Lüshunkou District

Lüshunkou District (also Lyushunkou District; simplified Chinese: 旅顺口区; traditional Chinese: 旅順口區; pinyin: Lǚshùnkǒu Qū) is a district of Dalian, in Liaoning province, China. Also formerly called Lüshun City (旅顺市; 旅順市; Lǚshùn Shì) or literally Lüshun Port (旅顺港; 旅順港; Lǚshùn Gǎng), it was formerly known as both Port Arthur (亚瑟港; 亞瑟港; Yàsè Gǎng; Russian: Порт-Артур, romanized: Port-Artur) and Ryojun (Japanese: 旅順). The district's area is 512.15 square kilometres (197.74 sq mi) and its permanent population as of 2010 is 324,773.[2][3]

Lüshunkou 旅顺口区 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

View of Lüshun's harbor and town from an old Japanese fortification | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

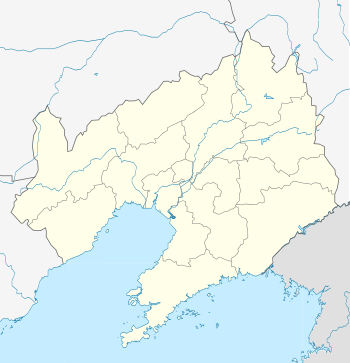

Lüshunkou Location in Liaoning | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates: 38°51′12″N 121°15′01″E[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Province | Liaoning | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sub-provincial city | Dalian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 512.15 km2 (197.74 sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population (2010)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 324,773 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Density | 630/km2 (1,600/sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

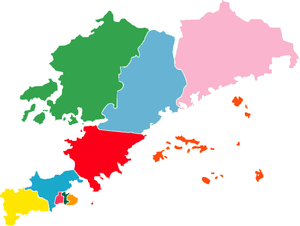

| Dalian district map |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Division code | 210212 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lüshunkou is located at the extreme southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula. It has an excellent natural harbor, the possession and control of which became a casus belli of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). Japanese and then Russian administration was established in 1895 and continued until 1905 when control was ceded to Japan. During that period, it was world-famous and was more significant than the other port on the peninsula, Dalian proper. In English-language diplomatic, news, and historical writings, it was known as Port Arthur, and during the period when the Japanese controlled and administered the Liaodong (formerly Liaotung) Peninsula it was called Ryojun (旅順), the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters in the city's name. After the Japanese defeat in World War II, the city was under the administration of the Soviet Union, which rented the port from China, until 1950. Although the Soviets presented the port to China in 1950, Soviet troops remained in the city until 1955.

Geography

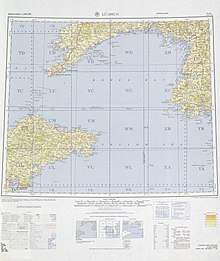

Central Dalian is some 64 kilometres (40 miles) farther up the coast, sprawling around the narrowest neck of the Liaodong Peninsula (simplified Chinese: 辽东半岛; traditional Chinese: 遼東半島; pinyin: Liáodōng Bàndǎo), whereas Lüshun occupies its southern tip. (See Landsat Map below Zoomed – Lüshun City surrounds the lake-like structure clearly visible near the peninsular tip—the lake-like feature is the inner natural harbour of the port, a very well-sheltered and fortifiable harbour to 19th century eyes.)

Clearly seen on the map (above right) are the Liaodong Peninsula and its relation to Korea, the Yellow Sea (Chinese: 黄海) to its southeast, the Korea Bay (Chinese: 西朝鲜湾) to its due east, and the Bohai Sea (or Gulf) (Chinese: 渤海) to its west. Beijing is almost directly (due west-northwest) across the Bo Hai Gulf from the port city.

Earlier history

Surrounded by ocean on three sides, this strategic seaport was originally known to the Chinese as Lüshun. It took its English name, Port Arthur, from a British Royal Navy Lieutenant named William C. Arthur who surveyed the harbor in the gunboat HMS Algerine in August 1860, during the Second Opium War. At that time Lüshun was an unfortified fishing village.

