Siberian crane

The Siberian crane (Leucogeranus leucogeranus), also known as the Siberian white crane or the snow crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae, the cranes. They are distinctive among the cranes, adults are nearly all snowy white, except for their black primary feathers that are visible in flight and with two breeding populations in the Arctic tundra of western and eastern Russia. The eastern populations migrate during winter to China while the western population winters in Iran and formerly, in Bharatpur, India .

| Siberian crane | |

|---|---|

| A captive individual in a zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Gruidae |

| Genus: | Leucogeranus Bonaparte, 1855 |

| Species: | L. leucogeranus |

| Binomial name | |

| Leucogeranus leucogeranus (Pallas, 1773) | |

| |

| Migration routes, breeding and wintering sites | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Among the cranes, they make the longest distance migrations. Their populations, particularly those in the western range, have declined drastically in the 20th century due to hunting along their migration routes and habitat degradation. The world population was estimated in 2010 at about 3,200 birds, mostly belonging to the eastern population with about 95% of them wintering in the Poyang Lake basin in China, a habitat that may be altered by the Three Gorges Dam. In western Siberia there are only around ten of these cranes in the wild.

Taxonomy and systematics

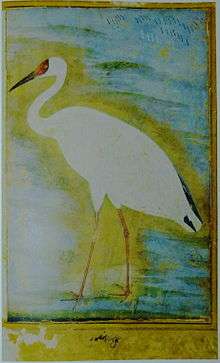

The Siberian crane was formally described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1773 and given the binomial name Grus leucogeranus.[2][3] The specific epithet is derived from the classical Greek words leukos for "white" and geranos for a "crane".[4] Ustad Mansur, a 17th-century court artist and singer of Jahangir, had illustrated a Siberian crane about 100 years earlier.[5] The genus Megalornis was used for the cranes by George Robert Gray and this species was included in it, while Richard Bowdler Sharpe suggested a separation from Grus and used the genus Sarcogeranus.[6][7][8] The Siberian crane lacks the complex tracheal coils found in most other cranes but shares this feature with the wattled crane. The unison call differed from that of most cranes and some authors suggested that the Siberian crane belonged in the genus Bugeranus along with the wattled crane. Comparisons of the DNA sequences of cytochrome-b however suggest that the Siberian crane is basal among the Gruinae and the wattled crane is retained as the sole species in the genus Bugeranus and placed as a sister to the Anthropoides cranes.[9][10]

A molecular phylogenetic study published in 2010 found that the genus Grus, as then defined, was polyphyletic.[11] In the resulting rearrangement to create monophyletic genera, the Siberian crane was moved to the resurrected genus Leucogeranus.[12] The genus Leucogeranus had been introduced by the French biologist Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1855.[13]

Description

Adults of both genders have a pure white plumage except for the black primaries, alula and primary coverts. The fore-crown, face and side of head is bare and brick red, the bill is dark and the legs are pinkish. The iris is yellowish. Juveniles are feathered on the face and the plumage is dingy brown. There are no elongated tertial feathers as in some other crane species.[14] During breeding season, both the male and female cranes are often seen with mud streaking their feathers. They dip their beaks in mud and smear it on their feathers. The call is very different from the trumpeting of most cranes and is a goose-like high pitched whistling toyoya. They typically weigh 4.9–8.6 kg (11–19 lb) and stand about 140 cm (55 in) tall. The wingspan is 210–230 cm (83–91 in) and length is 115–127 cm (45–50 in). Males are on average larger than females.[14][15][16][17][18][19] There is a single record of an outsized male of this species weighing 15 kg (33 lb).[20]

Distribution and habitat

The breeding area of the Siberian crane formerly extended between the Urals and Ob river south to the Ishim and Tobol rivers and east to the Kolyma region. The populations declined with changes in landuse, the draining of wetlands for agricultural expansion and hunting on their migration routes. The breeding areas in modern times are restricted to two widely disjunct regions. The western area in the river basins of the Ob, Konda and Sossva and to the east a much larger population in Yakutia between the Yana and the Alazeya rivers.[16] Like most cranes, the Siberian crane inhabits shallow marshlands and wetlands and will often forage in deeper water than other cranes. They show very high site fidelity for both their wintering and breeding areas, making use of the same sites year after year.[14] The western population winters in Iran and some individuals formerly wintered in India south to Nagpur and east to Bihar. The eastern populations winter mainly in the Poyang Lake area in China.[16]

Behaviour and ecology

Siberian cranes are widely dispersed in their breeding areas and are highly territorial. They maintain feeding territories in winter but may form small and loose flocks, and gather closer at their winter roosts. They are very diurnal, feeding almost all throughout the day. When feeding on submerged vegetation, they often immerse their heads entirely underwater. When calling, the birds stretch their neck forward.[16] The contexts of several calls have been identified and several of these vary with sex. Individual variation is very slight and most calls have a dominant frequency of about 1.4 kHz.[21] The unison calls, duets between paired males and female however are more distinctive with marked differences across pairs.[22] The female produces a higher pitched call which is the "loo" in the duetted "doodle-loo" call. Pairs will walk around other pairs to threaten them and drive them away from their territory.[16] In captivity, one individual was recorded to have lived for nearly 62 years[23] while another lived for 83 years.[24]

Feeding

These cranes feed mainly on plants although they are omnivorous. In the summer grounds they feed on a range of plants including the roots of hellebore (Veratrum misae), seeds of Empetrum nigrum as well as small rodents (lemmings and voles), earthworms and fish. They were earlier thought to be predominantly fish eating on the basis of the serrated edge to their bill, but later studies suggest that they take animal prey mainly when the vegetation is covered by snow. They also swallow pebbles and grit to aid in crushing food in their crop.[16] In their wintering grounds in China, they have been noted to feed to a large extent on the submerged leaves of Vallisneria spiralis.[25] Specimens wintering in India have been found to have mainly aquatic plants in their stomachs. They are however noted to pick up beetles and birds eggs in captivity.[26][27]

Breeding

Siberian cranes return to the Arctic tundra around the end of April and beginning of May.[28] The nest is usually on the edge of lake in boggy ground and is usually surrounded by water. Most eggs are laid in the first week of June when the tundra is snow free. The usual clutch is two eggs, which are incubated by the female after the second egg is laid. The male stands guard nearby. The eggs hatch in about 27 to 29 days. The young birds fledge in about 80 days. Usually only a single chick survives due to aggression between young birds. The population increase per year is less than 10%, the lowest recruitment rate among cranes. Their success in breeding may further be hampered by disturbance from reindeer and sometimes dogs that accompany reindeer herders.[16] Captive breeding was achieved by the International Crane Foundation at Baraboo after numerous failed attempts. Males often killed their mates and captive breeding was achieved by artificial insemination and the hatching of eggs by other crane species such as the Sandhill and using floodlights to simulate the longer daylengths of the Arctic summer.[29]

Migration

This species breeds in two disjunct regions in the arctic tundra of Russia; the western population along the Ob Yakutia and western Siberia. It is a long distance migrant and among the cranes, makes one of the longest migrations.[16] The eastern population winters on the Yangtze River and Lake Poyang in China, and the western population in Fereydoon Kenar in Iran. The central population, which once wintered in Keoladeo National Park,Bharatpur India, is extinct.

Status and conservation

The status of this crane is critical and the world population is estimated to be around 3200–4000, nearly all of them belonging to the eastern breeding population. Of the 15 crane species, this is one of the most threatened (the Whooping Crane of North America, with only 750 living individuals as of 2018, is rarer.) The western population has dwindled to 4 in 2002 and was thought to be extirpated but one 1 individual was seen in Iran in 2010. The wintering site at Poyang in China holds an estimated 98% of the population and is threatened by hydrological changes caused by the Three Gorges Dam and other water development projects.

Historic records from India suggest a wider winter distribution in the past including records from Gujarat, near New Delhi and even as far east as Bihar.[17][30] In 1974 as many as 75 birds wintered in Bharatpur and this declined to a single pair in 1992 and the last bird was seen in 2002.[31] In the 19th century, larger numbers of birds were noted to visit India.[32] They were sought after by hunters and specimen collectors. An individual that escaped from a private menagerie was shot in the Outer Hebrides in 1891.[33] The western population may even have wintered as far west as Egypt along the Nile.[34]

Satellite telemetry was used to track the migration of a flock that wintered in Iran. They were noted to rest on the eastern end of the Volga delta.[35] Satellite telemetry was also used to track the migration of the eastern population in the mid-1990s, leading to the discovery of new resting areas along the species' flyway in eastern Russia and China.[36] The Siberian crane is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies and is subject of the Memorandum of Understanding concerning Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane concluded under the Bonn Convention.

Significance in human culture

For Siberian natives – Yakuts and Yukaghirs - the white crane is a sacred bird associated with sun, spring and kind celestial spirits ajyy. In yakut epics Olonkho shamans and shamaness transform into white cranes.

References

- BirdLife International (2013). "Leucogeranus leucogeranus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 Nov 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 153.

- Pallas, Peter Simon (1773). Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs (in German). Volume 2. St. Petersburg: Academie der Wissenschaften. p. 714.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Divyabhanusinh (1987). "Record of two unique observations of the Indian cheetah in Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 84 (2): 269–274.

- Bowdler Sharpe, R (1893). "[Meeting notes]". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 1 (7): 37.

- Hartert, E (1922). Die Vogel der parlaarktischen Fauna. Band 3. Berlin: Verlag von R Friedlander and Sohn. pp. 1819–1820.

- Bowdler Sharpe, R (1894). Catalogue of the Fulicariae and Alectorides in the collection of the British Museum. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 261–262.

- Krajewski, C; JW Fetzner Jr. (1994). "Phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae) based on cytochrome-b DNA sequences" (PDF). The Auk. 111 (2): 351–365. doi:10.2307/4088599. JSTOR 4088599.

- Wood, D S (1979). "Phenetic relationships within the family Gruidae" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 91 (3): 384–399.

- Krajewski, C.; Sipiorski, J.T.; Anderson, F.E. (2010). "Mitochondrial genome sequences and the phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae)". Auk. 127 (2): 440–452. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09045.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Flufftails, finfoots, rails, trumpeters, cranes, limpkin". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1855). "Tableaux synoptiques de l'ordre des Hérons". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 40: 718–725 [720].

- Rasmussen, PC & Anderton, JC (2005). The Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. p. 138.

- Ali, S. & Ripley, S. D. (1980). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 2. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 144–146.

- Johnsgard, P. (1983). Cranes of the World (PDF). Indiana University Press. pp. 129–139. ISBN 978-0-253-11255-2.

- Baker, E. C. S. (1929). Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 6 (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. p. 53.

- Grus leucogeranus (2011).

- Grue de Sibérie. oiseaux.net

- Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- Bragina EV, Beme IR (2007). "[Sexual and individual differences in the vocal repertoire of adult Siberian Cranes (Grus leucogeranus, Gruidae)]" (PDF). Zoologičeskij žurnal (in Russian). 86 (12): 1468–1481. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-01.

- Bragina, EV & Irina R. Beme (2010). "Siberian crane duet as an individual signature of a pair: comparison of visual and statistical classification techniques". Acta Ethologica. 13 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1007/s10211-010-0073-6.

- Davis, Malcolm (1969). "Siberian Crane longevity" (PDF). Auk. 86 (2): 347.

- Temple, Stanley A. (1990). "How long do birds live The passenger pigeon" (PDF). 52 (3). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guofeng Wu; de Leeuw Jan; Skidmore Andrew K.; Prins Herbert H. T.; Best Elly P. H.; Yaolin Liu (2009). "Will the Three Gorges Dam affect the underwater light climate of Vallisneria spiralis L. and food habitat of Siberian crane in Poyang Lake?" (PDF). Hydrobiologia. 623: 213–222. doi:10.1007/s10750-008-9659-7.

- Quinton W. H. St. (1921). "The White Asiatic crane". The Avicultural Magazine. 12 (3): 33–34.

- Ellis, DH; Scott R. Swengel; George W. Archibald & Cameron B. Kepler (1998). "A sociogram for the cranes of the world" (PDF). Behavioural Processes. 43 (2): 125–151. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(98)00008-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- Bysykatova, IP; M. V. Vladimirtseva; N. N. Egorov & S. M. Sleptsov (2010). "Spring Migrations of the Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus) in Yakutia". Contemporary Problems of Ecology. 3 (1): 86–89. doi:10.1134/S1995425510010145.

- Stewart JM (2009). "The 'lily of birds': the success story of the Siberian white crane". Oryx. 21: 6–21. doi:10.1017/S0030605300020421.

- Blyth, Edward (1881). The natural history of the cranes. R. H. Porter. pp. 38–44.

- Sharma, B.K.; Kulshreshtha, Seema; Sharma, Shailja (2013). "Historical, Sociocultural, and Mythological Aspects of Faunal Conservation in Rajasthan". In Sharma, B.K.; Kulshreshtha, Seema; Rahmani, Asad R. (eds.). Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India: General Background and Ecology of Vertebrates. Springer. p. 201. ISBN 978-1461407997. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Siberian Crane Leucogeranus leucogeranus (Fig. 3.33) used to be the most charismatic and rare bird at Ghana or the Keoladeo National Park of Bharatpur. At one time, hundreds of “Sibes” used to winter in the Ghana Bird Sanctuary. Like white ghosts in the mist, they were lured by other north Indian wetlands from far and near. The “Sibes” used to visit Ghana from their breeding grounds in Siberia in search of food owing to the nonavailability of summer supplies due to extreme cold. No Siberian Crane was sighted in Bharatpur since 2003.

- Finn, Frank (1906). "How to know the Indian waders". Thacker, Spink and Co.: 82–83. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Clarke, WE (1892). "The reported occurrence of Grus leucogeranus Pallas, in the Outer Hebrides". The Annals of Scottish Natural History. 1 (1): 71–72.

- Provencal, P. & Sørensen, U. G. (1998). "Medieval record of the Siberian White Crane Grus leucogeranus in Egypt". Ibis. 140 (2): 333–335. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1998.tb04399.x.

- Kanai, Yutaka; Nagendran, Meenakshi; Ueta, Mutsuyuki; Markin, Yuri; Rinne, Juhani; Sorokin, Alexander G.; Higuchi, Hiroyoshi; Archibald, George W. (2002). "Discovery of breeding grounds of a Siberian Crane Grus leucogeranus flock that winters in Iran, via satellite telemetry". Bird Conservation International. 12 (4): 327–333. doi:10.1017/S0959270902002204.

- Kanai, Y.; Mutsuyuki, U.; Germogenov, N.; Negandran, M.; Mita, N.; Higuchi, H. (2002). "Migration routes and important resting areas of Siberian cranes Crus leucogeranus between northeastern Siberian and China as revealed by satellite tracking" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 106 (3): 339–346. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00259-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Siberian crane. |

- International Crane Foundation's Siberian crane page

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- Siberian Crane Flyway Coordination (SCFC) enhances communication among the large network of scientists, governmental agencies, biologists, private organizations, and citizens involved with Siberian crane conservation in Eurasia.

- Siberian Crane Wetland Project (SCWP) is a six-year effort to sustain the ecological integrity of a network of globally important wetlands in Asia that are of critical importance for migratory waterbirds and other wetland biodiversity, using the globally threatened Siberian crane as a flagship species.

- Online broadcasting of white cranes’ lives from the Oksk hatchery arose