Lewisite

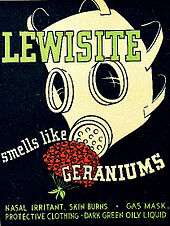

Lewisite (L) is an organoarsenic compound. It was once manufactured in the U.S., Japan, Germany[2] and the Soviet Union[3] for use as a chemical weapon, acting as a vesicant (blister agent) and lung irritant. Although colorless and odorless, impure samples of lewisite are a yellow, brown, violet-black, green, or amber oily liquid with a distinctive odor that has been described as similar to geraniums.[4][5]

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

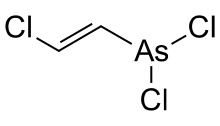

2-chloroethenylarsonous dichloride | |||

| Other names

2-chloroethenyldichloroarsine 2-chlorovinyldichloroarsine Chlorovinylarsine dichloride Dichloro(2-chlorovinyl)arsine | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| MeSH | lewisite | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2810 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C2H2AsCl3 | |||

| Molar mass | 207.32 g/mol | ||

| Density | 1.89 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −18 °C (0 °F; 255 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 190 °C (374 °F; 463 K) | ||

| Vapor pressure | 0.58 mmHg (25 °C) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Chemical reactions

The compound is prepared by the addition of arsenic trichloride to acetylene in the presence of a suitable catalyst:

- AsCl3 + C2H2 → ClCHCHAsCl2 (Lewisite)

Lewisite, like other arsenous chlorides, hydrolyses in water to form hydrochloric acid and chlorovinylarsenous oxide (a less-powerful blister agent):[5]

- ClCHCHAsCl2 + 2 H2O → ClCHCHAs(OH)2 + 2 HCl

This reaction is accelerated in alkaline solutions, and forms acetylene and trisodium arsenate.[5]

Lewisite will also react with metals to form hydrogen gas. It is combustible, but difficult to ignite.[5]

Mechanism of action

Lewisite is a suicide inhibitor of the E3 component of pyruvate dehydrogenase. As an efficient method to produce ATP, pyruvate dehydrogenase is involved in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. The latter subsequently enters the TCA cycle. Peripheral nervous system pathology usually arises from Lewisite exposure as the nervous system essentially relies on glucose as its only catabolic fuel.[6]

It can easily penetrate ordinary clothing and latex rubber gloves. Upon skin contact it causes immediate stinging, burning pain and itching that can last for 24 hours. Within minutes, a rash develops and the agent is absorbed through the skin. Large, fluid-filled blisters (similar to those caused by mustard gas exposure) develop after approximately 12 hours and cause pain for 2–3 days.[4][5] These are severe chemical burns and begin with small blisters in the red areas of the skin within 2–3 hours and grow worse, encompassing the entire red area, for the ensuing 12–18 hours after initial exposure. Liquid lewisite has faster effects than lewisite vapor.[5] Sufficient absorption can cause deadly liver necrosis.

Those exposed to lewisite can develop refractory hypotension (low blood pressure) known as Lewisite shock, as well as some features of arsenic toxicity.[7] Lewisite causes physical damage to capillaries, which then become leaky, meaning that there is not enough blood volume to maintain blood pressure, a condition called hypovolemia. When the blood pressure is low, the kidneys may not receive enough oxygen and can be damaged.[5]

Inhalation, the most common route of exposure, causes a burning pain and irritation throughout the respiratory tract, nosebleed (epistaxis), laryngitis, sneezing, coughing, vomiting, difficult breathing (dyspnea), and in severe cases of exposure, can cause fatal pulmonary edema, pneumonitis, or respiratory failure. Ingestion results in severe pain, nausea, vomiting, and tissue damage.[4][5] The results of eye exposure can range from stinging, burning pain and strong irritation to blistering and scarring of the cornea, along with blepharospasm, lacrimation, and edema of the eyelids and periorbital area. The eyes can swell shut, which can keep the eyes safe from further exposure. The most severe consequences of eye exposure to lewisite are globe perforation and blindness.[5] Generalised symptoms also include restlessness, weakness, hypothermia and low blood pressure.

