Macuahuitl

A macuahuitl ([maːˈkʷawit͡ɬ]) is a weapon, a wooden club with several embedded obsidian blades. The name is derived from the Nahuatl language and means "hand-wood".[2] Its sides are embedded with prismatic blades traditionally made from obsidian. Obsidian is capable of producing an edge sharper than high quality steel razor blades. The macuahuitl was a standard close combat weapon.

| Macuahuitl | |

|---|---|

A modern recreation of a ceremonial macuahuitl | |

| Type | Macuahuitl |

| Place of origin | Mexico |

| Service history | |

| In service | Classic to Post-Classic stage (900–1570) |

| Used by | Mesoamerican civilizations, including Aztecs Indian auxiliaries of Spain[1] |

| Wars | Aztec expansionism, Mesoamerican wars Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2.0–3.0 kg (4.4–6.6 lb) |

| Length | 90–120 cm (35–47 in) |

| Blade type | Straight, thick, double-edged, tapered |

| Hilt type | Double-handed swept |

| Scabbard/sheath | Unknown |

| Head type | Trapezoidal |

| Haft type | Straight, wood covered by leather |

Use of the macuahuitl as a weapon is attested from the first millennium CE. By the time of the Spanish conquest the macuahuitl was widely distributed in Mesoamerica. The weapon was used by different civilisations including the Aztec (Mexicas), Maya, Mixtec and Toltec.

One example of this weapon survived the Conquest of Mexico; it was part of the Royal Armoury of Madrid until it was destroyed by a fire in 1884. Images of the original designs survive in diverse catalogues. The oldest replica is the macuahuitl created by the medievalist Achille Jubinal in the 19th century.

Description

The maquahuitl (Classical Nahuatl: mācuahuitl, other orthographic variants include maquahutil, macquahuitl and māccuahuitl),[3] a type of macana, was a common weapon used by the Aztec military forces and other cultures of central Mexico. It was noted during the 16th-century Spanish conquest of the region. Other military equipment recorded includes the round shield (chīmalli, [t͡ʃiˈmalːi]), the bow (tlahuītōlli, [t͡ɬaʔwiːˈtoːlːi]), and the spear-thrower (ahtlatl, [ˈaʔt͡ɬat͡ɬ]).[4] Its sides are embedded with prismatic blades traditionally made from obsidian (volcanic glass); obsidian is capable of producing an edge sharper than high-quality steel razor blades.[5]

It was capable of inflicting serious lacerations from the rows of obsidian blades embedded in its sides. These could be knapped into blades or spikes, or into a circular design that looked like scales.[6] The maquahuitl is not specifically a sword or a club, although it approximates a European broadsword.[2] Historian John Pohl defines the weapon as a "kind of a saw sword". [7]

According to conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo, the macuahuitl was 0.91 to 1.22 m long, and 75 mm wide, with a groove along either edge, into which sharp-edged pieces of flint or obsidian were inserted and firmly fixed with an adhesive.[8] Based on his research, historian John Pohl indicates that the length was just over a meter, although other models were larger, intended for use with both hands.[9]

According to the research of historian Marco Cervera Obregón, the sharp pieces of obsidian, each about 3 cm long, were attached to the flat paddle with a natural adhesive, bitumen.[10]

The rows of obsidian blades were sometimes discontinuous, leaving gaps along the side, while at other times the rows were set close together and formed a single edge.[11] It was noted by the Spanish that the macuahuitl was so cleverly constructed that the blades could be neither pulled out nor broken. The macuahuitl was made with either a one-handed or two-handed grip, as well as in rectangular, ovoid, or pointed forms. Two-handed macuahuitl have been described as being "as tall as a man".[12]

Typology

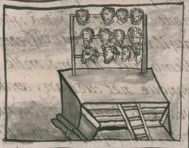

According to National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH) archaeologist Marco Cervera Obregón, there were two versions of this weapon: The macuahuitl, about 70 to 80 centimetres (28 to 31 in) long with six to eight blades on each side; and the mācuāhuitzōctli, a smaller club about 50 centimetres (20 in) long with only four obsidian blades.[13]

Specimens

According to Ross Hassig, the last authentic macuahuitl was destroyed in 1884 in a fire in the Real Armería in Madrid, where it was housed beside the last tepoztopilli.[12][14] According to Marco Cervera Obregón, there is supposed to be at least one macuahuitl in a Museo Nacional de Antropología warehouse,[15] but it is possibly lost.[16]

No actual maquahuitl specimens remain and the present knowledge of them comes from contemporaneous accounts and illustrations that date to the 16th century and earlier.[11]

Origins and distribution

The maquahuitl predates the Aztecs. Tools made from obsidian fragments were used by some of the earliest Mesoamericans. Obsidian used in ceramic vessels has been found at Aztec sites. Obsidian cutting knives, sickles, scrapers, drills, razors, and arrow points have also been found.[17] Several obsidian mines were close to the Aztec civilisations in the Valley of Mexico as well as in the mountains north of the valley.[18] Among these were the Sierra de las Navajas (Razor Mountains), named after their obsidian deposits. Use of the maquahuitl as a weapon is attested from the 1st millennia CE. A Mayan carving at Chichen Itza shows a warrior holding a macuahuitl, depicted as a club having separate blades sticking out from each side. In a mural, a warrior holds a club with many blades on one side and one sharp point on the other, also a possible variant of the macuahuitl.[11][19]

By the time of the Spanish conquest the macuahuitl was widely distributed in Mesoamerica, with records of its use by the Aztecs, Mixtecs, Tarascans, Toltecs and others.[20] It was also commonly used by the Indian auxiliaries of Spain,[21] though they favored Spanish swords. As Mesoamericans in Spanish service needed a special permission to carry European arms, metal swords brought Indian auxiliaries more prestige than maquahuitls in the eyes of Europeans as well as natives.[22]

Effectiveness

The macuahuitl was sharp enough to decapitate a man.[17] According to an account by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Hernán Cortés’s conquistadors, it could even decapitate a horse:

Pedro de Morón was a very good horseman, and as he charged with three other horsemen into the ranks of the enemy the Indians seized hold of his lance and he was not able to drag it away, and others gave him cuts with their broadswords, and wounded him badly, and then they slashed at the mare, and cut her head off at the neck so that it hung by the skin, and she fell dead.[23]

Another account by a companion of Cortés known as The Anonymous Conqueror tells a similar story of its effectiveness:

They have swords of this kind – of wood made like a two-handed sword, but with the hilt not so long; about three fingers in breadth. The edges are grooved, and in the grooves they insert stone knives, that cut like a Toledo blade. I saw one day an Indian fighting with a mounted man, and the Indian gave the horse of his antagonist such a blow in the breast that he opened it to the entrails, and it fell dead on the spot. And the same day I saw another Indian give another horse a blow in the neck, that stretched it dead at his feet.

— "Offensive and Defensive Arms", page 23[24]

Another account by Francisco de Aguilar reads:

They used ... cudgels and swords and a great many bows and arrows ... One Indian at a single stroke cut open the whole neck of Cristóbal de Olid’s horse, killing the horse. The Indian on the other side slashed at the second horseman and the blow cut through the horse’s pastern, whereupon this horse also fell dead. As soon as this sentry gave the alarm, they all ran out with their weapons to cut us off, following us with great fury, shooting arrows, spears and stones, and wounding us with their swords. Here many Spaniards fell, some dead and some wounded, and others without any injury who fainted away from fright.[25]

.jpg)

Given the importance of human sacrifice in Nahua cultures, their warfare styles, particularly those of the Aztec and Maya, placed a premium on the capture of enemy warriors for live sacrifice. Advancement into the elite cuāuhocēlōtl warrior societies of the Aztec, for example, required taking 20 live captives from the battlefield. The macuahuitl thus shows several features designed to make it a useful tool for capturing prisoners: fitting spaced instead of contiguous blades, as seen in many codex illustrations, would intentionally limit the wound depth from a single blow, and the heavy wooden construction allows weakened opponents to be easily clubbed unconscious with the flat side of the weapon. The art of disabling opponents using an un-bladed macuahuitl as a sparring club was taught from a young age in the Aztec Tēlpochcalli schools.[26]

The macuahuitl had many drawbacks in combat versus European steel swords. Despite being sharper, prismatic obsidian is also considerably more brittle than steel; obsidian blades of the type used on the macuahuitl tended to shatter on impact with other obsidian blades, steel swords or plate armour. Obsidian blades also have difficulty penetrating European mail. The thin, replaceable blades used on the macuahuitl were easily dulled or chipped by repeated impacts on bone or wood, making artful use of the weapon critical. It takes more time to lift and swing a club than it does to thrust with a sword. More space is needed as well, so warriors advanced in loose formations and fought in single combat.[27]

Experimental archaeology

Replicas of the macuahuitl have been produced and tested against sides of beef for documentary shows on the History and Discovery channels, to demonstrate the effectiveness of this weapon. On the History show Warriors, special forces operator and martial artist Terry Schappert injured himself while fencing with a macuahuitl; he cut the back of his left leg as the result of a back-swing motion.[28]

For SpikeTV's reality program Deadliest Warrior a replica was created and tested against a model of a horse's head created using a horse's skeleton and ballistics gel. Actor and martial artist Éder Saúl López was able to decapitate the model, but it took three swings. Blows from the replica macuahuitl were most effective when it was swung and then dragged backwards upon impact, creating a sawing motion. This led Max Geiger, the computer programmer of the series, to refer to the weapon as "the obsidian chainsaw". This may have been due to the crudely made obsidian cutting edges of the weapon used in the show, compared with more finely made prismatic obsidian blades, as in the Madrid specimen.[29]

References

Footnotes

- Asselbergs (2014), p. 78.

