Three Sisters (Oregon)

The Three Sisters are closely spaced volcanic peaks in the U.S. state of Oregon. They are part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, a segment of the Cascade Range in western North America extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. Each more than 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in elevation, they are the third-, fourth- and fifth-highest peaks in Oregon. Located in the Three Sisters Wilderness at the boundary of Lane and Deschutes counties and the Willamette and Deschutes national forests, they are about 10 miles (16 km) south of the nearest town, Sisters. Diverse species of flora and fauna inhabit the area, which is subject to frequent snowfall, occasional rain, and extreme temperature variation between seasons. The mountains, particularly South Sister, are popular destinations for climbing and scrambling.

| Three Sisters | |

|---|---|

The Three Sisters, looking north | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | |

| Prominence | 5,588 feet (1,703 m) (South Sister) [6] |

| Listing | US most prominent peaks, 85th (South Sister) |

| Coordinates | 44°06′12″N 121°46′09″W [7] |

| Geography | |

Three Sisters Location in Oregon | |

| Location | Lane and Deschutes counties, Oregon, U.S. |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS South Sister and North Sister |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Quaternary |

| Mountain type | Two stratovolcanoes (South, Middle) and one shield volcano (North) |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 440 CE[8] |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hiking or scrambling, plus glacier travel on some routes[9] |

Although they are often grouped together as one unit, the three mountains have their own individual geology and eruptive history. Neither North Sister nor Middle Sister has erupted in the last 14,000 years, and it is considered unlikely that either will ever erupt again. South Sister last erupted about 2,000 years ago and could erupt in the future, threatening life within the region. After satellite imagery detected tectonic uplift near South Sister in 2000, the United States Geological Survey improved monitoring in the immediate area.

Geography

The Three Sisters are at the boundary of Lane and Deschutes counties and the Willamette and Deschutes national forests in the U.S. state of Oregon, about 10 miles (16 km) south of the nearest town of Sisters.[10] The three peaks are the third-, fourth-, and fifth-highest in Oregon,[11] and contain 16 named glaciers.[12] Their ice volume totals 5.6 billion cubic feet (160×106 m3).[13] The Sisters were named Faith, Hope and Charity by early settlers, but are now known as North Sister, Middle Sister and South Sister, respectively.[14][15]

Wilderness

The Three Sisters Wilderness covers an area of 281,190 acres (1,137.9 km2), making it the second-largest wilderness area in Oregon. Designated by the United States Congress in 1964, it borders the Mount Washington Wilderness to the north and shares its southern edge with the Waldo Lake Wilderness. The area includes 260 miles (420 km) of trails and many forests, lakes, waterfalls, and streams, including the source of Whychus Creek.[16] The Three Sisters and nearby Broken Top account for about a third of the Three Sisters Wilderness, and this area is known as the Alpine Crest Region. Rising from about 5,200 feet (1,600 m) to 10,358 feet (3,157 m) in elevation, the Alpine Crest Region features the wilderness area's most-frequented glaciers, lakes, and meadows.[17]

Physical geography

Weather varies greatly in the area due to the rain shadow caused by the Cascade Range. Air from the Pacific Ocean rises over the western slopes, which causes it to cool and dump its moisture as rain (or snow in the winter). Precipitation increases with elevation. Once the moisture is wrung from the air, it descends on the eastern side of the crest, which causes the air to be warmer and drier. On the western slopes, precipitation ranges from 80 to 125 inches (200 to 320 cm) annually, while precipitation over the eastern slopes varies from 40 to 80 inches (100 to 200 cm) in the east. Temperature extremes reach 80 to 90 °F (27 to 32 °C) in summers and −20 to −30 °F (−29 to −34 °C) during the winters.[18]

The Three Sisters have about 130 snowfields and glaciers ranging in altitude from 6,742 to 10,308 feet (2,055 to 3,142 m) with a cumulative surface area of about 2,500 acres (10 km2).[19] The Linn and Villard Glaciers are north of the North Sister Summit, while the Thayer Glacier is on its eastern slope. The Collier Glacier is nestled between North Sister and Middle Sister and flows to the northwest. The Renfrew and Hayden Glaciers are the northwestern and northeastern slopes of Middle Sister, respectively, while the Diller Glacier is on its southeastern slope. The Irving, Carver and Skinner Glaciers lie between Middle Sister and South Sister. Finally, around the summit of South Sister, in a clockwise direction, are the Prouty, Lewis, Clark, Lost Creek, and Eugene Glaciers.[19] The Collier Glacier, despite a 4,900-foot (1,500 m) retreat and a 64% loss of its surface area between 1910 and 1994, is generally considered to be the largest of the Three Sisters at 160 acres (0.65 km2).[19][20] Eliot Glacier on Mount Hood is now two-and-a-half times larger than the Collier Glacier.[19] According to sources, the Prouty Glacier is sometimes considered to be larger than the Collier glacier.[21]

When Little Ice Age glaciers retreated during the 20th century, water filled in the spaces left behind, forming moraine-dammed lakes, which are more common in the Three Sisters Wilderness than anywhere else in the contiguous United States.[22] The local area has a history of flash floods, including an event on October 7, 1966, caused by a sudden avalanche; this flash flood reached the Cascade Lakes Scenic Byway. Concerned about the hazard of similar flooding events, scientists in the 1980s from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) identified that Carver Lake on South Sister could flood and breach its natural dam, producing a large mudflow that could endanger wilderness visitors and the town of Sisters. Studies at Collier Lake and Diller Lake suggested that both had breached their dams in the early 1940s and in 1970, respectively. Other moraine-dammed lakes within the wilderness area include Thayer Lake on North Sister's east flank and four members of the Chambers Lakes group between Middle and South Sister.[23]

Before settlement of the area at the end of the 19th century, wildfires frequently burned through the local forests, especially the ponderosa pine forests on the eastern slopes. Due to fire suppression over the past century, the forests have become overgrown, and at higher elevations, they are further susceptible to summertime fires, which threaten surrounding life and property. In the 21st century, wildfires have been larger and more common in the Deschutes National Forest.[24] In September 2012, a lightning strike caused a fire that burned 41 square miles (110 km2) in the Pole Creek area within the Three Sisters Wilderness, leaving the area closed until May 2013.[25] In August 2017, officials closed 417 square miles (1,080 km2) in the western half of the Three Sisters Wilderness,[26] including 24 miles (39 km) of the Pacific Crest Trail,[27] to the public because of 11 lightning-caused fires, including the Milli Fire.[26][28] As a result of the increasing incidence of fires, public officials have factored the role of wildfire into planning,[24] including organizing prescribed fires with scientists to protect habitats at risk while minimizing adverse effects on air quality and environmental health.[29]

Geology

The Three Sisters join several other volcanoes in the eastern segment of the Cascade Range known as the High Cascades, which trends north–south.[30] Constructed towards the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, these mountains are underlain by more ancient volcanoes that subsided due to parallel north–south faulting in the surrounding region.[31]

Part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc and the Cascade Range, each of the three volcanoes formed at different times from several variable magmatic sources. The amount of rhyolite present in the lavas of the younger two mountains is unusual relative to nearby peaks.[14][30] The Three Sisters form the leading edge of a rhyolitic crustal-melting anomaly, which might be explained by a combination of mantle flow (movement of Earth's solid silicate mantle layer caused by convection currents) and decompression that has generated similar melting and rhyolitic volcanism nearby for the past 16 million years.[32] Like other Cascade volcanoes, the Three Sisters were fed by magma chambers produced by the subduction of the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate under the western edge of the North American tectonic plate.[30]

The three mountains were also shaped by the changing climate of the Pleistocene epoch, during which multiple glacial periods occurred and glacial advance eroded the mountains.[33]

The Three Sisters form the center of a region of closely grouped volcanic peaks. This is in contrast to the typical 40-to-60-mile (64 to 97 km) spacing between volcanoes elsewhere in the Cascades.[34] Among the most active volcanic areas in the Cascades and one of the most densely populated volcanic centers in the world,[35] the Three Sisters region includes nearby peaks such as Belknap Crater, Mount Washington, Black Butte, and Three Fingered Jack to the north, and Broken Top and Mount Bachelor to the south.[34][36] Most of the surrounding volcanoes consist of mafic (basaltic) lavas;[36] only South and Middle Sister have an abundance of silicic rocks such as andesite, dacite, and rhyodacite.[37] Mafic magma is less viscous; it produces lava flows and is less prone to explosive eruptions than silicic magma.[38]

The region was active in the Pleistocene, with eruptions between about 650,000 and about 250,000 years ago from an explosively active complex known as the Tumalo volcanic center.[39] This area features andesitic and mafic cinder cones such as Lava Butte,[40] as well as rhyolite domes. Cinder cones accumulate from the airfall of many pyroclastic rock fragments of various sizes,[41] while the viscous rhyolite domes extrude onto the surface like toothpaste.[42]

The Tumalo volcano spread ignimbrites and plinian deposits in ground eruptions across the area, similar to the eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii. These deposits spread from Tumalo to the town of Bend.[43] Basaltic lava flows from North Sister overlay the youngest Tumalo pyroclastic deposits, indicating that North Sister was active more recently than 260,000 years ago.[44]

North Sister

North Sister, also known as "Faith", is the oldest and most highly eroded of the three, with zigzagging rock pinnacles between glaciers.[37] It is a shield volcano that overlays a more ancient shield volcano named Little Brother.[45] North Sister is 5 miles (8 km) wide,[45] and its summit elevation is 10,090 feet (3,075 m).[4][5] Consisting primarily of basaltic andesite, it has a more mafic composition than the other two volcanoes.[46] Its deposits are rich in palagonite and red and black cinders, and they are progressively more iron-rich the younger they are.[45] North Sister's lava flows demonstrate similar compositions throughout the mountain's long eruptive history.[46] The oldest lava flows on North Sister have been dated to roughly 311,000 years ago,[44] though the oldest reliably dated deposits are approximately 119,000 years old.[37] Estimates place the volcano's last eruption at 46,000 years ago, in the Late Pleistocene.[47][48]

North Sister possesses more dikes than any similar Cascade peak, caused by lava intruding into pre-existing rocks. Many of these dikes were pushed aside by the intrusion of a 980-foot (300 m)-wide volcanic plug. The dikes and plug were exposed by centuries of erosion.[46] At one point, the volcano stood more than 11,000 feet (3,400 m) high, but erosion reduced this volume by a quarter to a third.[49] The plug is now exposed and forms North Sister's summits at Prouty Peak and the South Horn.[50]

Middle Sister

Middle Sister, also known as "Hope", is a basaltic stratovolcano that has also erupted more-viscous andesite, dacite, and rhyodacite.[51] The smallest and least studied of the three, Middle Sister began eruptive activity 48,000 years ago,[52] and it was primarily built by eruptions occurring between 25,000 and 18,000 years ago.[44] One of the earliest major eruptive events (about 38,000 years ago) produced the rhyolite of Obsidian Cliffs on the mountain's northwestern flank.[53] Thick and rich in dacite, the flows extended from the northern and southern sides. They stand in contrast to older, andesitic lava remains that reach as far as 4.3 miles (7 km) from its base.[54]

With an elevation of 10,052 feet (3,064 m),[2][3] the mountain is cone-shaped. The eastern side has been heavily eroded by glaciation, while the western face is mostly intact.[49] Of the Three Sisters, Middle Sister has the largest ice cover.[13] The Hayden and Diller glaciers continue to cut into the east face, while the Renfrew Glacier sits on the northwestern slope.[54] The large but retreating Collier Glacier, which contains 700 million cubic feet (20×106 m3) of ice and is the thickest and largest glacier in the region,[13] descends along the north side of Middle Sister, cutting into the west side of North Sister.[55] Erosion from Pleistocene and Holocene glaciation exposed a plug near the center of Middle Sister.[54]

South Sister

South Sister, also known as "Charity", is the tallest volcano of the trio, standing at 10,363 feet (3,159 m).[1] The eruptive products range from basaltic andesite to rhyolite and rhyodacite.[48][56] It is a predominantly rhyolitic stratovolcano overlying an older shield structure.[44][57] Its modern structure is no more than 50,000 years old,[44][58] and it last erupted about 2,000 years ago.[8] Although its first eruptive events from 50,000 to 30,000 years ago were predominantly rhyolitic, between 38,000 and 32,000 years ago the volcano began to alternate between dacitic/rhyodacitic and rhyolitic eruptions. The volcano built a broad andesitic cone, forming a steep summit cone of andesite about 27,000 years ago. South Sister remained dormant for 15,000 years, after which its composition shifted from dacitic to more rhyolitic lava.[52] An eruptive episode about 2,200 years ago, termed the Rock Mesa eruptive cycle, first spread volcanic ash from flank vents from the south and southwest flanks, followed by a thick rhyolite lava flow. Next, the Devils Hill eruptive cycle consisted of explosive ash eruptions followed by viscous rhyolitic lava flows.[52] Unlike the previous eruptive period, it was caused by the intrusion of a dike of new silicic magma that erupted from 20 vents on the southeast side and from a smaller line on the north side.[59] These eruptions generated pyroclastic flows and lava domes from vents on the northern, southern, eastern, and southeastern sides of the volcano.[60] These relatively recent, postglacial eruptions suggest the presence of a silicic magma reservoir under South Sister, one that could perhaps lead to future eruptions.[52][61]

Unlike its sister peaks,[62] South Sister has an uneroded summit crater about 0.25 mi (0.40 km) in diameter that holds a small crater lake known as Teardrop Pool, the highest lake in Oregon. Its cone consists of basaltic andesite along with red scoria and tephra, with exposed black and red inner walls made of scoria.[63] Hodge Crest, a false peak, formed between 28,000 and 24,000 years ago, roughly around the same time as the main cone.[64]

