Mareth Line

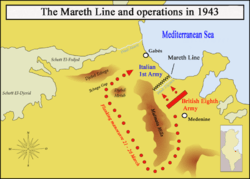

The Mareth Line was a system of fortifications built by France in southern Tunisia in the late 1930s. The line was intended to protect Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya. The line occupied a point where the routes into Tunisia from the south converged, leading toward Mareth, with the Mediterranean Sea to the east and mountains and a sand sea to the west.

| Mareth Line | |

|---|---|

| Part of French defence of Tunisia | |

| Tunisia | |

Mareth Line in 1943 | |

| Coordinates | 33°38′00″N 10°18′00″E |

| Height | 2,200 feet (670 m) |

| Length | 25 miles (40 km) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | French colonial administration of Tunisia |

| Operator | French army (1939–1940) |

| Controlled by | German–Italian Panzer Army (Deutsch-Italienische Panzerarmee/Armata Corazzata Italo-Tedesca) [1943] |

| Condition | Derelict |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1936 |

| Built by | French colonial administration of Tunisia and French Army |

| In use | March 1943 |

| Materials | reinforced concrete |

| Fate | Abandoned after 1943 |

| Battles/wars | Battle of the Mareth Line |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Erwin Rommel |

| Garrison | 1943, east to west: 136th Infantry Division Giovani Fascisti, 101st Motorised Division Trieste, 90th Light Division, 80th Infantry Division La Spezia, 16th Motorised Division Pistoia, 164th Light Afrika Division 15th Panzer Division (32 operational tanks) Reserve: 21st Panzer Division, 10th Panzer Division (110 operational tanks); Djebel Tebaga to Djebel Melab: Raggruppamento Sahariano |

The line ran along the north side of Wadi Zigzaou for about 50 km (31 mi) south-westwards from the Gulf of Gabès to Cheguimi and the Djebel (mountain) Matmata on the Dahar plateau between the Grand Erg Oriental (Great Eastern Sand Sea) and the Matmata hills. The Tebaga Gap, between the Mareth line and the Great Eastern Sand Sea, a potential route by which an invader could outflank the Mareth line, was not surveyed until 1938.

After the French Armistice of 22 June 1940, the Mareth Line was demilitarised under the supervision of an Italo-German commission. Tunisia was occupied by Axis forces after Operation Torch in 1942 and the line was refurbished and extended by Axis engineers into a defensive position by building more defences between the line and Wadi Zeuss 3.5 mi (5.6 km) to the south but French-built anti-tank gun positions were too small for Axis anti-tank guns which had to be sited elsewhere.

The Battle of Medenine (6 March 1943) against the Eighth Army was a costly failure. At the Battle of the Mareth Line (16–31 March 1943) the Eighth Army was contained within the Mareth Line defences. An outflanking move west and north of the Mareth Line was followed by Operation Supercharge II which broke through the Axis defences of the Tebaga Gap and led them to retreat from the Mareth Line to Wadi Akarit. The Mareth Line is derelict and is commemorated at the Mareth Museum.

Background

French strategy

In the 1930s the defence of the French colonial empire (French Indochina, Pacific Islands, West Indies, African colonies and Syria–Lebanon) was left to the French Foreign Legion, colonial and "native" units, the Marine nationale (Navy) and the Armée de l'Air (Air Force). By the late 1930s, the Navy had only one aircraft carrier and the Armée de l'Air could spare only second-rate aircraft. Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia provided much of the manpower of the Armée coloniale and Tunisia, with the Italian colony of Libya to the east, was excepted from the priority given to the defence of metropolitan France.[1] French plans for defence of Tunisia assumed that Italy would launch an overwhelming assault that France could not easily oppose. Italy was expected to launch attacks on Egypt and Tunisia as soon as war was declared, with the Italian Navy securing supply and blocking any substantial Anglo-French relief. With a force of six divisions, a fortress division and a cavalry division to defend Tunisia, capable of only local operations with limited objectives. The French army considered the construction of a "Maginot Line in the desert" (ligne Maginot du désert).[2][lower-alpha 1]

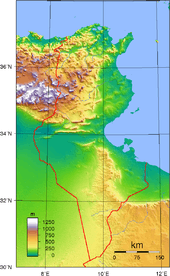

Geography

Central Tunisia is dominated by the Atlas Mountains, while the northern and southern portions are largely flat. The primary feature in the south is the Matmata Hills, a range running north-south roughly parallel to the Mediterranean coast. West of the hills, the land is the inhospitable Jebel Dahar and the Dehar region of desert beyond to the west, making the region between the hills and the coast the only easily traversed approach to northern Tunisia.[4] A smaller line of hills runs east–west along the northern edge of the Matmata range, further complicating this approach. At the far northern end of the Matmata Hills is the Tebaga Gap. From the Mediterranean the coastal plain rises gently to the Matmata Hills. The plain consists of gravels and sands, with salt flats between the sandy areas, which turn into bogs after light rain becoming impassable to wheeled vehicles. There are numerous wadis from the hills to the sea, including the bigger Wadi Zeuss and Wadi Zigzaou. Inland, the sources of the whe wadis are steep and rocky, widening near the coast, the beds having streams or muddy bottoms, with firmer areas traversable by vehicles.[5]

Plans

In January 1934 planning began on the new fortifications; Infantry officers selected the sites for strongpoints to dominate the ground in front with overlapping fields of fire. In 1936, the French government provided funds for construction after Italy formed the Rome–Berlin Axis with Germany, creating a greater threat to French security in North Africa.[6][lower-alpha 2] The casemates designed for the line had much less concrete than comparable examples in France and had no fossé (gap) rather a stable door, in case the lower part was blocked by débris. In September 1936, during a meeting with General Joseph Georges, it was agreed that the fortification of the Mareth Line, Bizerte, Medenine, Ben Gardane and Foum Tataouine (Tataouine) must be completed. Medenine, Ben Gardane to the west and Tataouine to the east, were south of the proposed line, Tataouine being the place where the routes to Mareth passed through the bottleneck between the Matmata Mountains and the sea.[6]

The line was divided into eastern and western sectors with a main line of resistance and a reserve line about 0.93 mi (1.5 km) back. A secteur défensif (SD) was to be built on the rocky Dahar Plateau, which later became part of an SD across the Matmata Hills to Kebili on the edge of the Chott el Djerid. The chott and Chott El Fedjaj drained across Tunisia into Wadi Akarit, across Tunisia but Wadi Akarit was only sketchily fortified, the French concentrating on the Mareth Line 31 mi (50 km) south, to cover Gabes.[6] The gap between the Mareth Line and the Great Eastern Sand Sea, a potential route by which an invader could outflank the Mareth line, was not given consideration until 1938. General Georges Catroux and Colonel Gautsch surveyed the area and in their assessment predicted that three divisions could advance from the Libyan border to Ksar (fortified village) el Hallouf and Bir (well) Soltane in six days and then advance into the gaps either side of Djebel Melab and those between Djebel Tebaga and the Matmata Hills. [7]

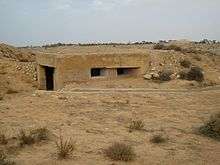

Mareth Line

The Mareth Line consisted of casemates surrounded by barbed wire and built for all-round defence in the main and reserve lines, the obstacles being doubled on the fronts and sides. The strongpoints in the main line included flanking machine-gun casemates and anti-tank gun positions; in the reserve line artillery emplacements provided covering fire in the gaps between the strongpoints in the main line. Some of the flanking casemates for machine-guns covering the gaps were connected by galleries; strongpoints on the plain and in hills had anti-tank positions. An anti-tank obstacle of vertical rails was built along the front of the line and the sides of Wadi Zigzaou were steepened. Eight artillery casemates, forty infantry casemates or blockhouses and fifteen command posts were built. The eastern sector had twelve strongpoints in the main line and eleven in the reserve line. The western sector had eleven strongpoints in the main line and seven in the reserve line.[6]

