River Rother, East Sussex

The River Rother flows for 35 miles (56 km) through the English counties of East Sussex and Kent. Its source is near Rotherfield in East Sussex, and its mouth is on Rye Bay, part of the English Channel. Prior to 1287, its mouth was further to the east at New Romney, but it changed its course after a great storm blocked its exit to the sea. It was known as the Limen until the sixteenth century. For the final 14 miles (23 km), the river bed is below the high tide level, and Scots Float sluice is used to control levels. It prevents salt water entering the river system at high tides, and retains water in the river during the summer months to ensure the health of the surrounding marsh habitat. Below the sluice, the river is tidal for 3.7 miles (6.0 km).

| River Rother | |

|---|---|

The Rother near Iden, in the Rother Levels | |

.png) Course of the river Rother. | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mouth | |

• location | Rye Bay |

• coordinates | 50.930913°N 0.771844°E |

The river has been used for navigation since Roman times, and is still navigable by small boats as far as Bodiam Castle. It flowed in a loop around the northern edge of the Isle of Oxney until 1635, when it was diverted along the southern edge. Scots Float Sluice was built before 1723, when the engineer John Reynolds made repairs to it, and later extended it, to try to keep the channel clear of silting, but it was criticised by John Rennie in 1804, as it was inconvenient to shipping. The river became part of a defensive line to protect England from the threat of invasion by the French in the early 1800s, when its lower section and part of the River Brede formed a link between the two halves of the Royal Military Canal. Scots Float Sluice was again rebuilt in 1844. Some 31 square miles (80 km2) of the valley were inundated by floodwater in 1960, which resulted in the Rother Area Drainage Improvement Scheme being implemented between 1966 and 1980. The river banks were raised, and 20 pumping stations were installed.

The river has been managed by a number of bodies, including the Rother Levels Commissioners of Sewers, the Rye Harbour Commissioners, and the Board of Conservators for the River Rother. After the passing of the Land Drainage Act 1930, it was managed by the Rother and Jury's Gut Catchment Board, the Kent River Board, the Kent and Sussex River Authorities, the National Rivers Authority and finally the Environment Agency. It is unusual, in that while it is under the jurisdiction of the Environment Agency, it has been a free river since 1826, and so no licence is required to use it. Management of the levels adjacent to the river is undertaken by the Romney Marshes Area Internal Drainage Board. The Rother passes by or near the villages of Etchingham, Robertsbridge, Bodiam, Northiam, and Wittersham.

Etymology

The modern name of the river is comparatively recent, probably dating from around the sixteenth century. It is derived from the village and hundred of Rotherfield, located where the river rises. Rotherfield means 'open land of the cattle', based on the Old English Hrydera-feld. Prior to being called the Rother, it was known as the Limen throughout its length. This is a Celtic word meaning 'river'. In several Anglo-Saxon charters, it is suffixed with -ea, appearing as Limenea, where the suffix also means 'river', but in Old English.[1] During the thirteenth century, it was known as the River of Newenden.[2]

Hydrology

The Rother rises in the High Weald of Sussex, at around 490 feet (150 m) above ordnance datum (AOD), and descends rapidly. It is joined by the River Dudwell at Etchingham and the River Darwell at Robertsbridge, and by the time it reaches Udiam, it is only 7 feet (2 m) AOD. Average annual rainfall in the High Weald is 35 inches (900 mm), and most of the underlying geology is impermeable, resulting in rain rapidly reaching the river and flowing down to the sea. The river valley is thus prone to winter floods, while during the summer months, the flow can be quite low in dry periods, as there are few groundwater aquifers. Between Udiam and Bodiam, the bed of the river drops below sea level, and the lower river flows slowly. The surrounding land is crossed by networks of canals and ditches, which are pumped into the river during the winter to drain the land. During the summer, water is transferred in the other direction, to manage the habitat of the marshland.[3]

Scots Float sluice, some 3.7 miles (6 km) from the mouth of the river, is used to control levels. It is named after Sir John Scot(t), who enlarged a harbour on the site around 1480.[4] The river below it is tidal, and it is closed as the tide rises, to prevent salt water passing up the river. During dry years, the sluice may be kept closed for most of the summer, as the water is used to maintain the marsh environment. A navigation lock bypasses the sluice. If heavy rainfall coincides with a high tide, where outflow is tide-locked, the river above the sluice to Bodiam acts as a huge holding reservoir for flood water, and is managed as such.[5][6] In times of high flow, water is also pumped from the river at Robertsbridge into Darwell Reservoir,[7] which can hold 167 million cubic feet (4730 Ml) of water.[8][9] It covers an area of 156 acres (63 ha) and was built between 1937 and 1949. Since the 1980s, its output has been taken by pipeline to Beauport Park, from where it provides a public water supply for Hastings.[10]

History

Near its mouth, the River Rother no longer follows its ancient course, as it once flowed across Romney Marsh and joined the sea at Dungeness. It is widely asserted that in 1287 a hurricane, known as the Great Storm, caused large quantities of shingle and mud to be deposited on the port of Romney and the mouth of the river. The water from the river created a new channel, joining the River Brede and the River Tillingham near Rye, where the combined rivers flow into the sea.[11] However, Tatton-Brown has argued that patterns of occupation on Romney Marsh suggest that the change of route took place at least a century before that date.[2] Rye became part of the Cinque Ports in the thirteenth century, and although it is situated some distance from the sea, its harbour is still visited by commercial shipping and has a fleet of fishing boats.[11]

Early developments

The river is known to have been used for shipping in Roman times, when it was navigable to Bodiam and possibly further upstream. There are records of small boats reaching Etchingham during Saxon and Norman periods. Stone for building Bodiam Castle was transported along the river in the fourteenth century, and iron was shipped from Newenden or Udiam in the sixteenth century. A century later, an iron store was erected at Udiam. Maytham Wharf served Rolvenden, while Tenterden was served by Small Hythe.[12]

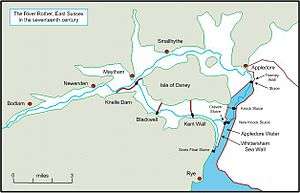

The Isle of Oxney is an area of higher land to the west of Appledore, which is isolated from high ground to its north and south. The valley around the northern edge of it was known as the Upper Levels, while that to the south was called the Wittersham Levels, and had its own Commission of Sewers. The Rother had been routed around the northern side of the Isle since the 1330s, when the Knelle Dam was built at the western end of the Wittersham Levels. The sea was prevented from entering the levels by the Wittersham Sea Wall, built across the eastern end of the valley. This enabled some of the levels to be used for agriculture all year round, although some was only suitable for summer grazing. A perennial problem with the river was that the tides deposited large quantities of silt in the channel, and during the summer months the flow of the river was insufficient to scour the silt away. As a result, some 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) of the Upper Levels were "drowned lands" by 1629, meaning that they were persistently flooded, and another 2,000 acres (810 ha) were only usable in the summer months.[13]

From the 1600s onwards, much effort and expense had been spent trying to drain the Upper Levels, including the construction of the Great Freshwater Sluice below Appledore. Its purpose was to limit the inflow of the tide, and to control the outflow of the river. The works were not particularly successful, and negotiations were started with the Commissioners of the Wittersham Levels to divert the river through those levels. After initial reluctance, an agreement was reached in February 1631. The western end of the levels, from Kent Wall to the Knelle Dam, was to be used as an "indraught", essentially a holding reservoir for river water and some sea water, which would be released in a controlled way to scour the main channel. An embanked channel called the New Salt Channel was constructed across the levels between Kent Wall and a new sluice in the Wittersham Sea Wall. The river was flowing to the south of the Isle by 4 May 1635, an on 4 October, the navigation was also routed along the new channel,[14] reducing its length by 5 miles (8 km). The former channel to the north became known as the Reading Sewer.[15]

