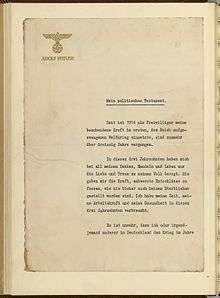

Last will and testament of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler signed his last will and testament in the Berlin Führerbunker on 29 April 1945, the day before he committed suicide with his wife Eva (nee) Braun.

The will was a short document stating that they had chosen death over capitulation, and that they were to be cremated; it named Martin Bormann as executor. The testament was in two parts. In the first, he denied charges of warmongering, expressed his thanks to Germany’s loyal citizens, and appealed to them to continue the struggle. In the second, he declared Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring to be traitors, and set out his plan for a new government under Karl Dönitz. Hitler’s secretary Traudl Junge recalled that he was reading from notes as he dictated the testament, and it is believed that Joseph Goebbels had helped him to write it.

Will

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The last will was a short document signed on 29 April at 04:00.[1] It acknowledged his marriage—but does not name Eva Braun—and that they choose death over disgrace of deposition or capitulation; and that their bodies were to be cremated. The will divided up Hitler's belongings as follows:[2]

- His art collection is left to "a gallery in my home town of Linz on the Danube";

- Objects of "sentimental value or necessary for the maintenance of a modest simple life" went to his relatives and his "faithful co-workers" such as his housekeeper Mrs. [Anni] Winter;

- Whatever else of value he possessed went to the National Socialist German Workers Party.

Martin Bormann was nominated as the will's executor. The will was witnessed by Bormann and Colonel Nicolaus von Below.[3]

Testament

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The last political testament was signed at the same time as Hitler's last will, 04:00 on 29 April 1945.[1] The first part of the testament talked of his motivations in the three decades since volunteering in World War I, repeated his claim that neither he "nor anyone else in Germany wanted the war in 1939", stated his reasons for his intention to commit suicide, and praised and expressed his thanks to the German people for their support and achievements.[4] Also included in the first testament are statements detailing his claim that he tried to avoid war with other nations and attributes responsibility for it to "international Jewry and its helpers".[5] He would not "forsake Berlin ... even though the forces were too small to hold out". Hitler expressed his intent to choose death rather than "fall into the hands of enemies" and the masses in need of "a spectacle arranged by Jews".[6] He concluded with a call to continue the "sacrifice" and "struggle".[6] He expressed hope for a renaissance of the National Socialist movement with the realization of a "true community of nations".[5]

The second part of his testament lays out Hitler's intentions for the government of Germany and the Nazi Party after his death and details who was to succeed him. He expelled Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring from the party and sacked him from all of his state offices. He also cancelled the 1941 decree naming Göring as his successor in the event of his death. To replace him, Hitler named Großadmiral Karl Dönitz as President of the Reich and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.[7] Reichsführer-SS and Interior Minister Heinrich Himmler was also expelled from the party and sacked from all of his state offices for attempting to negotiate peace with the western Allies without Hitler's "knowledge" and against permission.[6] Hitler declared both Himmler and Göring to be traitors.[8]

Hitler appointed the following as the new Cabinet and as leaders of the nation:[9]

- President of the Reich (Reichspräsident), Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces (Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht), Minister of War (Kriegsminister) and Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine): Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz

- Chancellor of the Reich (Reichskanzler): Dr. Joseph Goebbels

- Party Minister (Parteiminister): Martin Bormann

- Foreign Minister (Aussenminister): Arthur Seyss-Inquart

- Interior Minister (Innenminister): Gauleiter Paul Giesler

- Commander-in-Chief of the Army (Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres): Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner

- Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force (Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe): Field Marshal Robert Ritter von Greim

- Reichsführer-SS and Chief of Police (Reichsführer-SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei): Gauleiter Karl Hanke

- Minister of Economy (Wirtschaft): Walther Funk

- Minister of Agriculture (Landwirtschaft): Herbert Backe

- Minister of Justice (Justiz): Otto Thierack

- Minister of Culture (Kultur): Dr. Gustav Adolf Scheel

- Minister of Propaganda (Propaganda): Dr. Werner Naumann

- Minister of Finance (Finanzen): Johann Ludwig Graf Schwerin von Krosigk

- Minister of Labour (Arbeit): Dr. Theo Hupfauer

- Minister of Munitions (Rüstung): Karl-Otto Saur

- Director of the German Labour Front and member of the Cabinet (Leiter der Deutschen Arbeitsfront und Mitglied des Reichskabinetts: Reichsminister) Dr. Robert Ley

