Attingham Park

Attingham Park /ˈætɪŋəm/ is an English country house and estate in Shropshire. Located near the village of Atcham, on the B4380 Shrewsbury to Wellington road. It is owned by the National Trust. It is a Grade I listed building.

| Attingham Park | |

|---|---|

The entrance front, Attingham Park | |

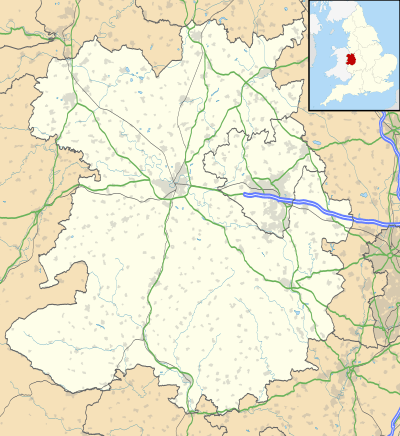

Location within Shropshire | |

| General information | |

| Type | Stately Home |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Location | near Atcham, Shropshire |

| Completed | Finished 1785 |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Website | |

| https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/attingham-park | |

| References | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Reference no. | 1055094[1] |

Attingham Park was built in 1785 for Noel Hill, 1st Baron Berwick, who received his title in 1784 during the premiership of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. Noel Hill was a politician who aided William Pitt in the restructuring of the East India Company. Noel Hill already owned a house on the site of Attingham Park called Tern Hall, but with money he received along with his title he commissioned the architect George Steuart to design a new and grander house to be built around the original hall. The new country house encompassed the old property entirely, and once completed it was given the name Attingham Hall.[2]

The Estate comprises roughly 4,000 acres, but during the early 1800s extended to twice that amount at 8,000 acres (3,000 hectares).[3] The extensive 640 acres (270 hectares) parkland and gardens of Attingham have a Grade II* Listed status. Over 470,000 people visited the house in 2017/18, placing it as the fourth most popular National Trust house.[4]

Across the 640 acre parkland there are five Grade II* listed buildings, including the stable block, the Tern Lodge toll house which can be seen on the B4380, and two bridges that span the River Tern. There are also twelve Grade II listed structures including the retaining walls of the estate, the bee house, the ice house, the walled garden, the ha-ha, which can be seen in the front of the mansion, and the Home Farm.

Historical use of the site

The archaeology of Attingham Park is diverse covering many different periods of history and human habitation. People have lived around the area of the estate for around 4,000 years since the Bronze Age, utilising the rich alluvial soils for agriculture. There are seven scheduled ancient monuments across the wider estate including an Iron Age settlement, Roman forts and a significant portion of the fourth largest civitas in Roman Britain, Viroconium, on the site of the nearby village of Wroxeter.[5]

There are also Saxon palaces, and a mediaeval village which was called Berwick Maviston. Today the remains of a moat and fish ponds from the old manor can still be seen. The manor and the village dated back to the Norman invasion, being mentioned in the 1086 Domesday book. The original manor fell into disrepair in mediaeval times; another house known as Grant's Mansion was recorded on the site in 1790. The village was occupied until the late 1700s when the newly created Baron Berwick built Attingham and removed the village from his land. The title of Baron Berwick comes from the name of this village.[6]

History

Attingham, including Cronkhill, was the seat of the Barons Berwick until that title became extinct in 1953. On the death of Thomas Henry Noel-Hill, 8th Baron Berwick (1877–1947) who died childless, the Attingham Estate, comprising the mansion and some 650 acres, was gifted to the National Trust.

Attingham Park was designed by George Steuart, a follower of James Wyatt, whose only surviving country house this is.[7] It was built from 1772 to 1785 for Noel Hill, 1st Baron Berwick, on the site of an earlier house called Tern Hall (which had been built to his own designs by Richard Hill of Hawkstone). The proportions have been criticised: for Simon Jenkins "The facade is uncomfortably tall, almost barracks-like, the portico columns painfully thin".[8] There is a large entrance court, with an imposing gatehouse, and two single storey wings stretch out to either side of the main block.

In 1805 John Nash added the picture gallery, a project that was flawed from the beginning as it suffered from leaks. Constructed using cast iron and curved glass to give the effect of coving, it throws light into the gallery below. In 2013 work began on building a new protective roof above the delicate Nash roof, replacing one installed in the 1970s with a new one which will stop leakage and reduce natural weather wear. The new roof will have temperature control, blinds, and UV resistant glass.[9] The 2nd baron went bankrupt, and all the contents of the house were auctioned in 1827; some were reacquired later.[10] The main reception rooms were divided into a male and female set on either side of the house. Angelica Kaufmann decorated a boudoir and there are three of her paintings in the drawing room.[11]

The nearby Italianate villa of Cronkhill on the estate is an important pioneer of this style in England. It was designed by John Nash for the 2nd Lord Berwick, as a generous gesture for his friend and agent, Francis Walford,[12] during the same time the Picture Gallery and staircase was being built. Once a part of the wider estate, it is now isolated on a hillside overlooking the riverside. Although the villa is owned by the National Trust, it is privately tenanted and only open for visitors a few days of the year.[13]

During the First World War, Attingham was owned by Thomas, the 8th Lord Berwick. He had let the property to the Dutch-American Van Bergen family who encouraged the establishment of a hospital for wounded soldiers at Attingham. The hospital opened in October 1914 and by 1918 had 60 beds and an operating theatre. During the First World War, the 8th Lord Berwick served with the Shropshire Yeomanry and as a diplomat in Paris. Throughout the war years he corresponded with Teresa Hulton, whom he married in June 1919. During the First World War, Teresa Hulton had worked with Belgian refugees in London and as a Red Cross nurse in Italy.[14]

Between 1948 and 1971 an Adult Education College occupied the hall, run by Sir George Trevelyan. In 1952 the Attingham Trust was set up by George Trevelyan and Helen Lowenthal, the purpose of the Attingham Trust being to offer American curators the opportunity to learn about British country houses. A summer school has been run by the Attingham Trust every year since 1952 and now takes in a diverse array of country houses around the United Kingdom including none National Trust properties. The Attingham name has since been used worldwide with the American Friends of the Attingham Trust being founded in 1962 in New York City, and the Attingham Society being founded in 1985. The Attingham Society covers the whole world and alongside the American Friends its purpose is to keep its members in touch and the continued education and interest of British country houses.[15]

Attingham Park is now the regional headquarters of the National Trust and also on the estate is the Shropshire office of Natural England.

The Estate

The park was landscaped by Humphry Repton and includes woodlands and a deer park, with between 200 and 300 head of Fallow deer (according to season).

The estate has a walled garden and an orchard, which grows fresh produce which is used on the estate in the tearooms, and sold to visitors. The meat from the Fallow deer is also sold in the shop during the shooting season, in winter and early spring.

The River Tern, which flows through the centre of the estate, joins the larger River Severn at the confluence just south of the Tern Bridge. Repton attempted to build a weir, the remains of which can now be seen, near the confluence but due to flooding it was washed away.

The park is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest due to it being home to many rare species of invertebrates. The amount of deadwood left by fallen trees around the parkland makes it the perfect habitat for a variety of different species, primarily beetles. There are seven units of SSSI around the park totalling to 190 hectares or 470 acres, nearly three-quarters of the entire estate.[16]

References

Bibliography

Douglas, Sarah (2011). Attingham: A story of love and neglect. The History Press/National Trust. ISBN 978-1-84359-361-4.

- Jenkins, Simon, England's Thousand Best Houses, 2003, Allen Lane, ISBN 0-7139-9596-3

Footnotes

- Historic England. "Attingham Park (1055094)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Douglas, p.4

- Douglas, p.40

- "National Trust Annual Report 2017/18" (PDF).

- Douglas, p.38

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1020281)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Jenkins, 638

- Jenkins, 638

- "Attingham Park restoration work starts". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- Jenkins, 638

- Jenkins, 638

- "A generous gesture for a friend" according to the National Trust; other sources imply that Walford was Nash's patron in this project.

- "Attingham Park Estate Cronkhill". National Trust. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "Attingham WWI Stories". Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "The Attingham Trust: About us". The Attingham Trust. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- "Site of Special Scientific Interest information" (PDF). Natural England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Attingham Park. |

- Attingham Park information at the National Trust

- BBC website panoramic view of Attingham Park and House

- www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Attingham Park and surrounding area today

- http://attinghamww1stories.wordpress.com/ : a blog telling the story of Attingham Park during the First World War

- http://attinghamparkmansion.wordpress.com/