HMS Royal Sovereign (1786)

HMS Royal Sovereign was a 100-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy,[1] which served as the flagship of Admiral Collingwood at the Battle of Trafalgar. She was the third of seven Royal Navy ships to bear the name. Designed by Sir Edward Hunt, she was launched at Plymouth Dockyard on 11 September 1786,[1] at a cost of £67,458, and was the only ship built of her time built to such a large draught (limiting her access to shallow waters). Due to the high number of Northumbrians on board the crew were known as the Tars of the Tyne.[2]

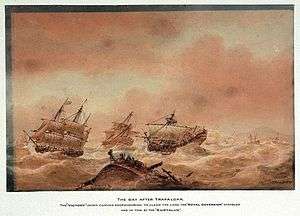

The day after Trafalgar, Victory under canvas endeavouring to clear the land while Royal Sovereign is disabled and in tow by Euryalus, in the collection of the National Maritime Museum; Nicholas Pocock; 19th century. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Royal Sovereign |

| Ordered: | 3 February 1786 |

| Builder: | Plymouth Dockyard |

| Laid down: | 7 January 1774 |

| Launched: | 11 September 1786 |

| Renamed: | HMS Captain, 17 August 1825 |

| Honours and awards: | Participated in: |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1841 |

| Notes: | Harbour service from 1826 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type: | 100-gun first-rate ship of the line |

| Tons burthen: | 2175 (bm) |

| Length: | 183 ft 10 1⁄2 in (56.0 m) (gundeck) |

| Beam: | 52 ft 1 in (15.88 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 22 ft 2 1⁄2 in (6.8 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Sail plan: | Full rigged ship |

| Armament: | |

In service

Royal Sovereign was part of Admiral Howe's fleet at the Glorious First of June, where she suffered 14 killed and 41 wounded.[3]

On 16 June 1795, as the flagship of Vice-Admiral William Cornwallis, she was involved in the celebrated episode known as 'Cornwallis' Retreat'.[3]

On 17 March 1796 the Bellisarius Transport collided with her and sank, a witness on HMS Mars wrote in a private letter that the accident was occasioned by a dispute between the Master and the second Mate when wearing ship; by which, not paying; proper attention, they fell athwart the Royal Sovereign, when the Sovereign's gib-boom and bowsprit took their main-mast, and struck her amid ship, by which she almost 'instantly sunk.' To add to the distress of this dreadful scene an unhappy woman, with her infant in her arms, who stood on the quarter-deck of the Bellisarius, attempted to save the life of her infant by throwing it on board the Royal Sovereign at the instant of the two ships meeting, but unfortunately it fell between the two ships sides, and was crushed to atoms before the eyes of its unhappy mother, who in her distraction of mind, instantly precipitated, herself. into the sea, and shared the-grave of her child.[4]

Trafalgar

Under Admiral Collingwood she was the first ship of the fleet in action at Trafalgar on 21 October 1805, she led one column of warships; Nelson's Victory led the other. Due to the re-coppering of her hull prior to her arrival off Cádiz, Royal Sovereign was a considerably better sailer in the light winds present that day than other vessels, and pulled well ahead of the rest of the fleet. As she cut the enemy line alone and engaged the Spanish three decker Santa Ana, Nelson pointed to her and said, 'See how that noble fellow Collingwood carries his ship into action!' At approximately the same moment, Collingwood remarked to his captain, Edward Rotheram, 'What would Nelson give to be here?'[5]

Royal Sovereign and Santa Ana duelled for much of the battle, with Santa Ana taking fire from fresh British ships passing through the line, including HMS Mars and HMS Tonnant, while nearby French and Spanish vessels fired on Royal Sovereign. Santa Ana struck at 14:15, having suffered casualties numbering 238 dead and wounded after battling Royal Sovereign and HMS Belleisle. Royal Sovereign lost her mizzen and mainmasts, her foremast was badly damaged and much of her rigging was shot away.[6] At 2.20 pm Santa Ana finally struck to Royal Sovereign.[7] Shortly afterwards a boat came from Victory carrying Lieutenant Hill, who reported that Nelson had been wounded. Realising that he might have to take command of the rest of the fleet and with his ship according to his report being "perfectly unmanageable",[8] by 3 pm he signalled for the frigate Euryalus to take Royal Sovereign in tow.[7] Euryalus towed her round to support the rest of the British ships with her port-side guns, and became engaged with combined fleet's van under Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley, as it came about to support the collapsing centre.[9] Fire from the lead ships shot away the cable between Royal Sovereign and Euryalus, and the latter ship made off towards Victory.[10] Royal Sovereign exchanged fire with the arriving ships, until Collingwood rallied several relatively undamaged British ships around Royal Sovereign, and Dumanoir gave up any attempt to recover some of the prizes, and made his escape at 4.30pm.[11]

At 4.40 pm one of Victory's boats, carrying Captain Henry Blackwood and Lieutenant Hill, came alongside and Blackwood reported Nelson's death to Collingwood.[12] This left Collingwood in command of the fleet, and with a storm rising, and disregarding Nelson's final order to bring the fleet to anchor, Collingwood ordered Blackwood to hoist the signal to all ships to come to the wind on the starboard tack, and to take disabled and captured ships in tow.[13] Royal Sovereign was by now almost or totally unmanageable and virtually uninhabitable.[14] As she had most of her masts shot away she could not make signals.[13] Having his ship too much disabled by enemy fire[15] at just before of 6 pm Collingwood, who had succeeded Nelson in command of the fleet had to transfer himself and his flag to the frigate Euryalus,[15] while Euryalus sent a cable across and took Royal Sovereign in tow for second time.[13] At the end of the action Collingwood signalled from the frigate to the rest of the fleet to prepare to anchor. HMS Neptune took over the tow on 22 October, and was replaced by HMS Mars on 23 October.[6][16] Royal Sovereign had lost one lieutenant, her master, one lieutenant of marines, two midshipman, 29 seamen, and 13 marines killed, and two lieutenants, one lieutenant of marines, one master's mate, four midshipman, her boatswain, 69 seamen, and 16 marines wounded.[17]

After Trafalgar

Royal Sovereign returned to duty in the Mediterranean the next year and remained on the blockade of Toulon until November 1811, when she was ordered to return home to the Channel Fleet. In 1812 and 1813 she was under the command of Rear Admiral James Bissett serving under Admiral Keith.[18]

She was credited with the capture on 5 August 1812 of the American ship Asia, of 251 tons, which had been sailing from St. Mary's to Plymouth with a cargo of timber.[19] Royal Sovereign shared the proceeds of the capture with all the vessels in Keith's squadron, suggesting that what happened was that Asia sailed into Plymouth unaware that the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States had broken out and was seized as she arrived, the formal credit going to the flagship.[Note 1]

After her useful active life she was converted to harbour service as a receiving ship at Plymouth before being renamed HMS Captain[21] on 17 August 1825. Hulked in June 1826, Captain was finally broken up at Plymouth,[1] with work being completed on 28 August 1841. Four of her guns were saved and are incorporated in the Collingwood Memorial in Tynemouth.

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

Citations

- Lavery, Ships of the Line vol.1, p178.

- Famous Fighters of the Fleet, Edward Fraser, 1904, p.202

- Ships of the Old Navy, Royal Sovereign (1).

- https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42272072/the_bellasarius_transport_sinking_march/

- Heathcote. Nelson's Trafalgar Captains. p. 41.

- Adkin. The Trafalgar Companion. p. 323.

- Clayton. Trafalgar. p. 214.

- Newbolt. p.124

- Clayton. Trafalgar. p. 243.

- Clayton. Trafalgar. p. 249.

- Clayton. Trafalgar. pp. 242–5.

- Goodwin. The Ships of Trafalgar. p. 19.

- Clayton. Trafalgar. p. 257.

- Pocock p.141

- Duke Younge p.334

- Clayton. Trafalgar. p. 301.

- William p.45

- Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy, David Bonner Smith

- "No. 16715". The London Gazette. 27 March 1813. p. 627.

- Keith's share was worth £85 17s 6½d."No. 17229". The London Gazette. 11 March 1817. p. 614.

- Ships of the Old Navy, Royal Sovereign (2).

References

- Adkin, Mark (2007). The Trafalgar Companion: A Guide to History's Most Famous Sea Battle and the Life of Admiral Lord Nelson. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-84513-018-9.

- Clayton, Tim; Craig, Phil (2004). Trafalgar: The Men, the Battle, the Storm. London: Hodder. ISBN 0-340-83028-X.

- Goodwin, Peter (2005). The Ships of Trafalgar: The British, French and Spanish Fleets October 1805. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-84486-015-9.

- Heathcote, T. A. (2005). Nelson's Trafalgar Captains and their Battles: A Biographical and Historical Dictionary. Barnsley: Pen& Sword Maritime. ISBN 1-84415-182-4.

- Lavery, Brian (2003) The Ship of the Line – Volume 1: The development of the battlefleet 1650–1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

- Duke Yonge, Charles. The history of the British navy V2, from the earliest period to the present time R.Bentley Publishing. ISBN 1-104-39362-X

- San Juan, Victor. (2009) Trafalgar. Tres armadas en combate (Spanish Edition) (Kindle Edition) ASIN B00332FJT4

- Pocock, Tom. (2005) Trafalgar: An Eyewitness History. Penguin Best sellers. ISBN 0-14-144150-X

- Williams, James. The naval history of Great Britain from the declaration of war by France in 1793 to the accession of George IV, Conway Maritime Press Ltd (2003). ISBN 0-85177-905-0

- Henry Newbolt. (2008) The Year Of Trafalgar Being An Account Of The Battle And Of The Events Which Led Up To It, With A Collection Of The Poems And Ballads Written Thereupon Between 1805 And 1905, Loney Press. ISBN 1-4437-1872-6

- Winfield, Rif (2007) British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.

- Michael Phillips. Royal Sovereign (100) (1786) (1). Michael Phillips' Ships of the Old Navy. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Michael Phillips. Royal Sovereign (100) (1786) (2). Michael Phillips' Ships of the Old Navy. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Lincoln P. Paine. Warships of the world to 1900 Mariner Books.

External links