Alois Hitler

Alois Hitler Sr. (born Alois Schicklgruber; 7 June 1837 – 3 January 1903) was an Austrian civil servant and the father of the future dictator of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler.

Alois Hitler | |

|---|---|

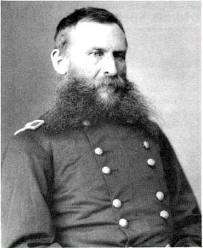

Alois Hitler Sr. in 1901 | |

| Born | Alois Schicklgruber 7 June 1837 |

| Died | 3 January 1903 (aged 65) |

| Resting place | Town Cemetery |

| Occupation | Customs officer |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | |

| Parent(s) | |

Alois Hitler was born illegitimately, and his paternity was never established. This led to claims that his wife Klara (Adolf's mother) may have been his cousin. It also meant that Adolf Hitler could not prove who his grandfather was and thus prove his own "Aryan descent". When Alois was promoted in the Customs service, he applied to be legitimised in the name of his stepfather Hiedler, which was entered in the register as 'Hitler', for unknown reasons.

Alois had a poor relationship with Adolf, whom he regularly punished severely.

Early life

Alois Hitler was originally born Alois Schicklgruber in the hamlet of Strones, a parish of Döllersheim in the Waldviertel of northwest Lower Austria; he was the son of a 42-year-old unmarried peasant, Maria Schicklgruber, whose family had lived in the area for generations. At his baptism in Döllersheim, the space for his father's name on the baptismal certificate was left blank and the priest wrote "illegitimate".[1][2][3] His mother cared for Alois in a house she shared with her elderly father, Johannes Schicklgruber.

Sometime later, Johann Georg Hiedler moved in with the Schicklgrubers; he married Maria when Alois was five. By the age of 10, Alois had been sent to live with Hiedler's brother, Johann Nepomuk Hiedler, who owned a farm in the nearby village of Spital (part of Weitra). Alois attended elementary school, and took lessons in shoemaking from a local cobbler. At the age of 13 he left the farm in Spital and went to Vienna as an apprentice cobbler, working there for about five years. In response to a recruitment drive by the Austrian government offering employment in the civil service to people from rural areas, Alois joined the frontier guards (customs service) of the Austrian Finance Ministry in 1855 at the age of 18.

Biological father

Historians have proposed various candidates as Alois's biological father: Johann Georg Hiedler, his brother Johann Nepomuk Hiedler (or Hüttler), and Leopold Frankenberger (whose actual existence has never been documented).[4] During his lifetime, Johann Georg Hiedler was the stepfather and posthumously legally declared birth father of Alois.[5] According to historian Frank McDonough, the most plausible theory is that Hiedler was actually the birth father. An explanation for Alois being sent to live on his uncle's farm as a child is that Hiedler and Maria were simply too poor to raise him, or could not raise him as well as his uncle, or perhaps Maria's health was in decline.

Historian Werner Maser suggests that Alois's father was Johann Nepomuk, Georg's brother and Hitler's step-uncle, who raised Alois through adolescence, and later willed him a considerable portion of his life savings, but never admitted publicly to being his real father. According to Maser, Nepomuk was a married farmer who had an affair and then arranged to have his single brother Hiedler marry Alois's mother Maria to provide a cover for Nepomuk's desire to assist and care for Alois, without upsetting his wife.[6] This assumes Hiedler was willing to marry Maria in this situation, and Adolf Hitler biographer Joachim Fest thinks this is too contrived and unlikely to be true.

Alois's son Adolf, following the rumours that his paternal grandfather was a Jew, in 1931 ordered the Schutzstaffel (SS) to investigate the alleged rumours regarding his ancestry; unsurprisingly, they found no evidence of any Jewish ancestors.[7] After the Nuremberg Laws came into effect in Nazi Germany, Hitler ordered the genealogist Rudolf Koppensteiner to publish a large illustrated genealogical tree showing his ancestry; this was published in the book Die Ahnentafel des Fuehrers ("The Pedigree of the Leader") in 1937, and concluded that Hitler's family were all Austrian Germans with no Jewish ancestry, and that Hitler had an unblemished "Aryan" pedigree.[8][9] As Alois himself legitimised Johann Georg Hiedler as his father and the priest changed this on his birth certificate in 1876, this was considered certified proof for Hitler's ancestry; thus Hitler was considered a "pure" Aryan.[8]

Although Johann Georg Hiedler was considered the officially accepted paternal grandfather of Adolf Hitler by the Third Reich, the question of who his grandfather was has caused much speculation and remains unknown.[10][11] German historian Joachim Fest wrote that:

The indulgence normally accorded to a man's origins is out of place in the case of Adolf Hitler, who made documentary proof of Aryan ancestry a matter of life and death for millions of people but himself possessed no such document. He did not know who his grandfather was. Intensive research into his origins, accounts of which have been distorted by propagandist legends and which are in any case confused and murky, has failed so far to produce a clear picture. National Socialist versions skimmed over the facts and emphasized, for example, that the population of the so-called Waldviertel, from which Hitler came, had been 'tribally German since the Migration of the Peoples', or more generally, that Hitler had 'absorbed the powerful forces of this German granite landscape into his blood through his father'.[12]

After the war, Adolf Hitler's former lawyer, Hans Frank, claimed that Hitler told him in 1930 that one of his relatives was trying to blackmail him by threatening to reveal his alleged Jewish ancestry.[13] Adolf Hitler asked Frank to find out the facts. Frank says he determined that at the time Maria Schicklgruber gave birth to Alois she was working as a household cook in the town of Graz, that her employers were a Jewish family named Frankenberger, and that her child might have been conceived out of wedlock with the family's 19-year-old son, Leopold Frankenberger.[14]

However, all Jews had been expelled from the province of Styria – which includes Graz – in the 15th century; they were not officially allowed to return until the 1860s, when Alois was around 30. Also, there is no evidence of a Frankenberger family living in Graz at that time. Scholars such as Ian Kershaw and Brigitte Hamann dismiss the Frankenberger hypothesis, which had only Frank's speculation to support it, as baseless.[15][16][17][18]

Kershaw cites several stories circulating in the 1920s about Hitler's alleged Jewish ancestry, including one about a "Baron Rothschild" in Vienna in whose household Maria Schicklgruber had worked for some time as a servant.[19] Kershaw discusses and also lists Hitler's family tree in his biography of Adolf Hitler and gives no support to the Frankenberger tale.[20] Further, Frank's story contains several inaccuracies and contradictions, such as he said "The fact that Adolf Hitler had no Jewish blood in his veins, seems, from what has been his whole manner, so blatant to me that it needs no further word",[21] also the statement Frank had made that Maria Schicklgruber came from "Leonding near Linz", when in fact she came from the hamlet of Strones, near the village of Döllersheim.[22]

In 2019, Leonard Sax published a scholarly paper titled "Aus den Gemeinden von Burgenland: revisiting the question of Adolf Hitler's paternal grandfather".[23] Sax showed that Hamann, Kershaw, and other leading historians relied, either directly or indirectly, on a single source for the claim that no Jews were living in Graz prior to 1856: that source was the Austrian historian Nikolaus von Preradovich, whom Sax showed was a fervent admirer of Adolf Hitler. Sax cited primary Austrian sources from the 1800s to demonstrate that there was in fact "eine kleine, nun angesiedelte Gemeinde" – "a small, now settled community" – of Jews living in Graz prior to 1856. Sax's article has been picked up by a number of news outlets[24] and Sax was interviewed by Eric Metaxas on this topic, on Metaxas' TV show.[25]

Ron Rosenbaum suggests that Frank, who had turned against Nazism after 1945 but remained an anti-Semitic fanatic, made the claim that Hitler had Jewish ancestry as a way of proving that Hitler was a Jew and not an Aryan.[26]

Early career

Alois Schicklgruber made steady progress in the semi-military profession of customs official. The work involved frequent reassignments and he served in a variety of places across Austria. By 1860, after five years of service, he reached the rank of Finanzwach-Oberaufseher (Revenue guard superintendent). By 1864, after special training and examinations, he had advanced further and was serving in Linz, Austria. He later became an inspector of customs posted at Braunau am Inn in 1875. He eventually rose to full inspector of customs and could go no higher because he lacked the necessary school degrees.

Change of surname

As a rising young junior customs official, he used his birth name of Schicklgruber, but in mid-1876, 39 years old and well established in his career, he asked permission to use his stepfather's family name. He appeared before the parish priest in Döllersheim and asserted that his father was Johann Georg Hiedler, who had married his mother and now wished to legitimize him. Three relatives appeared with him as witnesses, one of whom was Johann Nepomuk, Hiedler's brother. The priest agreed to amend the birth certificate, the civil authorities automatically processed the church's decision and Alois Schicklgruber had a new name. The official change, registered at the government office in Mistelbach in 1877, transformed him into "Alois Hitler". It is not known who decided on the spelling of Hitler instead of Hiedler. Johann Georg's brother was sometimes known by the surname Hüttler.

Bradley F. Smith states that Alois Schicklgruber openly admitted having been born out of wedlock before and after the name change.[28] Alois may have been influenced to change his name for the sake of legal expediency. Historian Werner Maser claims that in 1876, Franz Schicklgruber, the administrator of Alois's mother's estate, transferred a large sum of money (230 gulden) to him.[6]

Supposedly, Johann Georg Hiedler, who died in 1857, relented on his deathbed and left an inheritance to his illegitimate stepson (Alois) together with his name.[29]

Some Schicklgrubers remain in the Waldviertel.

Personal life

Illegitimate daughter

In early 1869, Alois Hitler had an affair with Thekla Penz (born 24 September 1844) of Leopoldstein, Arbesbach in the district of Zwettel, Lower Austria. This led to the birth of Theresia Penz on 31 October 1869. Thekla later married a man by the name of Horner, while Theresia married Johan Ramer and gave birth to at least six children, while living in the town of Schwertberg.

Early married life

Alois Hitler was 36 years old in 1873 when he married for the first time. Anna Glasl-Hörer was a wealthy, 50-year-old daughter of a customs official. She was infirm when they married and was either an invalid or became one shortly afterwards.

Not long after marrying his first wife, Anna, Alois began an affair with Franziska "Fanni" Matzelsberger, one of the young female servants employed at the Pommer Inn, house number 219, in the city of Braunau am Inn, where he was renting the top floor as a lodging. Smith states that Alois had numerous affairs in the 1870s, resulting in his wife initiating legal action; on 7 November 1880 Alois and Anna separated by mutual agreement. The 19-year-old Matzelsberger became the 43-year-old Hitler's girlfriend.

In 1876, three years after Alois married Anna, he had hired Klara Pölzl as a household servant. She was the 16-year-old granddaughter of Hitler's step-uncle (and possible father or biological uncle) Nepomuk. If Nepomuk was Hitler's father, Klara was Alois's half-niece. If his father was Johann Georg, she was his first cousin once removed. Matzelsberger demanded that the "servant girl" Klara find another job, and Hitler sent Pölzl away.

On 13 January 1882, Matzelsberger gave birth to Hitler's illegitimate son, also named Alois, but since they were not married, the child's last name was Matzelsberger, making him "Alois Matzelsberger". Alois Hitler kept Matzelsberger as his wife while his lawful wife (Anna) grew sicker and died on 6 April 1883. The next month, on 22 May at a ceremony in Braunau with fellow custom officials as witnesses, Alois, 45, married Matzelsberger, 21. He then legitimized his son as Alois Hitler Jr.[30] Alois's second child, Angela, was born on 28 July 1883.

Alois was secure in his profession and no longer an ambitious climber. Historian Alan Bullock described him as "hard, unsympathetic and short-tempered".[31] Matzelsberger, still only 23, acquired a lung disorder and became too ill to function. She was moved to Ranshofen, a small village near Braunau. During the last months of Matzelsberger's life, Klara Pölzl returned to Alois's home to look after the invalid and the two children (Alois Jr. and Angela).[32] Matzelsberger died in Ranshofen on 10 At 1884 at the age of 23. After the death of his second wife, Pölzl remained in his home as housekeeper.[32]

Marriage to Klara Pölzl and family life

Pölzl was soon to be pregnant by Alois Hitler. Smith writes that if Hitler had been free to do as he wished, he would have married Pölzl immediately but because of the affidavit concerning his paternity, Hitler was now legally Pölzl's first cousin once removed, too close to marry. He submitted an appeal to the church for a humanitarian waiver.[33] Permission came, and on 7 January 1885 a wedding was held at Hitler's rented rooms on the top floor of the Pommer Inn. A meal was served for the few guests and witnesses. Hitler then went to work for the rest of the day. Even Klara found the wedding to be a short ceremony.[34]

On 17 May 1885, four months after the wedding, the new Frau Klara Hitler gave birth to her first child, Gustav. In 1886, she gave birth to a daughter, Ida. In 1887 Otto was born, but died days later.[35] During the winter of 1887–1888, diphtheria struck the Hitler household, resulting in the deaths of both Gustav (8 December) and Ida (2 January).

On 20 April 1889, she gave birth to another son, future dictator of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler. Adolf was a sickly child, and his mother fretted over him. Alois was 51 when he was born, and had little interest in child-rearing; he left it all to his wife. When not at work he was either in a tavern or busy with his hobby, keeping bees. Alois was transferred from Braunau to Passau. He was 55, Klara 32, Alois Jr. 10, Angela 9, and Adolf was three years old.

Beginning on 1 August, the family lived at Theresienstr. 23. One month after Alois accepted a better paying position in Linz, on 1 April 1893, his wife and the children moved to a second floor room on Kapuzinerstr. 31.[36] Klara had just given birth to Edmund, so it was decided she and the children would stay in Passau for the time being.[37] On 21 January 1896, Paula, Adolf's younger sister, was born. She was the last child of Alois Hitler and Klara Pölzl. Alois was often home with his family. He had five children ranging in age from infancy to 14. Edmund (the youngest of the boys) died of measles on 2 February 1900.

Alois Hitler wanted his son Adolf to seek a career in the civil service. However, Adolf had become so alienated from his father that he was repulsed by his wishes. He sneered at the thought of a lifetime spent enforcing petty rules. Alois tried to browbeat his son into obedience, while Adolf did his best to be the opposite of whatever his father wanted.[38]

Robert G. L. Waite noted, "Even one of his closest friends admitted that Alois was 'awfully rough' with his wife [Klara] and 'hardly ever spoke a word to her at home'." If Alois was in a bad mood, he picked on the older children or Klara herself, in front of them. William Patrick Hitler says that he had heard from his father, Alois Jr., that Alois Hitler Sr. used to beat his children.[27] After Hitler and his eldest son Alois Jr. had a climactic and violent argument, Alois Jr. left home, and the elder Alois swore he would never give the boy a penny of inheritance beyond what the law required. According to reports, Alois Hitler liked to lord it over his neighbors.[27]

Retirement and death

In February 1895, Alois Hitler purchased a house on a 3.6-hectare (9-acre) plot in Hafeld near Lambach, approximately 50 kilometres (30 mi) southwest of Linz. The farm was called the Rauscher Gut. He moved his family to the farm and retired on 25 June 1895 at the age of 58, after 40 years in the customs service. He found farming difficult; he lost money, and the value of the property declined.

On the morning of 3 January 1903, Alois went to the Gasthaus Wiesinger (no. 1 Michaelsbergstrasse, Leonding) as usual to drink his morning glass of wine. He was offered the newspaper and promptly collapsed. He was taken to an adjoining room and a doctor was summoned, but he died at the inn, probably from a pleural hemorrhage. Adolf Hitler, who was 13 when his father died, wrote in Mein Kampf that he died of a "stroke of apoplexy".[39] In his book, The Young Hitler I Knew, Hitler's childhood friend August Kubizek recalled, "When the fourteen-year-old [sic] son saw his dead father he burst out into uncontrollable weeping."

Removal of tombstone

On 28 March 2012, by the account of Kurt Pittertschatscher, the pastor of the parish, the tombstone marking Alois Hitler's grave and that of his wife Klara, in Town Cemetery in Leonding, was removed by a descendant. The descendant is said to be an elderly female relative of Alois Hitler's first wife, Anna, who has also given up any rights to the rented burial plot. The plot was covered in white gravel and a tree which has since been removed. It is not known whether the remains of Adolf Hitler's parents are still interred there.[40]

In popular culture

In films, Alois Hitler has been portrayed by:

- Helmut Griem in the Tales of the Unexpected episode "Genesis and Catastrophe" (1980)

- James Remar in The Twilight Zone episode "Cradle of Darkness" (2002)

- Ian Hogg in Hitler: The Rise of Evil (2003)

See also

References

Notes

- Toland, John Adolf Hitler, Doubleday & Company, 1976, pp. 3–5.

- Shirer, William L The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Simon & Schuster, 1960, p. 7.

- Kershaw, Ian Hitler, 1889–1936: Hubris, WW Norton & Co, 2000, pp. 3–9

- Frank McDonough, Hitler and the rise of the Nazi Party, Pearson Education, 2003, p. 20.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler, 1889–1936: Hubris, W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, p. 4.

- Werner Maser – Hitler: Legend, Myth and Reality (in German, 1971; Penguin Books Ltd 1973 ISBN 0-06-012831-3)

- Fischel, Jack (1998). The Holocaust. Greenwood. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-313-29879-0.

- "Ancestry of Adolf Hitler". Wargs.com. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- Koppensteiner, Rudolf (1937). Die Ahnentafel des Führers - Rudolf Koppensteiner - Google Books. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- "Lineage of Adolf Hitler - Density inbreeding". Der Spiegel.

- "Hitler - No proof of Aryan descent". Der Spiegel.

It is clear that Adolf Hitler proof of Aryan ancestry, he demanded to most Germans, for his own person could hardly have been able to provide. His paternal grandfather is unknown.

- Joachim C. Fest (1999-05-07). The Face of the Third Reich. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-306-80915-6.

- Rosenbaum, Ron Explaining Hitler, New York: Random House 1998, pp. 20–22.

- Rosenbaum, Ron Explaining Hitler, New York: Random House 1998, pp. 20–21.

- Brigitte Hamann; Hans Mommsen (3 August 2010). Hitler's Vienna: A Portrait of the Tyrant as a Young Man. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-1-84885-277-8.

- "Hatte Hitler jüdische Vorfahren?". Holocaust-Referenz.

- "Was Hitler part Jewish?". The Straight Dope. April 9, 1993.

- "Was Hitler Jewish?". Jewish Virtual Library.

- "Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris". New York Times.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler, A Biography, W. W. Norton & Company, 2008, pp. 2–4.

- "Holocaust-Referenz : Hatte Hitler jüdische Vorfahren?". H-ref.de. Retrieved 2012-07-24.

- Rosenbaum, Ron Explaining Hitler, New York: Random House 1998 p. 21.

- "Aus den Gemeinden von Burgenland". Sage. doi:10.1177/0047244119837477. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Altmetric listing of news articles". Sage.

- "Eric Metaxas interview with Leonard Sax". Eric Metaxas show.

- Rosenbaum, Ron. Explaining Hitler, New York: Random House 1998 pp. 21, 30–31.

- "The Mind of Adolf Hitler", Walter C. Langer, New York 1972 p.115

- Smith, Bradley F. Adolf Hitler: His Family, Childhood and Youth. Hoover Institute, 1967 ISBN 0-8179-1622-9

- "The Mind of Adolf Hitler", Walter C. Langer, New York 1972 p.111

- ""Hitler As He Knows Himself", report by Walter Langer for the OSS". Nizkor.org. Archived from the original on 2017-07-22. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- Bullock, Alan Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, Harper&Row Publishers, 1962, p. 25

- "The Mind of Adolf Hitler", Walter C. Langer, New York 1972 p. 114

- Alois petitioned the church for an episcopal dispensation citing "bilateral affinity in the third degree touching the second" to describe his rather complicated family relationship to Klara. The local bishop apparently believed this relationship was too close to approve on his own authority, so he forwarded the petition to Rome on behalf of Alois, seeking instead a papal dispensation, which was approved before the birth of the couple's first child. See Rosenblum article.

- Payne, Robert (1973). The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler. New York: Praeger. p. 12.The marriage took place early in the morning, and Klara is said to have complained: "We were married at six o'clock in the morning, and my husband was already at work at seven."

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Anna Rosmus: Hitlers Nibelungen, Samples Grafenau 2015, p. 20f

- The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler, Robert Payne, 1973, p. 17

- Hamann, Brigitte (2010). Hitler's Vienna. New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-84885-277-8.

- Mein Kampf, by Adolf Hitler, 4%

- "Adolf Hitler parents' tombstone in Austria removed". BBC News. 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2014-06-15.

Bibliography

- Bullock, Alan (1953) Hitler: A Study in Tyranny ISBN 0-06-092020-3

- Fest, Joachim C. (1973) Hitler Verlag Ullstein. ISBN 0-15-141650-8

- Hamann, Brigitte Hitler's Vienna, Tauris Parke Paperbacks 2010 ISBN 978-1-84885-277-8

- Kershaw, Ian (1999) Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris New York:W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04671-0

- Langer, Walter C. (1972) The Mind of Adolf Hitler. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04620-7 ASIN: B000CRPF1K

- Payne, Robert (1973) The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler. Praeger. LCCN 72-92891

- Rosenbaum, Ron (1998) Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil New York: Random House. ISBN 0-670-82158-6

- Vermeeren, Marc (2007)De jeugd van Adolf Hitler 1889–1907 en zijn familie en voorouders. Soesterberg: Uitgeverij Aspekt. ISBN 978-90-5911-606-1

- Waite, Robert G. L. (1977) The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-06743-3

External links