Marshlink line

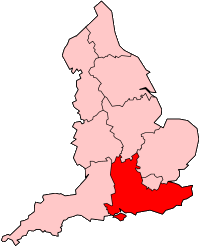

The Marshlink line is a railway line in South East England. It runs from Ashford, Kent via Romney Marsh, Rye and the Ore Tunnel to Hastings where it connects to the East Coastway line towards Eastbourne. Services are provided by Southern.

| Marshlink line | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Two trains stand in the station and passing loop at Rye at the mid point of the single track section of the line | |||

| Overview | |||

| Type | Heavy rail | ||

| System | National Rail | ||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Locale | Kent East Sussex South East England | ||

| Termini | Ashford International Hastings | ||

| Stations | 9 | ||

| Services | Ashford International–Hastings branch line to Dungeness (freight only) | ||

| Operation | |||

| Opened | 13 February 1851 | ||

| Owner | Network Rail | ||

| Operator(s) | Southern | ||

| Character | Rural | ||

| Depot(s) | Ashford International Selhurst | ||

| Rolling stock | Class 171 "Turbostar" (2003–) | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 26 miles 21 chains (42.27 km) | ||

| Number of tracks | 2 (Ashford International–Appledore) 1 (Appledore–Rye) 2 (Passing loop at Rye) 1 (Rye–Ore) 2 (Ore–Hastings) (Branch line to Dungeness also has 1 track) | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | None (Ashford International to Ore) 750 V DC third rail (Ore to Hastings) | ||

| Operating speed | 60 mph (97 km/h) maximum | ||

| |||

Marshlink line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mileage from Charing Cross via South Eastern main line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The line was constructed by the South Eastern Railway (SER) in the late 1840s, and was considered politically important. The SER clashed with the rival London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, leading to disputes over the route, planning and operation. After delays, the line opened in February 1851, followed by branch lines to Rye Harbour in 1854, Dungeness in 1881 and New Romney in 1884. The line struggled to be profitable and it seemed likely that it would close as recommended by the Beeching Report. All branch lines were closed to passengers by 1967 but the main line was kept open because of poor road connections in the area, and the branch to Dungeness remained open for freight. Though the line has been partially single-tracked, and was slow to be modernised, it has survived into the 21st century.

The Marshlink line is one of the few in South East England that has not been electrified, despite regular proposals to do so, and uses the British Rail Class 171 diesel rolling stock. Despite its relative unimportance in the national rail network, it is now considered politically significant as electrification could allow High Speed 1 services to be extended to Hastings and Eastbourne.

Name

The name "Marshlink" was first used in the 1970s by the Southern region of British Rail in an attempt to improve marketing, painting the name on selected rolling stock. The change was one of several in the region, including the "1066 line" from Tunbridge Wells to Hastings.[1]

Route

The line starts at Ashford International, a major interchange in Kent connecting it to High Speed 1 and the South Eastern main line. Services run from Platforms 1 and 2 southwards. Following a brief section of single-track immediately after a branch from the South Eastern main line, the line is then double-track. After 6 1⁄2 miles (10.5 km), it descends on a 1 in 100 (10 ‰) gradient towards Ham Street (previously Ham Street & Orlsetone), crossing the Royal Military Canal and entering Romney Marsh towards Appledore.[2][3][lower-alpha 1] The next 13 miles through Romney Marsh and the Brede Valley are level track, aside from a handful of river crossings.[2]

South of Appledore, a freight-only branch line operated by Direct Rail Services diverges to serve Dungeness nuclear power station. The branch originally served New Romney, Brookland Halt, Lydd Town, Lydd-on-Sea Halt, Greatstone-on-Sea Halt, New Romney and Littlestone-on-Sea and Dungeness.[6][7]

Beyond Appledore, the line is single track and after crossing the River Rother reaches Rye where there is a disused branch to Rye Harbour.[8] The mainline continues to Winchelsea along the Brede Valley, after which it climbs uphill at a 1 in 90 (11.1 ‰).[2] The line passes through the former Snailham Halt (closed in 1959),[9] Doleham and Three Oaks before entering the 1,402-yard (1,282 m) Ore Tunnel.[10]

After the tunnel, the line is double track and electrified (originally for access to the carriage sidings at Ore but since their removal the lines are used by scheduled trains). After Ore, the line enters the 230-yard (210 m) Mount Pleasant Tunnel before a 1 in 60 (16.7 ‰) descent towards Hastings.[2][11]

