Mandaeans

Mandaeans (Arabic: ٱلصَّابِئَة ٱلْمَنْدَائِيُّون, romanized: aṣ-Ṣābiʾah al-Mandāʾiyūn) are an ethnoreligious group native to the alluvial plain of southern Mesopotamia and are followers of Mandaeism, a monotheistic Gnostic religion. They were probably the first to practice baptism and are the last surviving Gnostics from antiquity.[18] The Mandaeans were originally native speakers of Mandaic, a Semitic language that evolved from Eastern Middle Aramaic, before many switched to colloquial Iraqi Arabic and Modern Persian. Mandaic is mainly preserved as a liturgical language. In the aftermath of the Iraq War of 2003, the Mandaean community of Iraq, which used to number 60,000–70,000 persons, collapsed; most of the community relocated to nearby Iran, Syria and Jordan, or formed diaspora communities beyond the Middle East. The other community of Iranian Mandaeans has also been dwindling as a result of religious persecution over that decade.[4]

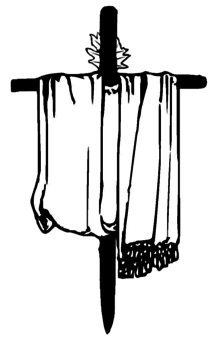

Mandeans in prayer | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 60,000[1] - 70,000[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3,000[3] | |

| 5,000 to 10,000 (2009)[4] | |

| 1,400 [5] | |

| 1,250 families[6] | |

| 8,500[7] | |

| 3,500 to 10,000[8][9][10] | |

| 4,000[11] | |

| 1,000[12] | |

| 1,500[9] | |

| 2,200[13] | |

| 650[14] | |

| 23[15] | |

| 2,500[16]-3,200[17] | |

| Religions | |

| Mandaeism | |

| Scriptures | |

| Ginza Rba, Qolusta, Mandaean Book of John, Haran Gawaita | |

| Languages | |

| Mandaic as liturgical language Neo-Mandaic, Arabic and Persian | |

History

Origin

There are several indications of the ultimate origin of the Mandaeans. Early religious concepts and terminologies recur in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Yardena (Jordan) has been the name of every baptismal water in Mandaeism.[19] The Mandaic language is a dialect of southeastern Mesopotamian Aramaic with significant Akkadian influences and is closely related to the language of the Babylonian Talmud, as well as Syriac. They formally refer to themselves as Nasurai (Nasoraeans). A priest holds the title of Rabbi[20] and a place of worship is called a Mashkhanna.[21] According to Mandaean sources such as the Haran Gawaita, the Nasurai inhabited the areas around Jerusalem and the River Jordan in the 1st century CE. There is archaeological evidence that attests to the Mandaean presence in pre-Islamic Iraq.[22][23] Some scholars, including Kurt Rudolph, connect the early Mandaeans with the Jewish sect of the Nasoraeans.[23] The Mandaeans are considered to be part of the indigenous people of Iraq. [24]

It appears that Mani, the founder of Manichaeism, was partly influenced by the Mandaeans.

Early Persian periods

A number of ancient Aramaic inscriptions dating back to the 2nd century CE were uncovered in Elymais. Although the letters appear quite similar to the Mandaean ones, it is doubtful whether the inhabitants of Elymais were Mandaeans.[25] Under Parthian and early Sasanian rule, foreign religions were tolerated. The situation changed by the ascension of Bahram I in 273, who under the influence of the zealous Zoroastrian high priest Kartir persecuted all non-Zoroastrian religions. It is thought that this persecution encouraged the consolidation of Mandaean religious literature.[25] The persecutions instigated by Kartir seems to temporarily erase Mandaeans from recorded history. Traces of their presence can still however be found in the so-called Mandaean magical bowls and lead strips which were produced from the 3rd to the 7th centuries.[26]

Islamic Caliphates

The Mandaeans re-appear at the beginning of the Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia, when their "head of the people" Anush son of Danqa appears before Muslim authorities showing them a copy of the Ginza Rabba, the Mandaean holy book, and proclaiming the chief Mandaean prophet to be John the Baptist, who is also mentioned in the Quran. The connection with the Quranic Sabians provided them acknowledgement as People of the Book, people who followed a legal minority religion within the Muslim Empire. They appear to have flourished during the early Islamic period, as attested by the voluminous expansion of Mandaic literature and canons. Tib near Wasit is particularly noted as an important scribal centre.[26] Yaqut al-Hamawi describes Tib as a town inhabited by Nabatean (i.e. Aramaic speaking) Sabians who consider themselves to be descendants of Seth, son of Adam.[26]

The status of the Mandaeans became an issue for the Abbasid al-Qahir Billah. To avoid further investigation by the authorities, the Mandaeans paid a bribe of 50,000 dinars and were left alone. It appears that the Mandaeans were even exempt from paying the Jizya, otherwise imposed upon non-Muslims.[26]

Late Persian and Ottoman periods

Early contact with Europeans came about in the mid-16th century, when Portuguese missionaries encountered Mandaeans in Southern Iraq and controversially designated them "Christians of St. John". In the next centuries Europeans became more acquainted with the Mandaeans and their religion.[26]

The Mandaeans suffered persecution under the Qajar rule in the 1780s. The dwindling community was threatened with complete annihilation, when a cholera epidemic broke out in Shushtar and half of its inhabitants died. The entire Mandaean priesthood perished and Mandeism was restored due only to the efforts of few learned men such as Yahia Bihram.[27] Another danger threatened the community in 1870, when the local governor of Shushtar massacred the Mandaeans against the will of the Shah.[27] As a result of these events the Mandaeans retired to the more inaccessible Central Marshes of Iraq.

Modern Iraq and Iran

Following the First World War, the Mandaeans were still largely living in rural areas in the lower parts of British protected Iraq and Iran. Owing to the rise of Arab nationalism, Mandaeans were Arabised at an accelerated rate, especially during the 1950s and '60s. The Mandaeans were also forced to abandon their stands on the cutting of hair and forced military service, which are strictly prohibited in Mandaenism.[28]

The 2003 Iraq War brought more troubles to the Mandaeans, as the security situation deteriorated. Many members of the Mandaean community, who were known as goldsmiths, were targeted by criminal gangs for ransoms. The rise of Islamic Extremism forced thousands to flee the country, after they were given the choice of conversion or death.[29] It is estimated that around 90% of Iraqi Mandaeans were either killed or have fled after the American-led invasion.[29]

The Mandaeans of Iran lived chiefly in Ahvaz, Iranian Khuzestan, but have moved as a result of the Iran–Iraq War to other cities such as Tehran, Karaj and Shiraz. The Mandaeans, who were traditionally considered as People of the Book (members of a protected religion under Islamic rule) lost this status after the Islamic Revolution. However, despite this, Iranian Mandaeans still maintain successful businesses and factories in areas such as Ahwaz. In April 1996, the cause of the Mandaeans' religious status in the Islamic Republic was raised. The parliament came to the conclusion that "Sabaeans" were included in the protected status of People of the Book alongside Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians and specified that, from a legal viewpoint, there is no prohibition against Muslims associating with Mandaeans, who are often regarded as being the Sabaeans mentioned explicitly in the Quran. That same year, Ayatollah Sajjadi of Al-Zahra University in Qom posed three questions regarding the Mandaeans' beliefs and seemed satisfied with the answers. These rulings however, did not lead to Mandaeans regaining their more officially recognized status as People of the Book.[30]

Population

Mandaeans in Iraq

Pre-Iraq War, The Iraqi Mandaean community was centered in Baghdad. The Mandeans originate, however, from southern Iraq in cities like Nasiriyah. Many also live across the border in Southwestern Iran in the cities of Ahvaz and Khorramshahr.[31] Mandaean emigration from Iraq began during Saddam Hussein's rule, but accelerated greatly after the American-led invasion and subsequent occupation.[32] Since the invasion Mandaeans, like other Iraqi ethno-religious minorities (such as Arameans, Armenians, Yazidi, Roma and Shabaks), have been subjected to violence, including murders, kidnappings, rapes, evictions, and forced conversions.[32][33] Mandaeans, like many other Iraqis, have also been targeted for kidnapping since many worked as goldsmiths.[32] Mandaeism is pacifistic and forbids its adherents from carrying weapons.[32][34]

Many Iraqi Mandaeans have fled the country in the face of this violence, and the Mandaean community in Iraq faces extinction.[35][36] Out of the over 60,000 Mandaeans in Iraq in the early 1990s, fewer than 5,000 to 10,000 remain there as of 2007. In early 2007, more than 80% of Iraqi Mandaeans were refugees in Syria and Jordan as a result of the Iraq War. .[37] As of 2019, an Al-Monitor study estimated the Iraqi Mandaean population to be 3,000, 400 of which lived in the Erbil Governorate.[3]

Iranian Mandaeans

The number of Iranian Mandaeans is a matter of dispute. In 2009, there were an estimated 5,000 and 10,000 Mandaeans in Iran, according to the Associated Press.[4] Alarabiya has put the number of Iranian Mandaeans as high as 60,000 in 2011.[38]

Until the Iranian Revolution, Mandaeans were mainly concentrated in the Khuzestan province, where the community used to coexist with the local Arab population. They were mainly employed as goldsmiths, passing their skills from generation to generation.[38] After the fall of the shah, its members faced increased religious discrimination, and many sought a new home in Europe and the Americas.

In Iran, the Gozinesh Law (passed in 1985) has the effect of prohibiting Mandaeans from fully participating in civil life. This law and other gozinesh provisions make access to employment, education, and a range of other areas conditional upon a rigorous ideological screening, the principal prerequisite for which is devotion to the tenets of Islam.[39] These laws are regularly applied to discriminate against religious and ethnic groups that are not officially recognized, such as the Mandaeans, Ahl-e Haq, and Baha'i.[40]

In 2002 the US State Department granted Iranian Mandaeans protective refugee status; since then roughly 1,000 have emigrated to the US,[4] now residing in cities such as San Antonio, Texas.[41] On the other hand, the Mandaean community in Iran has increased over the last decade, because of the exodus from Iraq of the main Mandaean community, which used to be 60,000–70,000 strong.

Other countries in the Middle East

Following the Iraq War, the Mandaean community dispersed throughout the Middle East. Living as refugees the Mandaeans in Jordan number 49 families,[6] while in Syria there are as many as 1,250 families.[6]

Diaspora

There are small Mandaean diaspora populations in Sweden (c. 7,000), Australia (6,906 in 2016),[42] the US (c. 2,500), the UK (c. 1,000), and Canada.[35][43][44][45][46][47] Sweden became a popular destination because a Mandaean community existed there before the war and the Swedish government has a liberal asylum policy toward Iraqis. Of the 7000 Mandaeans in Sweden, 1,500 live in Södertälje.[43][48] The scattered nature of the Mandaean diaspora has raised fears among Mandaeans for the religion's survival. Mandaeism does not allow conversion, and the religious status of Mandaeans who marry outside the faith and their children is disputed.[4][33]

The status of the Mandaeans has prompted a number of American intellectuals and civil rights activists to call upon the U.S. government to extend refugee status to the community. In 2007, The New York Times ran an op-ed piece in which Swarthmore professor Nathaniel Deutsch called for the Bush administration to take immediate action to preserve the community.[37] Iraqi Mandaeans were given refugee status by the US State Department in 2007. Since then more than 2500 have entered the US, many settling in Worcester, Massachusetts.[4][49] The community in Worcester is believed to be the largest in the United States and the second largest community outside the Middle East.[50] 2,600 Mandaeans from Iran have been settled in Texas since the Iraq War.[51]

On the 15th of September 2018 the first ever purpose-built Beth Manda in Europe was consecrated in Dalby, Scania, Sweden named Beth Manda Yardna.[52][53]

Religion

Mandaeans are a closed ethno-religious community, practicing Mandaeism, which is a monotheistic Gnostic religion[54]:4[55]:4 (Aramaic manda means "knowledge," as does Greek gnosis) with a strongly dualistic worldview. Its adherents revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enosh, Noah, Shem, Aram and especially John the Baptist.[56][57]

The Mandaeans group existence into two main categories: light and dark. They have a dualistic view of life, that encompasses both good and evil; all good is thought to have come from the World of Light (i.e. lightworld) and all evil from the World of Darkness. In relation to the body–mind dualism coined by Descartes, Mandaeans consider the body, and all material, worldly things, to have come from the Dark, while the soul (sometimes referred to as the mind) is a product of the lightworld. Mandaeans believe the World of Light is ruled by a heavenly being, known by many names, such as “Life,” “Lord of Greatness,” “Great Mind,” or “King of Light”.[58] This being is so great, vast, and incomprehensible that no words can fully depict how awesome Life is. It is believed that an innumerable number of beings, manifested from the light, surround Life and perform cultic acts of worship to praise and honor this great being. They inhabit worlds separate from the lightworld and are commonly referred to as emanations from the First Life; their names include Second, Third, and Fourth Life (i.e. Yōšamin, Abathur, and Ptahil).[58]

