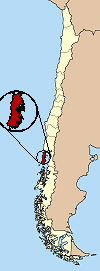

Chiloé Island

Chiloé Island (Spanish: Isla de Chiloé), (Spanish pronunciation: [tʃi.loˈe]) also known as Greater Island of Chiloé (Isla Grande de Chiloé), is the largest island of the Chiloé Archipelago off the coast of Chile, in the Pacific Ocean. The island is located in southern Chile, in the Los Lagos Region.

| Native name: Isla de Chiloé or Isla Grande de Chiloé | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 42°40′36″S 73°59′36″W |

| Archipelago | Chiloé Archipelago |

| Area | 8,394 km2 (3,241 sq mi) |

| Length | 190 km (118 mi) |

| Width | 65 km (40.4 mi) |

| Administration | |

Chile | |

| Province | Chiloé Province |

| Largest settlement | Castro (pop. 39,366) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 154,775 (2002) |

| Pop. density | 18.44/km2 (47.76/sq mi) |

Of roughly rectangular shape, the southwestern half of the island is a wilderness of contiguous forests and swamps. Mountains in the island form a belt running from the northwestern to the southeastern corner of the island. Cordillera del Piuchén make up the northern mountains and the more subdued Cordillera de Pirulil gathers the southern mountains. The landscape of the northeastern sectors of Chiloé Island is dominated by rolling hills with a mosaic of pastures, forests and cultivated fields. While the western shores are rocky and relatively straight the eastern and northern shores contain many inlets, bays and peninsulas and it is here where all towns and cities lie.

Geographically the bulk of the island is a continuation of the Chilean Coast Range, with the sea of Chiloé being a submerged portion of the Chilean Central Valley.[1] The climate is cool temperate oceanic with Mediterranean precipitation pattern.

Geography

With an area of 8,394 square kilometres (3,241 sq mi), Chiloé Island is the second largest island in Chile (after the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego), the largest island completely within Chile, and the fourth largest in South America. It is separated from the Chilean mainland by the Chacao Strait (Canal Chacao) to the north, and by the Gulf of Ancud (Golfo de Ancud) and the Gulf of Corcovado (Golfo Corcovado) to the east; the Pacific Ocean lies to the west, and the Chonos Archipelago lies to the south, across the Boca del Guafo. The island is 190 km (118 mi) from north to south, and averages 55–65 km (34–40 mi) wide. The capital is Castro, on the east side of the island; the second largest town is Ancud, at the island's northwest corner, and there are several smaller port towns on the east side of the island, such as Quellón, Dalcahue and Chonchi.

Chiloé Island and the Chonos Archipelago are a southern extension of the Chilean coastal range at Chilean Patagonia, which runs north and south, parallel to the Pacific coast and the Andes Mountains. The Chilean Central Valley lies between the coastal mountains and the Andes, of which the Gulfs of Ancud and Corcovado form the southern extension. Mountains run north and south along the spine of the island. The east coast is deeply indented, with several natural harbors and numerous smaller islands.

Climate

Chiloé runs from 41º47′S to 43º26′S, and has a humid, cool temperate climate. The western side of the island is rainy and wild, home to the Valdivian temperate rain forests, one of the world's few temperate rain forests. Chiloé National Park (Parque Nacional de Chiloé) is located on the island's western shore and Tantauco Park (Parque Tantauco) a private natural reserve created and owned by Chilean business magnate and President of Chile Sebastián Piñera, is located on the island's southern shore and both include parts of the coastal range. The eastern shore, in the rain shadow of the interior mountains, is warmer and drier.

Alfaguara project

The northwestern of Chiloé Island in Chiloé National Park has a great diversity of marine fauna, including blue whale, sei whale, Chilean dolphins and Peale's dolphins; sea lions, marine otters, and Magellanic penguin and Humboldt penguins. Nevertheless, this relatively undisturbed area faces different threats, like urban development, habitat degradation, land and marine pollution.

The Alfaguara project (blue whale project), conducted by the Cetacean Conservation Center, is based at Puñihuil on the northwest coast. The project combines long-term research, educational and capacity building programs for marine conservation combined with the sustainable development of the local communities.[2] The Islotes de Puñihuil Natural Monument is a group of three islets to the west and north of Puñihuil. The monument is the only known shared breeding site for Humboldt and Magellanic penguins. It is also a breeding area for other species, such as the red-legged cormorant and kelp gull.[3]

History

Chiloé has been described by Renato Cárdenas, historian at the Chilean National Library, as “a distinct enclave, linked more to the sea than the continent, a fragile society with a strong sense of solidarity and a deep territorial attachment.”[4]

Chiloé's history began with the arrival of its first human inhabitants more than 7,000 years ago.[5] Spread along the coast of Chiloé are a number of middens - ancient dumps for domestic waste, containing mollusc shells, stone tools and bonfire remains. All of these remains indicate the presence of nomadic groups dedicated to the collection of marine creatures (clams, mussels and choromytilus chorus, among others) and to hunting and fishing.[6]

When the Spanish conquistadores arrived on Chiloé Island in the 16th Century, the island was inhabited by the Chono, Huilliche and Cunco peoples. The original peoples navigated the treacherous waters of the Chiloé Archipelago in boats called dalcas with skill that impressed the Spaniards.[7]

The first Spaniard to sight the coast of Chiloé was the explorer Alonso de Camargo in 1540, as he was travelling to Peru.[8] However, in an expedition ordered by Pedro de Valdivia, captain Francisco de Ulloa reached the Chacao Channel in 1553 and explored the islands forming the archipelago, and is thus considered the first discoverer of Chiloé.[7] In 1558, Spanish soldier García Hurtado de Mendoza began an expedition which would culminate in the Chiloé archipelago being claimed for the Spanish crown.