Disaster occurred on Lady Day 1644, when an exceptionally high tide flooded the Upper Levels, and broke through the walls of the New Salt Channel. The Commissioners authorised the construction of a new sea sluice at Kent Wall, and work began in May 1646, but in September, they decided that it should be built at Blackwall instead. The height of Knelle Dam was regularly adjusted, in an attempt to manage the amount of water that still flowed along the Appledore Channel, and the conflicting needs of navigation and drainage. The Great Freshwater Sluice below Appledore deteriorated, and failed in 1650. A new sluice with three channels was built in 1669. The financial burden on the Upper Levels as a result of the sea entering the Wittersham Levels was huge, as they had to pay rent on all land that was not available to its original owners,[16] and so in 1671, an agreement was reached that the sea would be excluded from the levels. Work began in 1680 to enclose areas of land on both sides of the valley, and was largely completed by 1684. The work included a new embanked channel for the Rother, which was built along the southern edge of the valley. It was called the Craven Channel, and ended at Craven Sluices.[17]

When repairs to Craven Sluices were necessary in 1684, the water was temporarily diverted into Scots Float Channel. This worked well, and a regulating penn was built, so that water could be routed to Craven Sluices or Scots Float.[18] Knock Sluice was built below the Appledore Sluice in 1686, and land above it was reclaimed.[19] In 1696, New Knock Sluice was built, close to Craven Sluices, and the sea was finally excluded from the Wittersham Levels.[20]

In 1723, the Commissioners of the Kent and Sussex Rother Levels employed the civil engineering contractor John Reynolds to make repairs to Scots Float Sluice, a timber lock on the lower river. He built a dovetailed sheet pile wall below the foundations, and the Commissioners offered him the job of maintaining the levels in 1725, for which he would be paid £65 per year. He moved to Iden and held the post for fourteen years. Silting of the river estuary caused mounting problems with the drainage of the levels during the 1720s. Reynolds carried out further work on the sluice in 1729, and in 1732 reconstructed it to provide an extra outlet. Several new channels were excavated through the levels in the early 1730s, so that all the runoff passed through Scots Float. Reynolds resigned his post in 1739 as he was too busy with other engineering projects.[21]

Navigation

Vessels used on the river were Rye sailing barges, which were about 45 by 12 feet (13.7 by 3.7 m) in size, with a draught of 2.75 feet (0.84 m). A pamphlet published in 1802 announced that there were 16 barges operating on the river, whereas there had only been three some ten years earlier. The main cargoes were manure, fuel and roadstone, and the places served by the river were listed as Appledore, Reading Street, Maytham Wharf, Newenden, Bodiam and Small Hythe. Boats also worked along part of the Newmill Channel towards Tenterden. The river did not have a towing path, and the boats were bow-hauled by men. Scots Float Sluice was described as being "very inconvenient and ill-adapted to the present vessels which navigate the Rother" by the civil engineer John Rennie in 1804.[22]

The end of the eighteenth century was a turbulent period; Britain was at war with France from 1793 to 1802. Hostilities between the two countries ceased with the signing of the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, but in 1803, the Napoleonic Wars began, and there were fears that France would invade England. In order to frustrate such an attack, the Royal Military Canal was proposed. This was initially a small canal near Hythe, but was extended during its planning phase to Cliff End, near Pett in East Sussex.[23] The canal would join the River Rother at Iden and the river would become part of the defence system, as would the course of the River Brede from Rye to Winchelsea. Completion was scheduled for June 1805, but construction did not start until late 1804, and by the time it was completed in 1809, invasion was thought to be unlikely.[24]

The Rother Levels Acts were two Acts of Parliament which were obtained in 1826 and 1830. The Commissioners of the Rother Levels were obliged by the acts to ensure that navigation between Scots Float and Bodiam Bridge was possible, and that all bridges provided at least 5 feet (1.5 m) of headroom. They also enshrined the principle that it was a free river, and no tolls were to be collected for its use. The Rennie brothers, John and George, who had taken over from their father on his death in 1821, produced two reports on the river in 1830, as it was difficult to navigate and prone to flooding. They were critical of the way in which tidal water was allowed to enter the river through Scots Float Sluice, and thought that the river channel was too circuitous, which resulted in shoals forming. The Rennie brothers also criticised the angles at which bridges crossed the channel. William Cubitt and James Elliott rebuilt Scots Float Sluice in 1844.[22]

Iden Lock connected the Royal Military Canal to the river. The last commercial barge to pass from the Rother through Iden lock onto the canal was the Vulture, carrying 27 tons of shingle on 15 December 1909. After that, the lock was replaced by a sluice, severing the navigable connection.[25] The river was used by pleasure craft in Edwardian times, when regular boat trips from Scots Float Sluice, then called Star Lock, to Bodiam Castle were offered. The lower river is currently used for moorings, and the Bodiam Ferry Company operate a trip boat from Newenden Bridge to Bodiam Castle.[11][26]

Flooding

In 1960, there was extensive flooding of the Rother Valley, with some 31 square miles (80 km2) inundated, and in some areas the water did not recede for several months. In 1962 the Kent River Board introduced a bill to Parliament, which would authorise improvements to the river banks, with the construction of a sluice and associated lock below Rye, to prevent tidal flooding. At the time, the river was used by a fishing fleet of at least ten trawlers, and a freighter of 250 tons used the river for a trade in timber. There was some concern in the House of Lords that the lock would not be large enough to accommodate the freighter, although it would be possible to open both sets of lock gates when the tide level was suitable.[27] The bill did not become an Act of Parliament, due to lack of parliamentary time,[28] and so the sluice was not constructed. However, the Rother Area Drainage Improvement Scheme began in 1966, and was completed in 1980. This involved raising the level of the floodbanks along much of the river. Those in the Wet Level, an area of 690 acres (280 ha) between the junction with the Maytham Sewer and Blackwall Bridge, were not raised as much, so that during periods of high flow when the river is tide-locked, the levels can be used for flood storage. The scheme included the installation of 20 pumping stations, which raise water from the low-lying marshes into the embanked river using Archimedes' screw pumps. Some of the drainage ditches in the marshland had to be reconfigured to deliver the water to the pumping stations.[29]

Jurisdiction

River Rother, East Sussex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Responsibility for the river has resided with a number of legal bodies in the past. The first was the Rother Levels Commissioners of Sewers, who were established by letters patent issued under the provisions of the Statute of Sewers dated 1531. The lower river was also covered by the Rye Harbour Commissioners, after they were established by Act of Parliament in 1731. In 1872, the Board of Conservators for the River Rother was created to manage and protect stocks of fish in the river. As in many parts of Britain, the rights and duties of these various bodies competed and overlapped, and by the early twentieth century, the situation was chaotic. An attempt to resolve the confusion was made in 1930, with the passing of the Land Drainage Act 1930, under which 47 catchment areas were established, and a Catchment Board was then created for each one, with overall responsibility for that area. Thus the Rother and Jury's Gut Catchment Board was created. While the board had overall responsibility, local management of rivers and drainage was under the control of Internal Drainage Boards, and the transition was eased by reconstituting Commissioners of Sewers as Internal Drainage Boards, under the terms of the act.[30][31]

The River Board Act of 1950 sought to replace the Catchment Boards with larger organisations, and from 1950 the East Sussex River Board took over the responsibilities of most of the catchments in East Sussex, but the Rother and Jury's Gut Catchment Board became part of the Kent River Board. Further changes followed the Water Resources Act 1963, and responsibility passed to the Kent and Sussex River Authorities in 1964. Ten years later, these structures were replaced by unitary authorities, who had responsibility for the supply of drinking water and for the drainage function of rivers. This lasted until the passing of the Water Act 1989, which split apart the two functions, and management of the river became the responsibility of the National Rivers Authority, Southern Region.[30] Finally in April 1996, the National Rivers Authority was abolished with the formation of the Environment Agency. The agency has responsibility for drainage and water quality, and in the case of some rivers, it holds the navigation rights.[32] The Rother is unusual, in that while it is under the jurisdiction of the Environment Agency, it is a free river, and so a licence is not required to use it. The Environment Agency also acts as the harbour authority for Rye Harbour, another unique situation, and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs acts as a signatory to the Harbour of Rye Bylaws.[11]

The Environment Agency has powers to manage flood control on main rivers, which are defined by a series of statutory main river maps, and for water quality on all watercourses. Responsibility for watercourses other than the main rivers resides with Internal Drainage Boards (IDBs).[33] The Rother is a main river below Mayfield.[34] Internal Drainage Boards have tended to amalgamate to cover larger areas, and the Romney Marshes Area IDB formed from the Romney Marsh Levels, the Walland Marsh, the Denge and Southbrooks, the Rother and the Pett IDBs.[35] It manages 220 miles (350 km) of drainage ditches and watercourses, although most of the pumping stations which pump water from the drainage ditches into the Rother are owned by the Environment Agency.[36]

Route

The River Rother rises from several springs on the south-eastern side of Cottage Hill near Rotherfield in East Sussex. The hill is 653 feet (199 m) above sea level at the top, and the springs are found near the 520-foot (160 m) and 445-foot (136 m) contours. A tributary of the River Medway rises on the north-eastern slopes of the same hill, and flows in the opposite direction. The Rother flows towards the south east, picking up water from other streams, to reach the western edges of Mayfield, where it is crossed by the A267 road.[37] A little before the bridge is the site of Woolbridge Furnace, a scheduled ancient monument.[38]

The river curves to the east along the southern edge of Mayfield, passing a sewage works on the south bank and crossing under an abandoned railway embankment and a road at St Dunstan's Bridge. A tributary joins from the south, which once drove Moat Mill.[37] The mill house dates from the seventeenth century, is timber framed and has been faced with red brick on the ground floor while the attached three-storey mill building dates from the following century. It has been converted into a house, although most of the mill machinery is still present, but has been isolated from the living space by glass panels.[39]

The river is joined by two more tributaries, one from the north and the second from the south, after which it is crossed by a minor road at Scotsford Bridge. It drops below the 148-foot (45 m) contour soon afterwards. The next bridges are Turks Bridge and Bivelham Forge Bridge. Tide Brook joins from the north, and Witherenden Mill, a two-storey building that was originally the mill house is below the junction.[40] In its grounds are two grade II listed oasthouses and a two-storey granary.[41] The railway line, which was following the valley of the Tide Brook, runs parallel to the river as it continues eastwards, passing to the north of Burwash.

After Crowhurst Bridge, which carries the Burwash to Stonegate road over the river, the railway crosses to the south bank. By Etchingham railway station, the River Limden joins from the north, the A265 road crosses, and the River Dudwell joins from the southwest. Both the railway and the river turn to the south to reach Robertsbridge. Another tributary, which flows to the northwest from near a gypsum mine at Brightling, turns to the south and runs parallel to the Rother before joining it in Robertsbridge. There is a network of channels, as the River Darwell joins the river, and there was formerly a mill nearby.[37] The mill was called Hodson's Mill, and was part of Mill Farm. It burnt down in 1902, and the Georgian farmhouse was subsequently demolished. The only original farm building still standing is part of an oasthouse, dating from the late eighteenth century.[42]

A little further to the east, the grade I listed Abbot's House from the former Cistercian Abbey at Robertsbridge stands on the south side of the river. The Abbey was founded by Alured and Alicia de St Martin in 1176, although the house was probably built between 1225 and 1250. It was modified in the 1530s by Sir William Sydney, and again in the nineteenth century. An attic bedroom had a wooden fireplace dating from the 1830s, but surrounded by medieval tiles described by the National Heritage List as being of "superlative quality."[43] There are additional ruins near Abbey Farmhouse.[44]

The river turns towards the northeast, passing under an abandoned railway bridge and dropping below the 16-foot (4.9 m) contour to reach Bodiam. A local road crosses the river at Bodiam Bridge, and passes through the site of a Romano-British settlement to the south of the bridge.[45]

Navigable section

Beyond the bridge is Bodiam railway station, the western terminus of the Kent and East Sussex Railway since 2000. On the north bank of the river is Bodiam Castle, built soon after 1385 by Sir Edward Dalyngrigge. Lord Curzon restored the ruins in 1919 and gave them to the National Trust six years later. The buildings are grade I listed,[46] and the landscaped grounds, which include a millpond and a Second World War pillbox, are a scheduled ancient monument.[47]

For the final 14 miles (23 km) from Bodiam to the sea, the bed of the river is below the high-water mark of neap tides,[48] and there are numerous drainage ditches traversing the valley floor. The river is embanked, with sluices and pumping stations along its banks, which discharge water drained from the low-lying land into the river channel. The Kent Ditch joins on the northern bank, and forms the boundary between the counties of Kent and East Sussex. After the junction, the boundary runs along the centre of the river.

At Newenden, Newenden Bridge carries the A28 road over the channel. It was built with three arches in 1706, but in an earlier Medieval style.[49] Northiam lies just to the south. A loop to the south takes the river under the Kent and East Sussex Railway, and into an area known as the Rother Levels. The county boundary now follows a small channel to the north, which was the main channel when the river passed around the northern edge of the Isle on Oxney prior to 1635. The boundary joins the Hexden Channel near Maytham Wharf, and rejoins the river when the channel does. Next, Potman's Heath Channel joins.

The short channel splits into Newmill Channel and Reading Sewer a little further to the north, the first flowing southwards, and the second originally flowing northwards, when it was the main channel for the River Rother. A public footpath follows the eastern bank of Potman's Heath Channel, and continues along the north bank of the river to Blackwall Bridge, where it becomes part of the Sussex Border Path,[37] a long-distance footpath that follows the county boundary.[50]

The low-lying land through which the channel passes is called the Rother Levels. Soon after New Bridge carries Wittersham Road over the river, the channel turns to the south, to run along the eastern edge of Walland Marsh. The Military Road, which was built along the landward side of the Royal Military Canal, crosses to the western bank of the river just before Iden Lock, the disused entrance to the canal. The lock structure contains a sluice mechanism, which is used to regulate water levels in the canal, but during the summer months, water is pumped from the river into the canal, from where it irrigates the marshes.[51][52]

The Military Road continues to follow the west bank, while the Saxon Shore Way footpath follows the eastern bank. Next comes Scots Float Lock, below which the river is tidal. As it approaches the eastern edge of Rye,[37] it is crossed by a fixed truss bridge which carries the Marshlink railway line. The bridge was installed in 1903, and replaced a swing bridge erected in 1851 during the construction of the railway, which opened in 1852.[53] Monk Bretton Bridge carries the A259 New Road, and below that, the Rother is joined by the River Brede at the southern edge of Rye. The river channel is quite wide, and is known as Rye Harbour. There is also a village called Rye Harbour, at the southern end of the wide section.[37]

There was a wharf on the river in 1874, served by a railway line, and sidings which were used to collect shingle. By 1909, the wharf had been replaced by a landing stage slightly further downstream, which was also served by the railway.[54] As it nears the sea, a Martello tower, built in 1806 to protect against French invasion, stands to the west of the channel. It is numbered 28, and was one of many such structures built at the time.[55] Nearby is an Inshore Rescue station, run by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution[56] The river then enters Rye Bay, part of the English Channel.[37]

Water quality

The Environment Agency measure the water quality of the river systems in England. Each is given an overall ecological status, which may be one of five levels: high, good, moderate, poor and bad. There are several components that are used to determine this, including biological status, which looks at the quantity and varieties of invertebrates, angiosperms and fish, and chemical status, which compares the concentrations of various chemicals against known safe concentrations. Chemical status is rated good or fail.[57]

The water quality of the River Rother system was as follows in 2016.

| Section | Ecological Status | Chemical Status | Overall Status | Length | Catchment | Channel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Rother Five Ashes to Coggins Mill Stream[58] | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | 10.8 miles (17.4 km) | 15.04 square miles (39.0 km2) | |

| Rother between Coggins Mill Stream and Etchingham[59] | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | 7.3 miles (11.7 km) | 9.09 square miles (23.5 km2) | |

| Socknersh Stream[60] | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | 5.7 miles (9.2 km) | 3.92 square miles (10.2 km2) | |

| Limden[61] | style="background: #ffd784; text-align: center;" | Poor | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffd784; text-align: center;" | Poor | 4.0 miles (6.4 km) | 6.77 square miles (17.5 km2) | |

| Kent Ditch[62] | style="background: #ffd784; text-align: center;" | Poor | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffd784; text-align: center;" | Poor | 9.9 miles (15.9 km) | 10.84 square miles (28.1 km2) | |

| Hexden Channel[63] | style="background: #ffd784; text-align: center;" | Poor | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffd784; text-align: center;" | Poor | 15.9 miles (25.6 km) | 20.10 square miles (52.1 km2) | |

| Lower Rother from Etchingham to Scott's Float[64] | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | 30.2 miles (48.6 km) | 55.51 square miles (143.8 km2) | heavily modified |

| Rother[65] | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | style="background: #7af58a; text-align: center;" | Good | style="background: #ffff99; text-align: center;" | Moderate | heavily modified |

The reasons for the quality being less than good include sewage discharge affecting most of the river, and physical modification of the lower river.

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes

a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source near Rotherfield | 51.0362°N 0.2202°E | TQ557286 | One of several |

| A267 Bridge, Mayfield | 51.0141°N 0.2437°E | TQ574262 | |

| Turks Bridge | 51.0098°N 0.3226°E | TQ630259 | |

| Junction with Seller's Brook | 51.0097°N 0.3794°E | TQ670260 | |

| Etchingham Railway Bridge | 51.0137°N 0.4233°E | TQ700266 | |

| Junction with River Limden | 51.0112°N 0.4440°E | TQ715263 | |

| Junction with Glottenham Stream | 50.9889°N 0.4821°E | TQ742239 | Robertsbridge |

| Bodiam Bridge | 50.9996°N 0.5399°E | TQ783253 | Limit of navigation |

| Junction with Kent Ditch | 51.0034°N 0.5715°E | TQ805258 | |

| Maytham Wharf | 51.0178°N 0.6614°E | TQ867276 | now on Hexden Channel |

| Iden Lock, Royal Military Canal | 50.9866°N 0.7574°E | TQ936244 | |

| Scots Float Lock | 50.9699°N 0.7508°E | TQ932225 | |

| Junction with River Brede | 50.9498°N 0.7394°E | TQ925202 | Rye |

| Mouth into Rye Bay | 50.9280°N 0.7746°E | TQ950179 | English Channel |

Bibliography

- Blair, John, ed. (25 October 2007). Waterways and Canal-Building in Medieval England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921715-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- CAMS (2006). "The Rother Catchment Abstraction Management Strategy" (PDF). Environment Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- CFMP (2008). "The Rother and Romney Catchment Flood Management Plan (Part 2)" (PDF). Environment Agency.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- CMP (May 1994). "East Sussex Rother Catchment Management Plan Consultation Report" (PDF). National Rivers Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2009). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (8th Ed.). Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-1-84623-010-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dobson, Alban; Hull, Hubert (1931). The Land Drainage Act 1930. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eddison, Jill (1988). 'Drowned Lands': Changes in the Course of the Rother and its Estuary and Associated Drainage Problems, 1635-1737. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Chapter 12 of Eddison & Green 1988)