The Lord of Darkness (Krun) is the ruler of the World of Darkness formed from dark waters representing chaos.[58][59] A main defender of the darkworld is a giant monster, or dragon, with the name “Ur;” an evil, female ruler also inhabits the darkworld, known as “Ruha”.[58] The Mandaeans believe these malevolent rulers created demonic offspring who consider themselves the owners of the Seven (planets) and Twelve (Zodiac signs).[58]

According to Mandaean beliefs, the world is a mixture of light and dark created by the demiurge (Ptahil) with help from dark powers, such as Ruha, the Seven, and the Twelve.[58] Adam's body (i.e. believed to be the first human created by God in Abrahamic tradition) was fashioned by these dark beings; however, his “soul” (or mind) was a direct creation from the Light. Therefore, many Mandaeans believe the human soul is capable of salvation because it originates from the lightworld. The soul, sometimes referred to as the “inner Adam” or “hidden Adam,” is in dire need of being rescued from the Dark, so it may ascend into the heavenly realm of the lightworld.[58] Baptisms are a central theme in Mandaeanism, believed to be necessary for the redemption of the soul. Mandaeans do not perform a single baptism, as in religions such as Christianity; rather, they view baptisms as a ritualistic act capable of bringing the soul closer to salvation.[60] Therefore, Mandaeans get baptized repeatedly during their lives. John the Baptist is a key figure for the Mandaeans; they consider him to have been a Mandaean. John is referred to as their greatest and final teacher.

Language

See also

References

- Bell, Matthew

- Iraqi minority group needs U.S. attention, Kai Thaler,Yale Daily News, March 9, 2007.

- Salloum, Saad (August 29, 2019). "Iraqi Mandaeans fear extinction". Al-Monitor. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Contrera, Russell. "Saving the people, killing the faith – Holland, MI". The Holland Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "Jordan's Mandaean minority fear returning to post-ISIS Iraq". The National. June 9, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- Who Cares for the MANDAEANS?, Australian Islamist Monitor

- Ekman, Ivar: An exodus to Sweden from Iraq for ethnic Mandaeans

- Hegarty, Siobhan (July 21, 2017). "Meet the Mandaeans: Australian followers of John the Baptist celebrate new year". ABC. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- The Mandaean Associations Union:Mandaean Human Rights Annual Report November 2009

- Hinchey, Rebecca: MANDAENS, a unique culture

- "The Mandaeans · The Worlds of Mandaean Priests". mandaeanpriests.exeter.ac.uk. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Crawford, Angus: Mandaeans – a threatened religion

- Verschiedene Gemeinschaften / neuere religiöse Bewegungen, in: Religionswissenschaftlicher Medien- und Informationsdienst|Religionswissenschaftliche Medien- und Informationsdienst e. V. (Abbreviation: REMID), Retrieved 9 October 2016

- Schou, Kim and Højland, Marie-Louise: Hvem er mandæerne? (Danish), religion.dk

- Society for Threatened Peoples:Leader of the world's Mandaeans asks for help

- MacQuarrie, Brian (August 13, 2016). "Embraced by Worcester, Iraq's persecuted Mandaean refugees now seek 'anchor'—their own temple". The Boston Globe. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- https://www.telegram.com/news/20180401/mandaean-community-opens-office-in-worcester

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvv6I02MNlc

- Rudolph 1977, p. 5.

- McGrath, James F.,"Reading the Story of Miriai on Two Levels: Evidence from Mandaean Anti-Jewish Polemic about the Origins and Setting of Early Mandaeism".ARAM Periodical / (2010): 583–592.

- Secunda, Shai, and Steven Fine. "Shoshannat Yaakov". Brill, 2012. p. 345

- Deutsch 1999, p. 4.

- Rudolph 1977, p. 4.

- Mandaean Association Union,{{cite web|url=https://www.mandaeanunion.org/}

- Buckley 2002, p. 4

- Buckley 2002, p. 5

- Buckley 2002, p. 6

- Mandaean Human Rights Group 2008, p. 5

- Zurutuza, Karlos (29 January 2012). "The Ancient Wither in New Iraq". IPS. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen. "Mandaean Community in Iran". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- "Mandaens iv. Community in Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Ekman, Ivar (April 9, 2007). "An exodus to Sweden from Iraq for ethnic Mandaeans". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Newmarker, Chris (February 10, 2007). "Survival of Ancient Faith Threatened by Fighting in Iraq". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Lupieri 2002, p. 91.

- Iraq's Mandaeans 'face extinction', Angus Crawford, BBC, March 4, 2007.

- Genocide Watch: Mandaeans of Iraq Archived May 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Deutsch, Nathaniel (October 6, 2007). "Save the Gnostics". The New York Times.

- "Iran Mandaeans in exile following persecution". Alarabiya.net. December 6, 2011. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "Ideological Screening (ROOZ :: English)".

- Annual Report for Iran Archived 2011-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, 2005, Amnesty International.

- Updated 33 minutes ago 12/17/2011 8:29:41 AM +00:00 (January 7, 2009). "Ancient sect fights to stay alive in U.S. - US news – Faith – NBC News". NBC News. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Source: ABS (2017), Census of Population and Housing, Reflecting Australia - Stories from the Census, 2016 - Religion, Table 1, ABS Catalogue Number 2071.0.

- "Morgondopp som ger gruppen nytt hopp" (in Swedish).

- Newmarker, Chris (February 10, 2007). "Survival of Ancient Faith Threatened by Fighting in Iraq". The Washington Post and Times-Herald. Associated Press. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- The Plight of Iraq's Mandeans Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, John Bolender. Counterpunch.org, January 8/9, 2005.

- Ekman, Ivar (April 9, 2007). "An exodus to Sweden from Iraq for ethnic Mandaeans". iht.com. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Mandaeans persecuted in Iraq. ABC Radio National (Australia), June 7, 2006.

- Ekman, Ivar (April 9, 2007). "An exodus to Sweden from Iraq for ethnic Mandaeans". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- "These Iraqi immigrants revere John the Baptist, but they're not Christians". Public Radio International. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Moulton, Cyrus. "Mandaean community opens office in Worcester". telegram.com. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Petrishen, Brad. "Worcester branch of Mandaean faith works to plant roots". telegram.com. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Nyheter, SVT (September 15, 2018). "Nu står mandéernas kyrka i Dalby färdig". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- https://lund.lokaltidningen.se/2018-09-18/-Mand%C3%A9ernas-kyrka-invigd-%E2%80%93-f%C3%B6rst-i-Europa-3127706.html

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002), The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people (PDF), Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195153859

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002), The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195153859

- Mandaeism – p. 15 Kurt Rudolph – 1978 This tradition can be explained by an anti-Christian concept, which is also found in Mandaeism, but, according to several scholars, it contains scarcely any traditions of historical events. Because of the strong dualism in Mandaeism ...

- The Light and the Dark: Dualism in ancient Iran, India, and China Petrus Franciscus Maria Fontaine – 1990 "Although it shows Jewish and Christian influences, Mandaeism was hostile to Judaism and Christianity. Mandaeans spoke an East-Aramaic language in which 'manda' means 'knowledge'; this already is sufficient proof of the connection of Mandaeism with the Gnosis...

- Rudolph 2001.

- Drower, Ethel Stefana. The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford At The Clarendon Press, 1937.

- McGrath 2015.

- "Mandaic". Ethnologue. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

Bibliography

- Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People, New York: Oxford University Press 2002.

- Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, The Great Stem of Souls: Reconstruction Mandaean History, Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2005.

- Deutsch, Nathaniel (1999). Guardians of the Gate: Angelic Vice-regency in the Late Antiquity. BRILL. ISBN 9004109099.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ethel Stefana Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran (1937), reprint: Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2002.

- Ethel Stefana Drower, The Secret Adam: A Study of Nasoraean Gnosis, Oxford: Clarendon, 1960.

- Edmondo Lupieri, The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002.

- Rudolph, Kurt (1977). "Mandaeism". In Moore, Albert C. (ed.). Iconography of Religions: An Introduction. 21. Chris Robertson. ISBN 9780800604882.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rudolph, Kurt (June 20, 2001). Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism. A&C Black. pp. 343–366. ISBN 9780567086402.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andrew Phillip Smith, John the Baptist and the Last Gnostics: The Secret History of the Mandaeans, London: Watkins Publishing 2016.

- Edwin M. Yamauchi, Mandaic Incantation Texts (1967), reprint Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2005.

- Edwin M. Yamauchi, Gnostic Ethics and Mandaean Origins (1970), reprint Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2004.

External links

- Mandaean Associations Union

- Resources of the language of the Mandaeans

- Mandaean Scriptures and Fragments

- Mandaean Human Rights Group (2008), Mandaean Human Rights Annual Report (PDF), AINA

- James McGrath on The Mandaeans and Mandaean Gnosticism (2015)