In the Matmata hills, Ksar el Hallouf covered an anti-tank ditch which continued the position beyond the main line which ended on the foothills. An infantry position was dug into the Matmata hills at Ksar-el-Hallouf and in the Dahar beyond, a strongpoint at Bir Soltane had two 75 mm turrets, removed from Char 2C tanks built in 1918. At Ben Gardane an advanced position was built consisting of a square redoubt inside an anti-tank ditch with casemates on the flanks and concrete infantry shelters. Small triangular strongpoints at the corners were surrounded by anti-tank rail obstacles that continued around the position. The Mareth line was equipped with obsolescent 75 mm and 47 mm naval guns for anti-tank defence and a few new 25 mm anti-tank guns and infantry small arms. The artillery casemates with 75 mm guns and most of the blockhouses and casemates had embrasures for automatic weapons. In 1938 work the Mareth line was so important that work on coast defences was stopped and in 1939 the line was occupied by colonial divisions and some locally raised units. After the outbreak of the war, a line of advanced positions (avant-postes) was built on high ground at Aram 6.2 mi (10 km) south of the main line.[6]

Second World War

Demilitarisation 1940, Axis occupation 1943

The Second World War began in 1939 but the Mareth Line was inactive from 1939 to 1940, as Italy remained neutral until a few days before the Armistice of 22 June 1940, after which, the line was demilitarised by an Italo-German commission. In November 1942, the British Eighth Army (General Bernard Montgomery) defeated Panzerarmee Afrika at the Second Battle of El Alamein and the British First Army landed in French North Africa in Operation Torch. Axis forces occupied Tunisia in the Tunisia Campaign and from November 1942 to March 1943, the Panzerarmee conducted a fighting retreat through Egypt and Libya, pursued by the Eighth Army. In March the Eighth Army reached the Libya–Tunisia border and paused at Medenine to prepare to attack the Mareth Line. Axis engineers built an outpost zone from Wadi Zeuss 3.5 mi (5.6 km) back to the Mareth Line. Field fortifications were constructed at Sidi el Guelaa, south of Aram on the main road from Medinine to Mareth, around Aram and at Bahira. The Mareth Line was refurbished for occupation by the Panzerarmee and by March 1943, more than 62 miles (100 km) of barbed wire, 100,000 anti-tank mines and 70,000 anti-personnel mines had been laid, bunkers had been reinforced with concrete and armed with anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns.[8]

Medenine and Mareth

The Axis forces opposing the Eighth Army were renamed the Italian 1st Army (General Giovanni Messe) on 23 February 1943 and attempted a spoiling attack, the Battle of Medenine (Unternehmen Capri, Operation Capri). The attack was a costly failure and the Axis troops withdrew to the Mareth Line to await the British attack.[9] The Mareth Line was garrisoned by the 136th Infantry Division "Giovani Fascisti" from the coast to Zarat, the 101st Motorised Division "Trieste" covering the Gabès–Mareth road around Mareth and Aram, the 90th Light Division to the south of the "Trieste" Division at Aram and Sidi el Guelaa cutting the road and covering Wadi Zeuss, 80th Infantry Division "La Spezia" south of the 90th Light Division, the 16th Motorised Division "Pistoia" south of "La Spezia", near Beni Kreddache covering the Hallouf Pass the line was held by the 164th Light Afrika Division. The 15th Panzer Division with 32 operational tanks was based at Zerkine 5 mi (8.0 km) north-west of Mareth. In reserve were the 21st Panzer Division south-west of Gabès and the 10th Panzer Division south-west of Sousse with 110 operational tanks. The line from Djebel Tebaga to Djebel Melab was held by the Raggruppamento Sahariano.[10][lower-alpha 3] The British survey of the Mareth Line, the positions of Zarat sudest (Zaret South-West), Ouerzi, Ouerzi Ouest (Ouerzi West), Ouerzi Est (Ouerzi East), Ksiba Ouest and Ksiba Est being of particular interest, was assisted by General Marcel Rime-Bruneau, a former Chief of Staff of the Tunisian garrison and Captain Paul Mezan, the former Garrison Engineer of the Mareth Line.[5]

