in conclusion or judgment".[32][33]

Although in the Pali tradition, Maudgalyāyana is described as an arhat who will no longer be reborn again, in the Mahayāna traditions this is sometimes interpreted differently. In the Lotus Sutra, Chapter 6 (Bestowal of Prophecy), the Buddha is said to predict that the disciples Mahākasyapa, Subhuti, Mahakatyayana, and Maudgalyāyana will become Buddhas in the future.[34][22]

Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana

On the day of Maudgalyāyana's ordination, the Buddha allows him and Śāriputra to take the seats of the chief male disciples.[1] According to the Pali Buddhavaṃsa text, each Buddha has had such a pair of chief disciples.[35] As they have just ordained, some other monks feel offended that the Buddha gives such honor to them. The Buddha responds by pointing out that seniority in the monkhood is not the only criterion in such an appointment, and explains his decision further by relating a story from the past.[1][36] He says that both disciples aspired many lifetimes ago to become chief disciples under him. They made such a resolution since the age of the previous Buddha Aṇomadassī, when Maudgalyāyana was a layman called Sirivadha. Sirivaddha felt inspired to become a chief disciple under a future Buddha after his friend, Śāriputra in a previous life, recommended that he do so. He then invited Buddha Aṇomadassī and the monastic community (Saṃgha) to have food at his house for seven days, during which he made his resolution to become a chief disciple for the first time. Afterwards, he and Śāriputra continued to do good deeds for many lifetimes, until the time of Sakyamuni Buddha.[1] After the Buddha appoints Maudgalyāyana as chief disciple, he becomes known as "Mahā-Maudgalyāyana", mahā meaning 'great'.[37] This epithet is given to him as an honor, and to distinguish him from others of the same name.[38]

Post-canonical texts describe Maudgalyāyana as the second chief male disciple, next to Śāriputra. The early canons agree that Śāriputra is spiritually superior to Maudgalyāyana, and their specializations are described as psychic powers (Sanskrit: ṛddhi, Pali: iddhi) for Maudgalyāyana and wisdom for Śāriputra.[39][note 4] In Buddhist art en literature, Buddhas are commonly depicted with two main disciples (Japanese: niky ōji, Classical Tibetan: mchog zung) at their side—in the case of Sakyamuni Buddha, the two disciples depicted are most often Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra. Although there are different perspectives among different Buddhist canons as to the merits of each disciple, in all Buddhist canons, Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra are recognized as the two main disciples of the Buddha. This fact is also confirmed by iconography as discovered in archaeological findings, in which the two disciples tend to be pictured attending their master.[41] Moreover, Maudgalyāyana is often included in traditional lists of 'four great disciples' (pinyin: sida shengwen)[42] and eight arhats.[43] Despite these widespread patterns in both scripture and archaeological research, it has been noted that in later iconography, Ānanda and Mahākasyapa are depicted much more, and Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra are depicted much less.[44]

The lives of Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra are closely connected. Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra are born on the same day, and die in the same period. Their families have long been friends. In their student years, Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra are co-pupils under the same teacher.[45][46] After having helped each other to find the essence of the spiritual life, their friendship remains. In many sutras they show high appreciation and kindness to one another.[1] For example, when Śāriputra falls ill, it is described that Maudgalyāyana used his psychic powers to obtain medicine for Śāriputra.[47] Śāriputra is considered the wisest disciple of the Buddha, but Maudgalyāyana is second to him in wisdom.[1][48] The one thing that gives them a strong bond as spiritual friends is the love for the Buddha, which both express often.[49]

Role in the community

Several teachings in the Pali Canon are traditionally ascribed to Maudgalyāyana, including several verses in the Theragatha and many sutras in the Samyutta Nikaya. Besides these, there are many passages that describe events in his life. He is seen as learned and wise in ethics, philosophy and meditation. When comparing Śāriputra with Maudgalyāyana, the Buddha uses the metaphor of a woman giving birth to a child for Śāriputra, in that he establishes new students in the first attainment on the spiritual path (Pali: sotāpanna). Maudgalyāyana, however, is compared with the master who trains the child up, in that he develops his students further along the path to enlightenment.[1][51]

The Buddha is described in the texts as placing great faith in Maudgalyāyana as a teacher.[1] He often praises Maudgalyāyana for his teachings, and sometimes has Maudgalyāyana teach in his place.[52][53] Maudgalyāyana is also given the responsibility to train Rahula, the Buddha's son. On another occasion, the Buddha has Maudgalyāyana announce a ban on a group of monks living in Kitigara, whose problematic behavior has become widely known in the area.[54] Furthermore, Maudgalyāyana plays a crucial role during the schism caused by the disciple Devadatta. Through his ability to communicate with devas (god-like beings), he learns that Devadatta was acting inappropriately. He obtains information that Devadatta is enjoining Prince Ajatasatru (Pali: Ajatasattu) for help, and the two form a dangerous combination. Maudgalyāyana therefore informs the Buddha of this.[55][56] Later, when Devadatta has successfully created a split in the Buddhist community, the Buddha asks Maudgalyāyana and Śāriputra to convince Devadatta's following to reunite with the Buddha, which in the Pali account they are able to accomplish.[1][50][note 5] Because Devadatta believes they come to join his following, he lets his guard down. They then persuade the other monks to return while Devadatta is asleep. After the split off party has successfully been returned to the Buddha, Maudgalyāyana expresses astonishment because of Devadatta's actions. The Buddha explains that Devadatta had acted like this habitually, throughout many lifetimes. In the Vinaya texts of some canons, the effort at persuading the split off monks is met with obstinacy and fails. French Buddhologist André Bareau believes this latter version of the account to be historically authentic, which he further supports by the report of the Chinese pilgrim Xuan Zang, twelve centuries later, that Devadatta's sect had still continued to exist.[58]