Late-19th century colonial era

In the late 1880s, the German company Krupp was contracted by the Chinese government to build a series of fortifications around Port Arthur. Reportedly, this was after local contractors had "made an extensive bungle of the job".[4]

Port Arthur first came into international prominence during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). Following Japan's defeat of Chinese troops at Pyongyang in Korea in September 1894, the Japanese First and Second Armies converged on the Liaodong Peninsula by land and sea. Japanese war planners, ambitious for control of the Liaodong Peninsula and Port Arthur and also cognizant of that port's strategic position controlling the northern Yellow Sea routes and the passage to Tianjin, were determined to seize it.

Following only token resistance during the day and night of 20–21 November 1894, Japanese troops entered the city on the morning of 21 November. Several Western newspaper correspondents present at the time related the widespread massacre of Chinese inhabitants of the city by the victorious Japanese troops, apparently in response to the murderous treatment the Chinese had shown Japanese prisoners of war at Pyongyang and elsewhere. Foremost among the correspondents was James Creelman of the New York World. Though at least one American correspondent present completely contradicted Creelman's account, there is "little doubt" that the Japanese troops "indiscriminately killed" thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians,[5] and the story of a Japanese massacre soon spread among the Western public, damaging Japan's public image and the movement in the United States to renegotiate the unequal treaties between that country and Japan. The event came to be known as the Port Arthur massacre.

An account of a US sailor who visited the port in the weeks prior to the attack commented that the Chinese soldiers were "ridiculous". They lacked any semblance of military bearing, their dress was unkempt and untidy, and they wandered about the place with little in the way of direction or smartness associated with professional soldiers. He stated that at the time, the garrison numbered approximately 20,000 soldiers, but from his estimation, it should have had between 30,000 and 40,000 men stationed there. He opined that the Japanese could have taken the port with one third of its force, but that against disciplined soldiers, the place should have been impenetrable.[6]

Japan went on to occupy Port Arthur and to seize control of the whole Liaodong Peninsula as spoils of war. As part of the terms of the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki concluding the war, Japan was granted the Liaodong Peninsula but had to cede the territory when threatened jointly with war by France, Germany and Russia in what is called the Triple Intervention of 1895. This was seen as a great humiliation in Japan.

Two years later, Russia coerced a lease of the Liaodong Peninsula from China and gained railroad right-of-way to join the Liaodong Peninsula to the Chinese Eastern Railway with a line running from Port Arthur and nearby Dalny (Dalian) to the Chinese city of Harbin (see Kwantung Leased Territory), and systematically began to fortify the town and harbor at Port Arthur. This railway from Port Arthur to Harbin became a southern branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway (not to be confused with the South Manchurian Railway, the name of a company that undertook its management during the later Japanese period after 1905). Tsar Nicholas II believed this acquisition of a Pacific port would enhance Russian security, and extend its economic influence. He was also falsely informed that the British were considering seizing the port.[7] All this was an additional goad to an already seething Japan. It was a hard lesson in international geopolitics Japan would not soon forget.

The Russian town of Dalny (Dalien/Dalian) was undeveloped in this era prior to 1898 when the Russian Tsar Nicholas II founded the town of Dalny (sometimes Dalney). In 1902, the Russian viceroy de-emphasized Dalny (building a palace and cultural edifices instead at Port Arthur), except as a commercial port while continuing the development of manufacturing.

Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)

Ten years later, Port Arthur again played a central role in war in China. After the Boxer Rebellion (1900–01) had been extinguished by an international coalition of troops, Russia refused to withdraw its reinforcements from Manchuria and instead began to fortify and garrison the entire route along the Southern Manchurian Railway. With this development, Japan proposed the two powers meet and discuss their respective roles in eastern Manchuria, as the area was considered being in their respective spheres of influence. Talks were conducted between 1902 and 1904. While numerous proposals and agreement papers were generated between the two powers, Russia continued the de facto annexation of territory through fortification and garrison, if not de jure; while employing stalling tactics in its negotiations. In the end, with over two years of intensive bilateral negotiations having gotten nowhere in clarifying each country's rights, prerogatives, and interests in inner Manchuria, Japan declared war on Russia in February 1904.