Despite its relatively young age, every part of South Sister other than its peak has undergone significant erosion due to Pleistocene and Holocene glaciation. Between 30,000 and 15,000 years ago, South Sister's southern flanks were covered with ice streams,[65] and a small amount of ice extended below 3,600 feet (1,100 m).[66] On the volcano's northern flank, below the summit peak, erosion from these glaciers exposed a headwall about 1,200 feet (370 m) high. During the Holocene, smaller glaciers formed, alternating between advance and retreat, depositing moraines and till between 7,000 and 9,000 feet (2,100 and 2,700 m) on the mountain.[66] The Lewis and |Clark glaciers have cirques, or glacial valleys, that made the outer walls of the crater rim significantly steeper.[67] The slopes of South Sister contain small glaciers, including the Lost Creek and Prouty glaciers.[13]

Recent history and potential hazards

When the first geological reconnaissance of the Three Sisters region was published in 1925, its author, Edwin T. Hodge, suggested that the Three Sisters and five smaller mountains in the present-day wilderness area were the remains of an enormous collapsed volcano that had been active during the Miocene or early Pliocene epochs. Naming this ancient volcano Mount Multnomah, Hodge theorized that it had collapsed to form a caldera just as Mount Mazama collapsed to form Crater Lake.[68] In the 1940s, Howel Williams completed an analysis of the Three Sisters vicinity and concluded that Multnomah had never existed, instead demonstrating that each volcano in the area possessed its own individual eruptive history.[68][69] Williams' 1944 paper defined the basic outline of the Three Sisters vicinity, though he lacked access to chemical techniques and radiometric dating. Over the past 70 years, scientists have published several reconnaissance maps and petrographic studies of the Three Sisters,[70] including a detailed geological map published in 2012.[12]

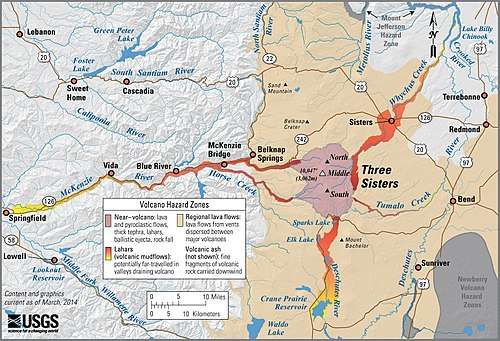

Neither North nor Middle Sister is likely to resume volcanic activity.[62] An eruption from South Sister would pose a threat to nearby life, as the proximal danger zone extends 1.2 to 6.2 miles (2 to 10 km) from the volcano's summits.[71] During an eruption, tephra could accumulate to 1 to 2 inches (25 to 51 mm) in the city of Bend, and mudflows and pyroclastic flows could run down the sides of the mountain, threatening any life in their paths.[48] Eruptions from South Sister could be either explosive or effusive,[72] though an eruption of ash with local volcanic rock accumulation and slow lava flows is considered most likely.[73] The Three Sisters area does not have fumarole activity, although there are hot springs west of South Sister.[12]

From 1986 to 1987, the USGS surveyed the Three Sisters vicinity with tilt-leveling networks and electro-optical distance meters,[74] but South Sister was not the subject of close geodetic analysis for the next two decades.[75] The volcano was found to be potentially active in 2000, when satellite imagery showed a deforming tectonic uplift 3 miles (4.8 km) west of the mountain. The ground began to bulge in late 1997, as magma started to pool about 4 miles (6.4 km) underground.[34][76] Scientists became concerned that the volcano was awakening, but examination of interferograms, or diagrams of patterns formed by wave interference, revealed that only small amounts of deformation occurred.[77] A 2002 study inferred that the composition of intruding magma was basaltic or rhyolitic.[78] A map at the Lava Lands Visitor Center of the Newberry National Volcanic Monument south of Bend shows the extent of the uplift, which reaches a maximum of 11 inches (28 cm). In 2004, an earthquake swarm occurred with an epicenter in the area of uplift; the hundreds of small earthquakes subsided after several days. According to a 2011 study, this swarm may have initiated a significant decrease in the peak uplift rate, which dropped by 80 percent after 2004.[79] By 2007 the uplift had slowed, though the area was still considered potentially active.[80]

A study published in 2010 described the magma intrusion as having a volume of about 2.1 billion cubic feet (59,000,000 m3).[81] Scientists determined in 2013 that the uplift had slowed to a rate of about 0.3 inches (7.6 mm) per year, compared to up to 2 inches (51 mm) per year in the early 2000s.[76] Because of the uplift at South Sister, the USGS planned to increase monitoring of the Three Sisters and their vicinity by installing a global positioning system (GPS) receiver, sampling airborne and ground-based gases, and adding seismometers.[82] The agency completed a GPS survey campaign, including planning, documentation, and data processing and archiving, at South Sister in 2001, as well as annual InSAR radar observations from 1992 to 2001, and it followed up with campaign GPS and tilt-leveling surveys in August 2004.[74] As of 2009, semi-permanent GPS networks have been deployed every year at the Three Sisters,[83] continually showing that inflation persists at South Sister.[75]

