Lithuanization

Lithuanization (or Lithuanianization) is a process of cultural assimilation, where Lithuanian culture or its language is voluntarily or forcibly adopted.

History

The Lithuanian annexation of Ruthenian lands between the 13th and 15th centuries was accompanied by some Lithuanization. A large part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania remained Ruthenian; due to religious, linguistic and cultural dissimilarity, there was less assimilation between the ruling nobility of the pagan Lithuanians and the conquered Orthodox East Slavs. After the military and diplomatic expansion of the duchy into Ruthenian (Kievan Rus') lands, local leaders retained autonomy which limited the amalgamation of cultures.[1] When some localities received appointed Gediminids (rulers), the Lithuanian nobility in Ruthenia largely embraced Slavic customs and Orthodox Christianity and became indistinguishable from Ruthenian nobility. The cultures merged; many upper-class Ruthenians merged with the Lithuanian nobility and began to call themselves Lithuanians (Litvins) gente Rutenus natione Lituanus,[2][3] but still spoke Ruthenian.[4][5][6] The Lithuanian nobility became largely Ruthenian,[7] and the nobility of ethnic Lithuania and Samogitia continued to use their native Lithuanian language. It adapted Old Church Slavonic and (later) the Ruthenian language, and acquired main-chancery-language status in local matters and relations with other Orthodox principalities as a lingua franca; Latin was used in relations with Western Europe.[8] It was gradually reversed by the Polonization of Lithuania beginning in the 15th century[7] and the 19th- and early-20th-century Russification of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[9]

A notable example of Lithuanization was the 19th-century replacement of Jews (many Lithuanian Jews, but also Polish Jews), until then the largest ethnic group in Lithuania's major towns with ethnic Lithuanians migrating from the countryside. Lithuanization was primarily demographic, rather than institutionalized.[10] When Lithuania became an independent state after World War I, its government institutionalized Lithuanization.[11][12]

Interbellum Republic of Lithuania

Around the time of Lithuanian independence, the country began moving toward the cultural and linguistic assimilation of large groups of non-Lithuanian citizens (primarily Poles and Germans).[13] The Lithuanian government was initially democratic, and protected the cultural traditions of other ethnic groups; a 1917 Vilnius Conference resolution promised national minorities cultural freedom.[14] After World War I, the Council of Lithuania (the government's legislative branch) was expanded to include Jewish and Belarusian representatives.[15] The first Lithuanian governments included ministries for Jewish and Belarusian affairs;[16] when the Vilnius Region was detached from the country after Żeligowski's Mutiny, however, the largest communities of Belarusians, Jews, and Poles ended up outside Lithuania and the special ministries were abolished.[17] In 1920, Lithuania's Jewish community was granted national and cultural autonomy with the right to legislate binding ordinances; however, partly due to internal strife between Hebrew and Yiddish groups their autonomy was terminated in 1924.[18] The Jews were increasingly marginalized and alienated by the "Lithuania for Lithuanians" policy.[19]

As Lithuania established its independence and its nationalistic attitudes strengthened, the state sought to increase the use of Lithuanian in public life.[20] Among the government's measures was a forced Lithuanization of non-Lithuanian names.[21] The largest minority-school network was operated by the Jewish community; there were 49 Jewish grammar schools in 1919, 107 in 1923, and 144 in 1928.[17] In 1931, partially due to consolidation, the number of schools decreased to 115 and remained stable until 1940.[17]

Education

At the beginning of 1920, Lithuania had 20 Polish language schools for Poles in Lithuania. The number increased to 30 in 1923, but fell to 24 in 1926.[17] The main reason for the decrease was the policy of Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, which transferred students whose parents had "Lithuania" as their nationality on their passports to Lithuanian schools.[17] After the party lost control, the number of schools increased to 91. Soon after the 1926 coup d'état, nationalists led by Antanas Smetona came to power. The nationalists decided to ban attendance at Polish schools by Lithuanians; children from mixed families were forced to attend Lithuanian schools. Many Poles in Lithuania were identified as Lithuanians on their passports, and were forced to attend Lithuanian schools. The number of Polish schools decreased to nine in 1940.[17] In 1936, a law was passed which allowed a student to attend Polish school only if both parents were Poles.[20] This resulted in unaccredited schools, which numbered over 40 in 1935 and were largely sponsored by Pochodnia.[17][20] A similar situation developed concerning German schools in the Klaipėda Region.[22][23]

