Sōjōbō

Sōjōbō (Japanese: 僧正坊, pronounced [soːd͡ʑoːboː]) is the mythical king of the tengu. In Japanese folklore and mythology, the tengu are legendary creatures thought to inhabit the mountains and forests of Japan. Sōjōbō is a specific type of tengu called daitengu and has the appearance of a yamabushi, a Japanese mountain hermit. Daitengu have a primarily human form with some bird-like features such as wings and claws. The other distinctive physical characteristics of Sōjōbō include his long, white hair and unnaturally long nose.

| |

| Grouping | Legendary creatures |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Tengu |

| Other name(s) | King of the tengu, Kurama tengu, Great tengu |

| Country | Japan |

Sōjōbō is said to live on Mount Kurama. He rules over the other tengu that inhabit Mount Kurama in addition to all the other tengu in Japan. He is extremely powerful, and one legend says he has the strength of 1,000 normal tengu.

Sōjōbō is perhaps best known for the legend of his teaching the warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune (then known by his childhood name Ushiwaka-maru or Shanao) the arts of swordsmanship, tactics, and magic.

Etymology

Most tengu are referred to impersonally (Ashkenazi 56). Sōjōbō is an exception and is one of the tengu that are given personal names and recognised as individual personalities (Ashkenazi 56). The name Sōjōbō originated in a text called Tengu Meigikō, which dates back to the middle of the Edo period in Japan (Knutsen 95).

The name Sōjōbō originates from Sōjōgatani, the valley at Mount Kurama near Kibune Shrine associated with the Shugenja. It is in this valley that Ushiwaka-maru trained with Sōjōbō in legend. Sōjōgatani means Bishop’s valley or Bishop’s vale (Knutsen114; de Benneville 273). The name of this valley is derived from the ascetic Sōjō Ichiyen (de Benneville 273).

In Japanese, the name Sōjōbō is composed of three kanji: 僧,正,坊. The first two characters of Sōjōbō’s name (僧正, sōjō) mean 'Buddhist high priest' in Japanese. The final kanji (坊, bō) of the name, M.W. de Visser says, also means “Buddhist priest” but is also commonly used to mean yamabushi (82).

The yamabushi (山伏, 'those who lie down in the mountains') are ascetics from the Shugendō tradition (Buswell et al. 1019). Shugendō (修驗道, 'way of cultivating supernatural power') incorporates elements of many religious traditions, including Buddhism (Buswell et al. 812). Both tengu and yamabushi had a reputation for dwelling in the mountains. Yves Bonnefoy suggests that this contributed to the folk belief that yamabushi and tengu were identical or at least closely connected (286).

Other names

Sōjōbō is also referred to by other names and titles that function as names. Sōjōbō is sometimes called the Kurama tengu (Ashkenazi 271,56). This name references Sōjōbō’s mountain home, Mount Kurama. Ronald Knutsen refers to Sōjōbō by the title of Tengu-san (114). Sōjōbō is also named by references to his title as the king of the tengu (Knutsen 114; Davis 41; “Or 13839”). For example, James de Benneville refers to Sōjōbō using the term goblin-king (273). Similarly, Catherina Blomberg says that the titles “Dai Tengu (Great Tengu) or Tengu Sama (Lord Tengu)” are used to name Sōjōbō (35). Sometimes, Sōjōbō is named using both a title and a reference to Mount Kurama. The Noh play Kurama-Tengu, for example, features a character named Great Tengu of Mount Kurama (“Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”).

Mythology

those arts of war

that for many months and years

upon the Mountain of Kurama

I have rehearsed— Miyamasu, Eboshi-ori (qtd. in Knutsen 114)

Sōjōbō is known for his relationship with the Japanese warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune in legend (Cali and Dougill 125). After Yoshitsune’s father was killed in a battle with the Taira clan, the young Yoshitsune was sent to a temple on Mount Kurama (Davis 41; Ashkenazi 97). On Mount Kurama, Yoshitsune met Sōjōbō and was trained by him in martial arts (Ashkenazi 97). Yoshitsune became a highly skilled warrior as a result of Sōjōbō’s training (Davis 42). For example, in the war epic Heiji monogatari (The Tale of Heiji) it is said that the training young Yoshitsune received “was the reason why he could run and jump beyond the limits of human power” (qtd. in de Visser 47).

Portrayal

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, de Visser says that tengu were thought to be “a mountain demon” that caused trouble in the human world (38). In stories from this period, tengu were portrayed as enemies of Buddhism (de Visser 43). Later, tengu were no longer seen as enemies of Buddhism specifically, but were portrayed as wanting to “throw the whole word into disorder” (de Visser 67). According to de Visser, the reason Sōjōbō trains Yoshitsune in martial arts is to start a war (48).

In the Gikeiki, a text concerning the life of Yoshitsune, Sōjōgatani or Bishop's valley is described as being the location of a once popular temple that is now deserted except for tengu (qtd. in de Visser 48). According to the text, when evening approaches “there is a loud crying of spirits” and whoever visits the valley is seized by the tengu and tortured (qtd. in de Visser 48). A similar phenomenon is called kamikakushi. Kamikakushi involves the kidnapping of human beings by a supernatural entity, such as a tengu (Foster 135). It involves the disappearance of a child, usually a boy, followed by their return at a new and strange location and in a seemingly altered state (Foster 135). Cases of kamikakushi can be caused by any yōkai, but tengu are often said to be involved (Foster 137). Michael Foster says that the legend of the young Yoshitsune’s interaction with the tengu “fits the pattern” of a kamikakushi kidnapping (Foster 137).

In the fourteenth century, de Visser says, there is a change from all tengu being portrayed as bad to distinctions made “between good and bad tengu” (93). Foster says that in variations of the legend of Sōjōbō and the young Yoshitsune, the tengu are portrayed as benevolent and helpful as they attempt to help the young Yoshitsune defeat the clan who killed his father (Foster 135).

Foster quotes dialogue from a work called Miraiki (Chronicle of the Future) to demonstrate the idea of the tengu being portrayed in a more benevolent way. After the subordinate tengu see the young Yoshitsune practising near the temple on Mount Kurama, they explain that their prideful ways prevented them from becoming Buddhas and instead caused them to become tengu (Foster 134). Then they say:

But even though this pride caused us to fall into this path, there is no reason we should not know pity. So let us help Ushiwaka, teach him the method of the tengu so he can attack his father’s enemy (qtd. in Foster 134).

The portrayal of the tengu, and Sōjōbō specifically, as sympathetic to the young Yoshitsune and his desire to avenge his father, is also shown in the Noh play Kurama-tengu (“Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”). In the play, the Great Tengu represents the figure of Sōjōbō. The Great Tengu says he his impressed with the Ushiwakamaru character, the young Yoshitsune, for his respectfulness and admirable intentions. Not only does he help Ushiwakamaru by training him to become a great warrior and defeat his enemies, he also promises to protect him and support him in future battles.

Classification

.jpg)

Sōjōbō is a tengu, which are a type of nonhuman creature in Japanese folklore and mythology with supernatural characteristics and abilities (Ashkenazi 56). Tengu are also considered well-known example of yōkai (Foster 130). Yōkai is a term that can describe a range of different supernatural beings. According to Foster, a yōkai can be characterised in a number of ways, such as “… a weird or mysterious creature, a monster or fantastic being, a spirit or a sprit” (24).

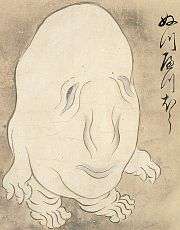

There are two main sub-categories or types of tengu (Foster 131). First, there are tengu with the primary form of a bird and second there are tengu that have the primary form of a human. Tengu of the first sub-category are generally called kotengu but can also be called karasu tengu or shōtengu (Foster 131,135; Knutsen 10). The second sub-category of tengu is called daitengu or “long-nosed tengu” (Knutsen 10). As he is described as having a primarily human form, Sōjōbō belongs to the sub-category daitengu.

Daitengu

The daitengu or long nosed tengu represent a later stage in the development of the concept of tengu in Japan. According to de Visser, tengu were first in the form of a bird, then had a human form with the head of a bird, and finally the bird beak became a long nose (44). Similarly, Basil Hall Chamberlain says that the beak of the tengu “becomes a large and enormously long human nose, and the whole creature is conceived as human” (443). There is no mention of the tengu having long noses in Japanese tales until after the second half of the fourteenth century (de Visser 44). While the kotengu or bird type of tengu came first, the daitengu with the long human nose is more common in modern Japanese culture (Foster 131). Sōjōbō is one of the “eight great dai-tengu” and, of these, one of the three that are most well-known (Knutsen 95).

Characteristics

Physical appearance

As a daitengu, Sōjōbō has a primarily human form. Frederick Hadland Davis describes Sōjōbō as having both “bird-like claws, and feathered wings” and “a long red nose and enormous glaring eyes” (Davis 41). Similarly, de Visser says Sōjōbō has “sparkling eyes and a big nose” (95). Sōjōbō is also described as having a long white beard (Ashkenazi 271). Daitengu are described as being larger in overall size than kotengu (Knutsen 10). For example, in one legend Sōjōbō appears to be a giant from the perspective of a human (Davis 41).

One characteristic that both types of tengu share is their style of dress. Tengu are depicted wearing religious clothing and accessories, especially the clothing and accessories of the yamabushi (Foster 131; Blomberg 35). As such, Sōjōbō is often described or depicted with these items and wearing these clothes. The dress of the yamabushi includes formal robes, square-toed shoes, a sword, a scroll, a fan, and a distinctive headdress (Knutsen 128; “Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”). The distinctive headdress worn by yamabushi is called a tokin. A common style of tokin, worn from the start of the Edo period, is a small hat that resembles a black box (Absolon 98). Sōjōbō carries a fan made from seven feathers as a sign of his position at the top of tengu society (Griffis 113). Bonnefoy says that the feather fan carried by tengu may signify the original bird-like features of the tengu (286). Similarly, Davis says that in the development of the concept of tengu from bird-like to more human-like , “nothing bird-like” was left except for “the fan of feathers with which it fans itself” (352).

Supernatural abilities

Another characteristic that Sōjōbō shares with yamabushi is a reputation for having supernatural abilities. Yamabushi often performed various practises in the mountains to try an attain supernatural abilities (Bonnefoy 286). According to folk belief, yamabushi had the abilities of flight and invisibility (Knusten 113). Tengu were thought to be able to spiritually possess human beings, similar to foxes (Bonnefoy 285). Other abilities attributed to tengu include invisibility, shapeshifting, flight, and the ability to tell the future (Bonnefoy 285, 287). Sōjōbō is portrayed as having a reputation for being more powerful than other tengu or being a “match for a thousand” (Kimbrough 4).

Roles

Mount Kurama chieftain

The daitengu subcategory of tengu is superior to the kotengu in rank (Knutsen 10). Foster says that the different types of tengu were often depicted as being in a hierarchical relationship to one another, with the daitengu “flanked by a posse” of the kotengu who are “portrayed as lieutenants” to the daitengu (Foster 135). The higher rank of the daitengu is also shown by the hierarchical structure on the tengu mountains.

In general, tengu of both types are thought to inhabit mountainous areas in Japan (Blomberg 35). Some individual daitengu are linked with specific mountains in Japan and are considered to be the chieftains of the other tengu on that mountain (Knutsen 95; Blomberg 35). The mountain that Sōjōbō is said to inhabit is Mount Kurama. According to Knutsen, Mount Kurama is “associated in the popular mind with the tengu” (113). Mount Kurama is located north of the city of Kyōto in Japan. On Mount Kurama there is a famous shrine and temple called Kuramadera, which dates back to 770AD (Cali and Dougill 124). The mountain has connections to the history of both reiki and aikido (Cali and Dougill 124). Mount Kurama is known as a “new-age power spot” in modern times (Cali and Dougill 125).

Sōjōbō is considered to be the chieftain of Mount Kurama (Blomberg 35). Blomberg describes Sōjōbō as having “retainers” who “have the form of a karasu tengu” (35). An example of the hierarchy of the two sub-categories of tengu is exhibited in the Noh play Kurama-Tengu. In the play, there are tengu characters who are described as menial and are given orders by Sōjōbō or the Great Tengu character (“Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”).

King of the tengu

.jpg)

In addition to role of chieftain of Mount Kurama, Sōjōbō is considered to be the chieftain or king of all the other tengu mountains in Japan (Blomberg 35). Sōjōbō’s role as king of the tengu is demonstrated in the Noh play Kurama-Tengu. In the play, the Great Tengu lists his large number of tengu servants, which are not just tengu from Mount Kurama but tengu from other areas as well (“Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”). This demonstrates his authority over both the tengu on Mount Kurama and all the other tengu in Japan. This authority is also shown in a story called The Palace of the Tengu. In the story, the figure of Sōjōbō is called Great Tengu. He orders one of his tengu servants to send a message to summon the tengu chieftains of other mountains on his behalf (Kimbrough and Shirane). These tengu chieftains include “Tarōbō of Mount Atago, Jirōbō of Mount Hira, Saburōbō of Mount Kōya, Shirōbo of Mount Nachi, and Buzenbō of Mount Kannokura” (Kimbrough and Shirane).

Sōjōbō is specifically associated with a place on Mount Kurama called Sōjōgatani or Bishop’s valley (Knutsen 114; de Benneville 273). According to de Benneville, this area was thought to be “the haunt of tengu, even … the seat of the court of their goblin-king” (de Benneville 273). Similarly, de Visser says that some tengu live in “brilliant palaces” and Sōjōbō or the “Great Tengu” was “the Lord of such a palace” (95). Sōjōbō’s tengu palace features in the story The Palace of the Tengu. A character in this story, Minamoto no Yoshitsune, reaches the tengu palace by starting at the bottom of the slope of the temple on Mount Kurama, climbing a path up the mountainside until he reaches coloured walls that lead him to the gates of the palace (Kimbrough and Shirane). He finds the palace to be very large, elaborate, and decorated with different jewels (Kimbrough and Shirane). According to the story, the palace contains “hundreds of tengu” (Kimbrough and Shirane).

Appearances

In performing arts

The Noh play Kurama-Tengu features an interpretation of the legend about Sōjōbō and Yoshitsune. Noh (能, nō, ‘skills or artistry’) is a genre of traditional Japanese theatre (Kagaya and Hiroko 24; Salz 51). Shinko Kagaya and Miura Hiroko say Noh is comparable to opera because of its focus on dance and music (24).

In Kurama-Tengu, Sōjōbō is initially disguised as a mountain priest and befriends the young Yoshitsune (called Ushiwakamaru at this age) at a celebration of the cherry blossoms on Mount Kurama. Then the following exchange between the two characters occurs:

USHIWAKAMURU. By the way, you, the gentleman who comforts me, who

are you? Please give me your name.

MOUNTAIN PRIEST. There is nothing to hide now, I am the Great Tengu of

Mount Kurama, who has lived in this mountain for hundreds of years.

After his true identity is revealed, the Great Tengu says he will “hand down the secret of the art of war” to Ushiwakamaru (“Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”). The Great Tengu instructs the menial tengu to practice with Ushiwakamaru. Ushiwakamaru then becomes extremely skilled, as demonstrated by the words of the reciters who say that “even the monsters in the heavens and the demons in the underworld will be unable to beat his elegance with braveness” (“Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama)”). The play ends with the Great Tengu predicting that Ushiwakamaru will defeat his enemies and avenge his father. He then promises to protect Ushiwakamaru before disappearing into the trees of Mount Kurama.

The legend of Yoshitsune learning martial arts from the tengu is also featured in another genre of Japanese drama called kōwakamai. The main element of kōwakamai is performance, but the texts associated with the performances are also significant to the genre (Kimbrough, Cambridge History of Japanese Literature 362). The kōwakamai work featuring the legend is called Miraiki (Chronicle of the Future). This work has a similar plot to the literary work Tengu no dairi (The Palace of the Tengu) (Kimbrough, Cambridge History of Japanese Literature 359).

In literary arts

An example from the literary arts of the legend of Sōjōbō and Yoshitsune is the otogi-zōshi story called Tengu no dairi (The Palace of the Tengu). Otogi-zōshi is a genre of Japanese fiction that was prominent in the fourteenth century and up to seventeenth century (Kimbrough and Shirane). Sōjōbō also independently features in an otogi-zōshi story called The Tale of the Handcart Priest.

In Tengu no dairi (The Palace of the Tengu), a young Yoshitsune seeks out and visits the palace of the tengu. He meets the Great Tengu and his wife, who tell him that his father “has been reborn as Dainichi Buddha in the Pure Land of Amida” (Kimbrough, Cambridge History of Japanese Literature 358). The story then covers the supernatural journey of the Great Tengu and the young Yoshitsune through the “six planes of karmic transmigration” to visit Yoshitsune’s father in the Pure Land (Kimbrough, Cambridge History of Japanese Literature 358).

Sōjōbō is not the protagonist of the story The Tale of the Handcart Priest but is mentioned when a group of tengu notice his absence from their gathering. They were gathering to conspire against the character the Handcart Priest and were in need of Sōjōbō’s help. A messenger is sent to Sōjōbō to ask for his help, and he tells the messenger that he doesn't want to take part because he has been nearly fatally wounded by the Handcart Priest and “may not survive” (Kimbrough 5). The other tengu say that they will never succeed without the aid of Sōjōbō and that the Handcart Priest must be remarkable if he was able to wound “the likes of our Sōjōbō” (Kimbrough 5).

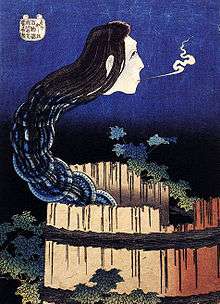

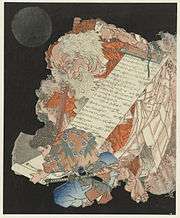

In visual arts

The legendary relationship between Sōjōbō as instructor and the young Yoshitsune as student serves as the basis of many Japanese woodblock prints. Many of these works were created by artists known for their work in the ukiyo-e genre. Some of these artists include Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Utagawa Hiroshige, Kawanabe Kyōsai, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Kunisada, and Keisai Eisen.

Related figures

.jpg)

.png)

Related figures to Sōjōbō include the other two famous tengu, Zegaibō of China and Tarōbō of Mount Atago (Kimbrough, Ashgate Encyclopedia 530). Like Sōjōbō, these tengu are daitengu, chieftains of a tengu mountain, and appear in different forms of Japanese art. Kimbrough says that in one version of the Heike monogatari, the tengu Tarōbō is described as the greatest tengu in Japan (Ashgate Encyclopedia 531). In the text Gempei Seisuiki, Tarōbō is described as the first of the great tengu (qtd. in de Visser 53).

Sōjōbō is also depicted with a similar appearance to other types of supernatural entities. After looking at a drawing of Yoshitsune with a long-nosed tengu, Osman Edwards says that the tengu “has many characteristics in common with the Scandinavian trold” (154). In Scandinavian folklore, the troll is a legendary monster that, like the tengu, dwells in mountains and forests (Bann 544). Secondly, Sōjōbō and daitengu in general are depicted in a similar way to a kami or Shinto deity called Sarutahiko (Cali and Dougill 125). Ashkenazi says descriptions of Sarutahiko present him as being very tall, having an extremely long nose, and with "mirror-like eyes" that "shone cherry-red from inner flames" (245).

Modern legacy

One modern legacy of Sōjōbō is his representation in Japanese festivals. According to F. Brinkley, entities from the “region of allegory” are honoured at these festivals alongside deities (3). At some festivals, decorated shrines devoted to a particular deity or subject are mounted on a wooden cart called a dashi and are carried down the streets in a procession as part of the festival’s celebrations (Brinkley 3). At the festival of Sanno in Tokyo, there is a dashi dedicated to Ushiwaka and Sōjōbō (5). Brinkley says that it was common for the people attending to festival to know the history surrounding each dashi and its subject (6).

