John Cooke (Royal Navy officer)

John Cooke (17 February 1762 – 21 October 1805) was an experienced and highly regarded officer of the Royal Navy during the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars and the first years of the Napoleonic Wars. Cooke is best known for his death in hand-to-hand combat with French forces during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. During the action, his ship HMS Bellerophon was badly damaged and boarded by sailors and marines from the French ship of the line Aigle. Cooke was killed in the ensuing melee, but his crew successfully drove off their opponents and ultimately forced the surrender of Aigle.

John Cooke | |

|---|---|

John Cooke, painted c. 1797–1803 by Lemuel Francis Abbott | |

| Born | 17 February 1762 Tenterground in Goodman's Fields, London |

| Died | 21 October 1805 (aged 43) HMS Bellerophon off Cape Trafalgar |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1776–1805 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars |

|

Cooke, unlike many of his fellow officers, was never a notable society figure. He was however well respected in his profession and following his death was the subject of tributes from officers who had served alongside him. Memorials to him were placed in St Paul's Cathedral and his local church in Wiltshire.

Early life

John Cooke was born on 17 February 1762, the second son of Francis Cooke (1728–1792) and his wife, Margaret (1729–1796), née Baker.[1][n 1] Francis was the third son of the Reverend John Cooke and Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Dr. Thomas Sayer, Archdeacon of Surrey.[7] Margaret was the second daughter of Moses and Mary Baker, of the Parish of St Christopher le Stocks, in the City of London.[8][n 2] The Cooke family line had come from Devon, where they had been landowners and shipowners at Kenbury, near Exeter, and Topsham.[9] The Reverend John Cooke was a former rector of Chilbolton and Bishop's Waltham, and was appointed a Canon and 5th Prebendary of Winchester Cathedral by Bishop Trelawny.[10]

By 1750, Francis was established at Greenwich as an Admiralty ledger writer in the Cashiers' Branch of the Navy Pay Office, and as the Treasurer of the Greenwich Hospital, London.[11][n 3] Francis became a director of the Amicable Society for a Perpetual Assurance Office by 1775 and was appointed Cashier of the Navy on 17 July 1787 by The Right Honourable Henry Dundas.[12] Francis had married Margaret on 29 May 1757 at St Mary's, Chatham, Kent. John Cooke was baptised on 5 March 1762, at the Cooke's home in the Tenterground at Goodman's Fields, in the parish of St. Mary, Whitechapel. Sir John Bentley and William Henry Ricketts, were godfathers, Mrs Pigott of Bloomsbury Square, was godmother.[3][n 4]

Early naval career

John Cooke first went to sea at the age of eleven aboard the cutter HMS Greyhound under Lieutenant John Bazely, before going ashore to spend time at Mr Braken's naval academy at Greenwich. He was entered onto the books of one of the royal yachts by Sir Alexander Hood, who would become an enduring patron of Cooke's.[14] In 1776 he obtained a position as a midshipman on the ship of the line HMS Eagle, aged thirteen.[15] Cooke served aboard Eagle, the flagship of the North American Station, during the next three years, seeing extensive action along the eastern seaboard. Notable among these actions were the naval operations around the Battle of Rhode Island in 1778, when Eagle was closely engaged with American units ashore.[16] He distinguished himself in the assault, causing Admiral Lord Howe to remark "Why, young man, you wish to become a Lieutenant before you are of sufficient age."[14] On 21 January 1779, Cooke was promoted to lieutenant and joined HMS Superb in the East Indies under Sir Edward Hughes, but was forced to take a leave of absence due to ill-health.[14]

Cooke returned to England and then went to France to spend a year studying, before rejoining the navy in 1782 with an appointment to the 90-gun HMS Duke under Captain Alan Gardner.[14] Cooke saw action at the Battle of the Saintes, at which Duke was heavily engaged. He remained with Gardner following the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, bringing an end to the American War of Independence, and served as his first-lieutenant aboard his next command, the 50-gun HMS Europa.[14] Gardner became commodore at Jamaica, flying his broad pennant aboard Europa and retaining Cooke as his first-lieutenant until Cooke was injured in a bad fall and had to be invalided home.[14] He had recovered sufficiently by the time of the Spanish Armament in 1790 to be able to take up an appointment from his old patron, Sir Alexander Hood, to be third-lieutenant of his flagship, the 90-gun HMS London.[17] When the crisis passed without breaking into open war, London was paid off and Cooke went ashore.[14]