- "The Fearsome Close-Quarter Combat Weapon of the Aztecs". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- Stephanie Wood (ed.). "Macuahuitl". Nahuatl Dictionary/Diccionario del náhuatl. Wired Humanities Projects, University of Oregon. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Soustelle (1961), p. 209.

- Buck, BA (March 1982). "Ancient Technology in Contemporary Surgery". The Western Journal of Medicine. 136 (3): 265–269. PMC 1273673. PMID 7046256.

- Coe (1962), p. 168.

- Pohl, John. Aztec Warrior: AD 1325–1521. Bloomsbury.

- From A. P. Maudslay's translation commentary of Bernal Díaz del Castillo's Verdadera Historia de la Conquista de Nueva España (republished as The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico, p. 465).

- Pohl, John. Aztec Warrior: AD 1325–1521. Bloomsbury.

- These Peculiar Aztec ‘Swords’ Struck Fear Into the Hearts of the Conquistadors

- Hassig, 1988, p. 85

- Hassig, 1988 p. 83.

- Cervera Obregón 2006A, p. 128

- Hassig 1992, p. 169.

- Cervera Obregón 2006A, p. 137

- Cerevera Obregón, Marco (19 February 2009). "El macuahuitl, arqueologia experimental". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- Smith, 1996, p. 86

- Smith, 1996, p. 87

- Cervera Obregón, Marco (2006). "The macuahuitl: an innovative weapon of the Late Post-Classic in Mesoamerica" (PDF). Arms & Armour. 3 (2): 137–138. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- Obregón, 2006A, pp. 137–138

- Asselbergs (2014), pp. 76, 78.

- Asselbergs (2014), p. 79.

- Diaz del Castillo, p. 126

- The Anonymous Conqueror. (1917). Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitán The Cortés Society: Archived 6 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine Chapter 4. New York.

- Francisco de Auguilar, untitled account, in The Conquistadors, 139–140, 155.

- Berdan and Anawalt, The Essential Codex Mendoza, v. 2–4. UCal Press; 1997. Folio 62-R, p. 173.

- Townsend, 2000, p. 24

- "Warriors" Mayan Armageddon (TV Episode 2009), retrieved 29 May 2018

- Gonsalves, Kiran; Ojeda, Michael S. (11 May 2010), Aztec Jaguar vs. Zande Warrior, Cody Jones, Jay Charlot, Darell M. Davie, archived from the original on 10 February 2017, retrieved 29 May 2018

Sources

- Asselbergs, Florine G. L. (2014). "The Conquest in Images: Stories of Tlaxcalteca and Quauhquecholteca Conquistadors". In Laura E. Matthew; Michel R. Oudijk (eds.). Indian Conquistadors: Indigenous Allies in the Conquest of Mesoamerica. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 65–101. ISBN 978-0806143255.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baquedano, Elizabeth (1993). Aztec, Inca & Maya. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0789465962.

- Coe, Michael D. (1962). Mexico. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 39433014.

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1956) [ca.1568]. Genaro Garcia (ed.). The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico 1517–1521. A. P. Maudslay (Trans.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy. ISBN 978-0415344784.

- Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806121215.

- Hassig, Ross (1992). War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520077348.

- James, Peter; Nick Thorpe (1994). Ancient Inventions. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0345401021.

- Smith, Michael E. (1996). The Aztecs. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1557864963.

- Soustelle, Jacques (1961). Daily Life of the Aztecs: On the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Patrick O’Brian (Trans.). London: Phoenix Press. OCLC 503937820.

- Townsend, Richard F. (2000). The Aztecs (revised ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500281321.

- Peter Weller (Host), Jin Gaffer( Writer and Director), Mark Cannon (Series Director), Randy Martini (Series Producer) (2006). Jeremy Siefer (ed.). Engineering an Empire: The Aztecs (Documentary). History Channel.

- Wimmer, Alexis (2006). "Dictionnaire de la langue nahuatl classique" (online version). Retrieved 22 August 2007. (in French and Nahuatl languages)

- Cervera Obregón, Marco (2006a). "The macuahuitl: an innovative weapon of the Late Post-Classic in Mesoamerica" (PDF). Arms & Armour. 3 (2): 137–138. doi:10.1179/174962606x136892. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- Cervera Obregón, Marco A. (2006b). "The macuahuitl: A probable weaponry innovation of the Late Postclassic in Mesoamérica". Arms and Armour, Journal of the Royal Armouires, Leeds. 3.

- Cervera Obregón, Marco A. (2007a). "El macuahuitl, un arma del Posclásico Tardío en Mesoamérica". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). 84.

- Cervera Obregón, Marco A. (2007b). "El armamento entre los mexicas" (in Spanish). Gladius, CSIC, Polifemo, Madrid, con prólogo de Ross Hassig. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - 16.Francisco de Auguilar, untitled account, in The Conquistadors, 139–140, 155.

External links

- Glimmerdream: obsidian history

- FAMSI: John Pohl's Mesoamerica, Aztec Society/Warfare