The influence of Sōjōbō is also present in popular culture. Tengu have become a common subject in different forms Japanese media including film, video games, manga, and anime (Kimbrough Ashgate Encyclopedia 531). One example is the film Kurama tengu, which shares a name with one of Sōjōbō’s other names.

Works Cited

- Absolon, Trevor, and David Thatcher. The Watanabe Art Museum Samurai Armour Collection: Volume I ~ Kabuto & Mengu. Toraba, 2011. Google Books, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=8APyY3eIONcC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Ashkenazi, Michael. Handbook of Japanese Mythology. ABC-CLIO, 2003. Google Books, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=gqs-y9R2AekC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Bann, Jenny. "Troll." The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters, edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315612690

- Blomberg, Catharina. The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan. Routledge, 1994.

- Bonnefoy, Yves, and Wendy Doniger. Asian Mythologies. U of Chicago P, 1993.

- Brinkley, F. Japan, Its History, Arts and Literature. J.B. Millet, c1901-02. HathiTrust Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433082124169

- Buswell, Robert E., et al. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton UP, 2017.

- Cali, Joseph, and John Dougill, Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion. U of Hawai’i P, 2013.

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall. Things Japanese. Kelly & Walsh, 1905. Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Things_Japanese

- Davis, Frederick Hadland. Myths & Legends of Japan. T.Y. Crowell co, 1912. HathiTrust Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b233536

- de Benneville, James Seguin. Saito Musashi-Bo Benkei: Tales of the Wars of the Gempei, Being the Story of the Lives and Adventures of Iyo-No-Kami Minamoto Kuro Yoshitsune and Saito Musashi-Bo Benkei. J.S. De Benneville, 1910. Internet Archive Books, https://archive.org/stream/saitomusashibobe01debe/saitomusashibobe01debe

- de Visser, Marinus Willem. The Tengu. Asiatic Society of Japan, 1908. HathiTrust Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924066003868?urlappend=%3Bseq=769

- Edwards, Osman. Japanese Plays and Playfellows, John Lane, 1901. Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Japanese_Plays_and_Playfellows&oldid=7652212

- Foster, Michael Dylan. The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese folklore. U of California P, 2015.

- Griffis, William Elliot. Japanese Fairy World: Stories from the Wonder-Lore of Japan. J. H. Barhyte, 1880. HathiTrust Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b292831

- Kagaya, Shinko, and Miura Hiroko. “Noh and Muromachi Culture.” A History of Japanese Theatre, edited by Jonah Salz, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 24–61.

- Kimbrough, R. Keller. “The Tale of the Handcart Priest.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, 2012, pp. 1-7. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1285490921

- ---. “Late Medieval Popular Fiction and Narrated Genres: Otogizōshi, Kōwakamai, Sekkyō, and Ko-Jōruri.” The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature, edited by Haruo Shirane et al., Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139245869

- ---.“Tengu.” The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters, edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315612690

- Kimbrough, Keller, and Haruo Shirane, editors. Monsters, Animals, and Other Worlds: A Collection of Short Medieval Japanese Tales. Columbia UP, 2018.

- Knutsen, Ronald. Tengu: The Shamanic and Esoteric Origins of the Japanese Martial Arts. Global Oriental, 2011.

- “Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama).” the-Noh.com, https://www.the-noh.com/en/plays/data/program_025.html

- "Or 13839." British Library, https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Or_13839

- Salz, Jonah. "Traditional Japanese theatre." Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre, edited by Siyuan Liu, Routledge, 2016. Routledge Handbooks Online, doi:10.4324/9781315641058.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sōjōbō. |

- Sōjōbō Entry from an online database featuring information and original illustrations of the Japanese legendary creatures known as yōkai.

- Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama): PhotoStory Photographs from a performance of the Noh play Kurama-tengu.

- Tengu Part of a digital exhibition called Yōkai Senjafuda by the University of Oregon.

- Ushiwakamaru and the Giant Tengu Photograph of a float depicting Sōjōbō and Ushiwakamaru at a traditional Japanese festival called the Aomori Nebuta Matsuri.