Lassen Volcanic National Park

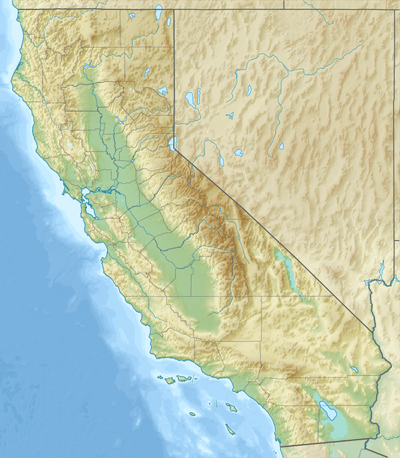

Lassen Volcanic National Park is an American national park in northeastern California. The dominant feature of the park is Lassen Peak, the largest plug dome volcano in the world and the southernmost volcano in the Cascade Range.[3] Lassen Volcanic National Park started as two separate national monuments designated by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907: Cinder Cone National Monument and Lassen Peak National Monument.[4]

| Lassen Volcanic National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

Lake Helen in Lassen Volcanic National Park | |

Location in California  Location in the United States | |

| Location | Shasta, Lassen, Plumas, and Tehama counties, California, United States |

| Nearest city | Redding and Susanville |

| Coordinates | 40°29′16″N 121°30′18″W |

| Area | 106,452 acres (430.80 km2)[1] |

| Established | August 9, 1916 |

| Visitors | 499,435 (in 2018)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Lassen Volcanic National Park |

.jpg)

The source of heat for the volcanism in the Lassen area is subduction of the Gorda Plate diving below the North American Plate off the Northern California coast.[5] The area surrounding Lassen Peak is still active with boiling mud pots, fumaroles, and hot springs.[6] Lassen Volcanic National Park is one of the few areas in the world where all four types of volcano can be found—plug dome, shield, cinder cone, and stratovolcano.[7]

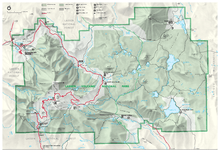

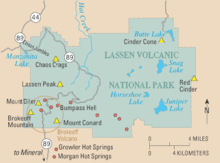

The park is accessible via State Routes 89 and 44. SR 89 passes north-south through the park, beginning at SR 36 to the south and ending at SR 44 to the north. SR 89 passes immediately adjacent to the base of Lassen Peak. There are five vehicle entrances to the park: the north and south entrances on SR 89; and unpaved roads entering at Drakesbad and Juniper Lake in the south, and at Butte Lake in the northeast. The park can also be accessed by trails leading in from the Caribou Wilderness to the east, as well as the Pacific Crest Trail, and two smaller trails leading in from Willow Lake and Little Willow Lake to the south.

The national park, which is near the cities of Redding and Susanville, is located in portions of Shasta, Lassen, Plumas, and Tehama counties.

The Lassen Chalet, a large lodge with concession facilities, was located near the southwest entrance, but was demolished in 2005. A new full-service visitor center in the same location opened to the public in 2008. The Lassen Ski Area was located near the lodge; it ceased operation in 1992 and all infrastructure has been removed.

History

Native Americans have inhabited the area since long before white settlers first saw Lassen. The natives knew that the peak was full of fire and water and thought it would one day blow itself apart.[8]

European immigrants in the mid-19th century used Lassen Peak as a landmark on their trek to the fertile Sacramento Valley. One of the guides to these immigrants was a Danish blacksmith named Peter Lassen, who settled in Northern California in the 1830s. Lassen Peak was named after him.[8] Nobles Emigrant Trail was later cut through the park area and passed Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds.

Inconsistent newspaper accounts reported by witnesses from 1850 to 1851 described seeing "fire thrown to a terrible height" and "burning lava running down the sides" in the area of Cinder Cone. As late as 1859, a witness reported seeing fire in the sky from a distance, attributing it to an eruption. Early geologists and volcanologists who studied the Cinder Cone concluded the last eruption occurred between 1675 and 1700. After the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) began reassessing the potential risk of other active volcanic areas in the Cascade Range. Further study of Cinder Cone estimated the last eruption occurred between 1630 and 1670. Recent tree-ring analysis has placed the date at 1666.

The Lassen area was first protected by being designated as the Lassen Peak Forest Preserve. Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone were later declared as U.S. National Monuments in May 1907 by President Theodore Roosevelt.[9]

Starting in May 1914 and lasting until 1921, a series of minor to major eruptions occurred on Lassen. These events created a new crater, and released lava and a great deal of ash. Fortunately, because of warnings, no one was killed, but several houses along area creeks were destroyed. Because of the eruptive activity, which continued through 1917, and the area's stark volcanic beauty, Lassen Peak, Cinder Cone and the area surrounding were declared a National Park on August 9, 1916.[8]

The 29-mile (47 km) Main Park Road was constructed between 1925 and 1931, just 10 years after Lassen Peak erupted. Near Lassen Peak the road reaches 8,512 feet (2,594 m), making it the highest road in the Cascade Mountains. It is not unusual for 40 ft (12 m) of snow to accumulate on the road near Lake Helen and for patches of snow to last into July.

In October 1972, a portion of the park was designated as Lassen Volcanic Wilderness by the US Congress (Public Law 92-511). The National Park Service seeks to manage the wilderness in keeping with the Wilderness Act of 1964, with minimal developed facilities, signage, and trails. The management plan of 2003 adds that, "The wilderness experience offers a moderate to high degree of challenge and adventure."[10]

In 1974, the National Park Service took the advice of the USGS and closed the visitor center and accommodations at Manzanita Lake. The Survey stated that these buildings would be in the way of a rockslide from Chaos Crags if an earthquake or eruption occurred in the area.[8] An aging seismograph station remains. However, a campground, store, and museum dedicated to Benjamin F. Loomis stands near Manzanita Lake, welcoming visitors who enter the park from the northwest entrance.

After the Mount St. Helens eruption, the USGS intensified its monitoring of active and potentially active volcanoes in the Cascade Range. Monitoring of the Lassen area includes periodic measurements of ground deformation and volcanic-gas emissions and continuous transmission of data from a local network of nine seismometers to USGS offices in Menlo Park, California.[11] Should indications of a significant increase in volcanic activity be detected, the USGS will immediately deploy scientists and specially designed portable monitoring instruments to evaluate the threat. In addition, the National Park Service (NPS) has developed an emergency response plan that would be activated to protect the public in the event of an impending eruption.

| Visitors to Lassen National Park by year[12] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Recreational visitors |

| 2016 | 536,068 |

| 2015 | 468,092 |

| 2014 | 432,977 |

| 2013 | 427,409 |

| 2012 | 407,653 |

| 2011 | 351,269 |

| 2010 | 384,570 |

| 2009 | 365,639 |

| 2008 | 377,361 |

| 2007 | 395,057 |

The NPS tracks visitors by counting vehicles entering the park via in-road inductive loops at all vehicle entrances. Buses and other non-reportable vehicles are subtracted from the vehicle count, which is then multiplied by three, an estimate of the number of visitors per vehicle.[13]

Geography and geology

The park is located near the northern end of the Sacramento Valley. The western part of the park features great lava pinnacles (huge mountains created by lava flows), jagged craters, and steaming sulfur vents. It is cut by glaciated canyons and is dotted and threaded by lakes and rushing clear streams.

The eastern part of the park is a vast lava plateau more than one mile (1.6 km) above sea level. Here, small cinder cones are found. (Fairfield Peak, Hat Mountain, and Crater Butte).[14] Forested with pine and fir, this area is studded with small lakes, but it boasts few streams. Warner Valley, marking the southern edge of the Lassen Plateau, features hot spring areas (Boiling Springs Lake, Devils Kitchen, and Terminal Geyser).[14] This forested, steep valley also has large meadows that have wildflowers in spring.

Lassen Peak is made of dacite,[15] an igneous rock, and is one of the world's largest plug dome volcanoes. It is also the southernmost non-extinct volcano of the Cascade Range (specifically, the Shasta Cascade part of the range). 10,457-foot (3,187 m) tall volcano sits on the north-east flank of the remains of Mount Tehama, a stratovolcano that was a thousand feet (305 m) higher than Lassen and 11 to 15 miles (18 to 24 km) wide at its base.[8] After emptying its throat and partially doing the same to its magma chamber in a series of eruptions, Tehama either collapsed into itself and formed a two-mile (3.2 km) wide caldera in the late Pleistocene or was simply eroded away with the help of acidic vapors that loosened and broke the rock, which was later carried away by glaciers.

