Chalcedon

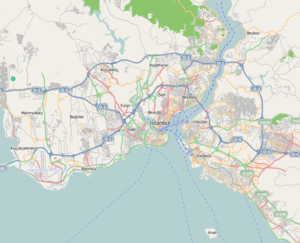

Chalcedon (/kælˈsiːdən/ or /ˈkælsɪdɒn/;[1] Greek: Χαλκηδών, sometimes transliterated as Chalkedon) was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the city of Istanbul named Kadıköy. The name Chalcedon is a variant of Calchedon, found on all the coins of the town as well as in manuscripts of Herodotus's Histories, Xenophon's Hellenica, Arrian's Anabasis, and other works. Except for a tower, almost no above-ground vestiges of the ancient city survive in Kadıköy today; artifacts uncovered at Altıyol and other excavation sites are on display at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Chalcedon Χαλκηδών | |

|---|---|

Town | |

The small church of St Euphemia that serves as the Greek Orthodox cathedral of the Metropolitan Diocese | |

| Etymology: Carthage | |

Bithynia as a province of the Roman Empire, 120 AD | |

| Coordinates: 40°59′04″N 29°01′38″E | |

| Country | Bithynia |

The site of Chalcedon is located on a small peninsula on the north coast of the Sea of Marmara, near the mouth of the Bosphorus. A stream, called the Chalcis or Chalcedon in antiquity[2] and now known as the Kurbağalıdere (Turkish: stream with frogs), flows into Fenerbahçe Bay. There Greek colonists from Megara in Attica founded the settlement of Chalcedon in 685 BC, some seventeen years before Byzantium.

The Greek name of the ancient town is from its Phoenician name qart-ħadaʃt, meaning "New Town", whence Karkhēd(ōn),[3] as similarly is the name of Carthage. The mineral chalcedony is named after the city.[4]

Prehistory

The mound of Fikirtepe has yielded remains dating to the Chalcolithic period (5500-3500 BC) and attest to a continuous settlement since prehistoric times. Phoenicians were active traders in this area.

Pliny states that Chalcedon was first named Procerastis, a name which may be derived from a point of land near it: then it was named Colpusa, from the harbour probably; and finally Caecorum Oppidum, or the town of the blind.[5]

Megarian colony

Chalcedon originated as a Megarian colony in 685 BC. The colonists from Megara settled on a site that was viewed in antiquity as so obviously inferior to that visible on the opposite shore of the Bosphorus (with its small settlements of Lygos and Semistra on Seraglio Point), that the 6th-century BC Persian general Megabazus allegedly remarked that Chalcedon's founders must have been blind.[6] Indeed, Strabo and Pliny relate that the oracle of Apollo told the Athenians and Megarians who founded Byzantium in 657 BC to build their city "opposite to the blind", and that they interpreted "the blind" to mean Chalcedon, the "City of the Blind".[7][8]

Nevertheless, trade thrived in Chalcedon; the town flourished and built many temples, including one to Apollo, which had an oracle. Chalcedonia, the territory dependent upon Chalcedon,[9] stretched up the Anatolian shore of the Bosphorus at least as far as the temple of Zeus Urius, now the site of Yoros Castle, and may have included the north shore of the Bay of Astacus which extends towards Nicomedia. Important villages in Chalcedonia included Chrysopolis[10] (the modern Üsküdar) and Panteicheion (Pendik). Strabo notes that "a little above the sea" in Chalcedonia lies "the fountain Azaritia, which contains small crocodiles".[11]

In its early history Chalcedon shared the fortunes of Byzantium. Later, the 6th-century BC Persian satrap Otanes captured it. The city vacillated for a long while between the Lacedaemonian and the Athenian interests. Darius the Great's bridge of boats, built in 512 BC for his Scythian campaign, extended from Chalcedonia to Thrace. Chalcedon formed a part of the kingdom of Bithynia, whose king Nicomedes willed Bithynia to the Romans upon his death in 74 BC.

Roman city

The city was partly destroyed by Mithridates. The governor of Bithynia, Cotta, had fled to Chalcedon for safety along with thousands of other Romans. Three thousand of them were killed, sixty ships captured, and four ships destroyed in Mithridates' assault on the city.[12]

During the Empire, Chalcedon recovered, and was given the status of a free city. It fell under the repeated attacks of the barbarian hordes who crossed over after having ravaged Byzantium, including some referred to as Scythians who attacked during the reign of Valerian and Gallienus in the mid 3rd century.[13]

Byzantine and Ottoman suburbs

Chalcedon suffered somewhat from its proximity to the new imperial capital at Constantinople. First the Byzantines and later the Ottoman Turks used it as a quarry for building materials for Constantinople's monumental structures.[14] Chalcedon also fell repeatedly to armies attacking Constantinople from the east.

In 361 AD it was the location of the Chalcedon tribunal, where Julian the Apostate brought his enemies to trial.

In 451 AD an ecumenical council of Christian leaders convened here. See below for this Council of Chalcedon.

The general Belisarius probably spent his years of retirement on his estate of Rufinianae in Chalcedonia.

Beginning in 616 and for at least a decade thereafter, Chalcedon furnished an encampment to the Persians under Chosroes II[15] (cf. Siege of Constantinople (626)). It later fell for a time to the Arabs under Yazid (cf. Siege of Constantinople (674)).

Chalcedon was badly damaged during the Fourth Crusade (1204). It came definitively under Ottoman rule under Orhan Gazi a century before the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople.

Ecclesiastical history

Chalcedon was an episcopal see at an early date and several Christian martyrs are associated with Chalcedon:

- The virgin St. Euphemia and her companions in the early 4th century; the cathedral of Chalcedon was consecrated to her.

- St. Sabel the Persian and his companions.

It was the site of various ecclesiastical councils. The Fourth Ecumenical Council, known as 'the' Council of Chalcedon, was convened in 451 and defined the human and divine natures of Jesus, which provoked the schism with the churches composing Oriental Orthodoxy.

After the council, Chalcedon became a metropolitan see, but without suffragans. There is a list of its bishops in Le Quien,[16] completed by Anthimus Alexoudes,[17] revised for the early period by Pargoire.[18] Among others are:[19]

- St. Adrian, a martyr;

- St. John, Sts. Cosmas and Nicetas, during the Iconoclastic period;

- Maris, the Arian;

- Heraclianus, who wrote against the Manichaeans and the Monophysites;

- Leo, persecuted by Alexius I Comnenus.

Greek and Catholic successions

The Greek Orthodox Metropolitan of Chalcedon holds senior rank (currently third position) within the Greek Orthodox patriarchal synod of Constantinople. The incumbent is Metropolitan Athanasios Papas. The cathedral is that of St. Euphemia.

After the Great Schism, the Latin Church retained Chalcedon as a titular see with archiepiscopal rank,[20] with known incumbents since 1356. Among the titular bishops named to this see were William Bishop (1623–1624) and Richard Smith (1624–1632), who were appointed vicars apostolic for the pastoral care of Catholics in England at a time when that country had no Catholic diocesan bishops. Such appointments ceased after the Second Vatican Council and the titular see has not been assigned since 1967.[21]

Chalcedon has also been a titular archbishopric for two Eastern Catholic church dioceses:

- Syrian (Antiochian Rite, established in 1922; vacant since 1958)

- Armenian Catholic (Armenian Rite, established 1951, after two incumbents, suppressed in 1956).

Notable people

- Euphemia (3rd century AD), Christian saint and martyr, patron saint of Kalkhedon

- Boethus (2nd century BC), Greek sculptor

- Herophilos (2nd century BC), Greek physician

- Phaleas of Chalcedon (4th century BC), Greek statesman

- Thrasymachus (5th century BC), Greek sophist

- Xenocrates (4th century BC), Greek philosopher

See also

- List of ancient Greek cities

- List of traditional Greek place names

- Chalkidona, Greece

References

- "Chalcedon". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. (accessed: September 21, 2008).

- William Smith, LLD, ed. (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. "Chalcedon".

- Harper, Douglas. "Chalcedony". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- Erika Zwierlein-Diehl: Antike Gemmen und ihr Nachleben. Berlin (Verlag Walter de Gruyter) 2007, S. 307 (online)

- Pliny. Nat. 5.43

- Herodotus. Histories. 4.144.

- Strabo (p. 320).

- Pliny. Nat. 9.15

- Herodotus. Histories. 4.85.)

- Xenophon, Xen. Anab. 6.6, 38-Z1.

- Strabo 1.597.

- Appian. Mithrid. 71; Plut. Luc. 8.

- Zosimus 1.34.

- Ammian. 31.1, and the notes of Valesius.

- Gibbon. Decline, &c. 100.46.

- Michel Le Quien, Oriens christianus, I, 599.

- In Anatolikos Aster XXX, 108.

- In Échos d'Orient III, 85, 204; IV, 21, 104.

- Sophrone Pétridès, "Chalcedon" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1908)

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 855

- Chalcedon (Titular See)

![]()