Ecology

The ecology of the Three Sisters reflect their location in central Oregon's Cascade Range. The westside slopes from 3,000 to 6,500 feet (910 to 2,000 m) lie in the Western Cascade Montane Highlands ecoregion, where precipitation is abundant. Forests here consist predominantly of Douglas-fir and western hemlock, with minor components of mountain hemlock, noble fir, subalpine fir, grand fir, Pacific silver fir, red alder, and Pacific yew. Vine maples, rhododendron, Oregon grape, huckleberry, and thimbleberry grow beneath the trees.[84][85] Douglas-fir is dominant below 3,500 feet (1,100 m), while western hemlock dominates above.[86]

Timberline at the Three Sisters occurs at 6,500 feet (2,000 m),[87] where the forest canopy opens and the subalpine zone begins. These forests lie in the Cascade Crest montane forest ecoregion.[84][85] Mountain hemlock trees dominate the forest in this area,[88] while meadows sustain sedges, dwarf willows, tufted hairgrass,[84][85] lupine, red paintbrush, and Newberry knotweed.[88]

Tree line occurs at 7,500 feet (2,300 m).[87] The vegetation in this harsh alpine zone consists of herbaceous and shrubby subalpine meadows. This zone has a large winter snowpack, with low temperatures for much of the year. There are patches of mountain hemlock, subalpine fir, and whitebark pine near the treeline, as well as wet meadows supporting Brewer's sedge, Holm's sedge, black alpine sedge, tufted hairgrass, and alpine aster. Near the peaks of the Three Sisters, there are extensive areas of bare rock.[84][85]

The lower eastern slopes of the Three Sisters below 5,200 feet (1,600 m) lie in the Ponderosa Pine/Bitterbrush Woodland ecoregion. This ecoregion has less precipitation than the western slopes and has soil derived from Mazama Ash (ash erupted from Mount Mazama).[84][85] Stream flow changes little throughout the year due to the region's volcanic hydrogeology. These slopes support nearly pure stands of ponderosa pine. Understory vegetation includes greenleaf manzanita and snowberry at higher elevations and antelope bitterbrush at lower elevations. Mountain alder, stream dogwood, willows, and sedges grow along streams.[84][85]

Local fauna includes birds such as blue and ruffed grouse, small mammals like pikas, chipmunks, and golden-mantled ground squirrels,[89] and larger species like the Columbian black-tailed deer, mule deer, Roosevelt elk, and American black bear. Bobcats, cougars, coyotes, wolverines, martens, badgers, weasels, bald eagles, and several hawk species are many of the predators throughout the Three Sisters area.[90]

Human history

The Three Sisters area was occupied by Amerindians since the end of the last glaciation, mainly the Northern Paiute to the east and Molala to the west. They harvested berries, made baskets, hunted, and made obsidian arrowheads and spears. Traces of rock art can be seen at Devils Hill, south of South Sister.[91]

The first Westerner to discover the Three Sisters was the explorer Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson Bay Company in 1825. He describes "a number of high mountains" south of Mount Hood.[92] Ten months later in 1826, the botanist David Douglas reported snow-covered peaks visible from the Willamette Valley.[92] As the Willamette Valley was gradually colonized in the 1840s, Euro-Americans approached the summits from the west and probably named them individually at that time.[92] Explorers, such as Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth in 1839 and John Frémont in 1843, used the Three Sisters as a landmark from the east.[92] The area was further explored by John Strong Newberry in 1855 as part of the Pacific Railroad Surveys.[92]

In 1862, to connect the Willamette Valley to the ranches of Central Oregon and the gold mines of eastern Oregon and Idaho, Felix and Marion Scott traced a route over Scott Pass. This route was known as the Scott Trail, but was superseded in the early 20th century by the McKenzie Pass Road further north.[92] Around 1866, there were reports that one of the Three Sisters emitted some fire and smoke.[93]

In the late 19th century, there was extensive wool production in eastern Oregon. Shepherds led their herds of 1,500 to 2,500 sheep to the Three Sisters. They arrived in eastern foothills near Whychus Creek by May or June, and then climbed to higher pastures in August and September. By the 1890s, the area was getting overgrazed.[94] Despite regulatory measures, sheep grazing peaked in 1910 before being banned in the 1930s at North and Middle Sister, and in 1940 at South Sister.[95]

In 1892, President Grover Cleveland decided to create the Cascades Forest Reserve, based on the authority of the Forest Reserve Act of 1891.[96] Cascades Reserve was a strip of land from 20 to 60 miles (30 to 100 km) wide around the main crest of the Cascade Range, stretching from the Columbia River almost to the border with California.[97] In 1905, administration of the Reserve was moved from the General Land Office to the United States Forest Service.[98] The Reserve was renamed the Cascade National Forest in 1907. In 1908, the forest was split: the eastern half became the Deschutes National Forest, while the western half merged in 1934 to form the Willamette National Forest.[99]

