Kingdom of Munster

The Kingdom of Munster (Irish: Ríocht Mhumhain) was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland which existed in the south-west of the island from at least the 1st century BC until 1118. According to traditional Irish history found in the Annals of the Four Masters, the kingdom originated as the territory of the Clanna Dedad (sometimes known as the Dáirine), an Érainn tribe of Irish Gaels. Some of the early kings were prominent in the Red Branch Cycle such as Cú Roí and Conaire Mór. For a few centuries they were competitors for the High Kingship or Ireland, but ultimately lost out to the Connachta, descendants of Conn Cétchathach. The kingdom had different borders and internal divisions at different times during its history.

Kingdom of Munster Mumhain | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st century BC–1118 | |||||||||||

The Mac Cárthaigh as leaders of the Eóganacht Chaisil provided many kings of Munster from the 7th century onwards and established Cork.

| |||||||||||

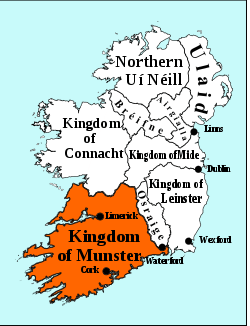

A map of Munster in the 10th century, with boundaries accounting for the loss of Osraige. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Cork | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Primitive Irish, Old Irish, Middle Irish, Latin | ||||||||||

| Religion | Gaelic Christianity Catholic Christianity Gaelic tradition | ||||||||||

| Government | Tanistry | ||||||||||

| Rí | |||||||||||

• 1st century BCE | Deda mac Sin | ||||||||||

• 1118 | Muirchertach Ó Briain | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1st century BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1118 | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IE | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Major changes reshaped Munster in the 7th century, as the Corcu Loígde (ancestors of the Ó hEidirsceoil) fell from power. Osraige which had been brought under the control of Munster for two centuries was retaken by the Dál Birn (ancestors of the Mac Giolla Phádraig). Various subordinate groups, such as the Múscraige, switched their alliance and helped to bring the Eóganachta to power in Munster. For the next three centuries, various subgroups such as the Eóganacht Chaisil (ancestors of the Ó Súilleabháin and Mac Cárthaigh)[1] and Eóganacht Glendamnach (ancestors of the Ó Caoimh) competed for control of Munster. Celtic Christian civilisation developed at this time and the Rock of Cashel became a seat of power. Two kings, Faílbe Flann mac Áedo Duib and Cathal mac Finguine, were able to raise Munster to the premier Irish kingdom for a time.

Munster had to contend with raids from the Vikings under the Uí Ímair from the 9th century onwards, who established themselves at Limerick, Waterford and Cork. Around the same time the Dál gCais (ancestors of the Ó Briain),[2] previously known as the Déisi, were also in the ascendancy in Munster. Aided in part by the Uí Néill, the previously subordinate Dál gCais came to challenge the Eóganachta for control of Munster. The exploits of their most famous member Brian Bóruma, who is known for the Battle of Clontarf established Dál gCais rule for the rest of the 11th century. After internal divisions, Munster was partitioned by High King Toirdelbach Ó Conchobhair with the Treaty of Glanmire in 1118, between Thomond ruled by the Ó Briain and Desmond ruled by the Mac Cárthaigh.

Etymology

A late medieval text in Middle Irish named Cóir Anmann (known in English as the "Fitness of Names" or the "Elucidation of Names") gives an etymology for the term Munster. It claims that the name partly derives from Eochaidh Mumu, one of the early Heberian High Kings of Ireland who ruled the area.[3] This High King held the royal nickname mó-mó meaning "greater-greater", because he was supposed to be more powerful and greater in stature than any other Irishman of his time (the Annals of the Four Masters claims he reigned from 1449–1428 BC).[3] The Cóir Anmann claims that the word mó (greater) with ána (prosperity) combined to form Mumu, because the kingdom was more prosperous than any other in Ireland.[3] The second word ána is also associated with the goddess Anu (potentially the same as mother goddesss Danu). Indeed, Munster includes within it a pair of breast shaped mountains near Killarney named the Two Paps of Ána.[3]

History

Rise of the Dáirine in Munster

The early Kings of Munster, derived from the Érainn (one of the major sub-branches of Gaels in Ireland), were mentioned in the Red Branch Cycle of Irish traditional history. Prominent figures featuring in this Cycle are Cú Roí mac Dáire, Conaire Mór, Lugaid mac Con Roí and others. These men are all presented as great warriors, in particular Cú Roí features in the Táin bó Cúailnge, where he fights Amergin mac Eccit, until requested to stop by Meadhbh. Eventually Cú Roí is killed by Cú Chulainn after being betrayed by Bláthnat who he had captured. His death was avenged by his son Lugaid mac Con Roí.

The Dáirine (named for Dáire mac Dedad), or Clanna Dedad, a major branch of the Érainn, were a significant power in Gaelic Ireland, providing several High Kings of Ireland at the Hill of Tara in addition to ruling Munster. There was also a Temair Luachra ("Tara of the Rushes"), existing as the royal site of Munster, but this is lost to history (it is potentially synonymous with Caherconree). Some of the most prominent High Kings from this time provided by the Érainn of Munster include Eterscél Mór and Conaire Mór who are the subject of the Togail Bruidne Dá Derga. The Laigin in particular were major rivals for Munster at the time. The Chronicle of Ireland places the start of these rulers at roughly the 1st century BCE. Outside of Gaelic sources, the predominant people of Munster, the Érainn, along with other tribes in the area are attested to in Ptolemy's Geographia, where they are known as the Iverni.

According to the Book of Glendalough, a member of the Munster royal family, Fíatach Finn, moved north and became King of Ulster, establishing the Érainn kindred known as the Dál Fiatach. This meant competing with the Ulaid rulers of Clanna Rudhraighe. A great revival of power for Munster occurred in the 2nd century AD, as one of their kings, Conaire Cóem, established himself as High King of Ireland. This was a time for pioneering figures, as major High Kings representing other Gaelic groups in Ireland also lived such as Conn Cétchathach founder of the Connachta and Cathair Mór a prominent king of the Laigin. Conaire Cóem holds an important place in Irish genealogies as the forefather of the Síl Conairi. His sons; Cairpre Músc (ancestor of the Múscraige and Corcu Duibne), Cairpre Baschaín (ancestor of the Corcu Baiscind) and Cairpre Riata (ancestor of the Dál Riata) founded kinship groups which would play a major role in Munster, while the latter moved north to Ulster and eventually established Alba (better known as Scotland) in Great Britain.

Another High King from Munster's Dáirine around this period was Lugaid Mac Con, the progenitor of Corcu Loígde. His mother was Sadb ingen Chuinn from the Connachta and he was called Mac Con ("Son of the Hound") because he was supposedly suckled by his foster-father Ailill Aulom's greyhound. He ascended to the High Kingship from his Munster base after killing Art mac Cuinn in the Battle of Maigh Mucruimhe, which is the subject of a literary tale. His foster-father, Ailill Aulom is claimed to have been a King of Munster and belonged to the Deirgtine. This group of Gaels were not Dáirine and other Kings of Munster from them mentioned in the Cycles of the Kings, include Mug Nuadat, Éogan Mór and Fiachu Muillethan. The exact relationship of the Deirgtine to other groups in Munster is controversial, the Eóganachta later claimed direct descent from them. The Eóganachta emerged in the 4th century under Corc mac Luigthig but would take power in the 7th century and the genealogical claim may have been to bolster their legitimacy.

Christianisation of the Realm

The religion of Christianity, which after the Edict of Thessalonica in 380 AD became the state religion of the Roman Empire and thus, much of Europe, came to Ireland in the 5th century, largely through Munster and Leinster. Many of the earliest saints of Ireland mentioned in the Codex Salmanticensis had strong Munster connections, particularly St. Ailbe in Emly, historical location of the Mairtine. He supposedly received canonical orders from St. Palladius who was sent by Pope Celestine I to Ireland in 431 AD.[4] The first Christian saint born in Ireland itself was St. Ciarán of Saigir, associated with Osraige, who had a royal Munster (Corcu Loígde) mother. As well as this St. Declán of the Déisi Muman converted his people and established a monastery at Ardmore.

The conversion of the Eóganacht Chaisil, who were Kings of Cashel and gaining more and more influence in Munster, to the detriment of the Corcu Loígde, occurred during the reign of Óengus mac Nad Froích. He was said to have been converted by St. Patrick in a ceremony in which Patrick is supposed to have accidentally pierced the king's foot with his crozier, a pain which Óengus stoically bore, presuming it was part of baptism.[5] Indeed, the very finding of Cashel, which was originally in the land of the Éile and its establishment as the base of the Eóganachta is attributed in the texts Acallam na Senórach and Senchas Fagbála Caisil to a miraculous "vision" of St. Patrick, sixty years beforehand by Corc mac Luigthig. According to the Acallam, Óengus then levied a tri-annual tribute in Munster known as the "scruple of Patrick’s baptism", showing a clear political interest (this was exacted until the times of St. Cormac mac Cuilennáin).[6]

Some of the earliest sites of Irish monasticism are to be found in Munster. St. Finnian of Clonard founded a monastery at Skellig Michael off the coast of the Iveragh Peninsula, St. Senán mac Geirrcinn founded a monastery at Inis Cathaigh as patron of the Corcu Baiscind and St. Enda of Aran founded the Killeaney monastery on Inishmore, with the support of Óengus mac Nad Froích. These monks often chose isolated and harsh locations for their monasteries, exhibiting an ascetic spirituality, similar to that of the Desert Fathers in Christian Egypt. Elsewhere, monasteries were founded more inland, such as the abbey at Lismore founded by St. Mo Chutu and the monastery at what was then known as the Corcach Mór na Mumhan (now the City of Cork) founded by St. Finbarr. The latter institution was particularly associated with learning. Both St. Brendan of Birr and St. Brendan of Clonfert came from Munster families, the latter was born in the land of the Ciarraighe Luachra. A noted female Munster saint of the day, St. Íte of Killeedy, was known as the "Brigid of Munster."

Age of the Eóganachta

By the 7th century, the Eóganachta had eclipsed the Corcu Loígde and all others for hegemony in Munster. They were aided in this by their allies, the Múscraige, who switched sided against their distant Érainn cousins, the Corcu Loígde. In a wider context, in Ireland at the time, the Uí Néill were firmly establishing themselves as the main power in the country, as the Érainn were in decline, the Laigin limited and the Eóganachta just establishing their hold over Munster.[7] A geopolitical reality, based on the Leath Cuinn and Leath Moga divisions was then being established. Under Faílbe Flann mac Áedo Duib, Munster crossed the River Shannon and defeated the Ui Fiachrach Aidhne of Connacht, taking from them what would become Thomond (or in much later times County Clare) and settling it with Déisi. This king of Munster was even able to project power and influence the choice of kings beyond his realm in neighbouring Leinster. With the fall of the Corcu Loígde, Osraige returned to the Mac Giolla Phádraig, but remained a túatha of Munster until the 9th century.

In regards to the Eóganachta themselves, there were two main branches; the most powerful was the "inner circle", or the eastern-branch, which was further divided into the Eóganacht Chaisil, Eóganacht Glendamnach, Eóganacht Áine and Eóganacht Airthir Cliach.[8] The "outer circle" consisted of the Eóganacht Raithlind and Eóganacht Locha Léin who were more the west and south. Despite supposedly being descended from a different lineage (that of Dáire Cerbba), the Uí Liatháin and Uí Fidgenti are sometimes lumped in with the latter group. According to the Frithfolaid ríg Caisil fri túatha Muman, only the patrilineal descendants of Nad Froích had the right to be King of Munster.[8]

Indeed, for the most part this would be the case as the Eóganacht Chaisil (ancestors of the Ó Súilleabháin and Mac Cárthaigh), Glendamnach (ancestors of the Ó Caoimh) and Áine (ancestors of the Ó Ciarmhaic) would provide the overwhelming majority of the kings. Despite the size of their kingdom, Munster was usually substantially weaker than the norther Uí Néill powerhouse; the Eóganachta built up a propaganda that they ruled through "prosperity and generosity", rather than just brute force.[8] Aside from the aforementioned Faílbe Flann, another exception to this general rule was Cathal mac Finguine from Glanworth established himself as a serious contender for the title of High King of Ireland and fought against a succession of three Uí Néill kings for hegemony; Fergal mac Máele Dúin, Flaithbertach mac Loingsig and Áed Allán. He would be the most powerful king from Munster until Brian Bóruma in the 11th century.

Viking raids and longphorts

The Vikings; Norsemen from Scandinavia; began to raid isolated Irish monasteries in their longboats from the late 8th century onwards. Specifically relevant for Munster were the raids at Inish Cathaigh (816 and 835) and Skellig Michael (824).[9] The raiders chose these monasteries primarily because they were isolated and easy to attack from the Sea; they took provisions, precious goods (metalwork especially), livestock and human captives (these people were either ransomed back if they were high-profile clerics or forced into slavery abroad).[10] In some cases in Ireland, by the mid-9th century, the Vikings set up coastal encampments known as longphorts; specifically in relation to Munster, this included; Waterford, Youghal, Cork and Limerick.[10] After first attacking neighbouring Gaelic Irish kingdoms and receiving retribution in return, the mercantile Vikings began to trade with the native Irish and some even intermarried, they also gradually converted to Christianity and eventually became Norse-Gaels, exhibiting elements of both cultures.

In Munster itself, a group from among the Vikings; the Uí Ímair, claiming descent from and named for Ivar the Boneless, son of Ragnar Lodbrok; eventually emerged as Kings of small Norse-Gaelic kingdoms where they were Kings of Limerick and Kings of Waterford. These small kingdoms; amongst which Limerick was the most prominent; were involved in rivalries with other Vikings in Ireland and held a complex web of rivalries and alliances with native Irish Gaelic clans.[10] The cultural influence wasn't all one way; some native Irish families in Munster adopted personal names and eventually clan names of Old Norse origin. This includes Mac Amhlaoibh, with Amhlaoibh meaning Olaf.[10] A prominent example of a Viking-Gaelic alliance in Munster was when the Waterford Vikings joined with Cellachán Caisil, a King of Munster from the Eóganacht Chaisil in 939 against Donnchadh Donn, who was then the High King of Ireland from the southern Uí Néill.[10]

The impact of the Vikings, along with pressure from Clann Cholmáin (i.e. the Uí Néill, who dominated the High Kingship of Ireland at the time) led to instability within the Munster Kingship and even permanently broke Osraige from its overkingship. The ascent of elements outside of the main royal families occurred, for instance; St. Cormac mac Cuilennáin from a very much junior branch of the Eóganacht Chaisil became King of Munster during the early 10th century. Cormac and his right-hand man Flaithbertach mac Inmainén were able to inflict defeats on High King Flann Sinna after the latter had ravaged Munster in 906. As well as his martial prowess and religious piety, Cormac was known for his literacy, as his name appears on the Sanas Cormaic, an Irish language glossary. Cormac finally met his end at the Battle of Bellaghmoon, where his army was greatly outnumbered. After his severed head was brought to his great rival Flann Sinna, the High King is supposed to have said "It was an evil deed, to cut off the holy bishop's head; I shall honour it, and not crush it." Cormac was succeeded by Flaithbertach who was notably absent from the Battle. He was the only ever King of Munster from the Múscraige later known as the Ó Donnagáin.

Division into Desmond and Thomond

The power of the Eóganachta was challenged in the 10th century by the Dál gCais of Thomond (ancestors of the Ó Briain). They were assisted in this initially by the Uí Néill who wanted to weaken the Eóganachta. The most successful member of the Dál gCais was Brian Bóruma, who established himself not only as King of Munster, but also High King of Ireland and is remembered for his feats at the Battle of Clontarf against the Vikings. After the death of Brian, the Dál gCais dominated the Munster kingship for the duration of the 11th century uninterrupted; from the reign of Donnchadh Ó Briain until Brian Ó Briain. Two of these kings; Toirdelbach Ó Briain and Muirchertach Ó Briain; were also High Kings of Ireland. During the reign of Muirchertach, his grandfather Brian's feats were portrayed in the literary work Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib in a proto-Irish nationalist sense as a Gaelic war of liberation against the Viking invaders and their collaborators.

Towards the end of Muirchertach's reign, he fell ill. His brother Diarmaid Ó Briain who was powerful in Waterford (and had earlier been banished to Deheubarth in Britain), felt that he would make a better ruler. As well as this strife, all of the kingdoms which had become lesser powers to Munster; Connacht (under the Ó Conchobhair), Aileach (under the Mac Lochlainn) and Leinster (under the Mac Murchadh); saw this as their opportunity to claw back some power and raise their profile. Their old enemies with whom enmity had remained, the Mac Cárthaigh, under Tadhg Mac Cárthaigh had also reasserted power in the south-west of Munster (which was soon to be known as Desmond). In 1118, the new king of Munster, Brian Ó Briain led a force against Tadhg Mac Cárthaigh at the Battle of Glanmire. The result was victory for the Mac Cárthaigh and the death of Brian Ó Briain.

Upon hearing the news, the old king, Murichertach Ó Briain returned to claim Munster. However, the High King of Ireland, Toirdelbach Ó Conchobhair as part of a self-interested move to weaken Munster, agreed in the Treaty of Glanmire in 1118 with Tadhg Mac Cárthaigh to divide Munster in two. Thus, Munster was partitioned into Thomond (ruled by the Ó Briain) and Desmond (ruled by the Mac Cárthaigh), putting to an end a kingdom which had existed for over 1,000 years. Until the end of the 12th century, representatives of each side made claims to the Munster kingship but it did not exist in reality. These kingdoms withstood the invasion of the Normans in Ireland with varying success but eventually in the 16th century were brought under the English Crown in Ireland. The last surviving Munster-derived Gaelic realm was Carbery under the Mac Cárthaigh Riabhach, a derivative of Desmond which fell as late as 1606. The name Munster itself was later revived as the Province of Munster as part of the Tudor-ruled Kingdom of Ireland in the 16th century.

Kingship

See also

- Annals of Inisfallen

- An Leabhar Muimhneach

- Leabhar na Núachongbhála

- Uraicecht Becc

- Knockgraffon

References

- "MacCarthy Mor (No. 1.)". LibraryIreland.com. Retrieved on 26 July 2009.

- "O'Brien (No. 1.) King of Thomond". LibraryIreland.com. Retrieved on 26 July 2009.

- "Cóir Anmann". Celtic Literature Collective. 25 March 2019.

- "Christianity Arrives In Ireland". Your Irish Culture. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

- "Cashel". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

- "Rhetorical Re-tellings: Senchas Fagbála Caisil and Twelfth-Century Church Reform in Ireland". Brian J. Stone, Quaestio Insularis, Volume 12. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

- "Ireland's History in Maps (500 AD)". Dennis Walsh. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

- "Tochmarc Momera: an edition and translation, with introduction and textual notes". Utrecht University Repository. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

- "Ireland's History in Maps (800 AD)". Dennis Walsh. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

- "The Vikings in Munster" (PDF). University of Nottingham. Retrieved on 26 July 2017.

Bibliography

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2007). Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521037167.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Byrne, Francis J. (1973). Irish Kings and High Kings. Four Courts Press. ISBN 1851821961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ellis, Peter Berresford (2002). Erin's Blood Royal: The Gaelic Noble Dynasties of Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312230494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gleeson, John (1927). Cashel of the Kings: A History of the Ancient Capital of Munster from the Date of Its Foundation Until the Present Day. J. Duffy & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnston, Elva (May 2008) [Sept 2004], "Munster, saints of (act. c.450–c.700)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 14 December 2008

- Koch, John T. (2004). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851094400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCullough, David W. (2010). Wars of the Irish Kings: A Thousand Years of Struggle, from the Age of Myth through the Reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 0307434737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Conor Don, Charles (1753). Dissertations On the Ancient History of Ireland. J. Christie.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (2005). A New History of Ireland, Volume I: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199226658.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Duffy, Séan (2005). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 1135948240.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ó Flaithbheartaigh, Ruaidhrí (1685). Ogygia: A Chronological Account of Irish Events. B. Tooke.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Halloran, Sylvester (1778). A General History of Ireland. Hamilton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Halloran, W (1916). Early Irish History and Antiquities and the History of West Cork. Sealy, Bryers and Walker.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (2001). The Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in Pre-Christian Ireland. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851157474.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Keeffe, Eugene (1703). Eoganacht Genealogies from the Book of Munster. Cork.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stone, Brian James (2011). "Rhetorical Re-tellings: Senchas Fagbála Caisil and Twelfth-Century Church Reform in Ireland". Quaestio Insularis. 12: 109–125.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Kingdom of Mumha, or Munster at Aughty

- Chief Irish Families of Munster at Library Ireland

- Munster at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Corcu Loígde DNA Project at Family Tree DNA

- Tribes & Territories of Mumhan

- Annals of Munster