Frigate command

With the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in February 1793, Cooke rejoined Hood and became first-lieutenant of his new flagship, the 100-gun HMS Royal George, part of the Channel Fleet. On 21 February 1794, Cooke was promoted to commander and given his first independent command, the small fireship HMS Incendiary. Three months later, Incendiary was a signal repeater for the Channel Fleet during the Atlantic campaign of May 1794, relaying Lord Howe's signals to the fleet and operating as a scout in the search for the French fleet under Villaret de Joyeuse. On 1 June 1794, Cooke was a witness to the battle of the Glorious First of June, although his tiny ship was far too small to engage in combat.[18] In the action's aftermath, Cooke was included in the general promotions issued to the fleet, becoming a post captain on 23 July 1794. For a year, Cooke was stationed off Newfoundland as flag captain to Sir James Wallace aboard the 74-gun HMS Monarch, before returning to Britain and being offered command of the 28-gun HMS Tourterelle.[19] Cooke accepted, but when he found out she was ordered to the West Indies, he resigned it, having been told by Gardner that further service in the West Indies would likely kill him.[19]

Instead in early 1796 he took command of the 36-gun frigate HMS Nymphe. Nymphe was employed in the blockade of the French Atlantic ports over the next year, and on 9 March 1797 was in company with HMS St Fiorenzo when they encountered the returning ships of a short-lived French invasion attempt of Britain that had been defeated at Fishguard in Wales.[20] The French ships attempted to escape into Brest, but were hunted down by the British, who forced the surrender of Résistance and Constance in turn after successive short engagements.[21] Neither of the British ships suffered a single casualty in the combat, and both French ships were subsequently purchased into the Royal Navy, bringing prize money to Cooke and his crew.[22] Despite this success, Cooke was unpopular with his men due to the strict discipline he enforced aboard his ship. This was graphically demonstrated just two months after the action off Brest, when Nymphe became embroiled in the Spithead mutiny. Cooke attempted to assist Admiral John Colpoys at the mutiny's outbreak, and was ordered ashore by his crew when he tried to return to his ship. Cooke was tactfully removed from command by the Admiralty following the mutiny, although he was returned to service two years later aboard the new frigate HMS Amethyst in preparation for the Anglo-Russian invasion of the Batavian Republic.[15] During the invasion, Amethyst conveyed the Duke of York to the Netherlands and later participated in the evacuation of the force following the campaign's collapse.[19]

Cooke was involved in operations in Quiberon Bay during the remainder of 1799, and in 1800 participated in an abortive invasion of Ferrol. During this time, Amethyst captured six French merchant ships and small privateers.[23] During 1801, Cooke participated in the capture of the French frigate Dédaigneuse off Cape Finisterre, helping Samuel Hood Linzee and Richard King chase her down on 26 January. Amethyst was not heavily engaged with Dédaigneuse and received no damage, but aided in pursuing and trapping the French ship so that she could be seized. Dédaigneuse was later purchased into the Royal Navy as HMS Dedaigneuse.[24] Shortly afterwards, Cooke captured the Spanish ship Carlotta and the French privateer Général Brune in the same area.[25]

Trafalgar

With the Peace of Amiens, Cooke briefly retired on half-pay before being recalled to the fleet at the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars in 1803. Cooke was requested as flag captain by Admiral Sir William Young at Plymouth, but Cooke tactfully refused, instead applying for active service. He received command of HMS Bellerophon on 25 April 1805. In May, after the large combined French and Spanish fleet, under Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve escaped from Toulon, beginning the Trafalgar Campaign, Cooke was ordered to join a flying squadron under Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood. The squadron arrived off Cadiz on 9 June and Collingwood detached Bellerophon and three other ships to blockade Cartagena under Rear-Admiral Sir Richard Bickerton. When the combined fleet entered Cadiz on 20 August, Collingwood recalled Bickerton's force and mounted a blockade of the port. Collingwood was reinforced with more ships, and was later superseded by Nelson. Cooke was heard to say at this time that "To be in a general engagement with Nelson would crown all my military ambition".[16] Nelson had Villeneuve's fleet trapped in Cadiz and was blockading the harbour awaiting their expected attempt to escape.

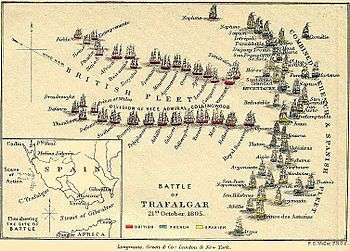

The Franco-Spanish fleet escaped Cadiz on 18 October 1805, but was soon chased down by Nelson and brought to battle on 21 October. Nelson formed his fleet into two divisions; the weather column would attack to the north under his direct command and the lee column would operate to the south under the command of Cuthbert Collingwood in HMS Royal Sovereign. Cooke was stationed fifth in Collingwood's line, and so was one of the first ships engaged in action with the combined fleet. Cooke took the unusual step of informing his first lieutenant William Pryce Cumby and his master Edward Overton of Nelson's orders, in case he should be killed.[26]

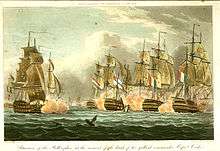

Bellerophon was soon closely engaged with the French, breaking through the enemy line and closing with Aigle. As with the other French ships in the fleet, Aigle's rigging and mastheads were occupied by musketeers and grenadiers, who kept up a steady fire on Bellerophon and took a heavy toll of sailors exposed on the British ship's deck. Much of the fire was directed at the quarterdeck, where Cooke, Cumby and Overton stood. Cumby noted with surprise that Cooke was still wearing his uniform coat, which sported epaulettes that marked him out as the ship's captain to French snipers. Cooke had forgotten to remove the epaulettes and recognised the danger they represented, but replied "It is too late to take them off. I see my situation, but I will die like a man".[15]

As the action continued, the Captain Pierre-Paul Gourège of Aigle ordered his crew to board and seize Bellerophon, hoping to use their superiority of numbers to overwhelm the British crew. Cooke sent Cumby below to make sure that the lower-deck guns continued to fire into the French ship as the battle continued overhead, and threw himself at the French sailors pouring onto Bellerophon's quarterdeck, shooting an enemy officer dead and engaging in hand-to-hand combat with the men behind him.[15] Within minutes Cumby had returned to the deck with reinforcements from below, passing the mortally wounded Overton on the ladder. The badly wounded ship's quartermaster was also present, and he informed Cumby that Cooke had fallen in the melee.[27] Cumby's charge cleared the French from the deck of Bellerophon, and he found Cooke dead on the quarterdeck, two musket balls lodged in his chest. Cooke's last words had been "Let me lie quietly a minute. Tell Lieutenant Cumby never to strike."[15]

Cumby took charge of the battered Bellerophon, directing her fire into Aigle and ultimately forcing the French ship's surrender after the arrival of other British vessels. Bellerophon had suffered grievously, losing 27 dead and 127 wounded.[27] Although Aigle was lost in the chaotic storm which followed the battle, Bellerophon survived, primarily due to Cumby's leadership. He was later promoted to post captain for his services in the action.[28] Cooke's body was buried at sea the day after the battle with the other fatal casualties from Bellerophon.[16]

Family and legacy

Cooke's death, as with those of George Duff and Admiral Nelson himself, was widely mourned in Britain. Cooke's widow Louisa and their eight-year-old daughter, Louisa Charlotte, were given numerous awards and presents, including the gold medal minted for the captains who had fought at the action, and a large silver vase presented by Lloyd's Patriotic Fund. The gold medal and vase were gifted to the nation by Caroline Augusta Rolles, Cooke's great-granddaughter, after her on death on 14 January 1931.[n 5]

At least some of the money the family received was spent on a large wall plaque mounted in St Andrew's Church in Donhead St Andrew in Wiltshire, close to the family home at Donhead Lodge in St Bartholomew's Street.[30] The plaque commemorates Cooke's life and death and also that of his wife. A memorial was also raised to him in St Paul's Cathedral. Tributes from fellow officers were also forthcoming, including from the future explorer John Franklin, who had served on Bellerophon at Trafalgar and had said of Cooke that he was "very gentlemanly and active. I like his appearance very much."[15] A number of letters that Cooke wrote to his brother prior to Trafalgar are held by the National Maritime Museum.[31]

Cooke had married Louisa, née Hardy, on 15 June 1790 at St Leonard's, Shoreditch. Louisa was the fourth daughter of Josiah Hardy, the former Governor of New Jersey, and later consul at Cadiz.[14] Cooke had leased Donhead Lodge from Baron Henry Arundell in 1803 and Louisa remained in residence there until 1813.[32] She died at her home, 9 Montpellier Terrace, Montpellier, Cheltenham, on (aged 96).[33] The funeral was held at St Peter's Church, Leckhampton, on 11 February 1853, with interment following in the churchyard.[34][n 6]

Louisa Charlotte Cooke, their only child, was born on 26 January 1797 at Stoke Damerel.[14] Louisa Charlotte married Abraham John Newenham Devonsher of Kilshanick, County Cork, at Cheltenham, on 9 March 1820.[35] Formerly of Hinton Charterhouse, she died after a short illness at St Anne’s, Albion Street, Cheltenham, on 30 April 1871 (aged 74).[36][n 7] She was interred at Bouncer's Lane Cemetery, Prestbury, Cheltenham, on 5 May 1871.[37][n 8]

References

- Howard 1896, p. 51; Tracy 2006, p. 95.

- Register of Baptisms, Saint Mary, Whitechapel, p. 85, 5 March 1762.

- Howard 1896, p. 51.

- Land Tax Assessment Book, Saint Mary, Whitechapel 1762, p. 73.

- Journal of the House of Commons 2 November 1780, p. 256, Vol. 38.

- Howard 1896, p. 51; Register of Baptisms, Saint Mary, Whitechapel, p. 29, 8 August 1759.

- Burke 1852, p. 16.

- Howard 1896, p. 51; Freshfield 1882, p. 41.

- Stevens 1969, p. 40.

- Burke 1852, p. 16; Clergy of the Church of England 1717.

- Stevens 1969, p. 40; Tracy 2006, p. 95.

- Urban 1843, p. 202; Barfoot 1791, p. 354; Perpetual Assurance Office 1778, pp. 9, 34; Sheffield Register 21 July 1787, p. 2.

- Chatterton-Newman 2020.

- Tracy 2006, p. 95.

- White 2005, p. 48.

- Laughton 2004.

- Tracy 2006, p. 95; Laughton 2004.

- James 2002, p. 126, Vol. 1.

- Tracy 2006, p. 96.

- James 2002, p. 80, Vol. 2.

- Henderson 1994, p. 45.

- "No. 14035", The London Gazette, 8 August 1797, p. 764.

- "No. 15301", The London Gazette, 11 October 1800, p. 1176.

- James 2002, p. 136, Vol. 3.

- "No. 15412", The London Gazette, 29 September 1801, p. 1203.

- White 2005, p. 47.

- James 2002, p. 52, Vol. 4.

- White 2005, p. 52.

- Cheltenham Chronicle 17 January 1931, p. 2.

- White 2005, p. 49; Hawkins 1995, p. 30; Pugh, Crittall & Crowley 1953, p. 127.

- National Maritime Museum 1805.

- Wiltshire and Swindon Archives 1820; Hawkins 1995, p. 30.

- Cheltenham Chronicle 10 February 1853, p. 3.

- Register of burials, St Peter, Leckhampton 1853, p. 12, 11 February 1853.

- Cheltenham Chronicle 16 March 1820, p. 3.

- The Times 8 May 1871, p. 1.

- Register of burials, St Mary, Cheltenham 1871, p. 40.

Footnotes

- A number of sources, including T. A. Heathcote's Nelson's Trafalgar Captains and Their Battles, Colin White's The Trafalgar Captains and John Knox Laughton's entry for Cooke in the Dictionary of National Biography give a birth year of 1763 and omit most information about Cooke's early life. Nicholas Tracy's entry in Who's Who in Nelson's Navy provides fuller coverage of Cooke's early life, and includes a specific baptism date. Cooke's baptism register entry, for the parish of St Mary, Whitechapel, records that he was "borne [sic] 17th February" and baptised "in 4 Tenters".[2] Tenters was then part of the Tenterground in Goodman's Fields, London. J. J. Howard's Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica states the same birth and baptism date (as well as naming godparents), and goes further, by stating that the baptism took place at the Cooke's home.[3] Furthermore, Cooke's father, Francis, is recorded in the 1762 Land Tax Assessment Book for the Parish of Saint Mary, Whitechapel, as residing between Alie Street and Leman Street (West side), close to the corner of North and East Tenter streets.[4] At the time, Francis worked as a ledger writer at the nearby Navy Pay Office on Broad Street.[5] Lastly, Cooke's elder brother, Christopher, was also baptised at the Cooke's home in the parish of St Mary, on 8 August 1759, and the baptism register entry records that he was baptised "in the Tenter Ground Goodman [sic] Fields".[6]

- For the register of marriage, see entry number 196 in the Register of marriages, St Mary, Chatham, 29 May 1757, p. 50, (p. 30 in the PDF).

- For the location of the Navy Pay Office, see "No. 10292", The London Gazette, 1 March 1763, p. 3.

- Probably Jane Pigott the wife of Thomas Pigott. Jane was godmother to Cooke's younger sister Jane. Thomas was the godfather to Cooke's elder sister Margaret.[3] William Henry Ricketts of New Canaan Plantation, St James, Jamaica, and Longwood, Hampshire.[13]

- Ada Louisa Rolles died on 18 April 1931 and left her interest in the gold medal and vase to her sister Caroline Augusta for life, and afterwards, to the Greenwich Hospital.[29]. For the details of Ada Louisa's bequest see Cheltenham Chronicle 25 June 1930, p. 4. For the Greenwich Hospital bequest records, see List of Admiralty Records 1964, 1930–1931, p. 145.

- For the location of the grave and inscription, see Rawes 2019, p. 119, Grave identification K14 (p. 4 in the PDF).

- For Louisa's probate notice and previous residence, see London Daily News 9 January 1872, p. 7. For Louisa's place of death, see Cheltenham Examiner 3 May 1871, p. 2.

- For the gravestone inscription, see Blacker 1890, p. 310.

- For the approximate centroid of North-, South-, West-, and East- Tenter Street, and Tenter Passage, in Goodman's Fields, London 51.51251°N 0.07159°W.

Bibliography

Books

- Barfoot, Peter (1791). The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce, and Manufacture. 1. London: John Wilkes. OCLC 33982916.

- Blacker, Reverend Beaver Henry, ed. (1890). Gloucestershire Notes and Queries. 4. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, & Co., Limited. OCLC 982665719. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Burke, Bernard (1852). A visitation of the seats and arms of the noblemen and gentlemen of Great Britain. 2. London: Hurst and Blackett (successors to Henry Colburn). OCLC 3257884. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Freshfield, Edwin, ed. (1882). The register book of the parish of St Christopher le Stocks, in the city of London. 1. London: Printed by Rixon and Arnold. OCLC 2683227. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1780–1782). Journals of the House of Commons. 38. London: By order of the House of Commons. OCLC 1751506. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

The Examination of Francis Cooke

- Hawkins, Desmond (1995). The Grove diaries: the rise and fall of an English family, 1809-1925. Dorset: Dovecote Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-600-5. OCLC 32892163.

- Henderson, James (1994) [1970]. The Frigates: An account of the lighter warships of the Napoleonic wars 1793-1815. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-432-1. OCLC 1023686570. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Howard, Joseph Jackson, ed. (1896). Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica. Third Series. 4. London: Mitchell and Hughes. OCLC 1141272165. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain: During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, Volumes 1-6, 1793-1827. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-905-8. OCLC 265568758.

- Perpetual Assurance Office (1778). A List of the Members of the Corporation of the Amicable Society. London. OCLC 561763637. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Public Record Office (1964). Lists and indexes. Supplementary Series. No. VI. List of Admiralty Records. Various classes. 1914 - 1945. 6. Millwood, New York: Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited. ISBN 978-0-527-03976-9. OCLC 63630242. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Pugh, R. B.; Crittall, Elizabeth; Crowley, D. A. (1953). A History of Wiltshire. Institute of Historical Research, University of London. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-722735-0. OCLC 289108.

- Stevens, Joan (1 October 1969). The Friends of the Turnbull Library (ed.). John George Cooke and his literary connections. The Turnbull Library Record. Alexander Turnbull Library Endowment Trust. 2. New Zealand. pp. 40–55. ISSN 0110-1625. OCLC 1089680628. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-244-3. OCLC 62306661.

- Urban, Sylvanus, ed. (1843). The Gentleman's Magazine. July to December inclusive. 20 (175 ed.). London: William Pickering; John Bowyer Nichols and Son. hdl:2027/mdp.39015004754332. OCLC 1570611.

- White, Colin (2005). The Trafalgar Captains: Their Lives and Memorials. The 1805 Club. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-247-4. OCLC 469507654.

Web

- Chatterton-Newman, Roger (2020). "William Henry Ricketts (1736–1799) of New Canaan Plantation, St James, Jamaica, and Longwood, Hampshire". Legacies of British Slave-ownership database. London: University College London. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Cook, John". Clergy of the Church of England Database. London: King's College London. 1717–1744. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Laughton, John Knox (2004). "Cooke, John (1763–1805), naval officer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Revised by Andrew Lambert (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6171. Retrieved 23 May 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rawes, Julian (27 December 2019). Miller, Eric (ed.). "Burials in St Peter's Churchyard - Tombstone Inscriptions - Section K" (PDF). Leckhampton Local History Society (Additional comments by Eric Miller. Later additions from Eric Miller added by Paul McGowan ed.). Leckhampton: Gloucestershire Family History Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

Newspapers

- "London, July 17". Sheffield Register, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, & Nottinghamshire Universal Advertiser. 21 July 1787. p. 2. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Marriage". Cheltenham Chronicle. 16 March 1820. p. 3. OCLC 751668290. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Died". Cheltenham Chronicle. 10 February 1853. p. 3. OCLC 751668290. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Deaths". Cheltenham Examiner. 3 May 1871. p. 2. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Deaths". The Times. 8 May 1871. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Louisa Charlotte Devonsher". London Daily News. 9 January 1872. p. 7. OCLC 751658958. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- "Cheltenham Lady's Will. Bequests to Charitable Organisations". Cheltenham Chronicle. 25 June 1930. p. 4. OCLC 751668290. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Death of Miss C. Rolles. Trafalgar Hero Descendant. Relics to go back to nation". Cheltenham Chronicle. 17 January 1931. p. 2. OCLC 751668290. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

Archives

- 12 deeds of Donhead Lodge, Donhead St Andrew (Abstract of Title). Chippenham: Wiltshire and Swindon Archives. 1806–1835. 2637/2. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Cooke, John (1805). Captain John Cooke. A collection of 6 letters (Letters). Greenwich: National Maritime Museum Manuscripts Collection. AGC/33/8. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Parish of Saint Mary, Whitechapel, Land Tax Assessment Book (Microfilm). London: London Metropolitan Archives. 1762. p. 73. CLC/525/MS06015/030 (former reference MS 06015/30). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Register of Baptisms (Microfilm). London: London Metropolitan Archives. 1758–1774. p. 43. P93/Mry1/010 (Microfilm Reference X024/088). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Register of burials for the parish of St Peter, Leckhampton (Digital image). Gloucester: Gloucestershire Archives. 1850–1866. p. 11. P198/1/IN/1/16. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Bishop's Transcripts for Cheltenham New Burial Ground 1864 to 1876 (Microfilm). Gloucester: Gloucestershire Archives. 1864–1876. p. 215. GDR/V1/511. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Register of marriages and banns, St Mary, Chatham (PDF) (Digital image). Strood: Medway Archives. 1754–1762. p. 50. P85/1/45. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

Further reading

- Hore, Peter (2015). Nelson's band of brothers: Lives and memorials. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-779-5. OCLC 1123940748.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (2010) [1807]. "Biographical Memoir of the Late Captain John Cooke". Containing a General and Biographical History of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom with a Variety of Original Papers on Nautical Subjects. The Naval Chronicle. 17. Cambridge Library Collection. ISBN 978-0-511-73171-6. OCLC 1118491892.