Witnessed by Joseph Goebbels, Martin Bormann, General Wilhelm Burgdorf, and General Hans Krebs.[1]

On the afternoon of 30 April, about a day and a half after he signed his last will and testament, Hitler and Braun committed suicide.[10] Within the next two days, Goebbels, Burgdorf and Krebs also committed suicide. Bormann committed suicide on 2 May to avoid capture by the Soviet Army forces encircling Berlin.[11]

Authorship

In his book The Bunker, James O'Donnell, after comparing the wording of Hitler's last testament to the writings and statements of both Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, concluded that Goebbels was at least partly responsible for helping Hitler to write it. Junge stated that Hitler was reading from notes when he dictated the testament after midnight on 29 April.[12]

Story of the documents

Three messengers were assigned to take the will and political testament out of the besieged Führerbunker to ensure their presence for posterity. The first messenger was deputy press attaché Heinz Lorenz. He was arrested by the British while traveling under an alias as a journalist from Luxembourg. He revealed the existence of two more copies and messengers: Willy Johannmeyer, Hitler's army adjutant, and Bormann's adjutant SS-Standartenführer Wilhelm Zander. Zander was using the pseudonym "Friedrich Wilhelm Paustin" to travel, and was shortly apprehended along with Johannmeyer in the American zone of occupation. Thus, two copies of the papers ended up in American hands, and one set in British hands. The texts of the documents were published widely in the American and British press by January 1946 but the British Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, considered restricting access to these documents. He feared they might become cult objects among the Germans. Since they were public knowledge already, the Americans did not share these concerns but nonetheless agreed to refrain from further publication of them. Hitler's testament and his marriage certificate were presented to U.S. President Harry S. Truman. One set was placed on public display at the National Archives in Washington for several years.[13]

Hitler's original last will and testament is currently housed in the security vault of the National Archives at College Park in Maryland.[14]

Aftermath

All four witnesses to the political testament died shortly afterwards. Goebbels and his wife committed suicide. Burgdorf and Krebs committed suicide together on the night of 1-2 May in the bunker. Bormann's exact time and place of death remain uncertain; his remains were discovered near the site of the bunker in 1972 and identified by DNA analysis in 1998. Therefore, he most likely died the same night trying to escape from the Führerbunker complex.[15]

In the Flensburg Government of Hitler's appointed successor as Reichspräsident Karl Dönitz, the depositions of Albert Speer and Franz Seldte were ignored (or the two ministers quickly reinstated). Neither former incumbent Joachim von Ribbentrop nor Hitler's appointee, Seyß-Inquart, held the post of Foreign Minister. The post was given to Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, who after Goebbels' suicide also became Leading Minister of the German Reich (Head of Cabinet, post equivalent to Chancellor).

Notes

- Kershaw 2008, p. 950.

- Hitler 1945a.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 948, 950.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 948.

- Hitler 1945b.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 949.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 949, 950.

- Evans 2008, p. 724.

- Hitler 1945b; NS-Archiv

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 953–955.

- Beevor 2002, pp. 381, 383, 387, 389.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 946.

- Eckert 2012, pp. 46–47.

- National Archives and Records Administration, "Annual Holdings Reports" (Volume 75), 13 Jun 2011

- Martin Bormann – in one of the 10 groups attempting to escape from the bunker complex – managed to cross the Spree. He was reported to have died a short distance from the Weidendammer bridge, his body was seen and identified by Arthur Axmann who followed the same route (Beevor 2002, p. 383)

References

- Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. London: Viking–Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eckert, Astrid M. (2012). The Struggle for the Files. The Western Allies and the Return of German Archives after the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0521880183.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich At War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hitler, Adolph (1945a). .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hitler, Adolph (1945b). .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "NS-Archiv: Adolf Hitler, Die Testamente". NS-Archiv (in German). Retrieved 5 June 2019.—The German version of the testament includes the fifteen other names only noted as "Here follow fifteen others" in the English translation published by the U.S. Government.

External links

- The Death of Hitler explains why Hitler had fallen out with Goering.

- Documents in the National Archives

- The Discovery of Hitlers wills