The Marshlink line does not follow any particular roads.[12] The nearest equivalent route for road transport is the A259 from Hastings to Folkestone via Rye.[13]

Services

Passenger services are operated by Southern.[14] Trains run hourly between Ashford International and Hastings, stopping at Ham Street, Appledore and Rye. Winchelsea and Three Oaks are served by a two-hourly service in each direction (alternating between one and the other), while Doleham is served by just three or four trains per day each way.[15]

Trains then stop at Ore and Hastings before continuing on the East Coastway line; in the past these services usually ran through to Brighton but since May 2018 they form stopping services as far as Eastbourne.[16][17] At peak times, an additional hourly shuttle runs between Ashford and Rye.[18]

Ore station, in addition to Ashford-Eastbourne services, receives services to Brighton and London (hourly to each), which start or terminate there. The services use electric multiple units (usually Class 377s).[19]

Ham Street, Appledore and Rye have staggered platforms: this once allowed passengers to cross the line from the end of one platform to the end of the other.[20][lower-alpha 2] Platforms at Three Oaks and Doleham can only accommodate a single carriage and passengers wishing to alight must travel in one particular carriage of the train.[23]

History

Construction

The line was originally the idea of the Brighton, Lewes and Hastings Railway (BLHR), founded in June 1844 to construct a link between those three towns in association with the London and Brighton Railway (LBR). The South Eastern Railway (SER) wanted to construct a line between Headcorn, Rye and Hastings, but the Parliamentary Select Committee thought there would be insufficient traffic to justify it. After an Act of Parliament was passed to construct the Brighton–Hastings line (now the East Coastway line), the LBR thought it would be useful to extend it further towards Rye and Ashford, which was an area otherwise dominated by SER plans.[24] The SER conducted their own survey from Ashford to Rye in the hope that they would be allowed to construct and own the line instead.[25]

During the 1844–45 Parliamentary session, the Board of Trade decided to approve the BLHR's plans. The SER were unhappy about this arrangement and during the summer of 1845 abandoned their Headcorn–Rye–Hastings scheme, focusing on Hastings–Rye–Ashford instead.[26] The two companies reached a compromise, by which the BLHR were authorised to build the line from Hastings to Ashford, with a caveat that the SER could take over operation if they wished. The proposed line passed through countryside with only Rye as a significant settlement, so the SER easily managed to persuade the BLHR to hand over construction rights.[27]

In June 1846, Parliament deemed that the line was of strategic military importance and ordered that it was to be completed before the extension of the Hastings line from Tunbridge Wells to Hastings.[27][28] As part of the contract, the SER had to pay £10,000 towards refurbishing Rye Harbour, and took responsibility for drainage of the Royal Military Canal which ran close to the line along Romney Marsh.[29]

On 27 July 1846, the LBR and BLHR amalgamated with several other lines to form the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR).[30][31] They became fierce rivals with the SER and complained about a lack of sufficient progress.[27] The SER were unhappy about the proposed line from Rye to Hastings via Ore, which they viewed as too expensive compared to the alternative route via Whatlington. The LB&SCR objected to this route as it was longer, and consequently the SER dropped their proposals that November.[32]

In July 1847, George Robert Stephenson designed a bridge across the Royal Military Canal near Warehorne, while Peter W. Barlow designed a swing bridge over the River Rother at Rye. However, the specific route continued to be debated by the SER throughout early 1848.[33] Work from the Ashford–Rye section started in earnest that summer, making quick progress. The land over Romney Marsh was unstable, and test trains were seen to tip over in heavy winds.[8] The line was planned as single-track, though this was changed to double-track in June 1850.[34]

The line was intended to be opened on 28 October 1850 by Thomas Farncombe, Lord Mayor of London, who inserted the last brick in both the Ore and Mount Pleasant tunnels, but not all work had been completed so the full ceremony was postponed.[34][35] A second proposed opening date of 1 January 1851 was cancelled following signalling problems.[8] The line eventually opened on 13 February 1851, though this was hampered by the rivalries between the companies. The SER blocked LB&SCR trains entering Hastings, not recognising them as the legal successors to the BLH.[36] After a court case the two companies agreed to share the station's facilities for both lines.[37][lower-alpha 3] Even after opening, there were complaints in early 1852 that the line was not completely finished, and it was still marked "nearly complete" in March 1853.[8] The dispute between the SER and the LB&SCR was not fully resolved until 5 December 1870, when the former was allowed to run trains to St Leonards Warrior Square.[39]

The railway opened with four intermediate stations between Ashford and Hastings at Ham Street, Appledore, Rye and Winchelsea.[2] There were almost no other places of significance along the line.[12] Some stations were built a considerable distance away from the settlement they were supposed to serve; for example, Appledore station is around 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the village itself.[40] Four trains per day ran each way on the line, reducing to two on Sundays.[41] Few changes were made to the railway after construction during the 19th century, aside from minor signalling work and some additional buildings.[42] It was not declared profitable by the SER until 1895.[43]

To make money and boost traffic on the line, the SER agreed to hold unlicensed boxing matches on Romney Marsh. On 29 January 1856 a special train ran from London Bridge to Appledore for a prize fight between Tom Sayers and Harry Poulson. Sayers won the fight, which was reportedly rigged by the SER for £1,000. The company was accused of "aiding and abetting a breach of the peace".[44]

Branches from Rye

In 1846, a short branch was proposed from Rye station towards Rye Harbour. It was 3⁄8 mile (0.60 km) long and only used for freight, ending by the River Rother at a pier.[45] The line opened in March 1854.[29] It was almost derelict by 1955, and closed on 29 January 1960.[46][47]

The Rye and Camber Tramway was a separate 3 feet (0.91 m) gauge line the other side of the river. It was proposed in 1895 and funded with a £2,800 capital.[48] A 1 3⁄4-mile (2.8 km) section from Rye to Golf Links Halt opened on 13 July 1895, followed by a 1⁄2-mile (0.80 km) extension to Camber Sands, opening on 13 July 1908. The line was closed in 1939 following competition from bus services and was temporarily part-converted to road during the war. It was returned to railway after hostilities ended, but the line was impractical to repair to full use and hence closed permanently.[49]

Branch to Dungeness and New Romney

.jpg)

The SER had tenuous plans to build a cross-channel passenger ferry terminal at Dungeness, which would provide a dedicated route from London to Paris.[50] In 1859, the Town Clerk of New Romney suggested a line should be built from Folkestone to Rye via Dymchurch and Lydd, but the SER was not interested. However, in 1866 they became favourable about a branch line from Appledore, as it could support their international train proposals. An Act of Parliament to build the line was obtained on 30 July that year, which included a branch to Denge Beach. On 5 August 1873, the SER were authorized to extend the line to Dungeness with a 100-yard (91 m) pier and landing stage. Progress stalled on the line in the 1870s and the SER were in danger of a rival railway taking over construction.[51]

The development of the artillery range at Lydd increased the potential for traffic, so the newly formed Lydd Railway proposed their own bill to work on the Appledore–Lydd branch line. Work began on 8 April 1881 and opened to Dungeness on 7 December that year.[lower-alpha 4] Most trains ran through to Ashford, though a few services terminated at Appledore.[50] An act for the northward branch to New Romney was granted on 24 July 1882, with the line opening on 19 June 1884.[6][40] The line was not a financial success, and the Lydd Railway was absorbed into the SER in 1895.[6]

By the early 20th century, trains were running direct from Charing Cross to New Romney via Ashford and Appledore on summer Sundays.[52] The branch line became important during World War I, when numerous Army camps were established on the shingle wasteland between Lydd and Dungeness. During this time, the line catered for both infantry and horse traffic.[53] A passing loop past Appledore was removed in 1920. At the New Romney end, one of the sidings adjoining the station was extended to serve the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway.[54]

The line was realigned to be closer to the coast in the 1930s, in order to attract holiday traffic along the coast between Dungeness and New Romney. The rerouted line opened on 4 July 1937, and included new stations at Lydd-on-Sea and Greatstone-on-Sea.[55] At the same time, the branch to Dungeness was closed to passengers.[54] By 1952, nine trains a day were serving New Romney from Appledore, with two further through trains from Ashford. After electrification of the South East main line in 1962, the direct services from Charing Cross were discontinued, and the remaining services were run on diesel-electric stock.[56]

Later improvements

Hastings was poorly served by the railway, as many of the residential areas to the east of the town centre were some distance from the station. In 1872, the SER considered building a new station, but progress stalled until July 1886, when a local landowner offered £1,000 (£109,736 in 2019) to build a station near Ore Tunnel. Ore railway station opened on 1 January 1888.[42]

The original swing bridge over the River Rother east of Rye was proposed to be replaced by a fixed bridge in 1881. The SER were amenable to this as the Monk Bretton Bridge (that now carries the A259 east of Rye) was in planning stages, though the replacement bridge did not open until 1903.[57] In 1899, the SER and the London, Chatham and Dover Railway created the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SE&CR) as a joint operation.[58]

In 1907, a steam railcar service was introduced on the line in an attempt to increase local traffic. Three additional halts were constructed between Winchelsea and Hastings; Three Oaks, Guestling (later renamed Doleham) and Snailham, all of which opened on 1 July.[59][60] Snailham Halt was inaccessible by public road, and could only be reached by a rough track. The station was never modernised, and retained its original wooden platforms.[12] Steam railcar services were withdrawn in February 1920 and replaced with tank engines.[61][62] Snailham Halt closed on 2 February 1959.[12][9]

Following World War I, plans were put forward to construct a chord linking the line eastwards at Ashford towards Dover Priory. This would allow trains to run between Hastings and Dover without having to reverse. The plans stalled at the design stage and the link was never constructed.[12]

At the start of 1923, the SER, LCDR and SE&CR amalgamated with other railways to form the Southern Railway following in the Railways Act 1921.[58] The line was electrified from Hastings to Ore in 1935, and electric services began on 7 July. This was done in order that trains could be serviced in a siding away from the centre of Hastings. The siding closed in May 1986.[63] Electrification through to Ashford was planned, but abandoned in 1939 when the war started.[64] It was revived for the Kent electrification scheme Phase 2 of the British Railways Modernisation Plan in the early 1960s, which included some preparatory work such as a footbridge at Rye. The plans were later dropped.[65]

A regular hourly service was introduced in 1959, with additional peak services. This schedule has been largely unchanged.[41]

Threatened closure

The line was recommended for closure by Dr. Richard Beeching in the 1963 Beeching Report as it attracted less than 10,000 passengers a week.[66][67] Like other lines threatened with closure, there was strong opposition, and the route survived because the nearby road network made it impractical to run a replacement bus service.[68] The parallel A259 from Hastings to Brenzett had several level crossings over the line and a hairpin bend at Winchelsea, all of which remain as of the 21st century.[69]

The local member of parliament for Rye, Bryant Godman Irvine made a significant Commons speech complaining about the decision to close the line. As well as the A259, he complained that a lack of rail service would hinder holidaymakers, prevent children from getting to school easily, and remove the potential profitability of being able to move freight via rail.[13] At the same time as the Beeching Report was published, Arthur Irvine complained that a bus took an hour to travel the 19 miles (31 km) between Rye and Ashford.[70] To make a case against closure and save money, the main line was temporarily made single track between Appledore and Ore from June 1965, which lasted until September 1966.[71]

On 23 February 1966, the Ministry of Transport confirmed the branch to New Romney would close to passengers, which it did on 6 March 1967.[7][72] It was kept open for freight as far as a nuclear flask loading and unloading point just outside Dungeness.[73] This branch continues to run a regular service for this purpose, and occasional special passenger trains have been run for rail enthusiasts.[74][75] Shortly afterwards, John Morris, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Ministry of Transport, announced that the remainder of the line was under review and would not close without further advice.[76] The decision to close was delayed several times and dragged on for the remainder of the decade.[77][78] Transport minister Michael Heseltine said a condition of the line closing would be improvements to buses from Ashford to Ore.[79]

In 1969, Railway Magazine announced the remainder of the line would close at the end of the year. In 1971, the Kent Messenger stated the same,[80] as did The Times, which also reported the railway was losing around £130,000 a year.[81] In December 1973, the Ministry of Transport announced that the closure would require review owing to a change in transport policy.[82] On 31 July 1974, the ministry recommended the line for closure but stated that services would run indefinitely for the foreseeable future.[80]

The line was single tracked between Appledore and Ore on 1 October 1979, leaving a passing loop at Rye, in order to reduce maintenance and operational costs. At Winchelsea, the down platform was removed; trains in both directions now stop on the former up platform.[83] Line speed was reduced from 85 mph to 60 mph,[64] but there are additional long term speed restrictions in place, including 40 mph between Doleham and Ore[84] and 20 mph across a half barrier level crossing at Winchelsea.[85] The restrictions mean that services along the Marshlink line do not make optimum use of the rolling stock, which has a top speed of 100 miles per hour (160 km/h).[83]

By the 1980s, British Rail had started to modernise the route,[86] though electrification was rejected in preference to improving the South Eastern main line from Tonbridge to Ashford.[87] After electric services from Tunbridge Wells to Hastings started running on 27 April 1986, the Marshlink line became the only non-electric line in the south east.[64] In January 1992, the Minister for Public Transport, Roger Freeman, announced plans for British Rail to start electrification by 1995.[88]

Privatisation

Following the privatisation of British Rail, the line was operated by Connex South Eastern from 1996, later transferring to Connex South Central.[89][90] After Eurostar services began stopping at Ashford International in 1996, direct services were introduced on the Marshlink line beyond Hastings to Eastborne and Brighton for the first time in 60 years.[91] By 1998, traffic on the line had improved by 20%.[89] In 2000, Southern took over management, and pledged to invest £5 million in improving customer service across its network. However, the Marshlink line continued to attract criticism for its poor service and lack of modernisation; Norman Baker, MP for Lewes described it, after travelling on the Eurostar from Brussels to Ashford International, as "a 1954 diesel train, which shunts along like Thomas the Tank Engine at about 10 mph from Ashford to Hastings."[92]

The line closed for nine weeks from January to March 2012 for essential repair work to Ore tunnel, which was at risk of seeping water. The embankment between Ashford International and Ham Street was repaired, and the bridges next to Doleham and Three Oaks were rebuilt. There was also maintenance to signals to increase train speeds along the line. Network Rail planned to complete the work before patronage increased during the summer.[93][94] The lengthy closure was criticised by MPs whose constituencies the line ran through, who questioned why the entire line had to close in one go as opposed to individual sections at a time.[95]

In May 2018, Southern announced the cancellation of the direct service from Ashford International to Brighton, with Marshlink services only extending to Eastbourne. The company defended the decision as it would improve capacity between Eastbourne and Hastings, but their proposals were criticised by various councillors whose constituencies lay on the route.[96][97]

Listed buildings

The Marshlink line contains several listed buildings along its route, which show architectural or historical merit.

| Location | Grade | Date listed | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) |

Queen's Road Bridge, Hastings | II | 14 September 1976[98] | Constructed in 1898 to replace the original SER road tunnel which restricted traffic.[99] |

|

Rye railway station | II | 11 April 1980[100] | |

|

Gatekeeper's cottage, Rye | II | 22 September 1987 | The cottage is to the northwest of the Rope Walk level crossing, east of Rye railway station[101] |

|

Appledore railway station and goods shed | II | 2 July 2001 | At the time of listing, the main station building had been boarded up and was largely architecturally unchanged since its original 1851 build.[102][103] |

|

Ham Street railway station | II | 9 May 2005[104] | |

| Rye signal box | II | 18 July 2013 | One of only two Saxby & Farmer Type 12 signal boxes still standing (the other is at Wateringbury)[105] |

Accidents and incidents

- Accidents occurring at Ashford and Hastings stations are not covered.

- On 30 April 1852, driver John Hadley was killed at Ham Street station when he went to inspect a locomotive boiler which exploded as he approached it.[44]

- On 27 December 1898, eight passengers were injured when a horse box was roughly shunted and collided with the passenger train it was to be attached to at Appledore.[106]

- On 14 March 1980, an empty stock train comprising five Hastings Unit vehicles derailed at Appledore due to excessive speed through a set of points. The driver was killed. A motor coach was consequently withdrawn from service due to extensive damage.[107]

- On 26 April 1984, a train carrying a nuclear flask on the Dungeness goods branch hit a car on an open level crossing close to Brookland. The line had a speed limit of 5 miles per hour (8.0 km/h) and no damage was done to the flask, though the carrying locomotive was slightly damaged. The occupants of the car did not suffer any serious injuries.[108]

- On 24 January 2019, the Marshlink line was closed after a person was hit by a train. All services between Ashford International and Bexhill were cancelled for part of the day.[109]

Rolling stock

Since the Marshlink line is not electrified, it uses different rolling stock from most of the nearby rail network. The line was originally operated by 4-4-0 locomotives. When the railmotor service was introduced, it used stock from Kitson and Company; following the failure of this service, the line switched to using a variety of tank engines.[110] In 1962, Class 205 "Thumper" and Class 207s diesel units were introduced.[64] Southern planned to withdraw this rolling stock after completing electrification of its remaining diesel lines, but the Strategic Rail Authority rejected the £150 million cost as prohibitive.[111] Instead, the company introduced Class 171 "Turbostar" DMUs in 2003.[64][112]