- Eddison, Jill; Green, Christopher, eds. (1988). "Romney Marsh: Evolution, Occupation, Reclamation". Monograph 24. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. ISBN 978-0-947816-24-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadfield, Charles (1969). The Canals of South and South-East England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-4693-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Godfrey (1988). Sea defence and land drainage of Romney Marsh. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Chapter 13 of Eddison & Green 1988)

- Skempton, Sir Alec; et al. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 1: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-2939-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tatton-Brown, Tim (1988). The Topography of the Walland Marsh area between the 11th and 13th centuries. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Chapter 9 of Eddison & Green 1988)

References

- Tatton-Brown 1988, pp. 95-96.

- Tatton-Brown 1988, p. 105

- CFMP 2008, pp. 27, 29.

- Blair 2007, pp. 100–104.

- CMP 1994, pp. 3-4.

- CFMP 2008, p. 29.

- CMP 1994, p. 12.

- "Reservoir Levels". Southern Water. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- CFMP 2008, p. 33.

- "Darwell Reservoir". Mountfield Parish Council. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Cumberlidge 2009, p. 260

- Hadfield 1969, pp. 34, 37.

- Eddison 1988, p. 142.

- Eddison 1988, pp. 142-145.

- Hadfield 1969, p. 37.

- Eddison 1988, p. 146.

- Eddison 1988, pp. 147-148.

- Eddison 1988, pp. 148-149.

- Eddison 1988, p. 150.

- Eddison 1988, p. 152.

- Skempton 2002, p. 571.

- Hadfield 1969, p. 37

- Hadfield 1969, pp. 38-39.

- Cumberlidge 2009, p. 261.

- Hadfield 1969, p. 42.

- "Boat Trips on the River Rother". Bodiam Ferry Company. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- "Kent River Board (Harbour of Rye) Bill". Hansard. SS.1074,1080. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "What is RHBOA?". Rye Harbour Boat Owners Association. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- Robinson 1988, p. 166.

- "Archive of the National Rivers Authority, Southern Regions". The National Archive. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- Dobson & Hull 1931, p. 113.

- Cumberlidge 2009, p. 40.

- "Explanation of Terms". Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- CAMS 2006, p. 3.

- "Welcome to... Romney Marshes". Romney Marshes Area IDB. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Maintenance". Romney Marshes Area IDB. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- Ordnance Survey, 1:25,000 map, available here

- Historic England. "Woolbridge Furnace (1002209)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Moat Mill House and Mill (1286040)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Witherenden Mill (1274562)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Roundels oasthouses and granary (1237651)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Former oasthouse to Mill Farm (1391400)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Historic England. "The Abbey, Robertsbridge (1221354)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Abbey ruins, Robertsbridge (1274121)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Romano-British site south of Bodiam Bridge (1002235)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Bodiam Castle (1044134)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Bodiam Castle and its landscaped setting (1013554)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Eddison & Green 1988, p. 142.

- Historic England. "Newenden Bridge (1217121)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Sussex Border Path". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- CFMP 2008, p. 32.

- CMP 1994, p. 4.

- "Rye's Harbour in the 19th Century". Rye Castle Museum. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1874 and 1909

- Historic England. "Martello Tower (1217121)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Rye Harbour Lifeboat Station". RNLI. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Glossary (see Biological quality element; Chemical status; and Ecological status)". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- "Upper Rother Five Ashes to Coggins Mill Stream". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Rother between Coggins Mill Stream and Etchingham". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Socknersh Stream". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Limden". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Kent Ditch". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Hexden Channel". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Lower Rother from Etchingham to Scott's Float". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Rother". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

External links

![]()