Stacking window manager

A stacking window manager (also called floating window manager) is a window manager that draws all windows in a specific order, allowing them to overlap, using a technique called painter's algorithm. All window managers that allow the overlapping of windows but are not compositing window managers are considered stacking window managers, although it is possible that not all use exactly the same methods. Other window managers that are not considered stacking window managers are those that do not allow the overlapping of windows, which are called tiling window managers.[1]

Stacking window managers allow windows to overlap by drawing them one at a time. Stacking, or repainting (in reference to painter's algorithm) refers to the rendering of each window as an image, painted directly over the desktop, and over any other windows that might already have been drawn, effectively erasing the areas that are covered. The process usually starts with the desktop, and proceeds by drawing each window and any child windows from back to front, until finally the foreground window is drawn.[2]

The order in which windows are to be stacked is called their z-order.

Limitations

Stacking is a relatively slow process, requiring the redrawing of every window one-by-one, from the rear-most and outer-most to the front most and inner-most. Many stacking window managers don't always redraw background windows. Others can detect when a redraw of all windows is required, as some applications request stacking when their output has changed. Re-stacking is usually done through a function call to the window manager, which selectively redraws windows as needed. For example, if a background window is brought to the front, only that window should need to be redrawn.

A well-known disadvantage of stacking is that when windows are painted over each other, they actually end up erasing the previous contents of whatever part of the screen they are covering. Those windows must be redrawn when they are brought to the foreground, or when visible parts of them change. When a window has changed or when its position on the screen has changed, the window manager will detect this and may re-stack all windows, requiring that each window redraw itself, and pass its new appearance along to the window manager before it is drawn. When an application stops responding, it may be unable to redraw itself, which sometimes causes the area within the window frame to retain images of other windows when it is brought to the foreground. This problem is commonly seen on Windows XP and earlier, as well as some X window managers.

Another serious limitation that affects almost all stacking window managers is that they are often severely limited in the degree to which the interface can be accelerated by a graphics processing unit (GPU), and very little can be done about this.

Avoiding limitations

Some technological advances have been able to reduce or remove some of the disadvantages of stacking. One possible solution to the limited availability of hardware acceleration is to treat a single foreground window as a special case, rendering it differently from other windows.

This does not always require a redesign of the window manager because a foreground window is drawn last, in a known location on the screen, and is not covered by any other windows. Therefore, it can be easily isolated on the screen after it has been drawn. For one, since we know where the foreground window is, when the screen raster reaches the graphics hardware, the area occupied by the foreground window can be easily replaced with an accelerated texture.

However, if the window manager is also able to supply an application with an updated image of what the screen looked like before the foreground window was drawn but after all other windows were already drawn more possibilities open up. This would allow the one window in the foreground to appear semi-transparent, by using the before image as a texture filter on the final output. This was possible in Windows XP with software included with many NVidia GeForce video cards as well as from third party sources, using a hardware texture overlay.[3]

Another method of lessening the limitations of stacking is through the use of a hardware overlay and chroma keying. Since the video hardware can draw on the outgoing screen, a window is drawn containing a known colour, which allows the video hardware to detect which parts of the window are showing and should be drawn on. 3D and 2D accelerated video and animation may be added to windows using this method.

Full screen video may also be considered a way of avoiding limitations imposed by stacking. Full screen mode temporarily suspends the need for any window management, allowing applications to have full access to the video card. Accelerated 3D games under Windows XP and earlier relied totally on this method, as these games would not have been possible to play in windowed mode. However technically this method has nothing to do with the window manager, and is simply a means of superseding it.

Hybrid window managers

Some window managers may be able to treat the foreground window in an entirely different way, by rendering it indirectly, and sending its output to the video card to be added to the outgoing raster. While this technique may be possible to accomplish within some stacking window managers, it is technically compositing, with the foreground window and the screen raster being treated the same way two windows would be in a compositing window manager.

As described earlier, we might have access to a slightly earlier stage of stacking where the foreground window has not been drawn yet. Even if it is later drawn and set to the video card, it is still possible to simply overwrite it entirely at the hardware level with the slightly out of date version, and then create the composite without even having to draw in the original location of the window. This allows the foreground window to be transparent, or even three dimensional.

Unfortunately interacting with objects outside the original area of the foreground window might also be impossible, since the window manager would not be able to determine what the user is seeing, and would pass such mouse clicks to whatever programs occupied those areas of the screen during the last stacking event.

X Window System

Many windows managers under the X Window System provide stacking window functionality:

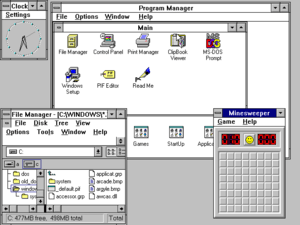

Microsoft Windows

Microsoft Windows 1.0 displayed windows using a tiling window manager. In Windows 2.0, it was replaced with a stacking window manager, which allowed windows to overlap. Microsoft kept the stacking window manager up through Windows XP, which presented severe limitations to its ability to display hardware-accelerated content inside normal windows. Although it was technically possible to produce some visual effects using third-party software.[3] From Windows Vista onward, a new compositing window manager is the default on compatible systems.[4]

History

- 1970s: The Xerox Alto which contained the first working commercial GUI used a stacking window manager.[5]

- Early 1980s: The Xerox Star, successor to the Alto, used tiling for most main application windows, and used overlapping only for dialogue windows removing the need for full stacking.[6]

- The Classic Mac OS was one of the earliest commercially successful examples of a GUI which used stacking windows.

- GEM 1.1 predated Microsoft Windows and used stacking, allowing all windows to overlap.[7] As a result of a lawsuit by Apple, GEM was forced to remove the stacking capabilities.[8]

- Amiga OS contains an early example of a highly advanced stacking window manager.

References

- "How-to: Picking a Window Manager in Linux". Engadget.

- "Painter's Algorithm". medialab.di.unipi.it.

- "TweakGuides.com - Nvidia GeForce Tweak Guide". www.tweakguides.com.

- "Desktop Window Manager - Windows applications". docs.microsoft.com.

- Lineback, Nathan. "The Xerox Alto". toastytech.com.

- Lineback, Nathan. "The Xerox Star". toastytech.com.

- Lineback, Nathan. "GEM 1.1 screenshots". Toastytech.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-25. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- Lineback, Nathan. "GEM 2.0 Screen Shots". Toastytech.com. Archived from the original on 2019-08-22. Retrieved 2016-08-01.