The city of Castro was founded in 1567.[9] The island was originally called New Galicia by the Spanish discoverers,[10] but this name did not stick and the name Chiloé, meaning “place of seagulls” in the Huilliche language, was given to the island.[4]

Jesuit missionaries to Chiloé Island, charged with the evangelization of the local population arrived on Chiloé at the turn of the 17th Century and built a number of chapels throughout the archipelago. By 1767 there were already 79 and today more than 150 wooden churches built in traditional style can be found on the islands, many of these declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.[8][11] Following the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, the Franciscans assumed responsibility for the religious mission to Chiloé from 1771.[9]

Chiloé only became part of the Chilean republic in 1826, eight years after independence and following the two failed campaigns for independence in 1820 and 1824.[12] From 1843, a large number of Chilotes (as inhabitants of the island are called) migrated to Patagonia in search of work, mainly in Punta Arenas, but as living and working conditions in Chiloé improved in the following century this migration began gradually to decrease.[13]

In the 19th century, Chiloé was a center for foreign whalers, particularly French whalers. From the middle of the 19th century and until the beginning of the 20th century, Chiloé was the main producer of railroad ties for the whole continent.[14] From this point on, new towns dedicated to this industry were formed, including Quellón, Dalcahue, Chonchi and Quemchi were established. From 1895, lands were given to European settlers and also to large manufacturing industries.

With the rise of farming, inland areas of Chiloé Island began to be occupied; previously only the coastline had been inhabited. With the construction of the railroad between Ancud and Castro in 1912, the occupation of inland zones was completed. This railroad is no longer in service.[15]

Access

In late 2012, LAN Airlines became the first airline to offer flights to Chiloé Island, inaugurating a regular service between Puerto Montt and the airport of Mocopulli, Dalcahue.[16] Previously the only means of access to Chiloé island was via a ferry service across the Chacao Channel.

A project to build a bridge from Chiloé Island to the mainland of Chile was initially proposed in 1972 and was eventually launched under the government of Ricardo Lagos (2000-2006) who launched the project as part of works to celebrate the Bicentennial of Chile. In 2006, however, the Chacao Channel bridge project was cancelled by the Ministry of Public Works after concerns about its total cost, which was estimated to be higher than the initial budget for the project. In May 2012, President Sebastián Piñera again revived the project, announcing an international bidding process would be opened to present the best solution for the construction of the bridge, with a US$740 million investment limit.[17][18]

See also

- Chiloé Archipelago

- Churches of Chiloé

- 1712 Huilliche rebellion

- Chacao Channel bridge

- Ecotourism in the Valdivian Temperate Rainforest

References

- Börger Olivares, Reinaldo (1983). Geografía de Chile (in Spanish). Tomo II: Geomorfología. Instituto Geográfico Militar.

- "Alfaguara project" (PDF). Rufford Small Grants Foundation. January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Simeone, Alejandro; Roberto P. Schlatter (1998). "Threats to a Mixed-Species Colony of Spheniscus Penguins in Southern Chile". Colonial Waterbirds. 21 (3): 418–421. doi:10.2307/1521654. JSTOR 1521654.

- Larry Rohter. For some on island, a planned project is a bridge too near. NY Times. August 3, 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Carlos Ocampo E. y Pilar Rivas H. Poblamiento temprano de los extremos geográficos de los canales patagónicos: Chiloé e Isla Navarino 1.Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena 36 (vol. especial): pp. 317-331. doi:10.4067/S0717-73562004000300034, ISSN 0717-7356

- Ricardo Álvarez. Conchales arqueológicos y comunidades locales de Chiloéa través de una experiencia de educación patrimonial. Chungará, Revista de Antropología Chilena Vol.36 (vol. especial) pp.1151-1157. Sept 2004. doi:10.4067/S0717-73562004000400049, ISSN 0717-7356.

- Breve Historia de Chiloé. Mav.cl (Museo de Arte Visual: Visual Arts Museum). Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Ramón Gutiérrez. Las misiones circulares de los jesuitas en Chiloé. Apuntes para una historia singular de la evangelización. Apuntes Vol.20, No.1: 50-61.

- Rodrigo A. Moreno J. Chiloé Archipelago and the Jesuits: The geographic environment of the mission in the XVII and XVIII centuries. ISSN 0718-2244. in Spanish. MAGALLANIA (Chile), 2011. Vol. 39(2):47-55.

- Isla Chiloé: History. Trip Advisor. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- World Heritage Committee Inscribes 61 New Sites on World Heritage List. whc.unesco.org. November 30, 2000. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Diego Barros Arana. Las campañas de Chiloé (1820-1826). 1856. Documento Justificativo Nº 14. Memoria histórica presentada a la Universidad de Chile en la sesión solemne de 7 de diciembre de 1856. Santiago de Chile

- El influjo de los chilotes en la Patagonia. Santiago de Chile: Anaquel Austral (7 de octubre de 2010). Retrieved 14 January 2013..

- Roberto Maldonado C. Estudios geográficos é hidrográficos sobre Chiloé. Departamento de Navegación e Hidrografía, Chile. 1897. Establecimiento Poligráfico "Roma". Santiago de Chile. P.379

- Danilo Vega. Tras el tren Chilote: Los Cazadores del Camahueto. El Repuertero. 27 October 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2013

- Aerolínea Lan realiza primer vuelo hacia la isla de Chiloé. La Tercera. 6 November 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Anuncio de bono de alimentación y puente en Chiloé destacan en cuenta pública de Piñera". Emol.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- "Licitación por puente Chacao será por US$ 740 millones" (PDF) (in Spanish). La Tercera. 2012-05-22. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-16. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

External links

![]()