Lithuanian attitudes towards ethnic Poles were influenced by the concept of treating them as native Lithuanians who were Polonized over several centuries and needed to return to their "true identity".[24][25][26][27] Another major factor was the tense relationship between Lithuania and Poland about the Vilnius Region and cultural (or educational) restrictions on Lithuanians there; in 1927, the Lithuanian Education Society Rytas chairman and 15 teachers were arrested and 47 schools closed.[28]

Religion

Although the Lithuanian constitution guaranteed equal rights to all religions, the government confiscated Orthodox churches (some of which had been converted from Catholic churches). Former Eastern Catholic Churches were confiscated as well, including the Kruonis Orthodox church. Thirteen Orthodox churches were demolished.[29]

Another target group for discrimination was the Poles; anti-Polish sentiment had appeared primarily due to the occupation of Lithuania's capital Vilnius in 1920. Lithuanian Catholic priests (derogatorily called Litwomans in Polish language) promoted the Lithuanian language in equal terms to Polish, which in many places had been used forced onto the locals by central Church authorities. It was often the case, that the parish was inhabited by Lithuanian-speaking people, yet they knew their prayers only in Polish, as the priests tried Polonizing them.[30]

Eugeniusz Römer (1871-1943) noted that the Lithuanian National Revival was positive in some respects, he described some excesses, which he found often to be funny, although aggressive towards Poles and Polish culture.[31] An example of such excess was when Lithuanian priests were forced to drive out of confessional boxes people who wanted to confess in the Polish language or refused to sing Polish songs that were sung in those churches for centuries during additional services, preferring the use of Lithuanian language instead[32].

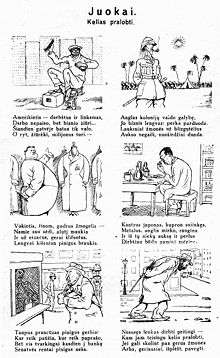

Anti-Polish propaganda was sponsored by the government; during the interwar period, caricatures and propaganda were published attacking Poles and depicting them as criminals or vagabonds.

Modern Lithuania

In modern Lithuania, which has been independent since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Lithuanization is not an official state policy. It is advocated by groups such as Vilnija, however, whose activities create tension in Polish-Lithuanian relations.[24][33][34][35] According to the former minister of education and science of Lithuania, Zigmas Zinkevičius, Lithuanian Poles are Polonized Lithuanians who "are incapable of understanding where they truly belong" and it is "every dedicated Lithuanian's duty" to re-Lithuanize them.[36] Lithuanization promoted the cooperation of Polish and Russian minorities, who support the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania.

The Law on Ethnic Minorities, which remained in force until 2010, enabled bilingual sings in areas that have "substantial numbers of a minority with a different language". After the termination of its validity, municipal authorities in Šalčininkai and Vilnius were ordered to remove bilingual Polish-Lithuanian signs, most of which had been placed during the period when such signs were permitted. In 2013, Vilnius regional court fined the administrative director of Šalčininkai District Municipality (where Poles constituted 77.8% of the population in 2011[37]) €30 for each day of delay, and in January 2014 ordered him to pay a fine of over €12,500.[38] Liucyna Kotlovska from Vilnius District Municipality was fined about €1,738.[39] Bilingual signs, even those privately purchased and placed on private property, are now seen by Lithuanian authorities as illegal. The only exception is provided for names of organisations of national minority communities and their information signs. According to the EU's Advisory Committee, this violates Lithuania's obligations under Article 11 (3) of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[40][41][42]

A Polish-Lithuanian woman protested when her last name (Wardyn) was Lithuanized to Vardyn.[43] In 2014 Šalčininkai District Municipality administrative director Boleslav Daškevič was fined about €12,500 for failing to execute a court ruling to remove Polish traffic signs. Polish and Russian schools went on strike in September 2015,[44] organised by the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania.[45]

Notes and references

- Orest Subtelny Ukraine. A History. Second edition, 1994. p. 70

- Bumblauskas, Alfredas (2005-06-08). "Globalizacija yra unifikacija". alfa.lt (in Lithuanian).

- Marshall Cavendish, "The Peoples of Europe", Benchmark Books, 2002

- Jerzy Lukowski; Hubert Zawadzki (2001). A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–45. ISBN 0-521-55917-0.

- Serhii Plokhy (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–111. ISBN 0-521-86403-8.

- "The son of Gediminas, the Grand Prince Olgerd [(Algirdas)] expanded the Ruthenian lands he inherited from his father: he attached the Polish lands to his state expelling the Tatars out. The Ruthenian lands under his sovereignty were divided between princes. However, Olgerd, the person of a strong character, controlled them. In Kiev, he installed his son, Vladimir, who started the new line of Kiev princes that reigned there for over a century and called commonly the Olelkoviches, from Olelko, Aleksandr Vladimirovich, the grand-son of Olgerd. Olgerd himself, married twice the Ruthenian princesses, allowed his sons to baptize into Ruthenian religion and, as the Ruthenian Chronicles speak, had himself baptized and died as a monk. As such, the princes that replaced the St. Vladimir's [Rurikid] line in Ruthenia, became as Ruthenian by religion and by the ethnicity they adopted, as the princes of the line that preceded them. The Lithuanian state was called Lithuania, but of course it was purely Ruthenian and would have remained Ruthenian if only the successor of Olgerd in the Great Princehood, the Jagiello wouldn't have married in 1386 to the Polish queen Jadwiga"

(in Russian) Nikolay Kostomarov, Russian History in Biographies of its main figures, section Knyaz Kostantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky (Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski) - "Within the [Lithuanian] Grand Duchy, the Ruthenian lands initially retained considerable autonomy. The pagan Lithuanians themselves were increasingly converting to Orthodoxy and assimilating into Ruthenian culture. The grand duchy's administrative practices and legal system drew heavily on Slavic customs, and Ruthenian became the official state language. Direct Polish rule in Ukraine since the 1340s and for two centuries thereafter was limited to Galicia. There, changes in such areas as administration, law, and land tenure proceeded more rapidly than in Ukrainian territories under Lithuania. However, Lithuania itself was soon drawn into the orbit of Poland."

from Ukraine. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. - (in Lithuanian) Zigmas Zinkevičius The Problem of a Slavonic Language as a Chancery Language in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Kevin O'Connor, The History of the Baltic States, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32355-0, Google Print, p.58

- Conference on Jewish Relations (corporate author) (1939). "Jewish social studies". Jewish Social Studies. Indiana University Press. VIII: 272–274.

- Ezra Mendelsohn (1983). The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 225–230. ISBN 0-253-20418-6.

- István Deák (2001). "Holocaust in Other Lands - A Ghetto in Lithuania". Essays on Hitler's Europe. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 119–122. ISBN 0-8032-1716-1.

- various authors (1994). James Stuart Olson (ed.). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 258. ISBN 0-313-27497-5.

- Laučka, Juozas (1984). "Lithuania's Struggle for Survival 1795-1917". Lituanus. 30 (4). Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- Skirius, Juozas (2002). "Vokietija ir Lietuvos nepriklausomybė". Gimtoji istorija. Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Elektroninės leidybos namai. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4. Archived from the original on 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- Banavičius, Algirdas (1991). 111 Lietuvos valstybės 1918-1940 politikos veikėjų (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Knyga. pp. 11–20. ISBN 5-89942-585-7.

- Šetkus, Benediktas (2002). "Tautinės mažumos Lietuvoje". Gimtoji istorija. Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Elektroninės leidybos namai. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4. Archived from the original on 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Judith B. Sedaitis (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. WestviewPress. pp. 39. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.