Teaching through psychic powers

In the Anguttara Nikaya, Maudgalyāyana is called foremost in psychic powers.[59][60] In teaching, Maudgalyāyana relies much on such powers. Varying accounts in the Pali Canon show Maudgalyāyana travelling to and speaking with pretas (spirits in unhappy destinations) in order to explain to them their horrific conditions. He helps them understand their own suffering, so they can be released from it or come to terms with it. He then reports this to the Buddha, who uses these examples in his teachings.[1][50] Similarly, Maudgalyāyana is depicted as conversing with devas and brahmas (heavenly beings), and asking devas what deeds they did to be reborn in heaven.[50][61] In summary, Maudgalyāyana's meditative insights and psychic powers are not only to his own benefit, but benefit the public at large. In the words of historian Julie Gifford, he guides others "by providing a cosmological and karmic map of samsara".[62]

Maudgalyāyana is able to use his powers of mind-reading in order to give good and fitting advice to his students, so they can attain spiritual fruits quickly.[63] He is described as using his psychic powers to discipline not only monks, but also devas and other beings. One day some monks are making noise as they were sitting in the same building as the Buddha. Maudgalyāyana then shakes the building, to teach the monks to be more restrained.[50][64] But the most-quoted example of Maudgalyāyana's demonstration of psychic powers is his victory over the dragon (naga) Nandopananda, which requires mastery of the jhānas (states in meditation).[22][48] Many of his demonstrations of psychic powers are an indirect means of establishing the Buddha as a great teacher. People ask themselves, if the disciple has these powers, then how spiritually powerful will his teacher be?[65]

Rescuing his mother

The account of Maudgalyāyana looking for his mother after her death is widespread. Apart from being used to illustrate the principles of karmic retribution and rebirth,[66][67] in China, the story developed a new emphasis. There Maudgalyāyana was known as "Mulian", and his story was taught in a mixture of religious instruction and entertainment, to remind people of their duties to deceased relatives.[68][69] Its earliest version being the Sanskrit Ullambana Sutra,[70] the story has been made popular in China, Japan, and Korea through edifying folktales such as the Chinese bianwen (for example, The Transformation Text on Mu-lien Saving His Mother from the Dark Regions).[71][72] In most versions of the story, Maudgalyāyana uses his psychic powers to look for his deceased parents and see in what world they have been reborn. Although he can find his father in a heaven, he cannot find his mother and asks the Buddha for help. The Buddha brings him to his mother, who is located in a hell realm, but Maudgalyāyana cannot help her. The Buddha then advises him to make merits on his mother's behalf, which helps her to be reborn in a better place.[72][73][74] In the Laotian version of the story, he travels to the world of Yama, the ruler of the underworld, only to find the world abandoned. Yama then tells Maudgalyāyana that he allows the denizens of the hell to go out of the gates of hell to be free for one day, that is, on the full moon day of the ninth lunar month. On this day, the hell beings can receive merit transferred and be liberated from hell, if such merit is transferred to them.[75] In some other Chinese accounts, Maudgalyāyana finds his mother, reborn as a hungry ghost. When Maudgalyāyana tries to offer her food through an ancestral shrine, the food bursts into flames each time. Maudgalyāyana therefore asks the Buddha for advice, who recommends him to make merit to the Saṃgha and transfer it to his mother. The transfer not only helps his mother to be reborn in heaven, but can also be used to help seven generations of parents and ancestors.[76][77] The offering was believed to be most effective when collectively done, which led to the arising of the ghost festival.[78]

Several scholars have pointed out the similarities between the accounts of Maudgalyāyana helping his mother and the account of Phra Malai, an influential legend in Thailand and Laos.[79][80] Indeed, in some traditional accounts Phra Malai is compared to Maudgalyāyana.[80] On a similar note, Maudgalyāyana's account is also thought to have influenced the Central Asian Epic of King Gesar, Maudgalyāyana being a model for the king.[81]

Making the Udāyana image

Another account involving Maudgalyayana, related in the Chinese translation of the Ekottara Agāma, in the Thai Jinakālamālī and the post-canonical Paññāsajātakā, was the production of what was described as the first Buddha image, the Udāyana Buddha. The account relates that the Buddha pays a visit to the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven (Pali: Tāvatiṃsa) to teach his mother. King Udāyana misses the Buddha so much that he asks Maudgalyāyana to use his psychic powers to transport thirty-two craftsmen to the heaven, and make an image of the Buddha there.[82][83] The image that is eventually made is from sandalwood, and many accounts have attempted to relate it to later Buddha images in other areas and countries.[84][85] Although the traditional accounts mentioned state that the Udāyana Buddha was the first image, there were probably several Buddha images preceding the Udāyana Buddha, made by both kings and commoners.[86] It could also be that these accounts originate from the same common narrative about a first Buddha image.[87]

Death

According to the Pali tradition, Maudgalyāyana's death comes in November of the same year as the Buddha's passing, when Maudgalyāyana is traveling in Magadha. He dies at the age of eighty-four.[88] Some accounts put forth that rivaling traditions stone him to death, others say that those people hire robbers. The Pali tradition states that Jain monks persuade a group of robbers led by a Samaṇa-guttaka to kill Maudgalyāyana, out of jealousy for his success. Maudgalyāyana often teaches about the visits he has made to heaven and hell, the fruits of leading a moral life, and the dangers of leading an immoral life. These teachings make the number of followers from rivaling traditions decrease.[2][51] Whoever kills Maudgalyāyana, the general agreement among different accounts is that he is killed in a violent fashion at the Kālasilā Cave, on the Isigili Hill near Rājagaha,[1][51] which might be equated with modern Udaya Hill.[89]

At that time, Maudgalyāyana dwells alone in a forest hut. When he sees the bandits approaching, he makes himself vanish with psychic powers. The bandits find an empty hut, and although they search everywhere, they find nobody. They leave and return on the following day, for six consecutive days, with Maudgalyāyana escaping from them in the same way.[90][91] On the seventh day, Maudgalyāyana suddenly loses the psychic powers he has long wielded. Maudgalyāyana realizes that he is now unable to escape. The bandits enter, beat him repeatedly and leave him lying in his blood. Being keen on quickly getting their payment, they leave at once.[1][92] Maudgalyāyana's great physical and mental strength is such that he is able to regain consciousness and is able to journey to the Buddha.[1][65] In some accounts, he then returns to Kalasila and dies there, teaching his family before dying. In other accounts, he dies in the Buddha's presence.[22][93]

It is described that in a previous life, Maudgalyāyana is the only son born to his family. He is dutiful, and takes care of all the household duties. As his parents age, this increases his workload. His parents urge him to find a wife to help him, but he persistently refuses, insisting on doing the work himself. After persistent urging from his mother, he eventually marries.[94] His wife looks after his elderly parents, but after a short period becomes hostile to them. She complains to her husband, but he pays no attention to this. One day, when he is outside the house, she scatters rubbish around and when he returns, blames it on his blind parents. After continual complaints, he capitulates and agrees to deal with his parents. Telling his parents that their relatives in another region wish to see them, he leads his parents onto a carriage and begins driving the oxen cart through the forest. While in the depths of the forest, he dismounts and walks along with the carriage, telling his parents that he has to watch out for robbers, which are common in the area. He then impersonates the sounds and cries of thieves, pretending to attack the carriage. His parents tell him to fend for himself (as they are old and blind) and implore the imaginary thieves to leave their son. While they are crying out, the man beats and kills his parents, and throws their bodies into the forest before returning home.[94][95] In another version recorded in the commentary to the Pali Jātaka, Maudgalyāyana does not carry the murder through though, touched by the words of his parents.[1][96]

After Maudgalyāyana's death, people ask why Maudgalyāyana had not protected himself, and why a great enlightened monk would suffer such a death. The Buddha then says that because Maudgalyāyana has contracted such karma in a previous life (the murder of one's own parents is one of the five heinous acts that reap the worst karma), so he could not avoid reaping the consequences. He therefore accepted the results. [97][22] Further, the Buddha states that even psychic powers will be of no use in avoiding karma, especially when it is serious karma.[88][22] Shortly after having left Maudgalyāyana for dead, the bandits are all executed. Religious Studies scholar James McDermott therefore concludes that there must have been "a confluence" of karma between Maudgalyāyana and the bandits, and cites the killing as evidence that in Buddhist doctrine the karma of different individuals can interact.[92] Indologist Richard Gombrich raises the example of the murder to prove another point: he points out that Maudgalyāyana is able to attain enlightenment, despite his heavy karma from a past life. This, he says, shows that the Buddha teaches everyone can attain enlightenment in the here and now, rather than enlightenment necessarily being a gradual process built up through many lifetimes.[98]

Gifford speculates that Maudgalyāyana believes he is experiencing heavy karma from a past life. This awareness leads him to want to prevent others from making the same mistakes and leading an unethical life. This may be the reason why he is so intent on teaching about the law of karmic retribution.[99]

After Maudgalyāyana's and Śāriputra's death, the Buddha states the monastic community has now become less, just like a healthy tree has some branches that have died off. Then he adds to that all impermanent things must perish.[89] In some accounts of Maudgalyāyana's death, many of his students fall ill after his death, and die as well.[100]

Heritage

In Buddhist history, Maudgalyāyana has been honored for several reasons. In some canons such as the Pali Tipiṭaka, Maudgalyāyana is held up by the Buddha as an example which monks should follow.[1][59] The Pali name Moggallāna was used as a monastic name by Buddhist monks up until the twelfth century C.E.[51]

In East Asia, Maudgalyāyana is honored as a symbol of filial piety and psychic powers.[102][103] Maudgalyāyana has had an important role in many Mahāyāna traditions. The Ullambana Sutra is the main Mahāyāna sūtra in which Maudgalyāyana's rescue of his mother is described .[50][104] The sutra was highly influential, judging from the more than sixty commentaries that were written about it.[70] Although the original Sanskrit sutra already encouraged filial piety, later Chinese accounts inspired by the sutra emphasized this even more. Furthermore, Chinese accounts described merit-making practices and filial piety as two inseparable sides of the same coin.[105] The sūtra became popular in China, Japan, and Korea, and led to the Yulan Hui (China) and Obon (Japan) festivals.[106][71][107] This festival probably spread from China to Japan in the seventh century,[108] and similar festivals have been observed in India (Avalamba), Laos and Vietnam.[106][109] The festival is celebrated on the seventh lunar month (China; originally only on the full moon, on the Pravāraṇa Day[110]), or from 13 to 15 July (Japan). It is believed that in this period ancestors reborn as pretas or hungry ghosts wander around.[106][101][111] In China, this was the time when the yearly varṣa for monastics came to an end (normally translated as rains retreat, but in China this was a Summer Retreat).[112] It was a time that the monastics completed their studies and meditation, which was celebrated.[113] Up until the present day, people make merits and transfer merit through several ceremonies during the festival, so the spirits may be reborn in a better rebirth.[101][111] The festival is also popular among non-Buddhists,[101] and has led Taoists to integrate it in their own funeral services.[114][115]

The festival has striking similarities to Confucian and Neo-Confucian ideals, in that it deals with filial piety.[116] It has been observed that the account of rescuing the mother in hell has helped Buddhism to integrate into Chinese society. At the time, due to the Buddhist emphasis on the renunciant life, Buddhism was criticized by Confucianists. They felt Buddhism went against the principle of filial piety, because Buddhist monks did not have offspring to make offerings for ancestor worship.[70][78] Maudgalyāyana's account helped greatly to improve this problem, and has therefore been raised as a textbook example of the adaptive qualities of Buddhism.[117] Other scholars have proposed, however, that the position of Buddhism in India versus China was not all that different, as Buddhism had to deal with the problem of filial piety and renunciation in India as well.[118] Another impact the story of Maudgalyāyana's had was that, in East Asia, the account helped to shift the emphasis of filial piety towards the mother, and helped redefine motherhood and femininity.[70]

Apart from the Ghost Festival, Maudgalyāyana also has an important role in the celebration of Māgha Pūjā in Sri Lanka. On Māgha Pūjā, in Sri Lanka called Navam Full Moon Poya, Maudgalyāyana's appointment as a chief disciple of the Buddha is celebrated by various merit-making activities, and a pageant.[119][120]

There are several canonical and post-canonical texts that are traditionally connected to the person of Maudgalyāyana. In the Theravāda tradition, the Vimānavatthu is understood to be a collection of accounts related by Maudgalyayana to the Buddha, dealing with his visits to heavens.[121] In the Sarvāstivāda tradition, Maudgalyāyana is said to have composed the Abhidharma texts called the Dharmaskandha and the Prajñāptibhāsya,[122][123] although in some Sanskrit and Tibetan scriptures the former is attributed to Śāriputra.[124] Scholars have their doubts on whether Maudgalyāyana was really the author of these works.[124] They do believe, however, that Maudgalyāyana and some other main disciples compiled lists (Sanskrit: mātṛikā, Pali: mātikā) of teachings as mnemonic devices. These lists formed the basis for what later became the Abhidharma.[125] Despite these associations with Abhidharma texts, pilgrim Xuan Zang reports that during his visits in India, Śāriputra was honored by monks for his Abhidharma teachings, whereas Maudgalyāyana was honored for his meditation, the basis for psychic powers.[126][127] French scholar André Migot has proposed that in most text traditions Maudgalyāyana was associated with meditation and psychic powers, as opposed to Śāriputra's specialization in wisdom and Abhidharma.[127][128]

Traditions have also connected Maudgalyāyana with the symbol of the Wheel of Becoming (Sanskrit: bhavacakra, Pali: bhavacakka). Accounts in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya and the Divyāvadāna relate that Ānanda once told the Buddha about Maudgalyāyana's good qualities as a teacher. Maudgalyayana was a very popular teacher, and his sermons with regard to afterlife destinations were very popular. The Buddha said that in the future, a person like him would be hard to find. The Buddha then had an image painted on the gate of the Veluvaḷa monastery to honor Maudgalyāyana, depicting the Wheel of Becoming. This wheel showed the different realms of the cycle of existence, the three poisons in the mind (greed, hatred and delusion), and the teaching of dependent origination. The wheel was depicted as being in the clutches of Māra, but at the same time included the symbol of a white circle for Nirvana. The Buddha further decreed that a monk be stationed at the painting to explain the law of karma to visitors.[129][130][131] Images of the Wheel of Becoming are widespread in Buddhist Asia, some of which confirm and depict the original connection with Maudgalyāyana.[132]

Finally, there was also an entire tradition that traces its origins to Maudgalyayana, or to a follower of him, called Dharmagupta: this is the Dharmaguptaka school, one of the early Buddhist schools.[133][134]

Relics

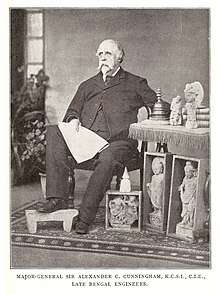

Sir Alexander Cunningham, The Bhilsa topes[135]