Sulphur Works is a geothermal area in between Lassen Peak and Brokeoff Mountain that is thought to mark an area near the center of Tehama's now-gone cone. Other geothermal areas in the caldera are Little Hot Springs Valley, Diamond Point (an old lava conduit), and Bumpass Hell (see Geothermal areas in Lassen Volcanic National Park).

The magma that fuels the volcanoes in the park is derived from subduction off the coast of Northern California. Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds, located about 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Lassen Peak, is a cinder cone volcano and associated lava flow field that last erupted about 1650. It created a series of basaltic andesite to andesite lava flows known as the Fantastic Lava Beds.

There are four shield volcanoes in the park; Mount Harkness (southwest corner of the park), Red Mountain (at south-central boundary), Prospect Peak (in northeast corner), and Raker Peak (north of Lassen Peak). All of these volcanoes are 7,000–8,400 feet (2,133–2,560 m) above sea level and each is topped by a cinder cone volcano.

During ice ages, glaciers have modified and helped to erode the older volcanoes in the park. The center of snow accumulation and therefore ice radiation was Lassen Peak, Red Mountain, and Raker Peak. These volcanoes thus show more glacial scarring than other volcanoes in the park.

Despite not having any glaciers currently, Lassen Peak does have 14 permanent snowfields.[16]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Lassen Volcanic National Park has a Mediterranean-influenced warm-summer Humid continental climate (Dsb). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center at 6736 ft (2053 m) elevation is 6b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -0.2 °F (-17.9 °C).[17]

Since the entire park is located at medium to high elevations, the park generally has cool-cold winters and warm summers below 7,500 feet (2,300 m). Above this elevation, the climate is harsh and cold, with cool summer temperatures. Precipitation within the park is high to very high due to a lack of a rain shadow from the Coast Ranges. The park gets more precipitation than anywhere else in the Cascades south of the Three Sisters. Snowfall at the new visitor center near the southwest entrance at 6,700 feet (2,040 m) is around 430 inches (1,100 cm) despite facing east. Up around Lake Helen, at 8,200 feet (2,500 m) the snowfall is around 600–700 inches (1,500–1,800 cm), making it probably the snowiest place in California. In addition, Lake Helen gets more average snow accumulation than any other recording station located near a volcano in the Cascade range, with a maximum of 178 inches (450 cm).[18] Snowbanks persist year-round.

| Climate data for Manzanita Lake, elevation: 5,863 ft (1,787 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

68 (20) |

71 (22) |

78 (26) |

88 (31) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

88 (31) |

78 (26) |

68 (20) |

97 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.0 (5.0) |

42.7 (5.9) |

44.9 (7.2) |

51.2 (10.7) |

60.6 (15.9) |

69.9 (21.1) |

79.1 (26.2) |

77.6 (25.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

60.5 (15.8) |

47.2 (8.4) |

41.9 (5.5) |

57.4 (14.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 20.2 (−6.6) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

34.5 (1.4) |

40.9 (4.9) |

45.6 (7.6) |

44.1 (6.7) |

40.5 (4.7) |

33.9 (1.1) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −13 (−25) |

−11 (−24) |

−7 (−22) |

−2 (−19) |

11 (−12) |

20 (−7) |

30 (−1) |

28 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

10 (−12) |

2 (−17) |

−13 (−25) |

−13 (−25) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.28 (160) |

5.19 (132) |

5.26 (134) |

3.55 (90) |

2.80 (71) |

1.59 (40) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.57 (14) |

1.22 (31) |

2.97 (75) |

5.17 (131) |

5.74 (146) |

40.7 (1,033.1) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 36.5 (93) |

33.9 (86) |

34.9 (89) |

22.8 (58) |

7.5 (19) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

3.1 (7.9) |

18.2 (46) |

31.0 (79) |

189.4 (481.66) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[19] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center, elevation: 6,867 ft (2,093 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38.4 (3.6) |

39.9 (4.4) |

43.6 (6.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

58.5 (14.7) |

67.5 (19.7) |

74.8 (23.8) |

74.4 (23.6) |

68.2 (20.1) |

57.0 (13.9) |

44.4 (6.9) |

37.3 (2.9) |

54.6 (12.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.0 (−1.1) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

33.6 (0.9) |

38.9 (3.8) |

46.3 (7.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

61.5 (16.4) |

60.4 (15.8) |

55.5 (13.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

35.2 (1.8) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

43.5 (6.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

21.4 (−5.9) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

34.1 (1.2) |

40.2 (4.6) |

48.1 (8.9) |

46.3 (7.9) |

42.7 (5.9) |

34.0 (1.1) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

32.3 (0.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 16.19 (411) |

12.94 (329) |

13.60 (345) |

7.99 (203) |

5.37 (136) |

2.93 (74) |

0.71 (18) |

0.98 (25) |

2.24 (57) |

6.49 (165) |

14.52 (369) |

17.83 (453) |

101.79 (2,585) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.4 | 68.3 | 64.2 | 61.3 | 53.2 | 45.8 | 37.9 | 33.6 | 34.6 | 49.7 | 66.1 | 70.0 | 54.4 |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[20] | |||||||||||||

Plants

According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. Potential natural vegetation Types, Lassen Volcanic National Park has a Red Fir, aka Abies magnifica (7) potential vegetation type with a California Conifer Forest (2) potential vegetation form.[21]

Lying at the northern end of the Sierra Nevada forests ecoregion, Lassen Volcanic National Park preserves a landscape nearly as it existed before Euro-American settlement: its 27,130 acres (10,980 ha) of old growth include all of its major forest types.[22][23]

At elevations below 6,500 feet the dominant vegetation community is the mixed conifer forest. Ponderosa and Jeffrey Pines, Sugar Pine, and White Fir form the forest canopy for this rich community that also includes species of manzanita, gooseberry, and ceanothus. Common wildflowers include iris, spotted coralroot, pyrola, violets, and lupin.[24]

Above the mixed-conifer forest is the major community of the Red Fir forest. Between elevations of 6,500 and 8,000 feet, Red Fir, Western White Pine, Mountain Hemlock, and Lodgepole Pine dominate a community less diverse than the mixed-conifer forest. Common plants include satin lupine, woolly mule's-ears and pinemat manzanita.[24]

Subalpine areas include the upper limit for the growth of standing trees. From 8,000 feet to treeline, plants are fewer in overall number with exposed patches of bare ground providing a harsh environment. Rock spirea, lupin, Indian paintbrush, and penstemon are a few of the rugged members of this community. Trees in this community include Whitebark Pine and Mountain Hemlock.[24]

Wildlife

Species that are typically found in these forested areas are black bear, red fox, mule deer, marten, cougar, brown creeper, a variety of chipmunk species, raccoon, mountain chickadee, pika, a variety of squirrel species, white-headed woodpecker, coyote, bobcat, weasel, a variety of mouse species, long-toed salamander, skunk, and a wide variety of bat species.[25]

Geology

Formation of basement rocks

In the Cenozoic, uplifting and westward tilting of the Sierra Nevada along with extensive volcanism generated huge lahars (volcanic-derived mud flows) in the Pliocene which became the Tuscan Formation. This formation is not exposed anywhere in the national park but it is just below the surface in many areas.

Also in the Pliocene, basaltic flows erupted from vents and fissures in the southern part of the park. These and later flows covered increasingly large areas and built a lava plateau. In the later Pliocene and into the Pleistocene, these basaltic flows were covered by successive thick and fluid flows of andesite lava, which geologists call the Juniper lavas and the Twin Lakes lavas. The Twin Lakes lava is black, porphyritic and has abundant xenocrysts of quartz (see Cinder Cone).

Another group of andesite lava flows called the Flatiron, erupted during this time and covered the southwestern part of the park's area. The park by this time was a relatively featureless and large lava plain. Subsequently, the Eastern basalt flows erupted along the eastern boundary of what is now the park, forming low hills that were later eroded into rugged terrain.

Volcanoes rise

Pyroclastic eruptions then started to pile tephra into cones in the northern area of the park.

Mount Tehama (also known as Brokeoff Volcano) rose as a stratovolcano in the southwestern corner of the park during the Pleistocene. It was made of roughly alternating layers of andesitic lavas and tephra (volcanic ash, breccia, and pumice) with increasing amounts of tephra with elevation. At its height, Tehama was probably about 11,000 feet (3,400 m) high.

Approximately 350,000 years ago its cone collapsed into itself and formed a two-mile (3.2 km) wide caldera after it emptied its throat and partially did the same to its magma chamber in a series of eruptions. One of these eruptions occurred where Lassen Peak now stands, and consisted of fluid, black, glassy dacite, which formed a layer 1,500 feet (460 m) thick (outcroppings of which can be seen as columnar rock at Lassen's base).

During glacial periods (ice ages) of the present Wisconsinan glaciation, glaciers have modified and helped to erode the older volcanoes in the park, including the remains of Tehama. Many of these glacial features, deposits and scars, however, have been covered up by tephra and avalanches, or were destroyed by eruptions.

Roughly 27,000 years ago (older data gave an age of 18,000 years), Lassen Peak started to form as a dacite lava dome quickly pushed its way through Tehama's destroyed north-eastern flank. As the lava dome pushed its way up, it shattered overlaying rock, which formed a blanket of talus around the emerging volcano. Lassen rose and reached its present height in a relatively short time, probably in as little as a few years. Lassen Peak has also been partially eroded by Ice Age glaciers, at least one of which extended as much as 7 miles (11 km) from the volcano itself.

Since then, smaller dacite domes formed around Lassen. The largest of these, Chaos Crags, is just north of Lassen Peak. Phreatic (steam explosion) eruptions, dacite and andesite lava flows and cinder cone formation have persisted into modern times.

There are active hot springs and mud pots in the Lassen area. Some of these springs are the site of occurrence of certain extremophile micro-organisms, that are capable of surviving in extremely hot environments.[26]

See also

Footnotes

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Topinka, Topink (May 11, 2005). "Lassen Peak Volcano, California". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Lee, Robert F (2001). "The Story of the Antiquities Act". Chapter 8: The Proclamation of National Monuments Under the Antiquities Act, 1906–1970

- Lynch, David K. "Volcanoes and their relationship to plate tectonics". SanAndreasFault.org. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Clynne, Michael A; Janik, Cathy J; Muffler, LJP. "Hot Water in Lassen Volcanic National Park: Fumaroles, Steaming Ground, and Boiling Mudpots" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- "HOTSPOT: California On The Edge: Cascade Range Volcanoes". California Academy of Sciencies. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Geology of National Parks, pp. 542–46.

- Geology of U.S. Parklands, p. 154.

- "NPS 2003 General Management Plan, Wilderness Zone" (PDF). Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- USGS: Volcano Hazards of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Area, California

- "Lassen Volcanic NP". National Park Service Public Use Statistics Office. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- "Public Use Reporting and Counting Instructions". Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- "Geology Fieldnotes for Lassen Volcanic National Park California". Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- MacDonald, Gordon A.; Katsura, Takashi (1965). "Eruption of Lassen Peak, Cascade Range, California, in 1915: Example of Mixed Magmas". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 76 (5): 475–481. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1965)76[475:EOLPCR]2.0.CO;2.

- "Glaciers Online". Archived from the original on March 5, 2007.

- "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "Cascade Snow". Skimountaineer.com. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- "MANZANITA LAKE, CALIFORNIA - Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". www.prism.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "U.S. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions)". Data Basin. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Franklin, Jerry, F; Fites-Kaufmann, Jo Ann (1996). "Status of the Sierra Nevada, Ch. 21" (III: Biological and Physical Elements of the Sierra Nevada ed.). Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project. Final Report to Congress: 627–671. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bolsinger, Charles L.; Waddell, Karen L. (1993). "Area of old-growth forests in California, Oregon, and Washington" (PDF). United States Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Resource Bulletin PNW-RB-197. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Plants". United States National Park Service: Lassen Volcanic National Park. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- Sahagunu, Louis (July 5, 2019). "A deadly fungus is killing millions of bats in the U.S. Now it's in California". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Extremophile. eds. E.Monosson and C.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC

References

![]()

- Harris, Ann G.; Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D., Tuttle (2004). Geology of National Parks (6th ed.). Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 0-7872-9971-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Volcano Hazards of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Area, California, U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 022-00, Online version 1.0 (adapted public domain text; accessed September 25, 2006)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lassen Volcanic National Park. |

- "Lassen Volcanic National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- "Volcano Hazards of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Area". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- "USGS: Geology of Lassen Volcanic National Park". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- "Historic images of Lassen National Park". University of California. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- "A Fateful Year at Cinder Cone", NASA Earth Observatory, history of the 1666 eruption. Retrieved October 17, 2018.