It is possible that Lewisite may be a carcinogen: arsenic is categorized as a respiratory carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, though it has not been confirmed that lewisite is a carcinogen.[8]

Lewisite causes damage to the respiratory tract at levels lower than the odor detection threshold; early tissue damage is fairly noticeable due to the pain it causes.[5]

Treatment

British anti-lewisite, also called dimercaprol, is the antidote for lewisite. It can be injected to prevent systemic toxicity, but will not prevent injury to the skin, eyes, or mucous membranes. Chemically, dimercaprol binds to the arsenic in lewisite. It is contraindicated in those with peanut allergies.[5]

Other treatment for lewisite exposure is primarily supportive. First aid of lewisite exposure consists of decontamination and irrigation of any areas that have been exposed. Other basic first aid can be used as necessary, such as airway management, assisted ventilation, and monitoring of vital signs. In an advanced care setting, supportive care can include fluid and electrolyte replacement. Because the tube may injure or perforate the esophagus, gastric lavage is contraindicated.[5]

Long-term effects

From one acute exposure, someone who has inhaled lewisite can develop chronic respiratory disease; eye exposure to lewisite can cause permanent visual impairment or blindness.[5]

Chronic exposure to lewisite can cause arsenic poisoning (due to its arsenic content) and development of a lewisite allergy. It can also cause various long-term illnesses or permanent damage to organs, depending on where the exposure has occurred, including conjunctivitis, aversion to light (photophobia), visual impairment, double vision (diplopia), tearing (lacrimation), dry mucous membranes, garlic breath, burning pain in the nose and mouth, toxic encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, nausea, vomiting, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchitis, dermatitis, skin ulcers, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma.[5]

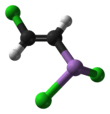

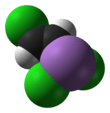

Chemical composition

The material "lewisite" may be a mixture of various numbers of vinylchloride groups on the arsenic chloride: lewisite itself (2-chlorovinylarsonous dichloride), along with bis(2-chlorovinyl)arsinous chloride (lewisite 2) and tris(2-chlorovinyl)arsine (lewisite 3).[9] In addition, there are sometimes isomeric impurities: lewisite itself is mostly trans-2-chlorovinylarsonous dichloride, but the cis stereoisomer and the constitutional isomer (1-chlorovinylarsonous dichloride) may also be present.[10]

Experimental and computational studies both find that the trans-2-chloro isomer is the most stable, and that the carbon–arsenic bond has a conformation in which the lone pair on the arsenic is approximately aligned with the vinyl group.[10]

History

Lewisite was first synthesised in 1904 by Julius Arthur Nieuwland during studies for his PhD.[11][12][13] Within his doctoral thesis he described a reaction between acetylene and arsenic trichloride, which led to the formation of lewisite.[14] Exposure to the resulting compound made Nieuwland so ill he was hospitalized for a number of days.[12]

Lewisite is named after the US chemist and soldier Winford Lee Lewis (1878–1943).[15] In 1918 Dr John Griffin (Julius Arthur Nieuwland's thesis advisor) drew Lewis's attention to Nieuwland's thesis at Maloney Hall, a chemical laboratory at The Catholic University of America, Washington D.C.[16] Lewis then attempted to purify the compound through distillation but found that the mixture exploded on heating until it was washed with HCl.[16]

Lewisite was developed into a secret weapon (at a facility located in Cleveland, Ohio (The Cleveland Plant) at East 131st Street and Taft Avenue[15][17]) and given the name "G-34" (which had previously been the code for mustard gas) in order to confuse its development with mustard gas.[18] Production began at a plant in Willoughby, Ohio on November 1, 1918.[19] It was not used in World War I, but experimented with in the 1920s as the "Dew of Death".[20]

After World War I, the US became interested in lewisite because it was not flammable. It had the military symbol of "M1" up into World War II, when it was changed to "L". Field trials with lewisite during World War II demonstrated that casualty concentrations were not achievable under high humidity due to its rate of hydrolysis and its characteristic odor and lacrymation forced troops to don masks and avoid contaminated areas. The United States produced about 20,000 tons of lewisite, keeping it on hand primarily as an antifreeze for mustard gas or to penetrate protective clothing in special situations.

It was replaced by the mustard gas variant HT (a 60:40 mixture of sulfur mustard and O Mustard), and declared obsolete in the 1950s. It is effectively treated with British anti-lewisite (dimercaprol). Most stockpiles of lewisite were neutralised with bleach and dumped into the Gulf of Mexico,[21] but some remained at the Deseret Chemical Depot located outside of Salt Lake City, Utah,[22] although as of January 18, 2012 all U.S stockpiles were destroyed.