In a Pali Jātaka account, the Buddha is said to have had the ashes of Maudgalyāyana collected and kept in a stūpa in the gateway of the Veluvaḷa.[1][136] In two other accounts, however, one from the Dharmaguptaka and the other from the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition, Anāthapiṇḍika and other laypeople requested the Buddha to build a stūpa in honor of Maudgalyāyana.[137] According to the Divyāvadāna, emperor Ashoka visited the stūpa and made an offering, on the advice of Upagupta Thera.[2] During the succeeding centuries, Xuan Zang and other Chinese pilgrims reported that a stūpa with Maudgalyāyana's relics could be found under the Indian city Mathura, and in several other places in Northeast India. However, as of 1999, none of these had been confirmed by archaeological findings.[138][139]

An important archaeological finding was made elsewhere, however. In the nineteenth century, archaeologist Alexander Cunningham and Lieutenant Fred. C. Maisey discovered bone fragments in caskets, with Maudgalyāyana's and Śāriputra's names inscribed on it, both in the Sanchi Stūpa and at the stūpas at Satdhāra, India.[51][140] The caskets contained pieces of bone and objects of reverence, including sandalwood which Cunningham believed had once been used on the funeral pyre of Śāriputra.[141] The finding was important in several ways, and was dated from the context to the second century BCE.[142]

Initially, Cunningham and Maisey divided the shares of the discovered items and had them shipped to Britain. Since some of Cunningham's discovered items were lost when one ship sank, some scholars have understood that the Sanchi relics were lost.[143] However, in a 2007 study, the historian Torkel Brekke used extensive historical documents to argument that it was Maisey who took all the relics with him, not Cunningham. This would imply that the relics reached Britain in their entirety. After the relics reached Britain, they were given to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1866.[144][note 6] When the relics were given to the V&A Museum, pressure from Buddhists to return the relics to their country of origin arose. Although at first the museum dismissed the complaints as coming from a marginal community of English Buddhists, when several Buddhist societies in India took notice, as well as societies in other Asian countries, it became a serious matter. Eventually, the museum was pressured by the British government to return the relics and their original caskets, for diplomatic reasons. After many requests and much correspondence, the museum had the relics brought back to the Sri Lankan Maha Bodhi Society in 1947.[147][148] They were formally re-installed into a shrine at Sanchi, India, in 1952, after it had been agreed that Buddhists would continue to be their caretaker, and a long series of ceremonies had been held to pay due respect. The relics were paraded through many countries in South and Southeast Asia, in both Theravāda and Mahāyāna countries.[149][148] At the same time, Indian Prime Minister Nehru used the opportunity to propagate a message of unity and religious tolerance, and from a political perspective, legitimate state power.[150] Indeed, even for other countries, such as Burma, in which the relics were shown, it helped to legitimate the government, create unity, and revive religious practice: "those tiny pieces of bone moved not only millions of devotees worldwide, but national governments as well", as stated by art historian Jack Daulton. For these reasons, Burma asked for a portion of the relics to keep there. In ceremonies attended by hundred of thousands people, the relics were installed in the Kaba Aye Pagoda, in the same year as India.[151]

Sri Lanka also obtained a portion, kept at the Maha Bodhi Society, which is annually exhibited during a celebration in May.[152] In 2015, the Catholic world was surprised to witness that the Maha Bodhi Society broke with tradition by showing the relics to Pope Francis on a day outside of the yearly festival. Responding to critics, the head of the society stated that no pope had set foot inside a Buddhist temple since 1984, and added that "religious leaders have to play a positive role to unite [their] communities instead of dividing".[153] As for the original Sanchi site in India, the relics are shown every year on the annual international Buddhist festival in November. As of 2016, the exhibition was visited by hundred thousands visitors from over the world, including Thai princess Sirindhorn.[154][155]

See also

- The ten principal disciples

Notes

- According to some Chinese accounts, Maudgalyāyana waits until after his mother has died, and only after having mourned her for three years. But this may be a Confucian addition to the story.[9]

- Some schools, such as the Mahīśāsaka school, relate this verse differently, with one line about the emptiness of the Dharma.[20]

- Most scholars lean towards the interpretation that Emperor Asoka referred to the text Sariputta Sutta instead. However, this consensus is still considered tentative.[29][30]

- Contradicting the fact that the canons state Śāriputra was spiritually the superior of Maudgalyāyana, in the popular traditions of China, Maudgalyāyana was actually more popular than Śāriputra, Maudgalyāyana often being depicted as a sorcerer.[40]

- In the Dharmaguptaka, Sarvāstivāda and Mūlasarvāstivāda canons, it is their own proposal to go, for which they ask the Buddha his permission.[57]

- At the time, the museum was still called the South Kensington Museum.[145] Already in 1917, archeologist Louis Finot stated that Cunningham had no interest in the relics, only in the caskets.[146]

Citations

- Malalasekera 1937.

- Karaluvinna 2002, p. 452.

- Migot 1954, p. 433.

- Teiser 1996, p. 119.

- Thomas, Edward J. (1908). "Saints and martyrs (Buddhist)" (PDF). In Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Gray, Louis H. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics. 11. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. p. 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-25.

- Schumann 2004, p. 94.

- Thakur, Amarnath (1996). Buddha and Buddhist synods in India and abroad. p. 66.

- Rhys Davids 1908, pp. 768–9.

- Ditzler, Pearce & Wheeler 2015, p. 9.

- Harvey 2013, p. 14.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, pp. 1012–3.

- Migot 1954, p. 434.

- Lamotte, E. (1947). "La légende du Buddha" [The legend of the Buddha]. Revue de l'histoire des religions (in French). 134 (1–3): 65–6. doi:10.3406/rhr.1947.5599.

- Migot 1954, pp. 430–2, 440, 448.

- Migot 1954, p. 426.

- Migot 1954, p. 432.

- Skilling 2003, p. 273.

- Rhys Davids 1908, p. 768.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 77.

- Migot 1954, pp. 429, 439.

- Rhys Davids 1908.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 499.

- Migot 1954, pp. 412, 433.

- Migot 1954, pp. 451–3.

- Migot 1954, pp. 435, 438, 451.

- Carus 1905, p. 180.

- Bhikkhu, Thanissaro (1993). "That the True Dhamma Might Last a Long Time: Readings Selected by King Asoka". Access to Insight (Legacy Edition). Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Migot 1954, p. 413.

- Neelis, Jason (2011). Early Buddhist transmission and trade networks : mobility and exchange within and beyond the northwestern borderlands of South Asia (PDF). Dynamics in the History of Religions. 2 (illustrated ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 89–90 n72. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-20.

- Wilson (1856). "Buddhist Inscription of King Priyadarśi: Translation and Observations". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. West Strand: John W. Parker and Son. 16: 363–4.

- De Casparis, J.G. (1990). "Expansion of Buddhism into South-east Asia" (PDF). Ancient Ceylon (14): 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-20.

- Suzuki, D. T. (2007). Essays in Zen Buddhism. Grove Atlantic. ISBN 978-0-8021-9877-8.

- Migot 1954, p. 449.

- Tsugunari, Kubo (2007). The Lotus Sutra (PDF). Translated by Akira, Yuyama (revised 2nd ed.). Berkeley, California: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. pp. 109–11. ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2015.

- Shaw 2013, p. 455.

- Epasinghe, Premasara (29 January 2010). "Why Navam Poya is important?". The Island (Sri Lanka). Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Migot 1954.

- Epstein, Ron (October 2005). "Mahāmaudgalyāyana Visits Another Planet: A Selection from the Scripture Which Is a Repository of Great Jewels". Religion East and West (5). note 2. Archived from the original on 2017-05-02.

- Migot 1954, pp. 510–1.

- Mair, Victor H. (2014). "Transformation as Imagination". In Kieschnick, John; Shahar, Meir (eds.). India in the Chinese imagination (1st ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 221 n.16. ISBN 978-0-8122-0892-4.

- Migot 1954, pp. 407, 416–7.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, pp. 287, 456.

- Shaw 2013, p. 452.

- Migot 1954, pp. 417–9, 477, 535.

- Karaluvinna 2002, p. 448.

- Migot 1954, pp. 433, 475.

- Migot 1954, p. 478.

- Karaluvinna 2002, p. 450.

- Karaluvinna 2002, p. 451.

- Mrozik 2004, p. 487.

- Rhys Davids 1908, p. 769.

- Karaluvinna 2002, p. 250.

- Schumann 2004, p. 232.

- Brekke, Torkel (1997). "The Early Saṃgha and the Laity". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 20 (2): 28. Archived from the original on 2017-05-06.

- Schumann 2004, p. 233.

- Bareau 1991, p. 93.

- Bareau 1991, p. 111.

- Bareau 1991, pp. 92, 103–4, 124.

- Karaluvinna 2002, p. 449.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 498.

- Gifford 2003, pp. 74–5.

- Gifford 2003, pp. 72, 77.

- Gethin 2011, p. 222.

- Gethin 2011, p. 226.

- Gifford 2003, p. 74.

- Ladwig 2012.

- Berezkin 2015, sec. 3.

- Berezkin 2015, sec. 7.

- Ladwig 2012, p. 137.

- Berezkin 2015, sec. 2.

- Berezkin 2015, sec. 6.

- Teiser 1996, p. 6.

- Irons 2007, pp. 54, 98.

- Powers 2015, p. 289.

- Ladwig 2012, p. 127.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, pp. 499, 1045.

- Teiser 1996, p. 7.

- Seidel 1989, p. 295.

- Ladwig, Patrice (June 2012). "Visitors from hell: transformative hospitality to ghosts in a Lao Buddhist festival". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 18: S92–3. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2012.01765.x. Archived from the original on 2017-05-10.

- Gifford 2003, p. 76.

- Mikles, Natasha L. (December 2016). "Buddhicizing the Warrior-King Gesar in the dMyal gling rDzogs pa Chen po" (PDF). Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines (37): 236. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-04-27.

- Karlsson, Klemens (May 2009). "Tai Khun Buddhism And Ethnic–Religious Identity" (PDF). Contemporary Buddhism. 10 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1080/14639940902968939.

- Brown, Frank Burch, ed. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Religion and the Arts. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-19-972103-0.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, pp. 932-3.

- Revire 2017, p. 4.

- Huntington, J.C. (1985). Narain, A. K. (ed.). "The Origin of the Buddha Image: Early Image Traditions and the Concept of Buddhadarsanapunya" (PDF). Studies in Buddhist Art of South Asia. Delhi: 48–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-11.

