January 2018 North American blizzard

The January 2018 North American Blizzard was a powerful blizzard that caused severe disruption along the East Coast of the United States and Canada. The storm dropped up to 2 feet (61 cm) of snow in the Mid-Atlantic states, New England, and Atlantic Canada, while areas as far south as southern Georgia and far northern Florida had brief wintry precipitation, with 0.1 inches of snow measured officially in Tallahassee, Florida.

Category 1 "Notable" (RSI: 2.55) | |

Part of the 2017–18 North American winter | |

GOES-16 satellite image of the blizzard rapidly deepening off the Northeastern United States at 13:45 UTC (8:45 a.m EST) on January 4, 2018. | |

| Type | Extratropical cyclone Nor'easter Bomb cyclone Winter storm Ice storm Blizzard |

|---|---|

| Formed | January 2, 2018 |

| Dissipated | January 6, 2018 |

| Lowest pressure | 949 mb (28.02 inHg) |

| Highest winds |

|

| Highest gust | 126 mph (203 km/h) in Saint-Joseph-du-Moine, Nova Scotia |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion | Snowfall – 24.0 in (61 cm) in Bathurst, New Brunswick Ice – 0.5 in (1.3 cm) in Brunswick, Georgia[1] |

| Damage | $1.1 billion (2018 USD)[2] |

| Power outages | ≥ 300,000 |

| Casualties | 22 confirmed |

| Areas affected | Cuba, The Bahamas, Bermuda, Southeastern United States, Northeastern United States, New England, Atlantic Canada |

The storm originated on January 3 as an area of low pressure off the coast of the Southeast. Moving swiftly to the northeast, the storm explosively deepened while moving parallel to the Eastern Seaboard, causing significant snowfall accumulations. The storm received various unofficial names, such as Winter Storm Grayson, Blizzard of 2018 and Storm Brody. The storm was also dubbed a "historic bomb cyclone".[3]

On January 3, blizzard warnings were issued for a large swath of the coast, ranging from Norfolk, Virginia all the way up to Maine. Several states, including North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts declared states of emergency due to the powerful storm. Hundreds of flights were canceled ahead of the blizzard. Overall, 22 people were confirmed to have been killed due to the storm, and at least 300,000 residents in the United States lost power in total.

Meteorological synopsis

Early on January 1, the Weather Prediction Center (WPC) began to anticipate the possibility of a northward-tracking area of low pressure that would bring wintry precipitation to much of the East Coast of the United States in the first week of January,[4] exacerbating an extended period of anomalously cold weather.[5] Due to modeling confining of precipitation to relatively narrow bands at the time, initial forecasts on the storm's impacts were uncertain.[4] The storm's development was forecast to originate from the eastward progression of a shortwave trough originating from the northern Rocky Mountains,[6] strengthening due to the presence of a longwave trough situated over the Eastern United States.[7] However, as the anticipated event drew closer, the system's genesis grew increasingly complex with the development of two separate disturbances in the jet stream over the upper Mississippi Valley and the eastern extent of the Rocky Mountains; these two would shape the eventual coverage of wintry precipitation associated with the storm.[5] As the troughs pushed eastward, frontogenesis along the trough and a resulting increase in moisture allowed for freezing rain to commence over areas of northern Florida and southern Georgia early on January 3.[8] Later that day, rapid cyclogenesis led to the formation of the forecast low-pressure area north of the Bahamas and east of Jacksonville, Florida,[9] with cloud cover quickly expanding to the north and east ahead of the storm's center; consequently, the WPC began issuing regular storm summaries at 21:00 UTC (4:00 p.m. EST) on January 3.[10]

After forming, the extratropical cyclone continued to explosively deepen, tracking northward parallel to the United States East Coast.[11] By the morning of January 4, the powerful storm system had deepened by 53 mbar (hPa; 1.57 inHg) in 21 hours—one of the fastest rates ever observed in the Western Atlantic[12]—to a pressure of 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg), with a coastal cold front focusing heavy snowfall and thundersnow along immediate coastal regions.[13] The drop in pressure was over twice the threshold (24 mbar (hPa; 0.71 inHg) in 24 hours) for bombogenesis.[14] Onshore, the inland extent of wintry precipitation gradually increased as the storm intensified.[15] As the day progressed, the development of several intense snowbands allowed for heavy snowfall rates of up to 3 in (7.6 cm) per hour over New England,[16][17] which were enhanced further by the influx of warm low-level air due to the cyclone's circulation.[18] The storm bottomed out at a pressure of 950 mbar (hPa; 28.05 inHg) when it was centered about 120 mi (190 km) southeast of Nantucket Island.[19] The cyclone's intensity held steady as it moved north into the Bay of Fundy late on January 4.[1] Afterwards, it began weakening and ultimately dissolved into a trough on January 6.

Preparations and impact

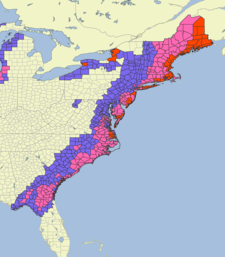

| |||||

| Blizzard warning | |||||

| Winter storm warning | |||||

| Winter weather advisory | |||||

The blizzard produced snowfall and other forms of frozen precipitation across much of the United States Eastern Seaboard. As of the WPC's fifth winter storm summary, the highest official snowfall amount recorded is 17.0 in (43 cm) in Cape May Court House, New Jersey; however, a snowfall total of 52 cm (20 in) was reported Bathurst, New Brunswick. Freezing rain totals peaked at 0.5 in (1.3 cm) in Brunswick, Georgia and near Folkston, Georgia.[19] At least twenty-two fatalities were attributed to the storm, including at least eight car accident-related deaths. At least 4,020 flights were cancelled across the United States, with a majority of cancellations caused by the extensive winter storm.[20] Insurers estimate that claims relating to coastal flooding from the storm will be more than those from snow-related damage.[21]

Southeastern United States

Florida and Georgia

Florida A&M University and Florida State University, announced closures for January 3.[22] Governor of Georgia Nathan Deal declared a state of emergency for 28 counties.[23] 1.2 inches of snowfall was recorded at Savannah, Georgia. [23] while Tallahassee, Florida received 0.1 inches of snow officially. For this region it was the first snow fall since December 1989. Additionally, this is the first recorded measurable snowfall in Tallahassee during the month of January based on records dating back to April 1885. [24]

The snowfall forced the closure of Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport, cancelling 78 incoming and outgoing flights.[25] Ice accumulation was reported as far south as northern Levy County, Florida.[26] Widespread power outages affected much of the Southeast U.S. coast during the storm's infancy; nearly 100,000 electricity customers were without power in the Florida-Georgia border region,[27] including over 6,000 in Glynn County, Georgia. Heavy icing downed trees and power lines throughout St. Simons Island, Georgia, causing extensive power outages.[28] Power outages impacted Nassau County, Florida to a similar extent, prompting the opening of an emergency shelter in Hilliard, Florida.[29] .[30] Four Central Florida counties also opened cold weather shelters when temperatures fell below 45 F. [31] Icy conditions forced numerous road closures, including an 80 mi (130 km) stretch of Interstate 10 between Tallahassee, Florida and Live Oak, Florida. All lanes of Interstate 75 in Hamilton County, Florida to facilitate de-icing.[32]

The Carolinas

.jpg)

Snowfall in South Carolina peaked at 7.3 in (19 cm) in Summerville.[13] Charleston recorded the third highest daily snowfall total in its history at 5.3 in (13 cm) and the highest total since 1989.[33][13][26] The runways of Joint Base Charleston, used jointly with Charleston International Airport, were closed by the United States Air Force. A state of emergency was declared and a curfew enforced for much of Dorchester County.[33] On January 4, the South Carolina National Guard was deployed to assist impacted areas and the South Carolina Highway Patrol and South Carolina Department of Transportation to recover vehicles.[34] One person was killed in a traffic collision on Interstate 95 in Clarendon County due to icy road conditions following the storm's passage.[35] Governor of North Carolina Roy Cooper activated the state's emergency operations center on January 3 and declared a state of emergency for 54 counties.[36] Due to the inclement conditions, 66 North Carolina school districts issued cancellations, affecting thousands of students.[37] Local snowfalls in excess of 0.5 in (1.3 cm) occurred across the eastern half of the state. Wilmington, North Carolina observed 3.8 in (9.7 cm) of snowfall, marking the city's highest total since 2011. Along the Outer Banks, gusts in excess of 70 mph (110 km/h) caused rough seas, resulting in coastal flooding. Water levels rose 3 ft (0.91 m) above normal in Buxton, North Carolina.[26] Four people were killed in the state, including two each in Moore and Beaufort counties and one in Surf City. At the height of the storm, around 20,000 utility customers lost power in the state.[37] Poor driving conditions resulted in around 900 vehicle crashes across North Carolina.[38]

Mid-Atlantic states

Governor of Virginia Terry McAuliffe declared a state of emergency in the state on January 3.[39] In Virginia Beach, the storm maintained gusts of 50–55 mph (80–89 km/h) for several hours.[12] In one 24-hour period, 118 crashes occurred in the Hampton Roads area, with another 121 disabled vehicles reported.[40] Across the entirety of the state, Virginia troopers responded to 245 vehicular collisions.[41] Gusts in the Hampton Roads area peaked at 69 mph (111 km/h) in Tangier, with lesser gusts farther inland.[42] Due to the local geography, water levels in Chesapeake Bay fell in response to the storm's circulation passing to the east; the Patapsco River near Fort McHenry fell 3.49 ft (1.06 m) below the mean low water level, reaching its lowest height since 1989.[43] The United States Coast Guard restricted maritime access to the Port of Baltimore from the evening of January 3 into January 5.[44]

New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut

New York City encountered 30 mph winds, and JFK Airport temporarily suspended flights due to whiteout conditions. Central Park reported 9.8 inches (250 mm) of snow.[45] Governor of New York Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency for Westchester County, New York City, and Long Island.[46]

New Jersey experienced as much as 17.0 inches (430 mm) of snow in some places, with Islip on Long Island, NY reaching 16 inches (410 mm) of snow; however, tropical storm-force winds blew the snow into banks as high as 3 feet (0.91 m) in certain areas. In Connecticut, the National Weather Service office in Bridgeport recorded 9.0 inches of snow and wind gusts to 52 mph.

New England

Being the most geographically proximate to the storm's track, Massachusetts bore the highest impacts of all American states. Winds gusted to hurricane-force at 76 miles per hour (122 km/h) on Nantucket and over 70 mph (110 km/h) on mainland Massachusetts.[47]

At least 17.0 inches (430 mm) of snow fell on the Boston area, and 14.1 inches (360 mm) fell in Providence, Rhode Island. In Boston, a storm tide of 15.16 ft (4.62 m) was recorded during the blizzard which flooded areas of the financial district, including a subway station.[48][49] This beat the previous record set in 1978 by the Blizzard of 1978.[48] Significant coastal flooding occurred in Maine and New Hampshire.[12]

Atlantic Canada

After ravaging New England, the storm moved on to Atlantic Canada on January 4 and 5. Heavy snow fell in New Brunswick, peaking at 60 centimeters (24 in) in Bathurst. Sydney reported snowfall rates of up to 8 cm per hour, in heavy bands of thundersnow. While snowfall amounts closer to the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia were very low, winds gusting up to 203 km/h (126 mph) were reported in Saint-Joseph-du-Moine, causing widespread power outages. At the peak of the storm, nearly 130,000 Nova Scotia Power customers were left without power, while in New Brunswick, around 19,000 NB Power customers were left without power. Offshore waves reached heights of 16 m (52 ft).[50]

Bermuda

On 5 January 2018, the storm was also responsible for a persistent thunderstorm that brought 1.84 inches (47 mm) of rain and gale-force winds to the island of Bermuda. There were wind gusts of up to 52 miles per hour (84 km/h; 45 kn).[51]

Cruise ships

On 4 January 2018, both the Norwegian Breakaway and the Norwegian Gem traveled through the storm causing major flooding in passenger staterooms. The Breakaway, with 4,000 passengers, was sailing from the Bahamas back to New York City when it sustained flooding throughout the passenger cabins as well as elevators and the hallways. Some rooms were so badly flooded that some passengers slept in the public spaces. Footage of the ordeal showed the sides of the ship being hit by waves as high as 30 feet (9.1 m). At some points in the trip, the ship tilted so much that some passengers fell out of their beds. There was widespread damage to the interior as glasses fell out of shelves and some furniture toppled over. Paintings in the art gallery could be seen falling off the walls as the ship tilted due to the turbulent seas. Seasickness was widespread as guests could be seen vomiting. While Norwegian Cruise Line released a formal apology, the incident has sparked outrage with some guests were traumatized to the point of refusing to cruise again while others threatened a class action lawsuit. The ship's late arrival cut the following 14-day cruise short by one day.[52][53][54]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to January 2018 North American blizzard. |

- 2017–18 North American cold wave – affected the United States at the same time

- 2017–18 North American winter

- Early January 2014 nor'easter – similar system that impacted the Northeastern United States around the same time frame four years earlier

- March 2014 nor'easter – A comparably powerful storm that impacted the United States East Coast and Eastern Canada

- Early February 2013 North American blizzard – powerful blizzard that formed and took a track in a similar matter to the nor'easter.

- March 2017 North American blizzard – significant winter storm that impacted much of the Northeastern United States nearly a year prior

References

- Gallina, Gregg (January 4, 2018). "Storm Summary Number 6 for Eastern U.S. Coastal Winter Storm". Storm Summary Message. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Benfield, Aon. "Global Catastrophe Recap - May 2018" (PDF). Aon Benfield. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- Samenow, Jason (January 4, 2018). "Historic 'bomb cyclone' unleashes blizzard conditions from coastal Virginia to New England. Frigid air to follow". Washington Post. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Petersen, Daniel (January 1, 2018). "Probabilistic Heavy Snow and Icing Discussion 08:17Z January 1, 2018". Winter Weather Forecast Discussion. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Musher, Michael (January 2, 2018). "Probabilistic Heavy Snow and Icing Discussion 21:45Z January 2, 2018". Winter Weather Forecast Discussion. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Pereira, Frank (January 1, 2018). "Probabilistic Heavy Snow and Icing Discussion 21:16Z January 1, 2018". Winter Weather Forecast Discussion. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Petersen, Daniel (January 1, 2018). "Probabilistic Heavy Snow and Icing Discussion 08:39Z January 1, 2018". Winter Weather Forecast Discussion. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Jewell, Ryan (January 3, 2018). "Mesoscale Discussion 1". Storm Prediction Center. Norman, Oklahoma: National Weather Service. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Musher, Michael (January 3, 2018). "Probabilistic Heavy Snow and Icing Discussion 21:21Z January 3, 2018". Winter Weather Forecast Discussion. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Hamrick, David (January 3, 2018). "Storm Summary Number 1 for Eastern U.S. Coastal Winter Storm". Storm Summary Message. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Tate, Jennifer (January 3, 2018). "Storm Summary Number 2 for Eastern U.S. Coastal Winter Storm". Storm Summary Message. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Samenow, Jason (January 4, 2017). "Historic 'bomb cyclone' unleashes blizzard conditions from coastal Virginia to New England. Frigid air to follow". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- Kong, Kwan-Yin (January 4, 2018). "Storm Summary Number 4 for Eastern U.S. Coastal Winter Storm". Storm Summary Message. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Sneed, Annie (January 3, 2018). "What Is This "Bomb Cyclone" Threatening the U.S.?" (Edited interview transcript). Scientific American. Nature America, Inc. Scientific American. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Jewell, Ryan (January 4, 2018). "Mesoscale Discussion 5". Storm Prediction Center. Norman, Oklahoma: National Weather Service. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Peters, Jeff; Karstens, Chris (January 4, 2018). "Mesoscale Discussion 6". Storm Prediction Center. Norman, Oklahoma: National Weather Service. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Karstens, Chris (January 4, 2018). "Mesoscale Discussion 8". Storm Prediction Center. Norman, Oklahoma: National Weather Service. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Peters, Jeff; Karstens, Chris (January 4, 2018). "Mesoscale Discussion 7". Storm Prediction Center. Norman, Oklahoma: National Weather Service. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Kong, Kwan-Yin (January 4, 2018). "Storm Summary Number 5 for Eastern U.S. Coastal Winter Storm". Storm Summary Message. College Park, Maryland: National Weather Service's Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Allen, Karma; Golembo, Max; Griffin, Melissa. "At least 6 dead as monster 'bomb cyclone,' thundersnow wallop Northeast". ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. ABC News. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Insurers brace for coastal flood losses from US 'bomb cyclone'". Insurance Day. January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- Teproff, Carli (January 2, 2018). "Some lucky students in Florida will be getting 'snow days' due to winter blast". Miami Herald. Miami, Florida: Miami Herald. Miami Herald. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Bynum, Russ (January 3, 2018). "Florida, Southeast seaboard hit by frosty storm". The Mercury News. Savannah, Georgia: Digital First Media. Associated Press. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Ellen Klas, Mary (January 3, 2018). "It's snowing in Tallahassee for the first time in three decades". Miami Herald. Tallahassee, Florida: Miami Herald. Herald/Times Tallahassee Bureau. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Shayanian, Sara; Haynes, Danielle (January 3, 2018). "Winter storm brings snow to Florida, closes southern airports". United Press International, Inc. United Press International. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- "Winter Storm Grayson Southeast Recap: Snow and Ice From North Florida to the Eastern Carolinas". The Weather Company. The Weather Channel. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Breslin, Sean (January 3, 2018). "Emergencies Declared in North Carolina, Virginia as Winter Storm Grayson Moves North". The Weather Company, LLC. The Weather Channel. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Micolucci, Vic; Stacey, Jonathan (January 3, 2018). "Winter storm leaves thousands without power in NE Florida, SE Georgia". Jacksonville, Florida: News4Jax.com. News4Jax. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Avanier, Erik (January 3, 2018). "Nassau County opens shelter due to power outages in Hilliard area". Hilliard, Florida: News4Jax.com. News4Jax. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Patrick, Steve (January 3, 2018). "Cold weather shelters open in Baker, Duval & Nassau counties". Jacksonville, Florida: News4Jax.com. News4Jax. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Torralva, Krista. "Coldest air in years set to blast Florida". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando, Florida: Orlando Sentinel. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Henning, Allyson; Harding, Ashley (January 3, 2018). "Snow, ice close some bridges in Georgia, I-10 reopens in Florida". Jacksonville, Florida: News4Jax.com. News4Jax. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- "Dangerous travel conditions, power outages caused by snow and ice cripple coastal South Carolina". The Post and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina: Post and Courier. The Post and Courier. January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Krueger, Nick (January 4, 2018). "Gov. Henry McMaster authorizes SC National Guard resources for winter storm recovery". Live 5 News. Charleston, South Carolina: Raycom Media. WCSC-TV. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Jackson, Angie (January 5, 2018). "Some snow from historic winter storm turns to slush, but Lowcountry conditions remain icy and dicey". The Post and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina: Post and Courier. The Post and Courier. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Exec. Order No. 2018-31 (January 3, 2018; in English) Governor of North Carolina. Retrieved on January 4, 2018.

- Bonner, Lynn; Moody, Aaron (January 4, 2018). "Four dead in North Carolina after winter storm". The News & Observer. Raleigh, North Carolina: Newsobserver.com. The News & Observer. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Waggoner, Martha; Drew, Jonathan (January 4, 2018). "Coastal North Carolina counties walloped by snow storm". Houston Chronicle. Raleigh, North Carolina: Hearst Newspapers, LLC. Associated Press. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Coy, Brian (January 3, 2018). "Governor McAuliffe Declares State of Emergency in Response to Impending Winter Storm" (Press release). Richmond, Virginia: Commonwealth of Virginia. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- "Icy roads will be major problem Thursday night into Friday". Hampton Roads, Virginia: WAVY.com. WAVY-TV. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Winter storm results in 382 crashes, 409 disabled vehicle incidents in Va., Md. area". Washington, D.C.: Sinclair Broadcast Group. WJLA-TV. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Winter storm brings blizzard conditions to Hampton Roads". Hampton Roads, Virginia: WAVY.com. WAVY-TV. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Dance, Scott (January 4, 2018). "Baltimore records one of lowest tides in decades amid 'bomb cyclone' winds". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimoresun.com. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Coast Guard: No ships to enter Baltimore port ahead of storm". The Washington Post. Baltimore, Maryland: The Washington Post. Associated Press. January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Samenow, Jason. "Historic 'bomb cyclone' unleashes blizzard conditions from coastal Virginia to New England. Frigid air to follow". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- "'Bomb Cyclone' Pummels Northeast, Whipping the East Coast With Snow and Bitter Cold". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- "NWS Boston storm summary PNS". Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Libon, Daniel. "Snowstorm Flooding Approaching Blizzard Of '78 Territory". Patch Staff. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- "'Bomb Cyclone' Pummels Northeast, Whipping the East Coast With Snow and Bitter Cold". The New York Times. New York City, New York: The New York Times Company. The New York Times. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Inc., Pelmorex Weather Networks. "Hurricane force winds, 50+ cm of snow slams the Maritimes". The Weather Network. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Owain Johnston-Barnes (January 5, 2018). "Storm Grayson blamed for poor weather | The Royal Gazette:Bermuda News - Mobile". Mobile.royalgazette.com. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ""It was hell for me": Woman recalls cruise ship ride during "bomb cyclone"". CBS News. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Norwegian Cruise Sailed Through Thick Of Winter Storm « CBS New York". Newyork.cbslocal.com. January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Norwegian Cruise Line passengers on ship that sailed through 'bomb cyclone' describe 'nightmare' ride". Fox News. January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.