Jan Henryk Dąbrowski

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (Polish pronunciation: [ˈjan ˈxɛnrɨɡ dɔmˈbrɔfskʲi]; also known as Johann Heinrich Dąbrowski (Dombrowski)[5] in German[6] and Jean Henri Dombrowski in French;[7] 29 August 1755[lower-alpha 1] – 6 June 1818) was a Polish general and statesman, widely respected after his death for his patriotic attitude, and described as a national hero.[8]

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski | |

|---|---|

| Born | 29 August 1755[lower-alpha 1] Pierzchów, Poland |

| Died | 6 June 1818 (aged 62) Winna Góra, Posen, Prussia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Cavalry |

| Years of service | 1770–1816 |

| Rank | General of Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | Kościuszko Uprising War of the Second Coalition Battle of Trebbia Battle of Friedland Russian Campaign Battle of Leipzig |

| Awards | Order of Virtuti Militari[1] Order of the White Eagle[2] Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour[3] Order of the Iron Crown[3] Order of St. Vladimir[4] Order of St. Anna[4] |

| Other work | Senator of Congress Poland |

| Signature | |

Dąbrowski initially served in the Saxon Army and joined the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Army in 1792, shortly before the Second Partition of Poland. He was promoted to the rank of general in the Kościuszko Uprising of 1794. After the final Third Partition of Poland, which ended the existence of Poland as an independent country, he became actively involved in promoting the cause of Polish independence abroad. He was the founder of the Polish Legions in Italy serving under Napoleon from 1795, and as a general in Italian and French service he contributed to the brief restoration of the Polish state during the Greater Poland Uprising of 1806. He participated in the Napoleonic Wars, taking part in the Polish-Austrian war and the French invasion of Russia until 1813. After Napoleon's defeat, he accepted a senatorial position in the Russian-backed Congress Poland, and was one of the organizers of the Army of Congress Poland.

The Polish national anthem, "Poland Is Not Yet Lost", written and first sung by the Polish legionnaires, mentions Dąbrowski by name, and is also known as "Dąbrowski's Mazurka".[9]

Early life and education

In Saxony and Poland

Dąbrowski was born to Jan Michał Dąbrowski and Zofia Maria Dąbrowska, née Sophie von Lettow,[10] in Pierzchów, Crown of the Kingdom of Poland,[9] on 29 August 1755.[lower-alpha 1] He grew up in Hoyerswerda, Electorate of Saxony, where his father served as a Colonel in the Saxon Army.[13] He joined the Royal Saxon Horse Guards in 1770[14][15] or 1771.[6][16] His family was of Polish origin.[11] Nonetheless, in his childhood and youth he grew up surrounded by German culture in Saxony, and signed his name as Johann Heinrich Dąbrowski.[6] He fought in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–1779), during which time his father died.[6] Shortly afterwards in 1780 he married Gustawa Rackel.[6] He lived in Dresden, and steadily progressed through the ranks, becoming a Rittmeister in 1789.[6] He served as Adjutant general of King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, from 1788 to 1791.[17]

Career

Following the appeal of the Polish Four-Year Sejm to all Poles serving abroad to join the Polish army, and not seeing much opportunity to advance in his military career in the now-peaceful Saxony, on 28 June 1792, Dąbrowski joined the Army of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with a rank of podpułkownik and on 14 July he was promoted to the rank of vice-brigadier.[6] Joining in the final weeks of the Polish–Russian War of 1792, he did not see combat in it.[6] Unfamiliar with the intricacies of Polish politics, like many of Poniatowski's supporters, he joined the Targowica Confederation in late 1792.[6][18]

Dąbrowski was seen as a cavalry expert, and King Stanisław August Poniatowski was personally interested in obtaining Dąbrowski's services.[6] As a cavalryman educated in a Dresden military school under Count Maurice Bellegarde, a reformer of the Saxon army's cavalry, Dąbrowski was asked to help modernize the Polish cavalry, serving in the ranks of the 1st Greater Poland Cavalry Brigade (1 Wielkpolska Brygada Kawalerii Narodowej).[6] In January 1793, stationed around Gniezno with two units of cavalry, about 200 strong, he briefly engaged the Prussian forces entering Poland in the aftermath of the Second Partition of Poland, and afterwards became a known activist, advocating the continuation of military struggle against the occupiers.[6][19]

The Grodno Sejm, held in the fall of 1793, nominated him for a membership in a military commission; this caused him to be viewed with suspicion by the majority of the dissatisfied military, and he was not included in the preparations for the upcoming uprising.[20] Thus he was taken by surprise when the Kościuszko Insurrection erupted, and his own brigade mutinied.[20] He declared his support for the insurgents after the liberation of Warsaw, and from then on took an active part in the uprising, defending Warsaw and leading an army corps in support of an uprising in Greater Poland.[16][20] His courage was commended by Tadeusz Kościuszko himself, the Supreme Commander of the National Armed Forces, who promoted him to the rank of general.[20]

In the Napoleonic service

After the failure of the uprising he remained in partitioned Poland for a while, attempting to convince the Prussian authorities that they needed Poland as an ally against Austria and Russia.[16] He was unsuccessful, and with the Third Partition of Poland between Russia, Prussia and Austria, Poland disappeared from the map of Europe. Dąbrowski's next solution was to convince the French Republic that it should support a Polish cause, and create a Polish military formation.[16] This proved to be more successful, and indeed Dąbrowski is remembered in the history of Poland as the organiser of Polish Legions in Italy during the Napoleonic Wars. (These Legions are also often known as the "Dąbrowski's Legions".)[16][21] This event gave hope to contemporary Poles, and is still remembered in the Polish national anthem, named after Dąbrowski.[9] He began his work in 1796, when he came to Paris and soon afterwards met Napoleon Bonaparte in Milan.[22] On January 7, 1797, he was authorized by the Cisalpine Republic to create Polish legions, which would be part of the army of the newly created Republic of Lombardy.[16][22]

In April, Dąbrowski lobbied for a plan to push through to the Polish territories in Galicia, but that was blocked by Napoleon who instead decided to use those troops on the Italian front.[23] Dąbrowski's Polish soldiers fought at Napoleon's side from May 1797 until the beginning of 1803. As a commander of his legion he played an important part in the war in Italy, entered Rome in May 1798, and distinguished himself greatly at the Battle of Trebia on June 19, 1799, where he was wounded, as well as in other battles and combats of 1799–1801.[22] From the time the Legions garrisoned Rome, Dąbrowski obtained a number of trophies from a Roman representative, namely the ones that the Polish king, Jan III Sobieski, had sent there after his victory over the Ottoman Empire at the siege of Vienna in 1683; amongst these was an Ottoman standard which subsequently became part of the Legions' colors, accompanying them from then on.[24][25] However, the legions were never able to reach Poland and did not liberate the country, as Dąbrowski had dreamed. Napoleon did, however, notice the growing dissatisfaction of his soldiers and their commanders. They were particularly disappointed by a peace treaty between France and Russia signed in Lunéville on 9 February 1801, which dashed Polish hopes of Bonaparte freeing Poland.[21][22] Shortly afterwards, in March, Dąbrowski reorganized both Legions at Milan into two 6,000-strong units.[26] Disillusioned with Napoleon after the Lunéville treaty, many legionnaires resigned afterwards; of the others, thousands perished when the Legions were sent to suppress the Haitian Revolution in 1803; by that time Dąbrowski was no longer in command of the Legions.[22]

Dąbrowski, meanwhile, spent the first few years of the new century as a general in the service of the Italian republic.[22] In 1804 he received the Officer cross of Legion of Honour, and the next year, the Italian Order of the Iron Crown.[27] Together with Józef Wybicki he was summoned again by Napoleon in fall of 1806 and tasked with recreating the Polish formation, which Napoleon wanted to use to recapture Greater Poland from Prussia.[28] The ensuing conflict was known as the Greater Poland Uprising, and Dabrowski was the chief leader of Polish insurgent forces in it.[16] Dąbrowski distinguished himself at siege of Tczew, siege of Gdańsk and at Battle of Friedland.[28]

In 1807, the Duchy of Warsaw was established in the recaptured territories, essentially as a satellite of Bonaparte's France. Dąbrowski became disappointed with Napoleon, who offered him monetary rewards, but no serious military or government position.[28] He was also awarded the Virtuti Militari medal that year.[1] In 1809, he set out to defend Poland against an Austrian invasion under the command of Prince Józef Poniatowski.[28] Joining the Army of the Duchy of Warsaw shortly after the Battle of Raszyn, he took part in the first stages of the offensive on Galicia, and then organized the defense of Greater Poland.[28] In June 1812, Dąbrowski commanded the 17th (Polish) Infantry Division in the V Corps of the Grande Armée, during Napoleon's invasion of Russia.[16][28] However, by October the Franco-Russian war was over and the French forces, decimated by a severe winter, had to retreat. At the disastrous Battle of Berezina in late November that year, Dąbrowski was wounded, and his leadership and tactics in it were criticized.[2][28] After the March reorganization of the Grande Armée, he commanded the 27th (Polish) Infantry Division in the VIII Corps.[29] He commanded it at the Battle of Leipzig (1813), and subsequently on 28 October he became the commander in chief of the all remaining Polish forces in Napoleon's service, succeeding Antoni Paweł Sułkowski.[2]

Final years

Dąbrowski always associated independent Poland with a Polish Army, and offered his services to the new power, which promised to organize such a formation: Russia.[2] He was one of the generals entrusted by the Tsar Alexander of Russia with the reorganization of the Duchy's army into the Army of Congress Poland.[16] In 1815 he received the titles of general of cavalry and senator-voivode of the new Congress Kingdom.[9] He was also awarded the Order of the White Eagle on December 9 that year.[2] Soon afterward he withdrew from active politics.[16] He retired in the following year to his estates in Winna Góra in the Grand Duchy of Posen, Kingdom of Prussia, where he died on 6 June 1818, from a combination of pneumonia and gangrene.[2] He was buried in the church in Winna Góra.[2]

Over the years, Dąbrowski wrote several military treatises, primarily about the Legions, in German, French and Polish.[2]

Remembrance

Dąbrowski was often criticized by his contemporaries, and by the early Polish historiography, but his image improved with time.[8][30][31] He has been often compared to the two other military heroes of the time of Partitions and the Legions, Tadeusz Kościuszko and Józef Poniatowski,[8] and to the father of the Second Polish Republic, Józef Piłsudski.[32] In particular, his mention in the Polish national anthem, also known as "Dąbrowski's Mazurek", contributed to his fame in Poland.[9][32] It is not uncommon for modern works of Polish history to describe him as a "(national) hero".[8]

Dąbrowski is also remembered outside of Poland for his historical contributions. His name, in the French version "Dombrowsky", is inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.[33]

See also

- History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–95)

- History of Poland (1795–1918)

Notes

References

- Gąsowski, Tomasz (1998). Wybitni Polacy XIX wieku: leksykon biograficzny (in Polish). Wydawn. Literackie. p. 96. ISBN 978-83-08-02839-1.

- Skałkowski, 1946, p. 5

- Capefigue, Baptiste H. R. (1842). L'Europe pendant le consulat et l'empire de Napoléon (in French). Wouters, Raspoet et Co. p. 241.

- Biographie des hommes vivants (in French). Paris. 1817. p. 409.

- Rüegg, Walter (2004). Geschichte der Universität in Europa (in German). C.H. Beck. p. 230. ISBN 3-406-36954-5.

- Skałkowski, 1946, p. 1

- Connelly, Owen (2006). Blundering to Glory. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 172.

Pivka, Otto. Napoleon's Polish troops. Osprey. p. 3. ISBN 0-85045-198-1.

Leggiere, Michael V. (2002). Napoleon and Berlin, The Franco-Prussian war in North Germany 1813. University of Oklahoma. p. 374. ISBN 0-8061-3399-6. - Rezler, Marek (1982). Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755–1818. Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. p. 3.

Generał Jan Henryk Dąbrowski należy do bohaterów narodowych otoczonych w polskim społeczeństwie szczególnym kultem.

- Sokol, Stanley S.; Mrotek Kissane, Sharon F.; Abramowicz, Alfred L. (1992). The Polish biographical dictionary: profiles of nearly 900 Poles who have made lasting contributions to world civilization. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 89. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- (in German)Der Spiegel, Die Gesellschaft auf -ki

- Rezler, Marek (1982). Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755-1818. Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. p. 4.

29 sierpnia 1755 roku w Pierzchowcu (d. powiat bocheński) urodził się chłopiec, któremu zgodnie z tradycją rodzinną nadano podwójne imię: Jan Henryk

- Zych, 1964, p. 55: "Tam to, 29 sierpnia 1755 r., przyszedł na świat Jan Henryk"

- Zeitgenossen: ein biographisches Magazin für d. Geschichte unserer Zeit. Brockhaus. 1830. pp. 5–.

- Conversations-Lexikon der neuesten Zeit und Literatur (in German). F. A. Brockhaus. 1832. p. 704.

- Bronikowski, Alexander (1827). Die Geschichte Polens (in German). Dresden: Hilscher. p. 135.

- Lerski, Jerzy Jan (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- Allgemeines deutsches Conversations-Lexikon für die Gebildeten eines jeden Standes (in German). Leipzig: Gebr. Reichenbach. 1840. p. 537.

- Zych, 1964, p. 55.

- Zych, 1964, p. 59

- Skałkowski, 1946, p. 2.

- Lerski, Jerzy Jan (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Skałkowski, 1946, p. 3

- Otto Von Pivka; Michael Roffe (15 June 1974). Napoleon's Polish Troops. Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-85045-198-6. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Kołaczkowski, Klemens (1901). Henryk Dąbrowski twórca legionów polskich we Włoszech, 1755–1818: wspomnienie historyczne (in Polish). Spółka Wydawnicza Polska. pp. 35–36. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Fletcher, James (1833). The history of Poland: from the earliest period to the present time. J. & J. Harper. p. 285. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Otto Von Pivka; Michael Roffe (15 June 1974). Napoleon's Polish Troops. Osprey Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-85045-198-6. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Mickiewicza, 1970, p. 27.

- Skałkowski, 1946, p. 4.

- Pachoński, Jan (1987). Generał Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755–1818. Wydawn. Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej. p. 463.

- Zych, 1964, p. 10

- Pachoński, Jan (1987). Generał Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755–1818. Wydawn. Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej. p. 7.

- Poznaniu, Muzeum Narodowe w (2005). Marsz, marsz Dąbrowski--: w 250. rocznicę urodzin Jana Henryka Dąbrowskiego. Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu. p. 37.

Jego pozycję w narodowym panteonie niewątpliwie ugruntowała Pieśń Legionów z nieśmiertelnym referenem "Marsz, marsz Dąbrowski...", która w odrodzonej Ojczyźnie uznano za hymn państwowy.

- Antemurale (in French). Institutum. 1972. p. 17.

Bibliography

- Adam Skałkowski (1939–1946). "Jan Henryk Dąbrowski". Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). V.

- Generał Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (1755–1818): Materiały z międzyuczelnianej sesji naukowej UAM iWAP odbytej w Poznaniu 28 III 1969. Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza. 1970.

- Zych, Gabriel (1964). Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755–1818 (in Polish). Wydawn. Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

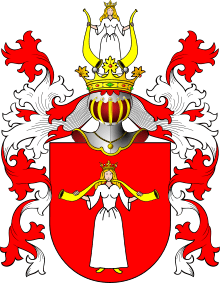

- "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" (Dąbrowski's Mazurka), the national anthem of Poland, with lyrics written by JÓZEF RUFIN WYBICKI herbu (coat of arms) Rogala in Reggio Emilia, Cisalpine Republic, Northern Italy, between 16 and 19 July 1797; The music is an unattributed (composer unknown) mazurka.