- Revire 2017, p. 8.

- Hecker, Hellmuth (1979). "Mahamoggallana". Buddhist Publication Society. Archived from the original on 2006-02-18.

- Schumann 2004, p. 244.

- McDermott 1976, p. 77.

- Keown 1996, p. 342.

- McDermott 1976, p. 78.

- Migot 1954, p. 476.

- Weragoda Sarada Maha Thero (1994). Parents and Children: Key to Happiness. ISBN 981-00-6253-2.

- Hoffman, L.; Patz-Clark, D.; Looney, D.; Knight, S. K. (2007). Historical perspectives and contemporary needs in the psychology of evil: Psychological and interdisciplinary perspectives. 115th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association. San Francisco, California. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2017-05-06.

- Keown 1996, p. 341.

- Kong, C.F. (2006). Saccakiriyā: The Belief in the Power of True Speech in Theravāda Buddhist Tradition (PhD thesis, published as a book in 2012). School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 211 n.2. uk.bl.ethos.428120.

- Gombrich, Richard (1975). "Buddhist karma and social control" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 17 (2): 215 n.7. ISSN 1475-2999.

- Gifford 2003, p. 82.

- Migot 1954, p. 475.

- Harvey 2013, pp. 262–3.

- Mrozik 2004, p. 488.

- Irons 2007, p. 335.

- Harvey 2013, p. 263.

- Ditzler, Pearce & Wheeler 2015, p. 13.

- Wu, Fatima (2004). "China: Popular Religion". In Salamone, Frank A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals (new ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 0-415-94180-6.

- Harvey 2013, p. 262.

- Irons 2007, p. 54.

- Williams, Paul; Ladwig, Patrice (2012). Buddhist funeral cultures of Southeast Asia and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-107-00388-0.

- Ashikaga 1951, p. 71 n.2.

- Powers 2015, p. 290.

- Teiser 1996, pp. 7, 20–1.

- Ashikaga 1951, p. 72.

- Xing, Guang (2010). "Popularization of Stories and Parables on Filial Piety in China". Journal of Buddhist Studies (8): 131. ISSN 1391-8443. Archived from the original on 2015-01-20.

- Seidel 1989, p. 268.

- Ditzler, Pearce & Wheeler 2015, p. 5.

- Ditzler, Pearce & Wheeler 2015, pp. 6, 13.

- Strong, John (1983). "Filial piety and Buddhism: The Indian antecedents to a "Chinese" problem" (PDF). In Slater, P.; Wiebe, D. (eds.). Traditions in contact and change: selected proceedings of the XIVth Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions. 14. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-06.

- Dias, Keshala (10 February 2017). "Today is Navam Full Moon Poya Day". News First. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- "The Majestic Navam Perahera of Gangaramaya". Daily Mirror. 22 February 2016. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013.

- Prebish, Charles S. (2010). Buddhism: A Modern Perspective. Penn State Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-271-03803-2.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, pp. 7, 252.

- Migot 1954, p. 520.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 535.

- Gifford 2003, p. 78.

- Strong, John S. (1994). The Legend and Cult of Upagupta: Sanskrit Buddhism in North India and Southeast Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 978-81-208-1154-6.

- Migot 1954, pp. 509, 514, 517.

- Huber, E. (1906). "Etudes de littérature bouddhique" [Studies in Buddhist literature]. Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 6: 27–8. doi:10.3406/befeo.1906.2077.

- Thomas 1953, pp. 68–9.

- Teiser 2008, p. 141.

- Teiser 2008, pp. 145–6.

- Irons 2007, p. 158.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 245.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854). The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India: comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa (PDF). London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 191.

- Brekke 2007, p. 275.

- Bareau, André (1962). "La construction et le culte des stūpa d'après les Vinayapitaka" [The construction and cult of the stūpa after the Vinayapitaka]. Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 50 (2): 264. doi:10.3406/befeo.1962.1534.

- Higham, Charles F.W. (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. New York: Facts On File. p. 215. ISBN 0-8160-4640-9.

- Daulton 1999, p. 104.

- Migot 1954, p. 416.

- Brekke 2007, p. 274.

- Daulton 1999, p. 107.

- Daulton 1999, p. 108.

- Brekke 2007, pp. 273–78.

- Brekke 2007, p. 78.

- Finot, Louis (1917). "Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Part I, 1915–1916; Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report, 1913–1914". Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient. 17: 12.

- Brekke 2007, pp. 277–95.

- Daulton 1999, pp. 108–13.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (February 1954). "Book review of The Visit of the Sacred Relics of the Buddha and the Two Chief Disciples to Tibet at the Invitation of the Government". The Far Eastern Quarterly. The Government of Tibet. 13 (2): 223–225. doi:10.2307/2942082. JSTOR 2942082.

- Brekke 2007, pp. 295–7, 301.

- Daulton 1999, pp. 115–20.

- Santiago, Melanie (3 May 2015). "Sacred Relics of Lord Buddha brought to Sirasa Vesak Zone; thousands gather to pay homage". News First. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Akkara, Anto (15 January 2015). "Buddhist center breaks tradition, shows pope revered relic". Catholic Philly. Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Santosh, Neeraj (27 November 2016). "Relics of the Buddha's chief disciples exhibited in Sanchi". Hindustan Times. Bhopal. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- "Thai princess visits Sanchi". Hindustan Times. Bhopal. 22 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017.

References

- Ashikaga, Ensho (1 January 1951), "Notes on Urabon ("Yü Lan P'ên, Ullambana")", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 71 (1): 71–75, doi:10.2307/595226, JSTOR 595226

- Bareau, André (1991), "Les agissements de Devadatta selon les chapitres relatifs au schisme dans les divers Vinayapitaka" [Devadatta's deeds according to the chapters relating the schism in the various Vinayapitakas], Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), 78: 87–132, doi:10.3406/befeo.1991.1769

- Berezkin, Rostislav (21 February 2015), "Pictorial Versions of the Mulian Story in East Asia (Tenth–Seventeenth Centuries): On the Connections of Religious Painting and Storytelling", Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 8 (1): 95–120, doi:10.1007/s40647-015-0060-4

- Brekke, Torkel (1 September 2007), "Bones of Contention: Buddhist Relics, Nationalism and the Politics of Archaeology", Numen, 54 (3): 270–303, doi:10.1163/156852707X211564

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013), Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. (PDF), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3

- Carus, Paul (1905), "Ashvajit's Stanza and Its Signigicance", Open Court, 3 (6)

- Daulton, J. (1999), "Sariputta and Moggallana in the Golden Land: The Relics of the Buddha's Chief Disciples at the Kaba Aye Pagoda" (PDF), Journal of Burma Studies, 4 (1): 101–128, doi:10.1353/jbs.1999.0002

- Ditzler, E.; Pearce, S.; Wheeler, C. (May 2015), The Fluidity and Adaptability of Buddhism: A Case Study of Maudgalyāyana and Chinese Buddhist identity

- Gethin, Rupert (2011), "Tales of miraculous teachings: miracles in early Indian Buddhism", in Twelftree, Graham H. (ed.), The Cambridge companion to miracles, Cambridge Companions to Religions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89986-4

- Gifford, Julie (2003), "The Insight Guide to Hell" (PDF), in Holt, John Clifford; Kinnard, Jacob N.; Walters, Jonathan S. (eds.), Constituting communities Theravada Buddhism and the religious cultures of South and Southeast Asia, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-5691-9

- Harvey, Peter (2013), An introduction to Buddhism: teachings, history and practices (PDF) (second ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4

- Irons, Edward (2007), Encyclopedia of Buddhism (PDF), New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-8160-5459-6

- Karaluvinna, M. (2002), "Mahā-Moggallāna", in Malalasekera, G. P.; Weeraratne, W. G. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, 6 (fasc. 3), Government of Sri Lanka

- Keown, D. (1996), "Karma, character, and consequentialism", The Journal of Religious Ethics (24)

- Ladwig, Patrice (2012), "Feeding the dead: ghosts, materiality and merit", in Williams, Paul; Ladwig, Patrice (eds.), Buddhist funeral cultures of Southeast Asia and China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-00388-0

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1937), Dictionary of Pāli proper names, 2 (1st Indian ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-3022-9

- McDermott, James P. (1 January 1976), "Is There Group Karma in Theravāda Buddhism?", Numen, 23 (1): 67–80, doi:10.2307/3269557, JSTOR 3269557

- Migot, André (1954), "Un grand disciple du Buddha: Sāriputra. Son rôle dans l'histoire du bouddhisme et dans le développement de l'Abhidharma" [A great disciple of the Buddha: Sāriputra, his role in Buddhist history and in the development of Abhidharma] (PDF), Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), 46 (2), doi:10.3406/befeo.1954.5607

- Mrozik, Suzanne (2004), "Mahāmaudgalyāyana" (PDF), in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, New York [u.a.]: Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale, pp. 487–8, ISBN 0-02-865720-9

- Powers, John (2015), The Buddhist World, Routledge Worlds, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-42017-0

- Revire, Nicolas (March 2017), "Please Be Seated": Faxian's Account and Related Legends Concerning the First Buddha Image, Changzhi

- Rhys Davids, T.W. (1908), "Moggallāna", in Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Gray, Louis H. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics, 8, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark

- Schumann, H.W. (2004) [1982], Der Historische Buddha [The historical Buddha: the times, life, and teachings of the founder of Buddhism] (in German), translated by Walshe, M. O' C., Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1817-2

- Seidel, Anna (1989), "Chronicle of Taoist Studies in the West 1950–1990", Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, 5: 223–347, doi:10.3406/asie.1989.950

- Shaw, Sarah (2013), "Character, Disposition, and the Qualities of the Arahats as a Means of Communicating Buddhist Philosophy in the Suttas" (PDF), in Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.), A companion to Buddhist philosophy (first ed.), Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-470-65877-2

- Skilling, Peter (2003), "Traces of the Dharma", Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient, 90–1: 273–287, doi:10.3406/befeo.2003.3615

- Teiser, Stephen F. (1996), The ghost festival in medieval China (2nd ed.), Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-02677-7

- Teiser, Stephen F. (2008), "The Wheel of Rebirth in Buddhist Temples", Arts Asiatiques, 63: 139–153, doi:10.3406/arasi.2008.1666

- Thomas, Edward J. (1953), The History of Buddhist Thought (PDF), History of Civilization (2nd ed.), London: Routledge and Kegan Paul