- Eli Lederhendler, Jews, Catholics, and the burden of history, Oxford University Press US, 2006, ISBN 0-19-530491-8, Google Print, p.322

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (September 1999). Ed. Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918-1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 133–137. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- Valdis O. Lumans (1993). "Lithuania and the Memelland". Himmler's Auxiliaries: The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 90–93. ISBN 0-8078-2066-0.

- SILVA POCYTĖ, DIDLIETUVIAI: AN EXAMPLE OF COMMITTEE OF LITHUANIAN ORGANIZATIONS ACTIVITIES (1934–1939) Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Edgar Packard Dean, Again the Memel Question, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Jul., 1935), pp. 695-697

- Dovile Budryte (2005). Taming Nationalism?: Political Community Building in the Post-Soviet Baltic States. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-7546-3757-3.

- Jerzy Żenkiewicz (2001). Ziemiaństwo polskie w Republice Litewskiej w okresie międzywojennym (Polish Landowners in the Republic of Lithuania Between the Wars) (in Polish). Toruń. ISBN 9788391136607.

- Zenon Krajewski (1998). Polacy w Republice Litewskiej 1918-1940 (Poles in the Lithuanian Republic) (in Polish). Lublin: Ośrodek Studiów Polonijnych i Społecznych PZKS. p. 100. ISBN 83-906321-3-6.

- Krzysztof Buchowski (1999). Polacy w niepodległym państwie litewskim 1918-1940 (Poles in the Independent Lithuanian State) (in Polish). Białystok: History Institute of the University of Białystok. p. 320. ISBN 83-87881-06-6.

- Kulikauskienė, Lina (2002). "Švietimo, mokslo draugijos ir komisijos". Gimtoji istorija. Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Elektroninės leidybos namai. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4. Archived from the original on 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- Regina Laukaitytė (2001). "Lietuvos stačiatikių bažnyčia 1918-1940 m.: kova dėl cerkvių (Orthodoxy in Lithuania between 1918 and 1940: The struggle for Orthodox churches)" (PDF). Lituanistica (in Lithuanian). 2: 15–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-03-20. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- Martinkėnas, Vincas (1990). Vilniaus ir jo apylinkių čiabuviai. Vilnius. p. 25.

Žlugus 1863 metų sukilimui, 1864–1865 m. Vilniaus generalgubernatorius M. Muravjovas sumanė drausti, o jo įpėdinis K. Kaufmanas uždraudė spausdinti lotyniškomis raidėmis lietuviškus raštus. Nuo to laiko lieuviams buvo draudžiama leisti net maldaknyges lotynišku šriftu. Ilgus metus, neturėdami lietuviškų maldaknygių, palikti lenkiškos dvasininkijos globai, nepasiduodami pravoslavijai, noromis nenoromis lietuviai rinkosi nepersekiojamą lenkiškąją maldaknygę. Taip daryti ragino lenkų dvasininkai, kurie rūpinosi daugiau nutautinimu negu religijos mokymu. Kad šitokia veikla buvo įprastas reiškinys, yra daugybė pavyzdžių. Lietuvių šviesuomenės, kuri būtų galėjusi pasipriešinti tokiai politikai neturtingame Vilniaus krašte, buvo maža, o lietuvių kunigai buvo siunčiami į nelietuviškas parapijas. Kaip lenkų dvasininkija apaštalavo lietuviškose parapijose, liudijo seneliai, nemokėję nė žodžio lenkiškai, bet kalbėję lenkiškus poterius. Kai ilgainiui lietuviai pradėjo priešintis lenkinimui per bažnyčią, prasidėjo žiauri kova dėl lietuviškų pamokslų ir maldų. Ta kova primena savo metu siautusius katalikų ir protestantų religinius karus. Tik tų karų tikslas čia buvo kitas – ne religija, bet kalba. Yra žinoma, kad lenkiškoji lietuviškų parapijų dvasininkija kurstė brolį prieš brolį ir palaikė bažnytinius sąmyšius, organizuojamus lenkų naudai. Tose suirutėse kovojo tie patys lietuviai, kurių vieną dalį kunigija jau buvo aplenkinusi, kitos dar nespėjusi.

- Eugeniusz Römer (2001). ""Apie lietuvių ir lenkų santykius" (translation of "Zdziejów Romeriow na Litwie. Pasmo czynnośći ciągem lat idące...")". Lietuvos Bajoras (in Lithuanian). 5: 18–20. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

Tai jokiu būdu nelietė tautinio lietuvių atgimimo gerųjų pusių, kultūros ir švietimo kėlimo, o daugiau tik tam tikrus šio judėjimo ,,perlenkimus", dažnai juokingus, o lenkų atžvligiu net agresyvius...

- Eugeniusz Römer (2001). ""Apie lietuvių ir lenkų santykius" (translation of "Zdziejów Romeriow na Litwie. Pasmo czynnośći ciągem lat idące...")". Lietuvos Bajoras (in Lithuanian). 5: 18. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

Arba štai: bažnyčiose kovojant už neginčijamas lietuvių kalbos teises, kai kurie lietuvių kunigai buvo verčiami vyti nuo klausyklų tuos, kurie norėjo atlikti išpažintį lenkų kalba arba per papildomas pamaldas buvo atsisakoma per amžius jose giedamų lenkiškų giesmių ar Evangelijos lenkų kalba.

- Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (October 2006). ""Antypolski tekst K. Garsvy" (Anti-Polish text by K. Garsva)". Commentary on K.Garsva article "Kiedy na Wileńszczyźnie będzie wprowadzone zarządzanie bezpośrednie? (When Vilnius region will have direct self-government?)" in Lietuvos Aidas, 11 -12.10". Media zagraniczne o Polsce (Foreign Media on Poland) (in Polish). XV (200/37062). Retrieved 2006-01-20.

- Paweł Cieplak. "Polsko-litewskie stosunki (Polish-Lithuanian affairs)". Lithuanian Portal (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2009-05-05. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- Leonardas Vilkas, LITEWSKA, ŁOTEWSKA I ESTOŃSKA DROGA DO NIEPODLEGŁOŚCI I DEMOKRACJI: PRÓBA PORÓWNANIA (Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian Way to Independence: An Attempt to Compare, on homepage of Jerzy Targalski

- Donskis, Leonidas (2001). Identity and Freedom: Mapping Nationalism and Social Criticism in Twentieth Century Lithuania. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-0415270861.

According to Professor Zigmas Zinkevicius, the former minister of education and science of Lithuania, Lithuanian Poles living in the Vilnius region are, in fact, Polonised Lithuanians. In his opinion, they can have no awareness of who they are because, once assimilated, these Lithuanian Poles/Polonised Lithuanians lost their original identity. The minister concludes that it is every dedicated Lithuanian’s duty to educate and re-Lithuanianise those people who are incapable of understanding where they truly belong.

- Lazdiņa, Sanita; Marten, Heiko F., eds. (2019). Multilingualism in the Baltic States Societal Discourses and Contact Phenomena. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156. ISBN 978-1137569134.

- Moore, Irina (2019). "Linguistic landscape as an arena of conflict. Language removal, exclusion, and ethnic idenitity construction in Lithuania (Vilnius)". In Evans, Matthew; Jeffries, Lesley; O'Driscoll, Jim (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Language in Conflict (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 387. ISBN 978-0429058011.

- "Kolejna grzywna za tabliczki. Nie ma nowego "rekordu"..." Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "Third Opinion on Lithuania adopted on 28 November 2013". Council of Europe, Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. 10 October 2014: 24–25. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Fourth Opinion on Lithuania - adopted on 30 May 2018". Council of Europe, Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: 25–26. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Kara powyżej 40 tys. litów za dwujęzyczne tabliczki". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- More than 90 percent of Polish schools in Lithuania took part in the strike

- "LLRA rengs lenkiškų ir rusiškų mokyklų streiką" (in Lithuanian). 15min.lt. August 28, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2016.