Live Oak, Florida

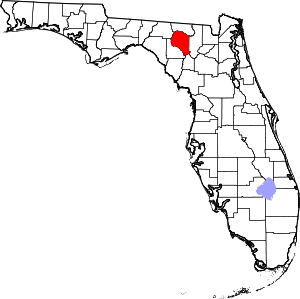

Live Oak is a city in Suwannee County, Florida, United States. The city is the county seat of Suwannee County[5] and is located east of Tallahassee. As of 2010, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 6,850.

Live Oak, Florida | |

|---|---|

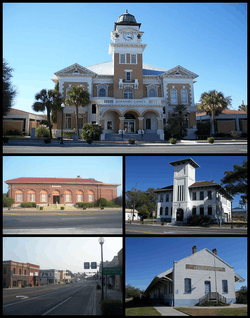

Suwannee County Courthouse, Old Post Office, Old Live Oak City Hall, Downtown Live Oak, ACL Freight Station | |

| Nickname(s): The city of nature | |

| Motto(s): "A Caring Community " | |

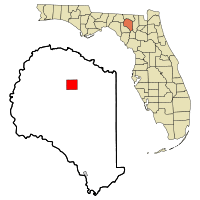

Location in Suwannee County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 30°17′40″N 82°59′9″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Suwannee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.63 sq mi (19.76 km2) |

| • Land | 7.63 sq mi (19.76 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 105 ft (32 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,850 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 6,972 |

| • Density | 913.88/sq mi (352.87/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 32060, 32064 |

| Area code(s) | 386 |

| FIPS code | 12-40875[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0285862[4] |

| Website | www.cityofliveoak.org |

U.S. Highway 90, U.S. Highway 129 and Interstate 10 are major highways running through Live Oak.

Freight service is provided by the Florida Gulf & Atlantic Railroad, which acquired most of the former CSX main line from Pensacola to Jacksonville on June 1, 2019.

It is served by the Suwannee County Airport as well as many private airparks scattered throughout the county.

There is also a community named Live Oak in Washington County, Florida.

History

Built along the Pensacola & Georgia Railroad in or prior to 1861, Live Oak was named for a southern live oak tree under which railroad workers rested and ate lunch. When a railroad depot was built nearby, the small community that sprung up around it was called “Live Oak Station” (first mentioned in records in 1861). The tree was located where the now-present Pepe's Mexican Grocery on U.S. 90 is located.[6]

During the Civil War, the Pensacola & Georgia Railroad served as a vital route for parts of North Florida, and earthworks were built where it crossed the Suwannee River west of Live Oak, to deter Union attacks; these earthworks still exist as part of the Suwannee River State Park, one of Florida's first State parks. In order to ease the supply problem into other parts of the Confederacy, the Confederate government decided to create a north–south railroad link into Georgia through Live Oak. The railroad junction was completed in early 1865, too late to help the Confederacy, but it opened up the interior of the county to settlement after the Civil War.

Live Oak became the county seat of Suwannee County in 1868. An election held the following year confirmed Live Oak as the county seat, and it has remained such ever since.

Live Oak was incorporated as a town in 1878. In 1903, it became a city and was the largest community in Suwannee County, serving as a minor railroad hub for the region.

In the 1905 State census, Live Oak was the largest inland, and fifth-largest overall, city in Florida (behind Jacksonville, Pensacola, Tampa, and Key West, in that order). Nearby resorts at Suwannee Springs and Dowling Park (formerly Hudson-upon-the-Suwannee) drew thousands of visitors from around the world to the sulphur springs and related nearby sports, boating, and hunting activities. The health benefits of the springs were touted in magazines and newspapers worldwide, supposedly.curing everything from arthritis to “female problems”.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, Live Oak saw a construction boom. Notable buildings such as the Suwannee County Courthouse, Live Oak City Hall, and Suwannee Hotel were completed, and dozens of fine two- and three-story homes were erected along the major streets. By 1913, the main streets were bricked and a sewage system had been built.

Live Oak soon after lost status relative to explosive south Florida growth and the realization that the sulphur waters did nothing to combat various illnesses. Devastation of the cotton crop by the boll weevil near the end of the First World War nearly finished off the city and county as an economic powerhouse, and business stagnated with the coming of the Great Depression. Politically, Live Oak and Suwannee County remained powerful for another four decades until redistricting took into account the massive growth of southern Florida.

Ruby Strickland, former postmistress of the community of Dowling Park, became mayor of Live Oak in 1924. She was the first female elected as mayor south of the Mason-Dixon Line after universal suffrage was enacted in 1919. Mrs. Strickland served two non-consecutive terms and represented the area at the Democratic National Convention of 1936.

In 1940, the men of the local National Guard unit, Company E of the 124th Infantry (historically called the Suwannee Rifles), were mustered into service for one year of training at Camp Blanding, Florida. A week after the December 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the unit was assigned to the 31st Division at Fort Benning, Georgia, to serve as a model infantry training unit. The unit was briefly deactivated in 1944, but reactivated the following month after many of the original men had been dispersed to other units; members served in both the European and Pacific theatres during World War II. Florida National Guard historian Robert Hawk noted that, “In the course of the Second World War, no unit of the Florida National Guard had more men killed, wounded in action, or dead from other causes than Company E, 124th Infantry.” The Live Oak unit was reorganized several times over the years as infantry, tank, and engineering companies, and now (2019) serves as the 868th Engineer Company. The unit has purportedly been called up to serve more than any other unit in Florida.

In 1944, African American Willie James Howard was lynched in Live Oak for having "expressed his affections" to a white girl. He was subsequently murdered by the girl's father, former state legislator A.P. "Phil" Goff, who kidnapped Howard, bound him, and forced him to jump off a bridge. A Sewanee County grand jury failed to indict Goff. Media attention in Live Oak in the aftermath of he death of Willie James Howard would increase awareness of lynching in the United States.

In 1948, Live Oak and Suwannee County received their first real public hospital, completed under the Hill-Burton Act that provided Federal funding for health care facilities to rural areas. The Suwannee County Hospital served the citizens of the region until being replaced in the early 1990s.

In 1952, national attention was drawn to Live Oak and Suwannee County when a wealthy African American, Ruby McCollum, shot and killed Dr. Clifford Leroy Adams, Jr., a prominent, recently-elected State legislator, in his office across from the Suwannee County Courthouse. Originally thought to be a murder based upon an unpaid doctor's bill, it was soon revealed that the married Dr. Adams had fathered a child with Ruby (whose husband Sam oversaw the illegal “bolita” gaming). Ruby's murder conviction was overturned on a technicality in 1954 and she spent the next twenty years in the Florida State Mental Hospital in Chattahoochee after having been deemed mentally unfit to stand trial a second time. The murder and events surrounding it have become the source of many books and documentaries.

In the 1950s, the rest of Suwannee County received electricity and telephone service, something the City of Live Oak had since the late 1800s. In 1957, the Florida Sheriffs Association received property north of Live Oak for use as a Boys’ Ranch. Opening in 1958, this facility has continued to be used to help troubled boys from all of Florida; later, a Girls’ Ranch and Youth Villa were constructed in other parts of the state for girls and sibling groups.

In September 1964, Hurricane Dora dumped massive amounts of water on Live Oak, flooding major intersections and leaving the downtown area partially submerged. The damage led to the abandonment or tearing down of several historic buildings and the relocation of other businesses to higher ground.

In 1983, the Suwannee County Development Authority opened a park north of Live Oak along the banks of the Suwannee River. This park was little developed until being sold to private individuals in the 1990s. Renamed the Spirit of the Suwannee Music Park, it hosts music festivals for all types of music, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors to Live Oak and Suwannee County annually.

Tropical Storm Debby (2012) surpassed the amount of rain brought by Hurricane Dora, and despite vastly improved drainage, much of Live Oak once again flooded. Interstates were shut down as portions were underwater, and much of the surrounding area was cut off from the outside world. In addition, dozens of sinkholes, some quite large, opened up all over the city and county, causing further damage. Several downtown buildings that were more than 100 years old were impacted and later torn down, replaced by public parks for community events.

Live Oak remains the largest community and only full-fledged city in Suwannee County. Eco-tourism in and around Live Oak brings thousands of people from all over the country to places such as the nearby Spirit of the Suwannee Music Park, the Suwannee River State Park, and numerous springs along the famed Suwannee River. In addition, agriculture-related business (including timber, pine straw, and watermelons) is still the dominant industry in Suwannee County, with international companies like Klausner Lumber making their home in and around Live Oak.

Geography

Geographically, Suwannee County is situated on a limestone bed riddled with underground freshwater streams, which surface in dozens of beautiful springs. This phenomenon of "Karst topography" gives the area a local supply of renewable fresh water and abundant sources of fishing. The county is known as a world-class cave diving site for SCUBA enthusiasts, and underwater cave explorer Sheck Exley chose to live here in order to have close access to many of the springs.

Fishing sites include a number of small lakes about 5 miles east of the town. Suwannee Lake is the most well stocked and notable, but there is also Workman Lake, Dexter Lake, Campground Lake, Little Lake Hull, White Lake, Tiger Lake, Bachelor Lake, and Peacock Lake.[7]

The Twin Rivers State Forest is a 14,882-acre (60 km2) Florida State forest located in North Central Florida, near Live Oak.[8]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 458 | — | |

| 1890 | 687 | 50.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,659 | 141.5% | |

| 1910 | 3,450 | 108.0% | |

| 1920 | 3,103 | −10.1% | |

| 1930 | 2,734 | −11.9% | |

| 1940 | 3,427 | 25.3% | |

| 1950 | 4,064 | 18.6% | |

| 1960 | 6,544 | 61.0% | |

| 1970 | 6,830 | 4.4% | |

| 1980 | 6,732 | −1.4% | |

| 1990 | 6,332 | −5.9% | |

| 2000 | 6,480 | 2.3% | |

| 2010 | 6,850 | 5.7% | |

| Est. 2019 | 6,972 | [2] | 1.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2011, there were 6,918 people, 2,361 households, and 1,562 families residing in the city. The population density was 931.7 per square mile (359.5/km2). There were 2,951 housing units at an average density of 904.6 per square mile (152.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 54.4% White, 35.0% African American, Hispanic or Latino of any race were 16.2% of the population. 0.25% Native American, 1.0% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 2.4% from other races, and 2.4% from two or more races.

There were 2,623 households, out of which 30.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.5% were married couples living together, 22.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.8% were non-families. 28.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.60 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.6% under the age of 18, 11.0% from 18 to 24, 24.1% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 18.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $24,380, and the median income for a family was $29,099. Males had a median income of $22,403 versus $20,154 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,374. About 19.6% of families and 23.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.9% of those under age 18 and 20.9% of those age 65 or over.

Climate

Live Oak receives rain, on average, 84 days per year. This makes it the city that receives the fewest days of rain per year over 0.1 inches in Florida.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Live Oak, Florida" Archived 2013-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, See North Florida website

- Larry Kinder, Flyfisher's Guide to Freshwater Florida, p. 206, Wilderness Adventures Press, 2003 ISBN 1885106971.

- "Twin Rivers State Forest". Florida Forest Service. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Live Oak, Florida. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Live Oak. |

Suwannee Valley Times is a free newspaper http://www.suwanneevalleytimes.com/

- Live Oak Daily Democrat Historical newspaper for Live Oak, Florida fully and openly available in the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- City of Live Oak City website

- Suwannee Democrat Current newspaper of record for Live Oak