Most of the Three Sisters glaciers were described for the first time by Ira A. Williams in 1916.[100] Collier Glacier, between North and Middle Sister, was first studied and mapped by Edwin Hodge.[20] Ruth Hopsen Keen took a forty-year photographic record of Collier Glacier, documenting part of the 0.93-mile (1,500 m) retreat of the glacier from 1910 to 1994.[20]

In the 1930s, the Three Sisters were part of a proposed National Monument.[101] To maintain its authority over the region, the Forest Service decided to create a 191,108-acre (773 km2) primitive area in 1937.[101] The following year, at the instigation of Forest Service employee Bob Marshall, it was expanded by 55,620 acres (225 km2) in the French Pete Creek basin.[101] In 1957, the Forest Service decided to reclassify the area as a wilderness area and removed the old-growth forest of the French Pete Creek basin, despite protests of local environmental activists.[101] The area became part of the National Wilderness Preservation System when the Wilderness Act of 1964 was passed, but the area still excluded the French Pete Creek basin.[101] Responding to environmental mobilization throughout the state of Oregon, Congress passed the Endangered American Wilderness Act of 1978, which led to the reinstatement of French Pete Creek and its surroundings in the Three Sisters Wilderness Area.[101] The Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 further expanded the wilderness with the addition of 38,100 acres (154 km2) around Erma Bell Lakes.[101]

Recreation

The Three Sisters are a popular climbing destination for hikers and mountaineers.

Due to extensive erosion and rockfall, North Sister is the most dangerous climb of the three peaks,[102] and is often informally called the "Beast of the Cascades".[103] One of its peaks, Little Brother, can be safely scrambled.[104] The first recorded ascent of North Sister was made in 1857 by six people, including Oregon politicians George Lemuel Woods and James McBride, according to a story published in Overland Monthly in 1870.[105][106] Today, the common trail covers 11 miles (18 km) round-trip, gaining 3,165 feet (965 m) in elevation.[104]

Middle Sister can also be scrambled, for a round-trip of 16.4 miles (26.4 km) and an elevation gain of 4,757 feet (1,450 m).[107]

South Sister is the easiest of the three to climb, and has a trail all the way to summit.[108] The standard route up the south ridge runs for 12.6 miles (20.3 km) round-trip, rising from 5,446 feet (1,660 m) at the trailhead to 10,363 feet (3,159 m) at its summit.[109] It is a popular climb during August and September, with up to 400 people each day.[108]

Notes

- "South Sister". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- "North Sister Quadrangle". USGS. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- The NGVD 29 elevation of 3,062.3 meters was converted using VERTCON to the NAVD 88 elevation of 3,063.7 meters.

- "North Sister Quadrangle". USGS. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- The NGVD 29 elevation of 3,073.9 meters was converted using VERTCON to the NAVD 88 elevation of 3,075.3 meters.

- Martin, Andy. "OREGON P2000s". Peaklist. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- "South Sister". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- "Three Sisters". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Bishop & Allen 2004, pp. 139–142.

- Richard, Terry (2010-08-28). "Three Sisters loop offers one of Oregon's most scenic backpack trips". OregonLive.com. Advance Internet. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- "The Oregon Top 100". SummitPost. June 8, 2013. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, p. 1.

- Harris 2005, p. 57.

- "Geology and History Summary for Three Sisters". U.S. Geological Survey, Cascades Volcano Observatory. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- McArthur 1974, p. 544.

- "Three Sisters Wilderness: General". Wilderness Connect. U.S. Forest Service and the University of Montana. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- Joslin 2005, p. 34.

- Joslin 2005, pp. 32–33.

- Fountain, Andrew G. "Glaciers of Oregon" (PDF). The Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved 2018-05-28.

- "Glaciers in Oregon". Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- Wuerthner 2003, p. 174.

- Joslin 2005, p. 44.

- Joslin 2005, p. 47.

- "Central Oregon Fire Environment". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- Richard, Terry (2015-08-30). "Hiking Pole Creek fire three years after burn in Three Sisters Wilderness". OregonLive.com. Advance Publications. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Urness, Zach (2017-08-15). "11 new wildfires prompt closure of 266,891 acres in Three Sisters Wilderness". Statesman Journal. Gannett Company. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- Darling, Dylan (2017-08-16). "Lightning-sparked wildfires prompt large closure of Three Sisters Wilderness east of Eugene". The Register-Guard. Guard Publishing Co. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- "Fire forces trail closures in Three Sisters Wilderness". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- "Prescribed Fire in Central Oregon". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- Joslin 2005, p. 30.

- Joslin 2005, p. 31.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, pp. 11–12.

- Joslin 2005, pp. 30–31.

- Harris 2005, p. 179.

- Riddick & Schmidt 2011, p. 1.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, p. 9.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, p. 10.

- Plummer & McGeary 1988, pp. 51 and 57.

- Conrey, RM; Donnelly-Nolan, J; Taylor, EM; Champion, D; Bullen, T (2001). "The Shevlin Park Tuff, Central Oregon Cascades Range: Magmatic processes recorded in an arc-related ash-flow tuff". Transactions of the American Geophysical Union. 82 (47): V32D–0994. Bibcode:2001AGUFM.V32D0994C. Fall Meeting Supplement, Abstract V32D-0994.

- Harris 2005, p. 33.

- Plummer & McGeary 1988, p. 54.

- Faculty of the School of Geography 2006.

- Hildreth 2007, p. 27.

- Hildreth 2007, p. 28.

- Wood & Kienle 1992, p. 184.

- "Eruption History for North Sister". U.S. Geological Survey. 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- Harris 2005, p. 183.

- Sherrod et al. 2004, p. 11.

- Joslin 2005, p. 35.

- Harris 2005, pp. 182–84.

- "Oregon Volcanoes – Middle Sister Volcano". U.S. Forest Service. 2004-03-25. Archived from the original on 2011-05-16.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, p. 11.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, p. 12.

- Wood & Kienle 1992, p. 185.

- Harris 2005, pp. 186–87.

- "Oregon Volcanoes – South Sister Volcano". U.S. Forest Service. 2004-03-25. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12.

- Williams 1944, p. 49.

- Harris 2005, p. 189.

- Harris 2005, p. 190.

- Dzurisin et al 2009, p. 1091.

- Hildreth 2007, p. 30.

- Joslin 2005, p. 37.

- Harris 2005, pp. 187–88.

- Harris 2005, p. 188.

- Harris 2005, p. 191.

- Harris 2005, p. 192.

- Harris 2005, p. 193.

- Harris 2005, p. 182.

- Williams 1944.

- Fierstein, Hildreth & Calvert 2011, pp. 147–48.

- Scott et al. 2000, p. 8.

- Wicks Jr et al 2002, p. 4.

- Hildreth, Fierstein & Calvert 2012, p. 15.

- Dzurisin et al 2006, p. 38.

- Poland et al. 2017, p. 11.

- "Bulge near South Sister volcano has nearly stopped growing". The Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon. Associated Press. 2013-02-05. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- Wicks Jr et al 2002, p. 1.

- Wicks Jr et al 2002, p. 3.

- Riddick & Schmidt 2011, p. 11.

- "Modern Deformation and Uplift in the Sisters Region". U.S. Geological Survey. 2013-11-18. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- Riddick & Schmidt 2011, p. 8.

- "Three Sisters: Index of Monthly Reports". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. 2013. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- Poland et al. 2017, p. 4.

- Thorson et al. 2003.

- Pater et al. 1998.

- Joslin 2005, p. 60.

- Van Vechten 1960, p. 1.

- Joslin 2005, p. 48.

- Joslin 2005, p. 49.

- Joslin 2005, pp. 49–50.

- Joslin 2005, p. 61.

- Joslin 2005, p. 62.

- "Eruption (Three Sisters)". Volcanoes USGS Gov. Seattle Weekly Gazette. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Joslin 2005, pp. 65–66.

- Joslin 2005, p. 67.

- Langille 1903, p. 15.

- Langille 1903, p. 18.

- "Our History". US Forest Service. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- Davis 1983, pp. 743–788.

- Williams, IA (1916). "Glaciers of the Three Sisters [Oregon]". Mazama. 5 (1): 14–23.

- Wuerthner 2003, p. 175.

- Smoot 1993, p. 137.

- Harris 2005, p. 185.

- Bond 2005, pp. 59–61.

- "Story of First Ascent of North Sister is Related". The Register-Guard. Guard Publishing Co. 1942-01-04. p. 9. Retrieved 2015-04-26.

- Victor, Mrs. F. F. (March 1870). "Trail-Making in the Oregon Mountains". Overland Monthly. 4 (3): 201–213. Retrieved 2015-04-26.

- Bond 2005, pp. 61–64.

- Umess, Zach (3 September 2014). "Oregon's beginner-friendly mountain a grueling adventure". Statesman Journal. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- Bishop & Allen 2004, p. 139.

References

- Bishop, E. M.; Allen, J. E. (2004). Hiking Oregon's Geology. Seattle, Washington: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-847-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bond, B. I. (2005). 75 Scrambles in Oregon: Best Non-Technical Ascents. Seattle, Washington: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-550-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Richard C., ed. (1983). Encyclopedia of American Forest and Conservation History (PDF). II. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 743–788. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dzurisin, D.; Lisowski, M.; Wicks, Jr., C. W (2009). "Continuing inflation at Three Sisters volcanic center, central Oregon Cascade Range, USA, from GPS, leveling, and InSAR observations". Bulletin of Volcanology. 71 (10): 1091–1110. Bibcode:2009BVol...71.1091D. doi:10.1007/s00445-009-0296-4.

- Dzurisin, D.; Lisowski, M.; Wicks, Jr., C. W; Poland, M. P.; Endo, E. T. (2006). "Geodetic observations and modeling of magmatic inflation at the Three Sisters volcanic center, central Oregon Cascade Range, USA". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 150 (1–3): 35–54. Bibcode:2006JVGR..150...35D. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.07.011.

- Faculty of the School of Geography, Geology and Environmental Science (2006). "Rhyolite". The University of Auckland. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- Fierstein, J.; Hildreth, W.; Calvert, A. T. (2011). "Eruptive history of South Sister, Oregon Cascades". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 207 (3–4): 145–179. Bibcode:2011JVGR..207..145F. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.06.003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, S. L. (2005). "Chapter 13: The Three Sisters". Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes (Third ed.). Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-511-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hildreth, W. (2007). Quaternary Magmatism in the Cascades, Geologic Perspectives. United States Geological Survey. Professional Paper 1744. Retrieved 2017-11-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hildreth, W.; Fierstein, J.; Calvert, A. T. (2012). Geologic map of Three Sisters volcanic cluster, Cascade Range, Oregon: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3186, pamphlet. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-11-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joslin, L. (2005). The Wilderness Concept and the Three Sisters Wilderness: Deschutes and Willamette National Forests, Oregon. Bend, Oregon: Wilderness Associates. ISBN 978-0-9647167-4-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langille, Harold Douglas (1903). Forest Conditions in the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, Oregon. 9–10. U.S. Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McArthur, L. A. (1974). Oregon Geographic Names (Fourth ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87595-102-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pater, D. E.; Bryce, S. A.; Thorson, T. D.; Kagan, J.; Chappell, C.; Omernik, J. M.; Azevedo, S. H.; Woods, A. J. (1998). Ecoregions of Western Washington and Oregon (PDF) (Map). U.S. Geological Survey. (Link to back of map).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plummer, Charles C.; McGeary, David (1988). Physical Geology (4th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-697-05092-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poland, M. P.; Lisowski, M.; Dzurisin, D.; Kramer, R.; McLay, M.; Pauk, B. (2017). "Volcano geodesy in the Cascade arc, USA". Bulletin of Volcanology. 79 (59): 1–33. Bibcode:2017BVol...79...59P. doi:10.1007/s00445-017-1140-x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riddick, S. N.; Schmidt, D. A. (2011). "Time-dependent changes in volcanic inflation rate near Three Sisters, Oregon, revealed by InSAR". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 12 (12): n/a. Bibcode:2011GGG....1212005R. doi:10.1029/2011GC003826.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, W. E.; Iverson, R.M.; Schilling, S.P.; Fisher, B.J. (2000). "Volcano Hazards in the Three Sisters Region, Oregon". Open-File Report 99-437. Retrieved 2008-05-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherrod, D. R.; Taylor, E. M.; Ferns, M. L.; Scott, W. E.; Conrey, R. M.; Smith, G. A. (2004). "Geologic Map of the Bend 30-×60-Minute Quadrangle, Central Oregon" (PDF). Geologic Investigations Series I–2683. Retrieved 2017-11-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smoot, J. (1993). Climbing the Cascade Volcanoes. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1-56044-889-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thorson, T. D.; Bryce, S. A.; Lammers, D. A.; Woods, A. J.; Omernik, J. M.; Kagan, J.; Pater, D. E.; Comstock, J. A. (2003). Ecoregions of Oregon (PDF) (Map). U.S. Geological Survey. (Link to back of map).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Vechten, GW (1960). The ecology of the timberline and alpine vegetation of the Three Sisters (PDF) (Thesis). Oregon State College. Retrieved 2017-11-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wicks, Jr., C. W.; Dzurisin, D.; Ingebritsen, S.; Thatcher, W.; Lu, Zhong; Iverson, J. (2002). "Magmatic activity beneath the quiescent Three Sisters volcanic center, central Oregon Cascade Range, USA". Geophysical Research Letters. 29 (7): 26:1–26:4. Bibcode:2002GeoRL..29.1122W. doi:10.1029/2001GL014205.

- Williams, Howel (1944). Louderback, G. D.; Anderson, C. A.; Camp, C. L.; Chaney, R. W. (eds.). "Volcanoes of the Three Sisters Region, Oregon Cascades" (PDF). Bulletin of the Department of Geological Sciences. 27 (3): 37–84. Retrieved 2017-11-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wood, C. A.; Kienle, J., eds. (1992). Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43811-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wuerthner, George (2003). Oregon's Wilderness Areas: The Complete Guide. Big Earth Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links