The Battle of Port Arthur

.jpg)

The Battle of Port Arthur, the opening battle of the Russo-Japanese War, was fought in the heavily fortified harbor of the town of Port Arthur/Lüshun on 9 February 1904 when the Japanese attacked at night with torpedoes, followed by a brief daylight skirmish by major surface combatants.

By the end of July 1904, the Japanese army had pushed down the Liaodong peninsula and was at the outer defenses of Port Arthur. The fact that Japanese forces had closed to within artillery range of the harbor in early August 1904 led directly to the naval Battle of the Yellow Sea which solidified Japan's command of the sea, where her fleets continued to blockade the harbor. Virtually all the battles of the war until July 1904 were strategic battles for territorial gain or position leading to the investment and siege of the port city.

The port eventually fell 2 January 1905 after a long train of battles on land and sea during which the Japanese occupied the whole of the Korean Peninsula, split the Russian Army, devastated the Russian Fleet, and cut off the source of supplies on the railway from Harbin, culminating in the bloody battle known as the Siege of Port Arthur (June–January; some sources place the siege start in late July, a technical difference due to definitions).

After World War II

The Japanese-controlled Ryojun City had 40 districts. The Chinese Lüshun City was established on 25 November 1945 to replace Ryojun. The city was a subdivision of a larger Lüda City and contained 40 villages in 3 districts: Dazhong (大众区; 大眾區), Wenhua (文化), and Guangming (光明). In January 1946, Wenhua was merged into Dazhong, and the 40 villages were reduced to 23 communes (坊). In January 1948, the remaining two districts were merged into one: Shinei (市内区; 市內區), with 12 communes.

On 7 January 1960, Lüshun City was renamed Lüshunkou District, still under Lüda. In 1981, Lüda was renamed Dalian, with Lüshunkou remaining a constituent district. In 1985, 7 of Lüshunkou's 9 townships were upgraded to towns.

Administrative divisions

Lüshunkou District administers 9 subdistricts; all of the former towns were either abolished, merged or converted into subdistricts themselves.[8]

- Dengfeng Subdistrict (登峰街道)

- Desheng Subdistrict (得胜街道)

- Shuishiying Subdistrict (水师营街道)

- Longwangtang Subdistrict (龙王塘街道)

- Tieshan Subdistrict (铁山街道)

- Shuangdaowan Subdistrict (双岛湾街道)

- Sanjianpu Subdistrict (三涧堡街道)

- Changcheng Subdistrict (长城街道)

- Longtou Subdistrict (龙头街道)

Today

The district's southern half along Lüshun South Road, central Lüshun and the Naval Port zone continue to be off-limits to foreigners, although Lüshunkou District is thoroughly modernized. World Peace Park opened on the western coast of Lüshun, on the Bohai Sea, and is a new sightseeing spot. North of the Park were established the Lüshun Development Zone, and Lüshun New Port (on Yangtou Bay) where the railroad ferry across the Yellow Sea to Yantai is being planned.

The universities in downtown Dalian are being relocated to Lüshunkou. Dalian Jiaotong University (formerly Dalian Railroad University) moved its Software School to the area near the new port, and Dalian University of Foreign Languages and Dalian Medical University relocated their main campuses to the eastern slope of Baiying Mountain, on Lüshun South Road. Dalian Fisheries University is in the process of moving its English and Japanese language schools to Daheishi, on Lüshun North Road. From late 2006, Sinorail has operated Bohai Train Ferry between Lüshun, Dalian, and Yantai, Shandong.

Old and new names of main facilities

The historic and modern names, translated into English, of landmark facilities in Lüshun are as follows:

| Under Russian rule | Under Japanese rule | Under Chinese rule |

|---|---|---|

| The Old Town | ||

| Unknown | Lüshun City Hall | Commercial Bldg. on right of New Mart Supermarket |

| Unknown | Public Welfare Office | Naval Hotel |

| -- | Lüshun Branch, Korean Bank | Lüshun Branch, Commercial Bank of China |

| -- | Lüshun No. 1 Primary School | A Naval Facility (on left of Zhangjian Rd. South 3rd Alley) |

| Red Cross Hospital | Lüshun Hospital & Medical School | A Naval Facility (Lüshunkou Hospital on north side) |

| -- | Kwantung High Court | Old Kwantung High Court (inside Hospital premises) |

| Lüshun Jail (Gray Walled Bldgs.) | Lüshun Jail (Extended with Red Walled Bldgs.) | Russo-Japanese Jail (Anti-Imperialist Propaganda Facility) |

| -- | Lüshun Danish Lutheran Church | Lüshunkou Christian Church |

| -- | Hyochu (Showing Loyalty) Tower | White Jade Tower |

| -- | Asahi (Morning Sun) Plaza | Friendship Park |

| The New Town | ||

| Unknown | Japan Bridge (over the Long He) | Liberation Bridge |

| Russian Marines Hqs. | Lüshun Institute of Technology | Navy Hospital No. 406 |

| Unknown | Lüshun High School | A Naval Facility (Lüshun command) |

| A German Merchant's Store | Lüshun (No. 1) Middle School | A Naval facility (No. 58 Stalin Rd.) |

| Meeting Place of Sniper Unit's Non-commissioned Officers | Lüshun No. 2 Primary School | Dalian City No. 56 Middle School |

| Ji Fengtai's Shop | The Lüshun Yamato Hotel | Shop & Hostel |

| Unknown | Lüshun No. 2 Middle School | Not Used |

| Photoshop/Town Hall/Restaurant | Lüshun Girls' High School | Navy Related Families' Living Quarters |

| Unknown | Kodama Ground | Ground for Navy |

| Unknown | Korakuen Park | Lüshun Museum Park |

Source: "Lüshun under Russian Rule" (in Japanese; Lüshun Library, 1936), as quoted in "Lüshun under Russian Rule" (Abridged) in "Journal Commemorating the 95th Anniversary of Lüshun Institute of Technology" (in Japanese; Tokyo, 2006).

References

Citations

- Google (2 July 2014). "Shuishiying Sub-district" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- Dalian Statistical Yearbook 2012 (《大连统计年鉴2012》). Accessed 8 July 2014.

- 2010 Census county-by-county statistics (《中国2010年人口普查分县资料》). Accessed 8 July 2014.

- James Allen (1898). Under the dragon flag: My experiences in the Chino-Japanese war. Frederick A. Stokes Company. p. 39. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- Chushichi Tzusuki, The Pursuit of Power in Modern Japan 1825–1995, OUP, 2003 (reprint of 2000 ed), p. 128

- James Allen (1898). Under the dragon flag: My experiences in the Chino-Japanese war. Frederick A. Stokes Company. pp. 41–42. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- Sebag Montefiore, Simon (2016). The Romanovs. United Kingdom: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 503–504.

- 2018年统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码:旅顺口区 (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Sources

- F.R. Sedwick, (R.F.A.), The Russo-Japanese War, 1909, The Macmillan Company, N.Y.

- Colliers (Ed.), The Russo-Japanese War, 1904, P.F. Collier & Son, New York

- Dennis and Peggy Warner, The Tide at Sunrise, 1974, Charterhouse, New York

- William Henry Chamberlain, Japan Over Asia, 1937, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston

- Tom McKnight, PhD, et al.; Geographica (ATLAS), Barnes and Noble Books and Random House, New York, 1999–2004, 3rd revision, ISBN 0-7607-5974-X