Concern has been raised that the DMUs will need to be replaced by 2020.[113][114] The diesel-only line prevents other rolling stock being used, including the Class 375 trains used elsewhere on the South East Mainline, and the Class 395 "Javelin" trains on High Speed 1.[115] In the event of a breakdown, the lack of available Class 171s can mean disruption or cancellation of services.[116] The Class 171s are maintained at Southern's depot in Selhurst, some distance away from the line.[69] In November 2017, it was suggested that the line could use British Rail Class 802 electro-diesel multiple unit trains, allowing direct running between HS1 and Hastings. Damian Green, MP for Ashford, endorsed the suggestion as it would allow more services running from St Pancras to Ashford International generally.[117]

Future

The line is strategically important, as electrification and junction improvements would mean that High Speed 1 trains could travel directly from St Pancras International to Hastings.[118] In 2015, Amber Rudd, Member of Parliament for Hastings, campaigned for electrification works to start within the next two years. The aim is to reduce times to London from Hastings to 68 minutes, and from Rye to under an hour.[119][120] This would require remodelling Ashford International station so the existing Marshlink line could connect to HS1, installing power systems, and adding a grade-separated diversion from Rye to the west, all in addition to requiring new trains.[113] An alternative proposal was put forward in 2016 that involved hybrid overhead / battery powered trains, which would not require electrification on the Marshlink line.[121] The two level crossings with the A259 have been criticised as being inadequate, and a decision would be required with the Highways Agency, who manage the road, as to what work is required to make the upgrades go ahead.[122]

The Marshlink Action Group is a volunteer group set up in 2003 in the interests of passengers using the line.[84] The group are concerned about the line's future, particularly the use of Class 171 DMUs. They have reported a high proportion of children and the elderly use the line compared to others in the south east,[69] and that trains are now at capacity but there is no additional stock because of its state as an isolated non-electric line.[123] In 2016, Rudd chaired a working group to look at short and long-term plans for upgrading the Marshlink line, including the potential accommodation of Class 395 rolling stock.[124] A report from Network Rail suggested that third rail electrification would cost around £100–250 million, and overhead electrification would cost between £250 and £500 million.[125]

In May 2018, the Department of Transport allocated £200,000 for further electrification design, with the possibility of completion in 2022 when the existing track life-expires. This could provide the possibility of travelling from Ashford to Hastings in 20 minutes.[126] As of August 2019, Rudd was still promising upgrades to the line in the next five years.[127] In October, a proposal was chaired to build an additional platform at Ashford to support direct St Pancras – Rye services.[128]

Since 2001, there have been proposals to build an additional station at Park Farm, between Ashford International and Ham Street. Following the development of Finberry, a new estate to the southeast of Ashford, the feasibility of a station was re-examined.[129] In December 2018, Ashford Borough Council concluded it was not economically viable or practical to build the station.[130]

References

Notes

- The station's formal name includes (Kent) in its title,[4] although Appledore (Devon) station closed in 1917.[5]

- The last crossing over the line at Ham Street was replaced by a footbridge in 2014 after several accidents.[21][22]

- Because of this rivalry, Hastings station only opened with one through platform. The station was rebuilt in 1931 to allow more services.[38]

- The line was freight-only beyond Lydd; full passenger services to Dungeness opened on 1 April 1883[50]

Citations

- White 1992, p. 211.

- Course 1974, p. 66.

- Bridge 2017, p. 13.

- "Appledore". National Rail Enquires. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Julia Barnes; Maureen Richards; Anthony Barnes (2013). Northam, Westward Ho! & District Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4456-1861-6.

- Gray 1990, p. 228.

- White 1976, p. 100.

- Gray 1990, p. 211.

- Butt 1995, p. 214.

- Body 1984, p. 40.

- Body 1984, p. 106.

- Course 1974, p. 67.

- "How the Rye railway line escaped Dr Beeching's axe". Rye and Battle Observer. 4 April 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- "ESRA comments on new Thameslink/Southern franchise". Rail Technology Magazine. January 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "10 : Hastings to Ashford (timetable)". Southern. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Plans to axe unpopular two-carriage Eastbourne train service". Eastbourne Herald. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Lewes 'losing out' under new rail timetable". Sussex Express. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Train cancellations between Rye and Ashford International". Kent Online. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Southern's Class 377 refurbishment programme completes". Southern Railway News. 25 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Kelly, Peter, ed. (March 1991). "Staggered Platforms". Why & Wherefore. Railway Magazine. Vol. 137 no. 1079. IPC Magazines. p. 221.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "Temporary footbridge for Ham Street station after level crossing incidents". Network Rail Media Centre. 22 September 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Work to improve access for all at Ham Street station in Kent gets under way". Network Rail Media Centre. 16 January 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Letter from Bexhill Rail Action Group to RUS Programme Manager" (PDF). Network Rail. 2009: 6. Retrieved 26 August 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gray 1990, p. 193.

- Gray 1990, p. 194.

- Gray 1990, pp. 194,208.

- Gray 1990, p. 208.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 7.

- Dendy Marshall 1963, p. 290.

- Baldwin 2017, p. 22.

- McCarthy & McCarthy 2007, p. 34.

- Gray 1990, pp. 208–209.

- Gray 1990, p. 209.

- Gray 1990, p. 210.

- "The Ashford, Rye, and Hastings Railway". The Times. 29 October 1850. p. 5. Retrieved 21 October 2019.(subscription required)

- White 1992, pp. 34–35.

- Le Vay 2014, p. 257.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, fig. 1.

- White 1992, p. 35.

- White 1976, p. 97.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Passenger Services.

- Gray 1990, pp. 212–213.

- Gray 1990, p. 214.

- Gray 1990, p. 212.

- White 1976, pp. 137–138.

- White 1976, p. 138,171.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, fig. 40.

- McCarthy & McCarthy 2007, p. 49.

- White 1976, pp. 146–147.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Historical Background.

- Gray 1990, p. 227.

- White 1976, p. 99.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, figs. 67–69.

- White 1976, p. 98.

- McCarthy & McCarthy 2007, pp. 67,68.

- White 1976, pp. 99–100.

- Gray 1990, p. 213.

- McCarthy & McCarthy 2007, p. 66.

- Course 1974, pp. 66–67.

- Butt 1995, pp. 110,214,229.

- Bradley 1980, pp. 32.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, fig. 4.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, fig.6.

- Toynbee, Mark. "A Brief History". Marshlink Action Group. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, fig. 50.

- Beeching 1963, p. 106.

- Beeching 1963, Map 1 & 9.

- "Kent train lines fall victim to Beeching report". Kent Messenger. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Market study response by Marshlink Action Group" (PDF). Network Rail. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- "Railways". Hansard. 30 April 1963. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Hastings–Ashford to be single line". The Times. 30 April 1965. p. 9. Retrieved 21 October 2019.(subscription required)

- "Passenger Services (closures)". Hansard. 21 December 1966. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Course 1974, p. 68.

- Oppitz 2003, p. 82.

- Gammell 1986, p. 25.

- "Ashford-Ore Line (Closure)". Hansard. 5 May 1967. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Ashford–Ore Railway". Hansard. 11 November 1968. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Ashford–Ore Railway". Hansard. 13 October 1969. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Rye-Ashford Area (Public Transport)". Hansard. 26 November 1970. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- White 1976, p. 101.

- "Rail closure plea". The Times. 2 August 1971. p. 2. Retrieved 21 October 2019.(subscription required)

- "Ashford–Ore Railway". Hansard. 5 December 1973. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Network Rail 2016, p. 19.

- "Marshlink future". Rye News. 20 December 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Fig.36.

- "Channel Tunnel Bill". Hansard. 16 February 1987. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Rail Electrification". Hansard. 16 February 1983. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Hastings-Ashford Line". Hansard. 16 January 1992. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Connex consolidates after performance wobbles". Railway Gazette. 1 May 1998. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- South Central Franchise Consultation (PDF). Department for Transport (Report). May 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Mitchell 1996, p. 95.

