Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery, or neurological surgery, is the medical specialty concerned with the prevention, diagnosis, surgical treatment, and rehabilitation of disorders which affect any portion of the nervous system including the brain, spinal cord, central and peripheral nervous system, and cerebrovascular system.[1]

Stereotactic guided insertion of DBS electrodes in neurosurgery | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Activity sectors | Surgery |

| Description | |

Education required |

or

or

or |

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

Education and context

In different countries, there are different requirements for an individual to legally practice neurosurgery, and there are varying methods through which they must be educated. In most countries, neurosurgeon training requires a minimum period of seven years after graduating from medical school.[2]

United States

In the United States, a neurosurgeon must generally complete four years of undergraduate education, four years of medical school, and seven years of residency (PGY-1-7).[3] Most, but not all, residency programs have some component of basic science or clinical research. Neurosurgeons may pursue additional training in the form of a fellowship, after residency or in some cases as a senior resident in the form of an enfolded fellowship. These fellowships include pediatric neurosurgery, trauma/neurocritical care, functional and stereotactic surgery, surgical neuro-oncology, radiosurgery, neurovascular surgery, skull-base surgery, peripheral nerve and complex spinal surgery.[4] Fellowships typically span one to two years. In the U.S., neurosurgery is considered a highly competitive specialty composed of 0.5% of all practicing physicians.[5]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, students must gain entry into medical school. MBBS qualification (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) takes four to six years depending on the student's route. The newly qualified physician must then complete foundation training lasting two years; this is a paid training program in a hospital or clinical setting covering a range of medical specialties including surgery. Junior doctors then apply to enter the neurosurgical pathway. Unlike most other surgical specialties, it currently has its own independent training pathway which takes around eight years (ST1-8); before being able to sit for consultant exams with sufficient amounts of experience and practice behind them. Neurosurgery remains consistently amongst the most competitive medical specialties in which to obtain entry.[6]

History

Neurosurgery, or the premeditated incision into the head for pain relief, has been around for thousands of years, but notable advancements in neurosurgery have only come within the last hundred years.[7]

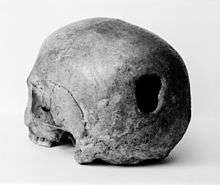

Ancient

The Incas appear to have practiced a procedure known as trepanation since the late Stone Age.[8] During the Middle Ages in Al-Andalus from 936 to 1013 AD, Al-Zahrawi performed surgical treatments of head injuries, skull fractures, spinal injuries, hydrocephalus, subdural effusions and headache.[9]

Modern

There was not much advancement in neurosurgery until late 19th early 20th century, when electrodes were placed on the brain and superficial tumors were removed.

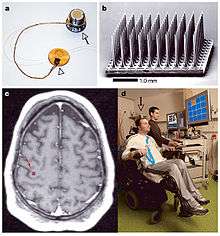

History of electrodes in the brain: In 1878 Richard Canton discovered that electrical signals transmitted through an animal's brain. In 1950 Dr. Jose Delgado invented the first electrode that was implanted in an animal's brain, using it to make it run and change direction. In 1972 the cochlear implant, a neurological prosthetic that allowed deaf people to hear was marketed for commercial use. In 1998 researcher Philip Kennedy implanted the first Brain Computer Interface (BCI) into a human subject.[1]

History of tumor removal: In 1879 after locating it via neurological signs alone, Scottish surgeon William Macewen (1848-1924) performed the first successful brain tumor removal.[3] On November 25, 1884 after English physician Alexander Hughes Bennett (1848-1901) used Macewen's technique to locate it, English surgeon Rickman Godlee (1849-1925) performed the first primary brain tumor removal,[4][10] which differs from Macewen's operation in that Bennett operated on the exposed brain, whereas Macewen operated outside of the "brain proper" via trepanation.[6] On March 16, 1907 Austrian surgeon Hermann Schloffer became the first to successfully remove a pituitary tumor.[11]

Modern surgical instruments

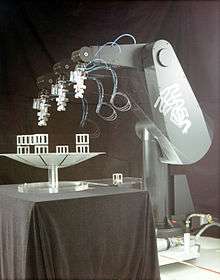

The main advancements in neurosurgery came about as a result of highly crafted tools. Modern neurosurgical tools, or instruments, include chisels, curettes, dissectors, distractors, elevators, forceps, hooks, impactors, probes, suction tubes, power tools, and robots.[12][13] Most of these modern tools, like chisels, elevators, forceps, hooks, impactors, and probes, have been in medical practice for a relatively long time. The main difference of these tools, pre and post advancement in neurosurgery, were the precision in which they were crafted. These tools are crafted with edges that are within a millimeter of desired accuracy.[14] Other tools such as hand held power saws and robots have only recently been commonly used inside of a neurological operating room. As an example, the University of Utah developed a device for computer-aided design / computer-aided manufacturing (CAD-CAM) which uses an image-guided system to define a cutting tool path for a robotic cranial drill.[15]

Organised neurosurgery

The World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS), founded in 1955, in Switzerland, as a professional, scientific, non governmental organization, is composed of 130 member societies: consisting of 5 Continental Associations (AANS, AASNS, CAANS, EANS and FLANC), 6 Affiliate Societies, and 119 National Neurosurgical Societies, representing some 50,000 neurosurgeons worldwide.[16] It has a consultative status in the United Nations. The official Journal of the Organization is World Neurosurgery.[17][18] The other global organisations being the World Academy of Neurological Surgery (WANS) and the World Federation of Skull Base Societies (WFSBS).

Main divisions

General neurosurgery involves most neurosurgical conditions including neuro-trauma and other neuro-emergencies such as intracranial hemorrhage. Most level 1 hospitals have this kind of practice.[19]

Specialized branches have developed to cater to special and difficult conditions. These specialized branches co-exist with general neurosurgery in more sophisticated hospitals. To practice advanced specialization within neurosurgery, additional higher fellowship training of one to two years is expected from the neurosurgeon. Some of these divisions of neurosurgery are:

- Vascular neurosurgery includes clipping of aneurysms and performing carotid endarterectomy (CEA).

- Stereotactic neurosurgery, functional neurosurgery, and epilepsy surgery (the latter includes partial or total corpus callosotomy – severing part or all of the corpus callosum to stop or lessen seizure spread and activity, and the surgical removal of functional, physiological and/or anatomical pieces or divisions of the brain, called epileptic foci, that are operable and that are causing seizures, and also the more radical and very, very rare partial or total lobectomy, or even hemispherectomy – the removal of part or all of one of the lobes, or one of the cerebral hemispheres of the brain; those two procedures, when possible, are also very, very rarely used in oncological neurosurgery or to treat very severe neurological trauma, such as stab or gunshot wounds to the brain)

- Oncological neurosurgery also called neurosurgical oncology; includes pediatric oncological neurosurgery; treatment of benign and malignant central and peripheral nervous system cancers and pre-cancerous lesions in adults and children (including, among others, glioblastoma multiforme and other gliomas, brain stem cancer, astrocytoma, pontine glioma, medulloblastoma, spinal cancer, tumors of the meninges and intracranial spaces, secondary metastases to the brain, spine, and nerves, and peripheral nervous system tumors)

- Skull base surgery

- Spinal neurosurgery

- Peripheral nerve surgery

- Pediatric neurosurgery (for cancer, seizures, bleeding, stroke, cognitive disorders or congenital neurological disorders)

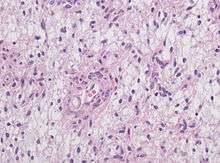

Neuropathology

Neuropathology is a specialty within the study of pathology focused on the disease of the brain, spinal cord, and neural tissue.[20] This includes the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. Tissue analysis comes from either surgical biopsies or post mortem autopsies. Common tissue samples include muscle fibers and nervous tissue.[21] Common applications of neuropathology include studying samples of tissue in patients who have Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, dementia, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, mitochondria disease, and any disorder that has neural deterioration in the brain or spinal cord.[22][23]

History

While pathology has been studied for millennia only within the last few hundred years has medicine focused on a tissue- and organ-based approach to tissue disease. In 1810, Thomas Hodgkin started to look at the damaged tissue for the cause. This was conjoined with the emergence of microscopy and started the current understanding of how the tissue of the human body is studied.[24]

Neuroanesthesia

Neuroanesthesia is a field of anesthesiology which focuses on neurosurgery. Anesthesia is not used during the middle of an "awake" brain surgery. Awake brain surgery is where the patient is conscious for the middle of the procedure and sedated for the beginning and end. This procedure is used when the tumor does not have clear boundaries and the surgeon wants to know if they are invading on critical regions of the brain which involve functions like talking, cognition, vision, and hearing. It will also be conducted for procedures which the surgeon is trying to combat epileptic seizures.[25]

History

Trepanning, an early form of neuroanesthesia, appears to have been practised by the Incas in South America. In these procedures coca leaves and datura plants were used to manage pain as the person had dull primitive tools cut open their skull. In 400 BC the physician Hippocrates made accounts of using different wines to sedate patients while trepanning. In 60 AD Dioscorides, a physician, pharmacologist, and botanist, detailed how mandrake, henbane, opium, and alcohol were used to put patients to sleep during trepanning. In 972 AD two brother surgeons in Paramara, modern-day India, used "samohine" to sedate a patient while removing a small tumor and awoke the patient by pouring onion and vinegar in the patients mouth. Since then, multiple cocktails have been derived in order to sedate a patient during a brain surgery. The most recent form of neuroanesthesia is the combination of carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and nitrogen. This was discovered in the 18th century by Humphry Davy and brought into the operating room by Astley Cooper.[26]

Neurosurgery methods

| Neurosurgery | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10-PCS | 00-01 |

| ICD-9-CM | 01–05 |

| MeSH | D019635 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-01...5-05 |

Neuroradiology methods are used in modern neurosurgery diagnosis and treatment. They include computer assisted imaging computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and stereotactic radiosurgery. Some neurosurgery procedures involve the use of intra-operative MRI and functional MRI.[27]

In conventional open surgery the neurosurgeon opens the skull, creating a large opening to access the brain. Techniques involving smaller openings with the aid of microscopes and endoscopes are now being used as well. Methods that utilize small craniotomies in conjunction with high-clarity microscopic visualization of neural tissue offer excellent results. However, the open methods are still traditionally used in trauma or emergency situations.[11][12]

Microsurgery is utilized in many aspects of neurological surgery. Microvascular techniques are used in EC-IC bypass surgery and in restoration carotid endarterectomy. The clipping of an aneurysm is performed under microscopic vision. minimally-invasive spine surgery utilizes microscopes or endoscopes. Procedures such as microdiscectomy, laminectomy, and artificial disc replacement rely on microsurgery.[13]

Using stereotaxy neurosurgeons can approach a minute target in the brain through a minimal opening. This is used in functional neurosurgery where electrodes are implanted or gene therapy is instituted with high level of accuracy as in the case of Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's disease. Using the combination method of open and stereotactic surgery, intraventricular hemorrhages can potentially be evacuated successfully.[14] Conventional surgery using image guidance technologies is also becoming common and is referred to as surgical navigation, computer-assisted surgery, navigated surgery, stereotactic navigation. Similar to a car or mobile Global Positioning System (GPS), image-guided surgery systems, like Curve Image Guided Surgery and StealthStation, use cameras or electromagnetic fields to capture and relay the patient’s anatomy and the surgeon’s precise movements in relation to the patient, to computer monitors in the operating room. These sophisticated computerized systems are used before and during surgery to help orient the surgeon with three-dimensional images of the patient’s anatomy including the tumor.[28] Real-time functional brain mapping has been employed to identify specific functional regions using electrocorticography (ECoG)[29]

Minimally invasive endoscopic surgery is commonly utilized by neurosurgeons when appropriate. Techniques such as endoscopic endonasal surgery are used in pituitary tumors, craniopharyngiomas, chordomas, and the repair of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Ventricular endoscopy is used in the treatment of intraventricular bleeds, hydrocephalus, colloid cyst and neurocysticercosis. Endonasal endoscopy is at times carried out with neurosurgeons and ENT surgeons working together as a team.

