New Square, New York

New Square (Hebrew and Yiddish: שיכון סקווירא) is an all-Hasidic village in the town of Ramapo, Rockland County, New York, United States. It is located north of Hillcrest, east of Viola, south of New Hempstead, and west of New City. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 6,944.[3] In 2018, the population was estimated to be over 8,500.[4] Its inhabitants are predominantly members of the Skverer Hasidic movement who seek to maintain a Hasidic lifestyle disconnected from the secular world.

New Square, New York שיכון סקווירא | |

|---|---|

Village | |

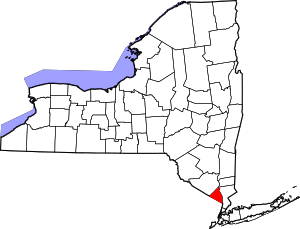

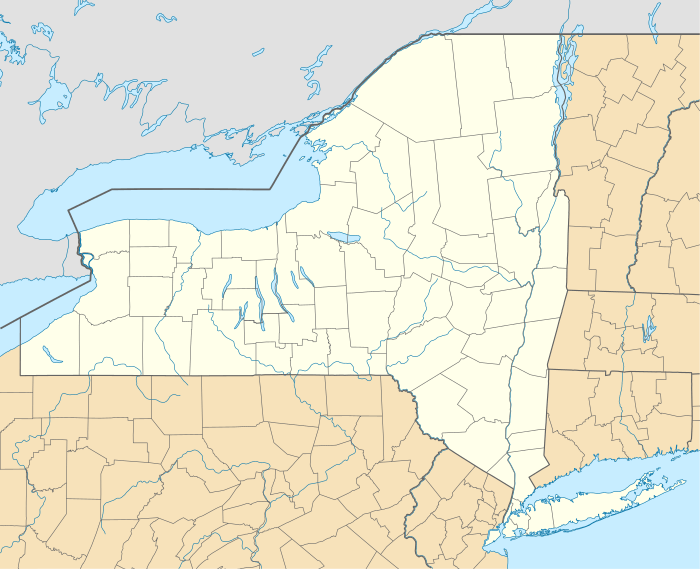

Location in Rockland County and the state of New York. | |

New Square Location within the state of New York and the USA  New Square New Square (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 41°8′23″N 74°1′42″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Rockland |

| Incorporated | November 6, 1961 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Israel Spitzer |

| • Trustees | Yakov Berger, Naftali Biston, Yitzchok Fischer, Abraham Kohl, Fred Schonfeld, and Jacob Unger |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.37 sq mi (0.95 km2) |

| • Land | 0.37 sq mi (0.95 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 492 ft (150 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,944 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 8,763 |

| • Density | 23,877.38/sq mi (9,210.69/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 10977 |

| Area code(s) | 845 |

| FIPS code | 36-50705 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0971939 |

| Website | Official website |

History

New Square is named after the Ukrainian town Skvyra, where the Skverer Hasidim originated. The founders intended to name the settlement New Skvir, but a typist's error anglicized the name.[5] New Square was established in 1954, when the Zemach David Corporation, representing Skverer Grand Rabbi Yakov Yosef Twersky, purchased a 130-acre (0.53 km2) dairy farm near Spring Valley, New York, in the town of Ramapo. At that time, the Skverer community lived in the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn in New York City. Construction began in 1956, and the first four families moved to New Square in December 1956.[6] In 1958, the settlement had 68 houses.[7]

The development of New Square was obstructed by Ramapo's zoning regulations, which forbade the construction of multi-family houses and the use of basements for shops and stores. Multiple families sharing single-family houses said that they belonged to extended families, and businesses in private homes had to be secret. In 1959, the community asked for a building permit to expand its synagogue, located in the basement of a Cape Cod-style house. The Ramapo town attorney requested condemnation of the entire New Square community, claiming that it threatened sewage lines. In response, the community requested incorporation as a village, but Ramapo town officials refused to allow it. In 1961, a New York state court ruled in favor of New Square,[8] and the village was incorporated in July of that year.

After incorporating, New Square set its own zoning and building codes, legalizing the existing houses, and the liens disappeared. Lots were sold, and new houses were built. The basement businesses could trade openly, and new businesses were founded, including a watch assembly plant and a cap manufacturer. Three knitting mills and a used car lot opened, but most men continued to go to work in New York City. A Kollel was opened in 1963. In 1968, Grand Rabbi Yakov Yosef Twersky died; he was succeeded as Grand Rabbi by his son David Twersky.[7]

In New Square's first mayoral election in 1961, Mates Friesel was chosen unopposed. Friesel was re-elected every two years, until his death in 2015, thereby becoming one of the longest-serving mayors in the United States.[9]

Culture

The community in New Square is made up exclusively of Hasidic Jews, mostly from the Skverer Hasidic movement, who wish to maintain a Hasidic lifestyle while keeping outside influences to a minimum. The predominant language spoken in New Square is Yiddish.[10]

People typically marry around 18 to 20 years of age. Girls finish high school at around age 17, and then marry. Custom dictates that women who marry men from other Hasidic communities leave New Square. Some women who left New Square settled in the Borough Park community in Brooklyn and the Monsey community in Ramapo, where the community is not as tightly knit. Men who marry women from outside of the community are encouraged to leave New Square. This is due to a shortage of space; thus, new housing is granted to couples of which both members are from the community.[11]

In 2005, the community's rabbinical court ruled that women should not operate cars.[12] In a 2003 article, Lisa W. Foderaro of The New York Times described New Square as "extremely insular", and said that the community's residents do not own televisions or radios.[13]

Economy

Young women, prior to entering marriage, and before they have children, work as teachers, secretaries, and bookkeepers, or they work in the New Square shopping center as cashiers and clerks. Some of the women, after having children, work as bookkeepers in their homes.[14]

Young men work as teachers, bus drivers, deliverymen, and store clerks. Some work as computer programmers, or as craftsmen and entrepreneurs in the diamond industry. Many study in the kollel, a yeshiva for married men, and receive stipends to support their families.[14]

According to the 2012 census, there are 476 incorporated firms in New Square.

In 1970, the village had the lowest per-capita income in New York State. In 1963, four persons received welfare due to illness. One dozen people received welfare in 1975. In 1992, the village administrator said that in 1975, about two thirds of the families received food stamps and Medicaid.[11]

According to the 2000 census, the median income for a household in the village was $12,162, and the median income for a family was $12,208. Males had a median income of $21,696, versus $29,375 for females. The per capita income for the village was $5,237. About 67.0% of families and 72.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 77.3% of those under age 18 and 14.7% of those age 65 or over.

2007 and 2008 reports from the State of New York stated that 89.8% of the village consisted of low-income and moderate-income residents.[15][16]

As of 2018, New Square is by far the poorest town in New York, with a median annual household income of $21,773, which is nearly $5,000 below that of Kiryas Joel, the next poorest town in the state, and only about a third of the median income across the state as a whole.[17]

Not only is it the poorest town in New York state, but New Square also has the highest poverty and SNAP recipiency rates of any town in the United States. Some 70.0% of New Square residents live in poverty, and 77.1% of area households rely on SNAP benefits to afford food. In comparison, 15.1% of Americans live below the poverty line, and 13.0% of households nationwide receive SNAP benefits.[17]

Geography

New Square is located at 41°8′23″N 74°1′42″W (41.139745, -74.028197).[18]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 0.4 square mile (0.9 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1970 | 1,156 | — | |

| 1980 | 1,750 | 51.4% | |

| 1990 | 2,605 | 48.9% | |

| 2000 | 4,624 | 77.5% | |

| 2010 | 6,944 | 50.2% | |

| Est. 2019 | 8,763 | [2] | 26.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] 2018 estimate[4] | |||

In 1963, the settlement had 85 families and a total of 620 inhabitants. By 1967, this increased to 126 families and 812 total residents. The community celebrated ten marriages in 1967. In 1970, the village had 1,156 inhabitants, with 57% of the population under the age of 18.

The village had around one hundred births each year from 1971 to 1986. By that year, the village had 140 one-, two-, and three-family houses, a 45-unit low-rent apartment complex, 2,100 people, and 450 families, with an average of 7 to 8 children per family. During the late 1970s, the Town of Ramapo denied New Square's attempt to annex land. Six years later, in March 1982, New Square gained the legal right to annex 95 acres (380,000 m2) of land.[11]

New Square's population increased 77.5% between 1990 and 2000. In 2005, the village contained approximately 7,830 residents; 1,350 families, with 5.8 persons per family.[20] Robert Zeliger of Rockland Magazine described New Square in 2007 as "a densely packed haven where Hasidic residents live largely by their own customs and laws".[21] In November 2008, a new water tower serving New Square and the hamlet of Hillcrest opened, increasing residents' water pressure.[22]

As of the census[23] of 2000, there were 4,624 people, 820 households, and 786 families residing in the village. The population density was 12,811.8 people per square mile (4,959.3/km2). There were 838 housing units, at an average density of 2,321.9 per square mile (898.8/km2). The racial make-up of the village was 96.95% White, 1.64% African American, 0.89% Asian, and 0.52% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.41% of the population. 87.26% speak Yiddish at home, 7.68% English, and 4.11% Hebrew.[24]

There were 820 households, out of which 77.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 92.6% were married couples living together, 2.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 4.1% were non-families. 3.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 5.64, and the average family size was 5.81.

In the village, the population was spread out, with 60.5% under the age of 18, 13.9% from 18 to 24, 15.9% from 25 to 44, 7.1% from 45 to 64, and 2.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 14 years. For every 100 females, there were 105.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.7 males. The median income for a household in the village was $21,172, and the median income for a family was $21,758. Males had a median income of $35,871, versus $21,389 for females. The per capita income for the village was $6,585. About 58.0% of families and 58.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 60.9% of those under age 18 and 36.2% of those age 65 or over.

A 2007 report stated that each year, one half of the women between ages 18 and 25 gave birth.[16]

Government and infrastructure

As of 1992, the Village of New Square has a mayor, a mayor's assistant, a board of trustees, a village clerk, and a justice of the peace. The mayor's assistant performs the bulk of administrative work. The justice of the peace mainly handles harassment cases perpetrated by outsiders within New Square.[14]

The Hillcrest Fire Department (also known as the Moleston Fire District) provides fire protection services to New Square. In March 2007, the fire district met with Town of Ramapo supervisors, and proposed removing New Square from its fire district, after a February 7, 2007, fire that destroyed two buildings in New Square. Further hazards stem from the fact that the town has only one main access road (Washington Avenue), and the failure of some residents to yield to emergency vehicles, or to the crowd of people on the streets surrounding an incident. There also have been isolated cases of residents tampering with fire equipment, while responders are on scene.

The fire department felt concern about a lack of fire protection in buildings in New Square. On March 29, 2007, Ramapo town officials met fire district officials and fire department chiefs. On April 4 of that year, the fire district announced that New Square would remain in the fire district. Christopher St. Lawrence, the Town of Ramapo supervisor, said that the town is considering a "public safety loan program" to help New Square residents install life safety devices such as smoke alarms and sprinkler systems.[25]

In 1989, New Square funded their own health clinic, called Refuah Health Center. The New Square Cemetery is located on Bais Hachaim Way.[26] The village has a Hatzalah ambulance service branch, part of the Rockland County chapter, and has a public safety department that patrols the village.

New Square is within the 95th Assembly District in the New York State Assembly, which is represented by Ellen Jaffee.[27] New Square is within Senate District 38 in the New York State Senate, which is represented by David Carlucci.[28]

Community norms

There is a strong expectation that residents of New Square will conform to community norms; for example, by worshiping at the community's synagogue[29] and conforming to the Hasidic lifestyle.[30] Generally, conformity by those who do not comply voluntarily is enforced by the powers of the kehillah, a council appointed by the rebbe, whose members control most community institutions.[31] Those who have not conformed voluntarily have faced vigilante justice, as exemplified by the New Square arson attack and other incidents. The rebbe has denounced this practice, saying, "The use of force and violence to make a point or settle an argument violates Skver's most fundamental principles."[31][32]

Education

Although the town is within the East Ramapo Central School District,[33] all children of New Square attend the local private Jewish pre-K-12 schools, Avir Yaakov Boys School and Avir Yaakov Girls School.[34]

Controversies

Fraudulent grant controversy

Four Hasidic men from New Square, Benjamin Berger, Jacob Elbaum, David Goldstein, and Kalmen Stern, created a non-existent Jewish school and enrolled thousands of students, to receive US$30 million in education grants, subsidies, and loans from the U.S. federal government. Some of the money were used to enrich themselves, but also to benefit the community institutions.[35][36] The fraud scheme in New Square was tied into larger schemes in other ultra-Orthodox communities in Brooklyn and across the country.[37] The men were convicted in 1999. In October of that year, all four men received prison sentences ranging from 30 months to 78 months. Two other suspects who were indicted left the United States.[38] The indictment drew sharp criticism in New Square. A statement by village representatives accused authorities of having a vendetta against New Square residents, and acting "in a manner remindful of the Holocaust", during the investigations.[36]

Hillary Clinton met with New Square-area Hasidic leaders as part of her Senate campaign. Michael Duffy and Karen Tumulty of Time magazine said that "as far as anyone knows, that was a campaign event only; no pardons were mentioned". Hillary Clinton attended another session with the men, who wanted to see the four Hasidic leaders released. After Hillary Clinton was voted in as a senator, during the morning of December 22, Twersky and an associate visited Bill Clinton in the White House Map Room in Washington, D. C., and asked him to pardon the four men. Hillary Clinton attended the meeting; she said that she did not participate in it and did not discuss the meeting with her husband.[39]

On January 20, 2001, President Clinton commuted the sentences of the men; Berger's sentence became two years, and the other men each had 30 months. Federal prosecutors investigated the pardons to see if they were made in exchange for political support.[38] A 2001 ABC News article stated that some people wondered whether the pardons occurred as a kind of favor because the Village of New Square had voted overwhelmingly for Hillary Clinton for her first senate term (1359 out of 1369 votes – in contrast to two other Hasidic communities nearby who voted overwhelmingly Republican) – or if the pardons occurred as part of a quid pro quo swap for votes.[35][39][37] Hillary Clinton said that she was not involved in the pardons, and that her husband pardoned the men out of clemency.[38] In 2002 the prosecutors closed the investigation with no action.[40]

Kiryas Square

Due to population growth and a housing shortage in New Square, the Skver Hasidim had plans to expand to a new 400-acre (1.6 km2) village named Kiryas Square in the hamlet of Spring Glen, New York.[41] The property, the former Homowack Resort, was purchased by the Skver community in 2006.[42] Dedication of the site was in August 2007.[43] The New York State Department of Health cited the property which was used as a summer camp for girls for "numerous, persistent, and serious violations", including inoperable fire alarms, pervasive mold, and water running over electrical boxes. The health department issued a mandatory order of evacuation. In addition to problems with the health department, some local residents have also voiced opposition to the building of a Hasidic village. The site was evacuated in August 2009 as a result of a judge's deadline.[41]

See also

- Kaser, New York − an all-Hasidic village in the same county.

- Kiryas Joel, New York − an all-Hasidic village in a neighboring county.

- Qırmızı Qəsəbə

- Chernobyl (Hasidic dynasty)

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): New Square village, New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- New Square village, New York | QuickFacts

- "Mystics in the Suburbs". TIME. March 3, 1961.

- Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, ed. (2007). "New Square". Encyclopaedia Judaica. 15 (2 ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 189.

- Mintz, Jerome R. (1992). Hasidic People: A Place in the New World. Harvard University Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 9780674041097.

- MATTER OF UNGER v. NUGENT

- Lieberman, Steve (2015-08-03). "New Square Mayor Mates Friesel dies at 91". The Journal News. Retrieved 2015-08-24.

- New Square community profile

- Mintz, Jerome R. (1992). Hasidic People. A Place in the New World. Harvard University Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 9780674041097.

- Weiss, Steven I. (October 14, 2005). "Hasidic Village Keeps Women Out of the Driver's Seat". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- Foderaro, Lisa (August 20, 2003). "New York Town Mourns a Generous Friend". The New York Times.

- Mintz, Jerome R. (1992). Hasidic People. A Place in the New World. Harvard University Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 9780674041097.

- "V. of New Square Sidewalk and Curb Construction Project Archived 2009-03-26 at the Wayback Machine." New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal. 2008.

- V. of New Square expansion of Aim B'yisroel Archived 2009-03-26 at the Wayback Machine." New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal. 2007.

- Stebbins, Samuel; Sauter, Michael B. "Which town in your state is the poorest? Here is the list". USA TODAY.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Jewish Upstate Directory, 2005-2006

- Zeliger, Robert (August 31, 2007). "Culture clash". Rockland Magazine.

- Clarke, Suzan. "Water tower targets Hillcrest, New Square." The Journal News. November 17, 2008.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Modern Language Association, Data center results for New Square, New York. Retrieved on 2008-03-26.

- "Fire service to New Square won’t be interrupted Archived 2009-08-03 at the Wayback Machine." The Journal News. April 4, 2007.

- Cemetery Listing, Misaskim. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "Assemblymember Ellen Jaffee 95th Assembly District." New York State Assembly. Retrieved on November 14, 2008.

- "Map of NY Senate District 38 Archived 2008-11-02 at the Wayback Machine." Thomas P. Morahan. Retrieved on November 14, 2008.

- Applebome, Peter (June 5, 2011). "In Hasidic Village, Attempted Murder Arrest Is Linked to Schism". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

a rabbinical court ruled that praying outside the synagogue was a serious violation of community rules.

- Deen, Shulem (May 30, 2011). "What Is Really Happening in New Square?" (Opinion). The Jewish Daily Forward (June 10, 2011). Retrieved June 6, 2011.

There had been rumors in the study hall that the student in question was in possession of items forbidden by the rules of our austere Hasidic lifestyle.

- Tobin, Andrew (June 8, 2011). "New Square: Where Tradition and the Rebbe Rule: And Difference Comes at a Painful Cost". The Jewish Daily Forward (June 17, 2011). Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Shawn Cohen; Steve Lieberman (June 4, 2011). "Group of devotees enforces obedience to grand rebbe in New Square, residents say". The Journal News. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

Residents who defy this Hasidic enclave's spiritual leader say they live in fear of a band of thugs who sometimes violently defend his edicts

- Clark, Amy Sarah (2014-06-18). "East Ramapo Schools Under State Supervision". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- "Directory of Non-Public Schools Archived 2007-03-14 at the Wayback Machine." East Ramapo Central School District. Retrieved on November 13, 2008.

- "Questions Mount in Pardon Saga." ABC News. February 4, 2001. 1.

- Benjamin Weiser: 6 Indicted in Fraud Over Use of Grants For Hasidic Groups New York Times, May 29, 1997.

- Larry Cohler-Esses:U.S. Att'y Ripped Hasidic Pardons New York Daily News, January 25, 2001.

- Anderson, Nick. "Hasidic Clemency Case Entangles Hillary Clinton." Los Angeles Times. February 24, 2001.

- Duffy, Michael and Karen Tumulty. "Pardon Me, Boys." TIME. Sunday February 25, 2001. 1.

- "Has Clinton been vindicated?." CNN. June 24, 2002.

- Dube, Rebecca (August 12, 2009). "Hasidim Evacuate Catskills Camp Site, Leaving Plans for New Town in Doubt". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- Adam Bosch (May 29, 2008). "Orthodox group quietly plans new village". Times Herald-Record.

- Dan Hust (October 12, 2007). "Planned Hasidic 'city' At Former Homowack Causes Stir in Township". Sullivan County Democrat.