Jubilee Clock Tower, Churchill

The Jubilee Clock Tower, striking clock, and drinking fountain, is a Grade II listed building in the village of Churchill in North Somerset, built to commemorate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897. It stands on a plot between Dinghurst Road and Front Street, and is a prominent landmark at the entrance to the village. Designed by Joseph Foster Wood of Foster & Wood, Bristol, the tower is made of local stone and is of perpendicular Gothic style.

| Jubilee Clock Tower | |

|---|---|

Jubilee Clock Tower | |

| Type | Clock tower |

| Location | Churchill, North Somerset, England |

| Coordinates | 51.333833°N 2.799260°W |

| Height | 12 metres (40 feet) |

| Founded | 1897 |

| Founder | Sidney Hill |

| Built | 1898 |

| Built for | Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee |

| Restored | 1976–1977 |

| Architect | Joseph Foster Wood FRIBA of Foster & Wood, Bristol |

| Architectural style(s) | Free-form Gothic style |

| Governing body | Churchill Parish Council |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name: Jubilee Clock Tower and attached walls and railings | |

| Designated | 19 January 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1129198 |

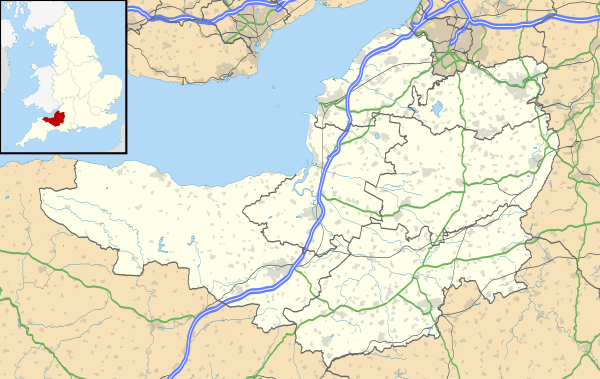

Location of Jubilee Clock Tower in Somerset | |

The tower has a cast iron clock face on each of its four sides with one mechanism driving the clock hands. The escapement and clockwork mechanism is still in use and was supplied by J. B. Joyce & Co in 1898. The bell chimes on the hour and quarter-hour and the mechanism is wound every three days by volunteers. Responsibility for maintenance of the clock tower transferred to the parish council after the original trust could no longer afford to maintain it. The whole structure, tower, walls, and railings, was designated as a Grade II listed building on 19 January 1987, nearly 90 years after the tower was built.

History

Inception

In 1897, Sidney Hill, a local businessman and benefactor, purchased the old turnpike house, near the Nelson Arms pub in Churchill, and also a house and plot of land between Dinghurst Road and Front Street, near the entrance to Churchill village. Both sites were in a state of disrepair and were unsightly.[1] Hill planned to clear the old buildings and debris, plant ornamental shrubs, and enclose the plots with iron railings; similar in design to the then plantation in front of the nearby Wesleyan Methodist chapel and schoolroom that Hill had built in Front Street, Churchill, in 1881.[2] Furthermore, his intention was to build a clock tower on the Dinghurst Road and Front Street site to mark Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897.[1]

Design

Sidney Hill engaged Joseph Foster Wood FRIBA, of Foster & Wood, Bristol, to design the clock tower.[3][lower-alpha 1] Hill had engaged the same firm of architects to design the Wesleyan Methodist chapel and schoolroom.[2] Foster & Wood was a busy architectural practice in Victorian Bristol and many landmark Bristol buildings were designed by them, including Fosters Almshouse (1861), Colston Hall (1864), the Grand Hotel on Broad Street (1864–1869), Bristol Grammar School (1875), as well as a large number of Wesleyan chapels throughout the city.[5]

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Architectural elements[6][lower-alpha 2]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Build

The tower was built by the end of 1897, and the bell and clock mechanism were installed the following year by J. B. Joyce & Co.[8] On 31 July 1901, Sidney Hill gifted the clock tower, along with the old Wesleyan schoolroom next to the tower, to the Churchill Memorial Chapel and School Trust.[9] Graham Clifford Awdry FRIBA, Joseph Foster Wood's former business partner, wrote in Wood's obituary, "A charming memorial tower at Churchill, Somerset, is a good specimen of his originality".[3]

Restoration

By March 1974, the wall surrounding the tower was crumbling, and the tower stonework required pointing and cleaning.[10] The clock's winding mechanism was also in a poor state of repair and it would have cost a thousand pounds to mechanise it. The Churchill Memorial Chapel and Schools Endowment Trust, the trust in charge of the tower, had an annual income of £500 and was paid £12 pounds per year by the parish council to maintain the tower. The trust had asked for more help from the parish council, as they had concluded that it was not possible to maintain the tower and the other church properties for which they were responsible.[11]

It was recognised that the long-term future of the tower lay either with listing the tower as an historic monument or that the parish council take over the maintenance of the tower.[12] By September 1976, the trust had applied to the Charity Commissioner to have its responsibilities transferred to the parish council.[13] In the same month, John Edgar Howard Smith, the managing director of Smith of Derby Group and the owners of J. B. Joyce & Co, wrote to the parish council offering to carry out a free survey of the clock, although at the time of Smith's letter, the trust had recently refurbished and renovated the mechanism at a cost of £211.[8]

In 1977, for the Queen's Silver Jubilee, the tower was cleaned by Arthur Raymond Millard ("Ray Millard") BEM, former chairman of Churchill Parish Council, and a team of volunteers.[14] In 1979, a plaque was affixed to the west side of the tower to commemorate the work of Millard and the volunteers.[15]

Features

The tower has a cast iron clock face on each of its four sides, with Roman numerals indicating 12 hours on each face. The clocks are attached to a square tower that has buttresses to the first floor. One mechanism drives the faces on all sides of the of the tower. The second floor holds the clock mechanism and bell. A drinking fountain, with a cast iron tap and water pump fittings, is built into a niche on the east side of the tower.[6][lower-alpha 3]

The inscription on the string course below the bell floor reads:

- West "JUNE 20 1897 THIS TOWER"

- South "& CLOCK WAS ERECTED BY SIDNEY HILL JP OF LANGFORD HOUSE IN"

- East "THIS PARISH TO COMMEMORATE THE SIXTY YEARS OF THE BENEFICENT"

- North "REIGN OF HER MOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA"

References

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 17 April 1897, p. 8.

- Weston Mercury 14 May 1881, p. 2.

- Royal Institute of British Architects 1917, p. 120.

- Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 25 September 1937, p. 15.

- Foster & Wood 1870.

- Historic England & 1129198.

- Conway & Roenisch 2015, p. 115.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 7 October 1976, p. 3.

- Deed of Gift 1901.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 22 March 1974, p. 1.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 22 March 1974, p. 3; Cheddar Valley Gazette 7 October 1976, p. 3.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 22 March 1974, p. 3.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 30 September 1976, p. 3.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 10 March 1977, p. 3.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 5 July 1979, p. 1.

- Churchill Parish Council 2019.

- The Tower 2015, p. 3.

- Archer 2009, p. 240.

Footnotes

- Joseph Foster Wood Hill was the son and nephew of the founders of Foster & Wood.[4]

- Ashlar consists of cut stone blocks that are squared so that smooth sides make fine joints so that level courses are possible. It is often used to face walls built of rubblestone, brick or concrete.[7]

- The fountain was intended to provide drinking water "for man and beast".[18]

Bibliography

Books and journals

- Archer, Peter (2009). "25. Simon Sidney Hill". In Fryer, Jo; Gowar, John; et al. (eds.). Mores Stories From Langford: History and tales of houses and families. Lower Langford: Langford History Group. pp. 233–246. ISBN 978-0-9562253-1-3. OCLC 743449641.

- Conway, Hazel; Roenisch, Rowan (2015). Understanding architecture: An introduction to architecture and architectural history. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-97319-6. OCLC 906184770.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (March 1917). "Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Joseph Foster Wood: Memoir". Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Third. Royal Institute of British Architects. 24: 120. ISSN 0035-8932. OCLC 1764591. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

Newspapers

- "Churchill. The New Wesleyan Memorial Chapel". Weston Mercury. 14 May 1881. p. 2. OCLC 751662463. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Churchill. The Diamond Jubilee". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 17 April 1897. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Married Three Weeks. Death of Mr. G. Awdry, of Bathford". Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. 25 September 1937. p. 15. OCLC 1016318847. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Victoriana Landmark to be Saved". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 22 March 1974. pp. 1, 3. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Dilapidated old clock could be a village asset". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 30 September 1976. p. 3. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "Councillors to tidy up round Churchill clock". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 7 October 1976. p. 3. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "The Jubilee clean up for Jubilee Clock". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 10 March 1977. p. 3. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Plaque for Churchill's clock tower". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 5 July 1979. p. 1. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "The Tower newsletter Issue 34. From the committees" (PDF). Churchill Parish Council. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

Websites

- "Committees". Churchill Parish Council. 26 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Historic England. "Jubilee Clock Tower and attached Walls and Railing (1129198)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

Archives

- Record relating to Foster & Wood, Architects. Bristol: Bristol Archives. 1870. 45855. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Copy Deed of Gift. Churchill Memorial Chapel and School Trust: Sidney Hill of Langford House, Langford, Somerset to trustees, of schoolroom, clock tower and land. 40314: Records of the West Mendip Methodist Circuit and associated circuits and churches. Bristol: Bristol Archives. 31 July 1901. 40314/Ch/8i. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Further reading

- Hodges, Michael A. (1996). Churchill: A Brief History of the area of the Civil Parish (Revised 13 September 1996 ed.). Wrington: West Country Design. OCLC 31076058.

- Ferson, E. B (1903). The tower clock and how to make it; a practical and theoretical treatise on the construction of a chiming tower clock, with full working drawings photographed to scale. Chicago: Hazlitt & Walker. OCLC 1145081500. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Leeming, Charles Frederick (1977). Langley, Peter (ed.). Langford and Churchill Guide. Sir John Wills. Churchill: Cliftonprint. OCLC 852053375.