Repair of craniofacial disorders and disturbance of cerebrospinal fluid circulation is done by neurosurgeons who also occasionally team up with maxillofacial and plastic surgeons. Cranioplasty for craniosynostosis is performed by pediatric neurosurgeons with or without plastic surgeons.[30]

Neurosurgeons are involved in stereotactic radiosurgery along with radiation oncologists in tumor and AVM treatment. Radiosurgical methods such as Gamma knife, Cyberknife and Novalis Radiosurgery are used as well.[31]

Endovascular surgical neuroradiology utilize endovascular image guided procedures for the treatment of aneurysms, AVMs, carotid stenosis, strokes, and spinal malformations, and vasospasms. Techniques such as angioplasty, stenting, clot retrieval, embolization, and diagnostic angiography are endovascular procedures.[32]

A common procedure performed in neurosurgery is the placement of ventriculo-peritoneal shunt (VP shunt). In pediatric practice this is often implemented in cases of congenital hydrocephalus. The most common indication for this procedure in adults is normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH).[33]

Neurosurgery of the spine covers the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine. Some indications for spine surgery include spinal cord compression resulting from trauma, arthritis of the spinal discs, or spondylosis. In cervical cord compression, patients may have difficulty with gait, balance issues, and/or numbness and tingling in the hands or feet. Spondylosis is the condition of spinal disc degeneration and arthritis that may compress the spinal canal. This condition can often result in bone-spurring and disc herniation. Power drills and special instruments are often used to correct any compression problems of the spinal canal. Disc herniations of spinal vertebral discs are removed with special rongeurs. This procedure is known as a discectomy. Generally once a disc is removed it is replaced by an implant which will create a bony fusion between vertebral bodies above and below. Instead, a mobile disc could be implanted into the disc space to maintain mobility. This is commonly used in cervical disc surgery. At times instead of disc removal a Laser discectomy could be used to decompress a nerve root. This method is mainly used for lumbar discs. Laminectomy is the removal of the Lamina portion of the vertebrae of the spine in order to make room for the compressed nerve tissue.

Radiology assisted spine surgery uses minimally-invasive procedures. They include the techniques of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty in which certain types of spinal fractures are managed.[34] Potentially unstable spines will need spine fusions. At present these procedures include complex instrumentation. Spine fusions could be performed as open surgery or as minimally invasive surgery. Anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion is a common surgery that is performed for disc disease of cervical spine.[35] However, each method described above may not work in all patients. Therefore, careful selection of patients for each procedure is important. It has to be noted that if there is prior permanent neural tissue damage spinal surgery may not take away the symptoms.

Surgery for chronic pain is a sub-branch of functional neurosurgery. Some of the techniques include implantation of deep brain stimulators, spinal cord stimulators, peripheral stimulators and pain pumps.

Surgery of the peripheral nervous system is also possible, and includes the very common procedures of carpal tunnel decompression and peripheral nerve transposition. Numerous other types of nerve entrapment conditions and other problems with the peripheral nervous system are treated as well.[36]

Conditions

Conditions treated by neurosurgeons include, but are not limited to:[37]

- Meningitis and other central nervous system infections including abscesses

- Spinal disc herniation

- Cervical spinal stenosis and Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Hydrocephalus

- Head trauma (brain hemorrhages, skull fractures, etc.)

- Spinal cord trauma

- Traumatic injuries of peripheral nerves

- Tumors of the spine, spinal cord and peripheral nerves

- Intracerebral hemorrhage, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, interdepartmental, and intracellular hemorrhages

- Some forms of drug-resistant epilepsy

- Some forms of movement disorders (advanced Parkinson's disease, chorea) – this involves the use of specially developed minimally invasive stereotactic techniques (functional, stereotactic neurosurgery) such as ablative surgery and deep brain stimulation surgery

- Intractable pain of cancer or trauma patients and cranial/peripheral nerve pain

- Some forms of intractable psychiatric disorders

- Vascular malformations (i.e., arteriovenous malformations, venous angiomas, cavernous angiomas, capillary telangectasias) of the brain and spinal cord

- Moyamoya disease

Recovery

Post operative pain

Pain following brain surgery can be significant and may lengthen recovery, increase the amount of time a person stays in the hospital following surgery, and increase the risk of complications following surgery.[38] Severe acute pain following brain surgery may also increase the risk of a person developing a chronic post‐craniotomy headache.[38] Approaches to treating pain in adults include treatment with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), which have been shown to reduce pain for up to 24 hours following surgery.[38] Low quality evidence supports the use of the medications dexmedetomidine, pregabalin or gabapentin to reduce post-operative pain.[38] Low quality evidence also supports scalp blocks and scalp infiltration to reduce postoperative pain.[38] Gabapentin or pregabalin may also decrease vomiting and nausea following surgery (very low quality medical evidence).[38]

Notable neurosurgeons

- B. K. Misra - First neurosurgeon in the world to perform image-guided surgery for aneurysms, first in South Asia to perform stereotactic radiosurgery, first in India to perform awake craniotomy and laparoscopic spine surgery.[39]

- Sir Victor Horsley – known as the first neurosurgeon.

- Karin Muraszko – first woman to occupy a chair of neurosurgery at an American medical school (University of Michigan).

- Hermann Schloffer invented transsphenoidal surgery in 1907.

- Harvey Cushing – known as one of the fathers of modern Neurosurgery.

- Robert Wheeler Rand – along with Theodore Kurze, MD was among the first to introduce the surgical microscope into neurosurgical procedures in 1957 and published first textbook on Microneurosurgery in 1969.

- Gazi Yaşargil – known as the father of microneurosurgery.

- Ludvig Puusepp – known as one of the founding fathers of modern neurosurgery, world's first professor of Neurosurgery.

- Walter Dandy – known as one of the founding fathers of modern Neurosurgery.

- Hirotaro Narabayashi – a pioneer of stereotactic Neurosurgery.

- Alim-Louis Benabid – known as one of the developers of deep brain stimulation surgery for movement disorder.

- Wilder Penfield – known as one of the founding fathers of modern neurosurgery, and pioneer of epilepsy Neurosurgery.

- Joseph Ransohoff – known for his pioneering use of medical imaging and catheterization in neurosurgery, and for founding the first neurosurgery intensive care unit.

- Lars Leksell – Swedish neurosurgeon who developed the Gamma Knife.

- Ben Carson – retired pediatric neurosurgeon from Johns Hopkins Hospital, pioneer in hemispherectomy, and pioneer in the separation of craniopagus twins (joined at the head); former 2016 Republican Party presidential candidate, and incumbent United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under the Trump Administration.

- John R. Adler – Stanford University neurosurgeon who invented the CyberKnife.

- Wirginia Maixner – pediatric neurosurgeon at Melbourne's Royal Children's Hospital. Primarily known for separating conjoined Bangladeshi twins, Trishna and Krishna.

- Frank Henderson Mayfield – invented the Mayfield skull clamp.

- Ayub K. Ommaya – invented the Ommaya reservoir.

- Christopher Duntsch - Former neurosurgeon who killed or maimed nearly every patient he operated on before being incarcerated.

- Henry Marsh - leading English neurosurgeon and pioneer of neurosurgical advancements in Ukraine

See also

References

- http://biomed.brown.edu/Courses/BI108/BI108_2005_Groups/03/hist.htm%5B%5D%5B%5D

- "Brain Surgeon: Job Description, Salary, Duties and Requirements". Science. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Preul, Mark C. (2005). "History of brain tumor surgery". Neurosurgical Focus. 18 (4): 1. doi:10.3171/foc.2005.18.4.1.

- Kirkpatrick, Douglas B. (1984). "The first primary brain-tumor operation". Journal of Neurosurgery. 61 (5): 809–13. doi:10.3171/jns.1984.61.5.0809. PMID 6387062.

- "Ensuring an Adequate Neurosurgical Workforce for the 21st Century" (PDF). American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "The Phineas Gage story: Surgery : The University of Akron".

- Wickens, Andrew P. (2014-12-08). A History of the Brain: From Stone Age surgery to modern neuroscience. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781317744825.

- Andrushko, Valerie A.; Verano, John W. (September 2008). "Prehistoric trepanation in the Cuzco region of Peru: A view into an ancient Andean practice". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20836. PMID 18386793.

- Al-Rodhan, N. R.; Fox, J. L. (1986-07-01). "Al-Zahrawi and Arabian neurosurgery, 936-1013 AD". Surgical Neurology. 26 (1): 92–95. doi:10.1016/0090-3019(86)90070-4. ISSN 0090-3019. PMID 3520907.

- "Alexander Hughes Bennett (1848-1901): Rickman John Godlee (1849-1925)". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 24 (3): 169–170. 1974. doi:10.3322/canjclin.24.3.169. PMID 4210862.

- "Cyber Museum of Neurosurgery".

- "Neurosurgery surgical power tool - All medical device manufacturers - Videos".

- "Neurosurgical Instruments,Neurosurgery Instrument, Neurosurgeon, Surgical Tools".

- "Technology increases precision, safety during neurosurgery | Penn State University".

- "Robotics in Neurosurgery". Neurosurgical Focus. 42 (5). 1 May 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- https://www.wfns.org/all-member-societies

- "Journal: World Neurosurgery". WFNS. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "World Neurosurgery, Home page". Elsevier. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Esposito, Thomas J.; Reed, R. Lawrence; Gamelli, Richard L.; Luchette, Fred A. (2005-01-01). "Neurosurgical Coverage: Essential, Desired, or Irrelevant for Good Patient Care and Trauma Center Status". Transactions of the ... Meeting of the American Surgical Association. 123 (3): 67–76. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000179624.50455.db. ISSN 0066-0833. PMC 1357744. PMID 16135922.

- "Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology".

- http://neuropathology.stanford.edu/%5B%5D%5B%5D%5B%5D

- "Dementia".

- Filosto, Massimiliano; Tomelleri, Giuliano; Tonin, Paola; Scarpelli, Mauro; Vattemi, Gaetano; Rizzuto, Nicolò; Padovani, Alessandro; Simonati, Alessandro (2007). "Neuropathology of mitochondrial diseases". Bioscience Reports. 27 (1–3): 23–30. doi:10.1007/s10540-007-9034-3. PMID 17541738.

- van den Tweel, Jan G.; Taylor, Clive R. (2010). "A brief history of pathology". Virchows Archiv. 457 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1007/s00428-010-0934-4. PMC 2895866. PMID 20499087.

- "Awake Brain Surgery (Intraoperative Brain Mapping) | Imaging Services | Johns Hopkins Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring Unit (IONM)".

- Chivukula, Srinivas; Grandhi, Ramesh; Friedlander, Robert M. (2014). "A brief history of early neuroanesthesia". Neurosurgical Focus. 36 (4): E2. doi:10.3171/2014.2.FOCUS13578. PMID 24684332.

- Castillo, Mauricio (2005). Neuroradiology Companion: Methods, Guidelines, and Imaging Fundamentals (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1–428.

- Duan, Zhaoliang & Yuan, Zhi-Yong & Liao, Xiangyun & Si, Weixin & Zhao, Jianhui (2011). "3D Tracking and Positioning of Surgical Instruments in Virtual Surgery Simulation". Journal of Multimedia. 6 (6): 502–509. doi:10.4304/jmm.6.6.502-509.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Swift, James & Coon, William & Guger, Christoph & Brunner, Peter & Bunch, M & Lynch, T & Frawley, T & Ritaccio, Anthony & Schalk, Gerwin (2018). "Passive functional mapping of receptive language areas using electrocorticographic signals". Clinical Neurophysiology. 6 (12): 2517–2524. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2018.09.007. PMC 6414063. PMID 30342252.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Albright, L., Pollack, I., & Adelson, D. (2015), Principles and practice of pediatric neurosurgery (3rd ed.), Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Neuroradiology Patients & Families: Washington University Radiologist".

- Kombogiorgas, D., The cerebrospinal fluid shunts New York: Nova Medical. 2016

- Principles of Neurosurgery- Rengachary, Ellenbogen

- Core Techniques in Operative Neurosurgery - Jandial, McCormick, Black

- Cutts, Steven (January 2007). "Cubital tunnel syndrome". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 83 (975): 28–31. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.047456. ISSN 0032-5473. PMC 2599973. PMID 17267675.

- Greenberg., Mark S. (2010-01-01). Handbook of neurosurgery. Greenberg Graphics. ISBN 9781604063264. OCLC 892183792.

- Galvin, Imelda M.; Levy, Ron; Day, Andrew G.; Gilron, Ian (November 21, 2019). "Pharmacological interventions for the prevention of acute postoperative pain in adults following brain surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011931.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6867906. PMID 31747720.

- http://www.neurosocietyindia.org/site/Past-president/Basant%20Kumar%20Misra,%20President%20NSI%202008.pdf

External links

- The Brain that Changed Everything by Luke Dittrich – Esquire, November 2010

- European Association of Neurosurgical Societies - website

- Mediwikis website - A learning community for medical students