- Baker, Norman (31 October 2001). "Rail Services (East Sussex)". Hansard. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Ore Tunnel work to close Marshlink rail line". BBC News. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Ashford-to-Hastings rail line closes until March". BBC News. 9 January 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "MPs join forces over Ashford to Hastings rail closure". BBC News. 22 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Plans to axe unpopular two-carriage Eastbourne train service". Eastbourne Herald. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Lewes 'losing out' under new rail timetable". Sussex Express. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Historic England. "Railway Bridge, Queen's Road (1043419)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Queen's Road Bridge (Hastings)". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Rye Railway Station (1252164)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Gatekeeper's Cottage (1252167)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Appledore Railway Station (1245943)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Goods Shed at Appledore Railway Station (1245944)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Hamstreet and Orlestone Railway Station (1391381)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Historic England. "Rye Signal Box (1415163)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Board of Trade. "(Extract for the Accident at Appledore on 26th December 1898)" (PDF). Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 63.

- "Nuclear Waste (Level Crossing Incident)". Hansard. 27 April 1984. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Person hit by train between Ashford International and Bexhill". Kent Online. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Figs.2,4,12.

- Webster, Ben (30 August 2002). ""Nationalised rail network a step closer". The Times. p. 8. Retrieved 21 October 2019.(subscription required)

- "Network Rail Route Plan A 2010" (PDF). Network Rail. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "High speed for Rye is on track". Rye and Battle Observer. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "Reponse to TO Chapter ID 271652". Department for Transport. 14 November 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Network Rail 2016, p. 22.

- "Hastings and Ashford International rail services to be disrupted for hours". Hastings Observer. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "New Hybrid Trains for HS1?". Rail UK. 22 November 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Oppitz 1988, p. 54.

- "Renewed calls for high speed train services at rail summit". Hastings Observer. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "High speed service to run between Ashford and Hastings from London after Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin attends rail summit". Kent Business. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Hybrid trains alternative to electrifying 1066 country railway". Hastings Observer. 18 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- "More Give Than Take on Marshlink". Rye News. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Proposal for Javelin Trains". Marshlink Action Group. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Working group set up to bring high-speed rail to 1066 country". Hastings Observer. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Network Rail 2016, p. 20.

- "Plan for high-speed trains from Ashford to Hastings". Kent Online. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Marshlink Rail upgrade stuck on Amber". Hastings Independent Press. 8 August 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Changes in prospect on Marshlink Train Line". Rye News. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Optimism growing over new train station in Park Farm, Ashford". Kent Online. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Kingsnorth Rail Halt" (PDF). Ashford Borough Council. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

Sources

- Baldwin, James (2017). The Brighton Atlantics. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-473-86938-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beeching, Richard (1963). The Reshaping of British Railways (Report). HMSO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beecroft, Geoffrey (1986). The Hastings Diesels Story. Chessington: Southern Electric Group. ISBN 0-906988-20-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Body, Geoffrey (1984). Railways of the Southern Region. P. Stephens. ISBN 978-0-85059-664-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradley, D.L. (1980). Locomotives of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (2nd ed.). London: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society Press. ISBN 978-0-901-11549-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bridge, Mike (2017). TRACKatlas of Mainland Britain. Platform 5 Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-909-43126-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link))

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Course, Edwin (1974). The Railways of Southern England : Secondary and branch lines. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-2835-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dendy Marshall, C.F. (1963) [1937]. History of the Southern railway. ISBN 0-7110-0059-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gammell, C.J. (1986). Southern Branch lines. G. R. Q. Publications. ISBN 0-946863-0-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Adrian (1990). South Eastern Railway. Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-85-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Vay, Benedict (2014). Britain from the Rails: Including the nation's best-kept-secret railways. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-919-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCarthy, Colin; McCarthy, David (2007). Railways of Britan - Kent and East Sussex. Ian Allen. ISBN 978-0-7110-3222-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1987). South Coast Railways - Hastings to Ashford and the New Romney Branch. Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-37-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic (1996). Ashford - from Steam to Eurostar. Middleton press. ISBN 1-873793-67-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oppitz, Leslie (1988). Kent Railways Remembered. Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-016-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oppitz, Leslie (2003). Lost Railways of Kent. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-803-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, H.P. (1976). Forgotten Railways : Vol 6 – South-East England. David & Charles. ISBN 0-946537-37-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, H.P. (1992) [1961]. Southern England : A Regional history of the railways of Great Britain Vol 2 (5th ed.). David St John Thomas. ISBN 0-946537-77-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kent Route Study Technical Appendix Draft for Consultation (PDF) (Report). Network Rail. December 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

External links

- Route information

- Railfuture article on the Marshlink line

- Hastings to Ashford International – DEMU cab ride – Hastings Diesels Ltd

- Marshlink trains Twitter feed