Battle of the Mareth Line

On 19 March 1943, the Eighth Army made a frontal assault against the Mareth Line in Operation Pugilist. The 50th Northumbrian Infantry Division penetrated the Line near Zarat but was driven back by the 15th Panzer Division and the"Giovani Fascisti" on 22 March.[11] Reconnaissance by the Long Range Desert Group had shown that the line could be outflanked. A force could pass through the southern Matmata Hills, reach the Tebaga Gap from the west and reach the coastal plain behind the Mareth Line. During Pugilist, Montgomery had sent the 2nd New Zealand Division around the Matmata Hills but its attack was contained at the Tebaga Gap from 21 to 24 March. Montgomery sent the 1st Armoured Division (X Corps) to reinforce the attack at the Tebaga Gap. The British attacked again in Operation Supercharge II on 26 March and broke through the gap the next day. This success, combined with another frontal assault on the Mareth Line, made the position untenable; the Italian 1st Army escaped encirclement when the 1st Armoured Division was held up at El Hamma and the Axis forces retreated to Wadi Akarit, 37 miles (60 km) to the north.[12]

Post war

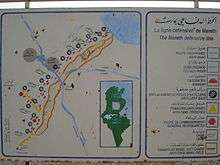

After the Battle of the Mareth Line, the defences were left to become derelict and are commemorated at the Mareth Museum at Gabès.[13]

Notes

- Two of the infantry divisions were transferred to France from 21 May 1940 and by 7 June the French force had been reduced to four infantry divisions, fortress troops and local cavalry.[3]

- The cost of the Mareth Line and its forward defences was similar to that of Ouvrage Sainte-Agnès in the Alps.[6]

- The Raggruppamento Sahariano consisted of two battalions of Infantry Regiment 350, three companies of the Novara Group, a Frontier Guard battalion, a battalion from the "Savona" Division, a machine-gun battalion, four Saharan companies and nine troops of artillery.[10]

Footnotes

- Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2006, p. 89; Jackson 2000, pp. 332–333.

- Playfair 1954, pp. 92–93.

- Knox 2004, p. 120.

- Ford 2012, p. 46.

- Playfair 2004, p. 332.

- Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2006, p. 90.

- Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2006, p. 89; Playfair 2004, p. 333.

- Playfair 2004, p. 334.

- Playfair 2004, p. 324.

- Playfair 2004, p. 333.

- Playfair 2004, pp. 362–363.

- Playfair 2004, pp. 337–351.

- TT 2020.

References

- Dear, I. C. B., ed. (2001). The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860446-7.

- Ford, K. (2012). The Mareth Line 1943: The End in Africa. Steve Noon (ebook ed.). Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78096-094-4.

- Jackson, P. (2000). France and the Nazi Menace: Intelligence and Policy Making, 1933–1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19820-834-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaufmann, J. E.; Kaufmann, H. W. (2006). Fortress France: The Maginot Line and French Defenses in World War II (online scan ed.). Westport, CT: Praeger Security International (Greenwood Publishing). ISBN 0-275-98345-5.

- Knox, MacGregor (2004) [1982]. Mussolini Unleashed 1939–1941 Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War (repr. pbk. ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33835-2 – via online scan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (1954). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. I (4th impr. ed.). HMSO. ISBN 1-84574-065-3.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004) [1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. IV (pbk. facs repr. Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 1-84574-068-8.

- Prior-Palmer, Brigadier G. E. (March 1946). "II, Medenine to Tunis". A Short History of the 8th Armoured Brigade. no isbn. Hanover: H.Q. 8th Armoured Brigade. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- "Travel Tips Tunisia: Visit 4 World War II Sites in Tunisia". mosaicnorthafrica com. 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

Further reading

- Gauché, Maurice (1953). Le Deuxième Bureau au Travail, 1935–1940 [The Deuxième Bureau at Work]. Archives d'histoire contemporaine (in French). Paris: Amiot Dumont. OCLC 3093195.

- Stevens, Major-General W. G. (1962). "8–10". Bardia to Enfidaville. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. Wellington, NZ: Historical Publications Branch. OCLC 4377202.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mareth Line. |