Producing or stockpiling lewisite was banned by the Chemical Weapons Convention. When the convention entered force in 1997, the parties declared world-wide stockpiles of 6,747 tonnes of lewisite. As of December 2015, 98% of these stockpiles had been destroyed.[23]

In 2001, lewisite was found in a World War I weapons dump in Washington, D.C.[24]

Controversy over Japanese deposits of lewisite in China

In mid-2006, China and Japan were negotiating disposal of stocks of lewisite in northeastern China, left by Japanese military during World War II. Residents of China have died over the past twenty years from accidental exposure to these stockpiles.[25]

See also

References

- Lewisite I - Compound Summary, PubChem.

- Mitchell, Jon (27 July 2013). "A drop in the ocean: the sea-dumping of chemical weapons in Okinawa" – via Japan Times Online.

- "Russia Completes Destruction of First 10 Tons of Lewisite - Analysis - NTI". www.nti.org.

- U.S. National Research Council, Committee on Review and Evaluation of the Army Non-Stockpile Chemical Materiel Disposal Program (1999). Disposal of Chemical Agent Identification Sets. National Academies Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-309-06879-7.

- "CDC - The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database: Blister Agent: LEWISITE (L) - NIOSH". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- Berg, J.; Tymoczko, J. L.; Stryer, L. (2007). Biochemistry (6th ed.). New York: Freeman. pp. 494–495. ISBN 978-0-7167-8724-2.

- Chauhan, S.; Chauhan, S.; D’Cruz, R.; Faruqi, S.; Singh, K. K.; Varma, S.; Singh, M.; Karthik, V. Chemical warfare agents. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 26, 113-122

- Doi, M.; Hattori, N.; Yokoyama, A.; Onari, Y.; Kanehara, M.; Masuda, K.; Tonda, T.; Ohtaki, M.; Kohno, N. Effect of Mustard Gas Exposure on Incidence of Lung Cancer: A Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 2011, 173, 659-666.

- McNutt, Patrick M.; Tracey L., Hamilton (2015). "Ocular toxicity of chemical warfare agents". Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents. Academic Press. pp. 535–555.

- Urban, Joseph J.; von Tersch, Robert L. (1999). "Conformational analysis of the isomers of lewisite". J. Phys. Org. Chem. 12: 95–102. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1395(199902)12:2<95::AID-POC91>3.0.CO;2-V.

- Julius Arthur Nieuwland (1904) Some Reactions of Acetylene, Ph.D. thesis, University of Notre Dame (Notre Dame, Indiana).

- Vilensky, J. A. (2005). Dew of Death - The Story of Lewisite, America's World War I Weapon of Mass Destruction. Indiana University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0253346126.

- Vilensky, J. A.; Redman, K. (2003). "British Anti-Lewisite (Dimercaprol): An Amazing History". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 41 (3): 378–383. doi:10.1067/mem.2003.72. PMID 12605205.

- Vilensky, J. "Father Nieuwland and the 'Dew of Death'".

- "Deadliest Poison Discovered By An American". Early County News. May 29, 1919. p. 7. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Vilensky, J. A. (2005). Dew of Death - The Story of Lewisite, America's World War I Weapon of Mass Destruction. Indiana University Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0253346126.

- Upton native's role was the best defense; WWI masks thwarted Archived December 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Joel A. Vilensky, Dew of Death: The Story of Lewisite, America's World War I Weapon of Mass Destruction (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2005), page 36.

- Vilensky, J. A. (2005). Dew of Death - The Story of Lewisite, America's World War I Weapon of Mass Destruction. Indiana University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0253346126.

- Tabangcura, D. Jr.; Daubert, G. P. "British anti-Lewisite Development". Molecule of the Month. University of Bristol School of Chemistry.

- Code Red - Weapons of Mass Destruction Online Resources; - Blister Agents

- "Commander: World is safer with chemical stockpile gone".

- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (30 November 2016). "Annex 3". Report of the OPCW on the Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction in 2015 (Report). p. 42. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Tucker, J. B. (2001). "Chemical weapons: Buried in the backyard" (pdf). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 57 (5): 51–56. doi:10.2968/057005014.

- Abandoned Chemical Weapons (ACW) in China Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine