Cabrillo National Monument

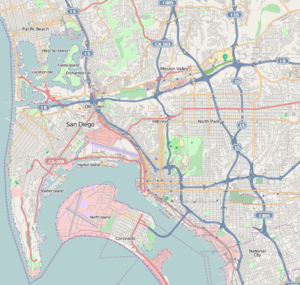

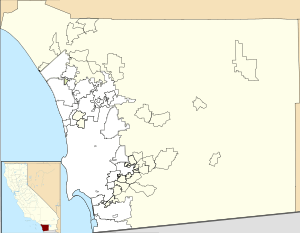

Cabrillo National Monument is at the southern tip of the Point Loma Peninsula in San Diego, California, United States. It commemorates the landing of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo at San Diego Bay on September 28, 1542. This event marked the first time a European expedition had set foot on what later became the West Coast of the United States. The site was designated as California Historical Landmark #56 in 1932.[1] As with all historical units of the National Park Service, Cabrillo was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[3]

Cabrillo National Monument | |

| |

| |

| Nearest city | San Diego |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°40′23″N 117°14′19″W |

| Area | 143.9 acres (58.2 ha) |

| Built | 1949 |

| Architect | US Lighthouse Board; National Park Service |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals |

| Visitation | 842,104 (2018)[2] |

| Website | Cabrillo National Monument |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000224 |

| CHISL No. | 56[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[3] |

| Designated NMON | October 14, 1913[4] |

| Designated CHISL | 1932 |

The annual Cabrillo Festival Open House is held on a Sunday each October. It commemorates Cabrillo with a reenactment of his landing at Ballast Point, in San Diego Bay. Other events are held above at the National Monument and include Kumeyaay, Portuguese, and Mexican singing and dancing, booths with period and regional food, a historical reenactment of a 16th-century encampment, and children's activities.

The park offers a view of San Diego's harbor and skyline, as well as Coronado and Naval Air Station North Island. On clear days, a wide expanse of the Pacific Ocean, Tijuana, and Mexico's Coronado Islands are also visible. A visitor center screens a film about Cabrillo's voyage and has exhibits about the expedition.

The Old Point Loma Lighthouse is the highest point in the park and has been a San Diego icon since 1855. The lighthouse was closed in 1891, and a new one opened at a lower elevation, because fog and low clouds often obscured the light at its location 129 meters (422 feet) above sea level. The old lighthouse is now a museum, and visitors may enter it and view some of the living areas.

The area encompassed by the national monument includes various former military installations, such as coastal artillery batteries, built to protect the harbor of San Diego from enemy warships. Many of these installations can be seen while walking around the area. A former army building hosts an exhibit that tells the story of military history at Point Loma.

The area near the national monument entrance was used for gliding activities in 1929-1935. Several soaring endurance records were established here by William Hawley Bowlus and others including the first 1-hour flight in a sailplane, and a 15-hour flight in 1930 which surpassed the world record for soaring endurance. Even Charles Lindbergh soared in a Bowlus sailplane along the cliffs of Point Loma in 1930. Markers for these accomplishments can be found near the entrance, and the site is recognized as a National Soaring Landmark by the National Soaring Museum.[5]

History

On October 14, 1913, by presidential proclamation, Woodrow Wilson reserved 0.5 acres (2,000 m2) of Fort Rosecrans for "The Order of Panama ... to construct a heroic statue of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo."[4] By 1926 no statue had been placed and the Order of Panama was defunct, so Calvin Coolidge authorized the Native Sons of the Golden West to erect a suitable monument,[4] but they were also unable to carry out the commission.

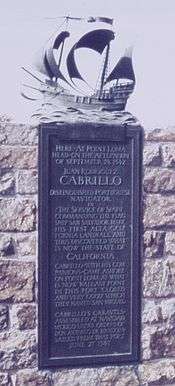

A major renovation of the half-acre monument was undertaken in 1935; the deteriorating lighthouse was refurbished, a new road to the monument was built, and the Portuguese ambassador to the United States presented a bronze plaque, honoring Cabrillo as a "distinguished Portuguese navigator in the service of Spain" who made "the first Alta California landfall".[6]

In 1939 the Portuguese government commissioned a heroic statue of Cabrillo and donated it to the United States. The sandstone statue, executed by sculptor Alvaro de Bree, is 14 feet (4.3 m) tall and weighs 14,000 pounds (6,400 kg). The statue was intended for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco but arrived too late and was stored in an Oakland, California garage. Then-State Senator Ed Fletcher managed to obtain the statue in 1940 over the objections of Bay Area officials and shipped it to San Diego. It was stored for several years on the grounds of the Naval Training Center San Diego, out of public view, and was finally installed at Cabrillo Monument in 1949. The sandstone statue suffered severe weathering because of its exposed position and was replaced in 1988 by a replica made of limestone.[7]

Cabrillo Monument was off-limits to the public during World War II because the entire south end of the Point Loma Peninsula was reserved for military purposes. Following the war the area of the national monument was enlarged significantly by Presidents Eisenhower and Ford.[8] It currently includes more than 140 acres (57 ha).

Flora and fauna

Despite factors such as the toxicity of the San Diego Harbor, over-harvesting of native species, large-scale developments for the 3.1 million residents of the San Diego-Carlsbad Metropolitan Area, and the introduction of exotic and harmful species to the area, there is still a vast array of flora and fauna that inhabit the Monument area.[9]

One of the most thriving and diverse animal communities of Cabrillo National Monument is located in the intertidal zone and tide pools. The species that live in the tide pools include coralline algae, chitons, true limpets, acorn barnacles (Sessilia), goose neck barnacles, rock louse, sea lettuce, kelp fly (Coelopa frigida or seaweed fly), pink thatched barnacles, encrusting algae, periwinkles, mussels (Mytilus californianus), dead man's fingers (Codium fragile), sea bubbles, unicorn snail (Acanthina spirata), anemones, Tegula top snails, sculpin, aggregating anemone, sandcastle worms, hermit crabs, rockweed (Silvetia fastigiata), wavy turban snails (Turbo fluctuosus), keyhole limpet (Fissurellidae), brittle star, surfgrass, surfgrass limpet, kelp crab, garibaldi, sea hare, opaleye, bat star, knobby blue star, sea urchin, sargassum weed, feather boa kelp, octopus, chestnut cowry, sea palm, ruddy turnstone, and lined shore crab.[10] The Monument advises that the best time to see the tide pools is in the late fall or winter, when tides are rated at negative one or lower during daylight hours.[11]

In the winter (December through March), migrating gray whales can be seen off the coast from the Whale Overlook station, 100 yards south of the old lighthouse. Established in 1950, this was the first public whale watching lookout point in the world. During its first year of operation, 10,000 people visited the lookout to observe the gray whale migration.[12]

Native coastal sage scrub habitat along the Bayside Trail offers a place to hike or relax, as well as a noteworthy habitat for wildlife.

The park's activities are supported by the Cabrillo National Monument Foundation,[13] a private nonprofit organization which helps with educational activities and special projects as well as operating a bookstore at the site. The foundation has also published several books on historic and scientific topics related to the Monument.

Native and non-native species

The park's ecosystems have encountered multiple non-native species not originally part of the habitat but rather have been introduced and adapted to it over time. One example of non-native species harming native species is the Argentine ant. These ants have displaced the native ants, and this impacted the coast horned lizard population, which only ate the native ants. In those areas where Argentine ants had established colonies, the coast horned lizard is no longer found.[14]

Climate

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Point Loma lighthouses

Old Point Loma Lighthouse

In 1851, a year after California entered the Union, the U.S. Coastal Survey selected the heights of Point Loma to be a navigational aid. The crest seemed like the right location: it stood 422 feet above sea level, overlooking the bay and the ocean, and a lighthouse there could serve as both a harbor light and a coastal beacon.

Construction began on the lighthouse in early 1854 and was completed in November 1855. By late summer 1854, the work was done. More than a year passed before the lighting apparatus - a five-foot-tall 3rd order Fresnel lens, the best available technology - arrived from France and was installed. At dusk on November 15, 1855, the keeper climbed the winding stairs and lit the oil lamp for the first time. In clear weather its light was visible at sea for 25 miles. For the next 36 years, except on foggy nights, it welcomed sailors to San Diego harbor. However, the lighthouse's location on top of a 400-foot cliff meant that fog and low clouds often obscured the light from the view of ships.

On March 23, 1891, the flame was permanently extinguished and the light was replaced by the New Point Loma lighthouse at a lower elevation. In 1984, the light was lit by the National Park Service for the first time in 93 years to celebrate the site's 130th birthday. [16]

New Point Loma Lighthouse

After boarding up the old lighthouse in 1891, the keeper moved his family and belongings into a new light station at the bottom of the hill, which is still an active light. It can be seen from the Whale Overlook, 100 yards south of the Old Point Loma Lighthouse, or from the tide pool area.

Visitor Center

The Visitor Center offers a place to purchase souvenirs and learn about the park's history. The center also allows visitors the chance to communicate with Park Rangers and volunteers. Visitors can learn the day's weather readings, the time of low tide, get a National Park Passport stamped, visit the “Age of Exploration” exhibit, and learn the times for ranger talks/guided tours and auditorium showings. The auditorium offers several showings a day, and features three different films including: “In Search of Cabrillo,” “On the Edge of Land and Sea,” and “First Breath: Gray Whales.” Cabrillo National Monument also hosts a "Junior Ranger" program in which children can earn a Junior Ranger badge by exploring the park and filling out an activity sheet. In 2013, Junior Ranger Day was held on April 27.[17]

Events

There are many events throughout the year. Every year there are a few “Fee Free Weekends” where the park entrance fee is waived for all guests. Other annual events include “Whale Watch Weekend,” “Founder’s Day,” and “Open Tower Day.” “Whale Watch Weekend” occurs in January and features exhibitors and special ranger-led walks and talks as guests look for whales during the annual Pacific Gray Whales migration. “Founder’s Day,” August 25, celebrates the establishment of the National Park Service at Cabrillo National Monument; “Open Tower Day,” November 15, marks the anniversary of the Old Point Loma Lighthouse. The tower at the top of the lighthouse, normally closed to visitors, is open to the public on those two days.[18] The park also has one of the fully restored World War II bunkers open to the public on the fourth Saturday of each month.

A four-day commemoration of the park's centennial year had been planned for October 11–14, 2013, but it was cancelled due to the partial shutdown of United States government functions.[6] The park rescheduled the centennial event to coincide with the annual "Fort Rosecrans Goes to War," a tribute to San Diego and World War II, on December 7–8, 2013.[19] Some of the other planned centennial events took place in 2014.[6]

Gallery

- Cabrillo National Monument

Front side, old Point Loma Lighthouse, August 1962

Front side, old Point Loma Lighthouse, August 1962 3-Quarter view, Old Point Loma Lighthouse, February, 2018

3-Quarter view, Old Point Loma Lighthouse, February, 2018 Rear view, Old Point Loma Lighthouse

Rear view, Old Point Loma Lighthouse A crab found in the CNM tidepools, February 2013

A crab found in the CNM tidepools, February 2013 Silver Strand from the Old Point Loma Lighthouse, February 2013

Silver Strand from the Old Point Loma Lighthouse, February 2013- Dry conditions at Cabrillo National Monument, December 2013

Panosphere at Cabrillo National Monument

Panosphere at Cabrillo National Monument

See also

- Hispanic Heritage Sites

- Parks in San Diego

References

- "Cabrillo Landing Site". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Thomas Alan Sullivan. "Proclamations and Orders Relating to the National Park Service: Up to January 1, 1945" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-13. Pages 130-132.

- "Point Loma, San Diego, California - National Soaring Museum". www.soaringmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2015-12-19.

- Rowe, Peter (October 13, 2013). "Cabrillo National Monument at 100". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- Crawford, Richard (August 3, 2008). "Cabrillo statue's journey to San Diego marked by legal twists". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- National Park Service (September 28, 1974). "Proclamation 4319 - Cabrillo National Monument, California". Presidential Proclamations. University of California Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- Understand the Life of Point Loma

- Tegner, Mia (2004). Understanding the Life of Point Loma. San Diego, CA: Cabrillo National Monument Foundation. pp. 56, 62–63.

- Low tide best dates and times Archived 2013-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, Cabrillo National Monument

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2013-08-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cabrillo National Monument Foundation". Cabrillo National Monument Foundation. Archived from the original on 2005-08-18.

- "Environmental Factors: An "Island" in the Big City". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-03-25. Retrieved 2012-12-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cabrillo National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-04-13.

- "Special Events - Cabrillo National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- "Cabrillo National Monument Re-scheduled Centennial Celebration! December 7-8, 2013". Schedule of Events. Cabrillo National Monument. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cabrillo National Monument. |

- Cabrillo National Monument - Official National Park Service website

- Cabrillo National Monument Map

- Cabrillo National Monument Foundation

- The Origin and Development of Cabrillo National Monument 1981 NPS administrative history

- Early History of the California Coast, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary