Kasha (folklore)

The kasha (火車, lit. "burning chariot" or "burning barouche" or 化車, "changed wheel") is a Japanese yōkai that steals the corpses of those who have died as a result of accumulating evil deeds.[1][2]

Summary

Kasha are a yōkai that would steal corpses from funerals and cemeteries, and what exactly they are is not firmly set, and there are examples all throughout the country.[1] In many cases their true identity is actually a cat yōkai, and it is also said that cats that grow old would turn into this yōkai, and that their true identity is actually a nekomata.[1][3] However, there are other cases where the kasha is depicted as an oni carrying the damned in a cart to hell.[4]

There are tales of kasha in tales like the folktale Neko Danka etc., and there are similar tales in the Harima Province (now Hyōgo Prefecture), in Yamasaki (now Shisō), there is the tale of the "Kasha-baba."[2]

As a method of protecting corpses from kasha, in Kamikuishiki, Nishiyatsushiro District, Yamanashi Prefecture (now Fujikawaguchiko, Kōfu), at a temple that a kasha is said to live near, a funeral is performed twice, and it is said that by putting a rock inside the coffin for the first funeral, this protects the corpse from being stolen by the kasha.[5] Also, in Yawatahama, Ehime, Ehime prefecture, it is said that leaving a hair razor on top of the coffin would prevent the kasha from stealing the corpse.[6] In Saigō, Higashiusuki District, Miyzaki Prefecture (now Misato), it is said that before a funeral procession, "I will not let baku feed on this (バクには食わせん)" or "I will not let kasha feed on this (火車には食わせん)" is chanted twice.[7] In the village of Kumagaya, Atetsu District, Okayama Prefecture (now Niimi), it is said that a kasha is avoided by playing a myobachi (妙八) (a traditional Japanese musical instrument).[8]

Japanese folklore often describes the Kasha as humanoid cat-demons with the head of a cat or tiger and a burning tail. They are similar to other demons such as Nekomata and Bakeneko and get often interchanged with them. Kashas are said to travel the world on burning chariots or barouches, stealing the corpses of recently deceased humans, which were not yet buried and who had been sinful in life. They bring their souls to hell.[9][10][11]

Kasha in classics

- "Concerning How in the Manor of Ueda, Echigo, at the Time of Funeral, a Lightning Cloud Comes and Steals Corpses" from the "Kiizō Danshū" (奇異雑談集)

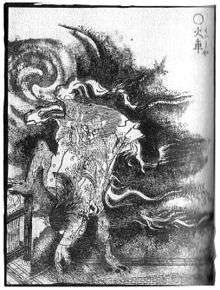

- In funerals performed in Ueda, Echigo, a kasha appeared during the funeral presence, and attempted to steal the corpse. It is said that this kasha appeared together with harsh lightning and rain, and in the book's illustration, like the raijin, it wears a fundoshi made with a tiger's skin, and is depicted possessing a drum that can cause lightning (refer to image).[12]

- "Holy Priest Onyo Himself Rides with a Kasha" from the "Shin Chomonjū (新著聞集)," Chapter Five "Acts of Prayer"

- In Bunmei 11, July 2, at the Zōjō-ji, Holy Priest Onyo was greeted by a kasha. This kasha was not an envoy of hell, but rather an envoy of the pure land, and thus here, the appearance of a kasha depended on whether or not one believed in the afterlife.[13][14]

- "Looking at a Kasha, Getting Sore at the Waist and Legs, and Collapsing" from the "Shin Chomonjū", Chapter Ten "Strange Events"

- It was at the village of Myōganji near Kisai in Bushū. One time, a man named Yasubei who ran an alcohol shop suddenly ran off down a path, shouted "a kasha is coming," and collapsed. By the time the family rushed to him, he had already lost his sanity and was unable to listen to anything said to him, fell asleep, and it is said that ten days later, his lower body started rotting and he died.[15]

- "Cutting the Hand of an Ogre in a Cloud at the Place of Funeral" from the "Shin Chomonjū", Chapter Ten "Strange Events"

- When a warrior named Matsudaira Gozaemon participated in the funeral procession of his male cousin, thunder began to rumble, and from a dark cloud that covered the sky, a kasha stuck out an arm of one like a bear, and attempted to steal the corpse. When it was cut off by a sword, it was said that the arm had three dreadful nails, and was covered by hair that looked like silver needles.[14][15]

- "A Kasha Seizes and Takes Away an Avaricious Old Woman" from the "Shin Chomonjū", Chapter Fourteen "Calamities"

- When a feudal lord of Hizen, the governor of Inaba, Oomura, and several others, were going around the seacoast of Bizen, a black cloud appeared from afar, and echoed a shreik, "ah, how sad (あら悲しや)," and a peron's feet stuck out from the cloud. When the governor of Inaba's retinue dragged it down, it turned out to be the corpse of an old woman. When the people in the surroundings were asked about the circumstances, it turned out that the old woman was terribly stingy, and was detested by those around her, but one time when she went outside to go to the bathroom, a black cloud suddenly swooped down and took her away. To the people of that society, it was the deed of a devil called "kasha."[14][16]

- "Kasha" from the "Bōsō Manroku" (茅窓漫録)

- It would sometimes happen that in the middle of a funeral procession, rain and wind would suddenly come forth, blow away the coffin, and cause the corpse to be lost, but this was due to how a kasha from hell came to greet it, and caused people to be afraid and feel ashamed. It is said that the kasha would tear up the corpse, hang it on rocks or trees in the mountains. In the book, there are many kasha in Japan and in China, and here it was the deed of a beast called Mōryō (魍魎), and in the illustration, it was written as 魍魎 and given the reading "kuhashiya" (refer to image).[14][17]

- "Priest Kitataka" from the Hokuetsu Seppu

- It was in the Tenshō period. At a funeral in the Uonuma District, Echigo Province, a sudden gust and a ball of fire came flying to it, and covered the coffin. Inside the ball of fire, was a giant cat with two tails, and it attempted to steal the coffin. This yōkai was repelled by the priest of Dontōan, Kitataka, by his incantation and a single strike of his nyoi, and the kesa of Kitagawa was afterwards called the "kasha-otoshi no kesa" (the kesa of the one who defeated a kasha).[18]

Similar things to kasha

Things of the same kind as kasha, or things thought of as a different name for kasha, are as following.[1]

In Tōno, Iwate Prefecture, called "kyasha," at the mountain next to the pass that continued from the village of Ayaori, Kamihei District (now part of Tōno) to the village of Miyamori (now also part of Tōno), there lived a thing that took on the appearance of a woman who wore a kinchaku bag tied to her front, and it is said that it would steal corpses from coffins at funerals and dig up corpses from the gravesites and eat the corpses. In the village of Minamimimaki, Nagano Prefecture (now Saku), it is also called "kyasha," and like usual, it would steal corpses from funerals.[19]

In the Yamagata Prefecture, a story is passed down where when a certain wealthy man died, a kasha-neko (カシャ猫 or 火車猫) appeared before him and attempted to steal his corpse, but the priest of Seigen-ji drove it away. What was then determined to have been its remaining tail was then presented to the temple of Hase-kannon as a charm against evil spirits, which is open to the public on new years each year.[20]

In the village of Akihata, Kanra District, Gunma Prefecture (now Kanra), a monster that would eat human corpses are called "tenmaru," and in order to defend against this, the bamboo basket on top was protected.[21]

In Himakajima, Aichi Prefecture, kasha are called madōkusha, and it is said that a cat that would reach one hundred years of age would become a yōkai.[22]

In the Izumi region, Kagoshima Prefecture, called "kimotori," they are said to appear at the gravesite after funerals.[3]

Development of the term and concept of Kasha over time

Kasha literally means “burning cart” or “fiery chariot”. During Japan's Middle Ages and early modern era, Kasha were depicted as a fiery chariot who took the dead away to hell, and were depicted as such in Buddhist writings, such as rokudo-e.[4] Kasha also appeared in Buddhist paintings of the era, notably jigoku-zōshi (Buddhist ‘hellscapes’, paintings depicting the horrors of hell), where they were depicted as flaming carts pulled by demons or oni.[23][24] The tale of the kasha was used by the Buddhist leadership to persuade the populace to avoid sin.[4]

It was said that during the funeral procession of a sinful man, the kasha would come for the body.[25] When kasha arrived, they were accompanied by black clouds and a fearsome wind.[25][4] These great winds would be strong enough to lift the coffin into the sky, out of the hands of those bearing it on their shoulders. When this occurred, the pallbearers would explain it as the body having been “possessed by the kasha”[26]

The legends state that if a monk is present in the funeral procession, then the body could be reclaimed by the monk throwing a rosary at the coffin, saying a prayer, or signing their seal onto the coffin.[25][4] The remedy for a kasha corpse abduction varies by region and source. However, if no monk was present or no rosary thrown, then the coffin and body lying therein were taken away to hell.[25] Alternatively, the body would be disrespected by the kasha by being savagely torn into pieces and hung on adjacent tree limbs or rocks.[27]

Over time, the image of the kasha evolved from a chariot of fire to a corpse-stealing cat demon that appeared at funerals. It is not clear how or when the flaming cart demon and bakeneko were confounded, but in many cases, kasha are depicted as cat demons, often wreathed in flame.[26][28] This has led to the modern-day conception of the kasha as one variety of bakeneko, or ‘monster cats’.[28]

There is some considerable discussion on the origin of the feline appearance of the modern kasha. Some believe that the kasha was given a feline appearance when the previous conception of the kasha was given the attributes of another corpse-robbing yokai, the Chinese Mōryō or wangliang.[26][29] In the aforementioned "Bōsō Manroku," the characters 魍魎 were read "kuhashiya," in the essay Mimibukuro by Negishi Shizumori, in volume four "Kiboku no Koto" (鬼僕の事), there is a scene under the name, "The One Called Mōryō" (魍魎といへる者なり).[29]

In Japan, from old times, cats were seen as possessing supernatural abilities, and there are legends such as "one must not let a cat get near a corpse" and "when a cat leaps over a coffin, the corpse inside the coffin will wake up." Also, in the collection of setsuwa tales, the Uji Shūi Monogatari from medieval Japan, a gokusotsu (an evil ogre that torments the dead in hell) would drag a burning hi no kuruma (wheel of fire), it is said that they would attempt to take away the corpses of sinners, or living sinners. It has thus been determined that the legend of the kasha was born as a result of the mixture of legends concerning cats and the dead, and the legend of the "hi no kuruma" that would steal away sinners.[1]

Another popular viewpoint is that kasha were given the cat-like appearance after it was noted that in rare cases, cats will consume their deceased owners.[23] This is a rather unusual occurrence, but there are recorded modern cases of this.[30]

Another theory states that the legend of kappa making humans drown and eating their innards from their butts was born as a result of the influence of this kasha.[31][32]

Re-usage of the term

The Japanese Idiom "hi no kuruma", an alternate reading of 火車, "kasha", meaning "to be in a difficult financial situation" or "to be strapped for cash", comes from how the dead would receive torture from the kasha on their journey to hell.[33][34]

In the region of the Harima Province, old women with bad personalities are said to be called "kasha-baba" ("kasha old women"), with the nuance that they are old women that are like bakeneko.[2]

How the yarite, the woman who controls the yūjo in the yūkaku, is called "kasha" (花車, "flower wheel") comes from this kasha, and as the yarite was the woman who managed everything, and how the word "yarite" is also used to indicate people who move bullock carts (gissha or gyūsha) also comes from this.[3]

See also

- Gazu Hyakki Yakō

- Bakeneko

- Maneki-neko

- Nekogami

- Nekomata

References

- 村上健司 編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. pp. 103–104頁. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- 播磨学研究所編 (2005). 播磨の民俗探訪. 神戸新聞総合出版センター. pp. 157–158頁. ISBN 978-4-3430-0341-6.

- 京極夏彦・多田克己編著 (2000). 妖怪図巻. 国書刊行会. pp. 151頁. ISBN 978-4-336-04187-6.

- Nihon kaii yōkai daijiten. Komatsu, Kazuhiko, 1947-, Tsunemitsu, Tōru, 1948-, Yamada, Shōji, 1963-, Iikura, Yoshiyuki, 1975-, 小松和彦, 1947-, 常光徹, 1948- (Saihan ed.). Tōkyō-to Chiyoda-ku. July 2013. ISBN 9784490108378. OCLC 852779765.CS1 maint: others (link)

- 土橋里木. "甲斐路 通巻24号 精進の民話". 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース. 国際日本文化研究センター. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- 河野正文. "愛媛県史 民俗下巻 第八章 第三節:三 死と衣服". 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- 河野正文. "民俗採訪 通巻昭和38年度号 宮崎県東臼杵郡西郷村". 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- 桂又三郎. "中国民俗研究 1巻3号 阿哲郡熊谷村の伝説". 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- Michaela Haustein: Mythologien der Welt. Japan, Ainu, Korea. ePubli, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-8442-1407-9, page 25.

- Bokushi Suzuki: Snow country tales. Life in the other Japan. Translated by Jeffrey Hunter with Rose Lesser. Weatherhill, New York NY u. a. 1986, ISBN 0-8348-0210-4, page 316–317.

- Chih-hung Yen: Representations of the Bhaisajyaguru Sutra at Tun-huang. In: Kaikodo Journal. Vol. 20, 2001, ZDB-ID 2602228-X, page 168.

- 高田衛編・校中 (1989). "奇異雑談集". 江戸怪談集. 岩波文庫. 上. 岩波書店. pp. 230–232頁. ISBN 978-4-00-302571-0.

- 神谷養勇軒 (1974). "新著聞集". In 日本随筆大成編輯部編 (ed.). 日本随筆大成. 〈第2期〉5. 吉川弘文館. pp. 289頁. ISBN 978-4-642-08550-2.

- 京極夏彦・多田克己編著 (2000). 妖怪図巻. 国書刊行会. pp. 150–151頁. ISBN 978-4-336-04187-6.

- "新著聞集". 日本随筆大成. 〈第2期〉5. pp. 355–357頁.

- "新著聞集". 日本随筆大成. 〈第2期〉5. pp. 399頁.

- 茅原虚斎 (1994). "茅窓漫録". 日本随筆大成. 〈第1期〉22. 吉川弘文館. pp. 352–353頁. ISBN 978-4-642-09022-3.

- 鈴木牧之 (1997). "北高和尚". 北越雪譜. 地球人ライブラリー. 池内紀(trans.). 小学館. pp. 201–202頁. ISBN 978-4-09-251035-7.

- 柳田國男監修 民俗学研究所編 (1955). 綜合日本民俗語彙. 第1巻. 平凡社. pp. 468頁.

- 山口敏太郎 (2003). とうほく妖怪図鑑. んだんだブックス. 無明舎. pp. 40–41頁. ISBN 978-4-89544-344-9.

- 妖怪事典. pp. 236頁.

- 妖怪事典. pp. 312頁.

- Zack, Davisson (2017). Kaibyō : the supernatural cats of Japan (First ed.). Seattle, WA. ISBN 9781634059169. OCLC 1006517249.

- "Tokyo Exhibit Promises A Hell of An Experience". Japan Forward. 2017-08-05. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- Hiroko, Yoda; Alt, Matt (2016). Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yōkai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486800356.

- Shigeru, Mizuki (2014). Japanese Yōkai Encyclopedia Final Edition: Yōkai, Other Worlds and Gods (決定版 日本妖怪大全 妖怪・あの世・神様, Ketteihan Nihon Yōkai Taizen: Yōkai - Anoyo - Kami-sama). Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha-Bunko. ISBN 978-4-06-277602-8.

- 1712-1788, Toriyama, Sekien; 1712-1788, 鳥山石燕 (2017-01-18). Japandemonium illustrated : the yokai encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien. Yoda, Hiroko,, Alt, Matt,, 依田寬子. Mineola, New York. ISBN 978-0486800356. OCLC 909082541.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Meyer, Matthew. "Kasha". Retrieved Dec 5, 2018.

- 村上健司 編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. pp. 103–104頁. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- Sperhake, J.P (2001). "Postmortem Bite Injuries Cause by a Domestic Cat". Archiv Fur Kriminologie. 208 (3–4): 114–119 – via EBSCOhost.

- 妖怪図巻. pp. 147頁.

- 根岸鎮衛 (1991). 長谷川強校注 (ed.). 耳嚢. 岩波文庫. 中. 岩波書店. pp. 125頁. ISBN 978-4-00-302612-0.

- 多田克己 (2006). 百鬼解読. 講談社文庫. 講談社. pp. 52頁. ISBN 978-4-06-275484-2.

- "【火の車】の意味と使い方の例文(慣用句) | ことわざ・慣用句の百科事典". proverb-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

External links

- Short infos about Kashas (English)