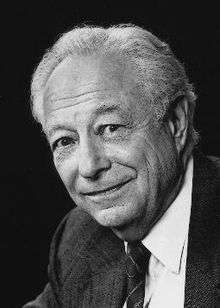

Irving Kristol

Irving Kristol (/ˈkrