Ittan-momen

Ittan-momen (一反木綿, "one bolt(tan) of cotton") are a yōkai told about in Kōyama, Kimotsuki District, Kagosima Prefecture (now Kimotsuki. They are also called "ittan monme" or "ittan monmen."[1]

Summary

According to the Ōsumi Kimotsukigun Hōgen Shū (大隅肝属郡方言集) jointly authored by the locally born educator, Nomura Denshi and the folkloricist Kunio Yanagita, at evening time, a cloth-like object about 1 tan in area (about 10.6 meters in length by 30 centimeters in width) would flutter around attack people.[1]

They are said to wrap around people's necks and cover people's faces and suffocate people to death,[2][3][4][5] and in other tales it is said that wrapped cloths would spin around and around and quickly come flying, wrap around people's bodies, and take them away to the skies.[6]

There is a story where one man hurrying to his home at night when a white cloth came and wrapped around his neck, and when he cut it with his wakizashi (short sword), the cloth disappeared, and remaining on his hands was some blood.[3]

In regions where they are said to appear and disappear, there seemed to be a custom where children were warned that if they play too late, that "ittan momen would come."[6]

Also, it is said that in Kimotsuki, there is are shrines (the Shijūkusho Jinja for example) where ittan momen are said to frequently appear, and it was believed that when children pass in front of the shrine, an ittan momen flying above in the skies would attack the very last child in line, so children would go run ahead and cut through.[7]

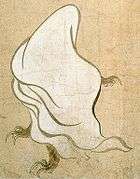

In the classical yōkai emaki, the Hyakki Yagyō Emaki, there is a yōkai shaped like a cloth with arms and legs, and the folklorist Komatsu Kazuhiko hypothesizes that this is the origin of ittan momen.[8]

Recent sightings

According to a report from the yōkai researcher Bintarō Yamaguchi, in recent years there have been many eyewitness reports of flying cloth-shaped objects thought to be ittan momen.[9]

In Kagoshima Prefecture where this legend is told, white cloth-like objects flying in low altitude have been witnessed. In Fukuoka Prefecture, also in Kyushu, there have been reports of extremely speedy ittan momen flying alongside shinkansen trains witnessed by shinkansen passengers.[9]

Outside Kyushu, there have been witness reports in Higashi-Kōenji Station and Ogikubo, Tokyo. In Higashi-Kōenji, a woman walking her dog witnessed a cloth flying in the skies and followed it for a while.[9]

In Shizuoka Prefecture, elementary school kids were said to have seen a transparent sheet-like object flutter around, and the entire object was like a rectangle, but it became thin on one end, like a tail.[9]

In 2004, in Hyōgo Prefecture, a UFO filming society captured footage of an unidentified cloth-shaped object flying in the skies above Mount Rokkō and it is said to be extremely large, at 30 meters.[9]

While filming Natsuhiko Kyogoku "Kai", the actor Shirō Sano witnessed an ittan momen flying above, and it is said to have a long white shape.[10]

Also, in the eastern Japan earthquake, there have been many reports of something closely resembling an ittan momen, and there have been many videos confirmed to show a white cloth-like object flying in the air.

True identity

Ittan momen are thought to appear in the evening, but the general view is that this is because in the past, parents needed to do farmwork for the entire day including at this time and therefore could not keep an eye on their children, so the tales of ittan momen were told to children to warn them of the dangers of playing too late.[1] Also, in the lands where the legend is told, there is a custom of raising a cotton flag during burials for the purpose of mourning, so it is inferred that some of these would be blown by the wind and fly in the air and thus be connected to the legends of the momen yōkai.[1]

In the Japanese television series Tokoro-san no Me ga Ten! there was an experiment performed in which a piece of cloth about 50 centimeters long was set up and moved in the darkness, and the average length reported by the people who saw it was 2.19 meters, with the longest being 6 meters. The program suggested that when a white or bright objects move in the darkness, a positive afterimage optical illusion would leave a trail due to movement, causing soaring things in the forests at night such as musasabi to be seen as longer than they actually are, and thus mistaken as ittan momen.[11]

In fiction

There are no depictions of ittan momen in classical yōkai emaki, so this yōkai was once relatively unknown, but ever since their appearance in Mizuki Shigeru's comic GeGeGe no Kitarō, it became more widely known.[12] This comic depicted them to talk in a Kyushu dialect, have good-natured personalities, and have a unique look while flying, which raised their fame and popularity despite their original legend of attacking people.[6][13] In Shigeru's birthplace, Sakaiminato, Tottori Prefecture, they ranked number 1 in the "First Yōkai Popularity Poll" held by the tourism association.[1][13]

Also, in Shigeru's yōkai depictions, like the other characters of Kitarō, they are depicted as a cloth with two eyes and two arms,[3] so now they are commonly perceived to be pieces of cloth with two eyes in yōkai depictions, but Mizuki's yōkai depictions are original inventions and the ones in actual legend and in the previous witness reports have no eyes or arms and are instead simply flying objects that resembled cloth.[14][15]

In Kamen Rider Hibiki, they appeared as enemy characters and they were based on the original legend with some extra original twists on their appearance and personality.[16]

In 2007, the local historian of Kagoshima Prefecture, Takenoi Satoshi, started creating kamishibai of ittan momen so that such legends that are gradually being forgotten can be remembered by the children.[1]

In the 2020 anime adaptation of the In/Spectre {"Kyokō Suiri") novels, an ittan momen drawn in the Mizuki style, flies out from under the skirt of the female protagonist Kotoko.

Similar yōkai

The following are yōkai considered to be similar to ittan momen.[2] The musasabi would through the air along forest streets at night and cling to people's faces in surprise, so it is theorized that they are thought to a yōkai like this.[17]

Fusuma ("bedding")

- A yōkai told to frequently appear and disappear on Sado Island in the Edo Period. It was a yōkai that looked like a large furoshiki, and they would come flying out of nowhere at roads at night and cover the heads of pedestrians. They cannot be cut with blades of any sharpness, but they can be bit apart with teeth that have been blackened at least once. It is said that because of this, there was a custom for males to blacken their teeth.[18]

Futon kabuse (literally, "cover with futon")

- Saku-shima, Aichi Prefecture. In the writings of the folkloricist Kunio Yanagita, it is only written that "they'd float along and flying in with a whoosh, covering and suffocating to death,"[19] so there are not many legends about it and not much is known,[20] but it is interpreted to be a futon-hsaped object that come flying in and covering people's faces and suffocating them to death.[21]

In popular culture

- In the anime/manga series Inu x Boku SS, one of the characters, Renshō Sorinozuka, is an Ittan-momen.

- In the tokusatsu franchise Super Sentai, the Ittan-momen was seen as a basis of a monster in series installments themed after Japanese culture:

- In Kakuranger (1994), one of the Youkai Army Corps members the Kakurangers fought was an Ittan-momen. It appeared in the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers toyline as "Calcifire".

- In Shinkenger (2009), one of the Ayakashi, named Urawadachi, served as the basis of the Ittan-momen within the series. He was not adapted into Power Rangers Samurai.

- In Ninninger (2015), one of the Youkai the Ninningers fought was an Ittan-momen, with elements borrowed from a carpet and a magician. It was later adapted into Power Rangers Ninja Steel as Abrakadanger who appears in his self-titled episode.

- In Yo-kai Watch, the Ittan-momen appears as a cloth-strip Yo-kai and is called So-Sorree in the English dub. Anyone inspirited by So-Sorree can become mischievous and then give insincere apologies. So-Sorree can evolve into Bowminos (a domino-shaped Yo-kai who makes anyone it inspirits give sincere apologies) and can be fused with Merican Flower to become Ittan-Sorry.

- In GeGeGe no Kitarō, a recurring yōkai character named Ittan Momen (Rollo Cloth in English translations) appears as an anthropomorphic cloth with the ability to fly. He is among Kitaro's core group of friends.

Notes

- 板垣 2007, p. 15

- 多田 1990, p. 107

- 水木 1994, p. 67

- Bush, Laurence (2001). Asian Horror Encyclopedia: Asian Horror Culture in Literature, Manga and Folklore. Lincoln, NE: Writers Club Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-595-20181-4.

- Frater, Jamie (2010). Listverse.com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists: Fascinating Facts and Shocking Trivia on Movies, Music, Crime, Celebrities, History and More. Berkeley, CA, USA: Ulysses Press. p. 534. ISBN 978-1-56975-817-5.

- 宮本他 2007, p. 17

- 郡司聡他編, ed. (2008). "映画で活躍する妖怪四十七士を選ぼう!". 怪. カドカワムック. vol.0025. 角川書店. p. 78. ISBN 978-4-04-885002-5.

- 荒俣宏・小松和彦 (1987). 米沢敬編 (ed.). 妖怪草紙 あやしきものたちの消息. 工作舎. p. 27. ISBN 978-4-87502-139-1.

- 山口 2007, pp. 20-21

- 佐野史郎 (2007). "インタビュー 佐野史郎". In 講談社コミッククリエイト編 (ed.). DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. OfficialFileMagazine. VOL.01. 講談社. p. 29. ISBN 978-4-06-370031-2.

- "知識の宝庫! 目がテン! ライブラリー". 所さんの目がテン!. 日本テレビ. 2010-12-11. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- 宮本幸枝 (2005). 村上健司監修 (ed.). 津々浦々「お化け」生息マップ - 雪女は東京出身? 九州の河童はちょいワル? -. 大人が楽しむ地図帳. 技術評論社. pp. 96頁. ISBN 978-4-7741-2451-3.

- "妖怪人気NO1は一反木綿 鬼太郎は4位". 47NEWS. www.pnjp.jp/ 全国新聞ネット. 2007-03-17. Archived from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- 山口敏太郎・天野ミチヒロ (2007). 決定版! 本当にいる日本・世界の「未知生物」案内. 笠倉出版社. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-4-7730-0364-2.

- 京極夏彦他 (2001). 妖怪馬鹿. 新潮OH!文庫. 新潮社. p. 354. ISBN 978-4-10-290073-4.

- 山口敏太郎 (2007). 山口敏太郎のミステリー・ボックス コレが都市伝説の超決定版!. メディア・クライス. p. 188. ISBN 978-4-778-80334-6.

- 多田克己 (1999). "絵解き 図画百鬼夜行の妖怪". In 郡司聡他編 (ed.). 季刊 怪. カドカワムック. 第7号. 角川書店. p. 281. ISBN 978-4-04-883606-7.

- 大藤時彦他 (1955). 民俗学研究所編 (ed.). 綜合日本民俗語彙. 第4巻. 柳田國男監修. 平凡社. p. 1359. NCID BN05729787.

- 柳田國男編 (1949). 海村生活の研究. 日本民俗学会. p. 319. NCID BN06575033.

- 村上健司編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. p. 297. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- 宮本他 2007, p. 65.

References

- 板垣博之 (2007-08-07). "妖怪のこころ 1". 毎日新聞(朝刊). 毎日新聞社. p. 15.

- 多田克己 (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち. Truth In Fantasy. IV. 新紀元社. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- 水木しげる (1994). 図説 日本妖怪大全. 講談社+α文庫. 講談社. ISBN 978-4-06-256049-8.

- 宮本幸枝・熊谷あづさ (2007). 日本の妖怪の謎と不思議. GAKKEN MOOK. 学習研究社. ISBN 978-4-05-604760-8.

- 山口敏太郎 (2007). 本当にいる日本の「現代妖怪」図鑑. 笠倉出版社. ISBN 978-4-7730-0365-9.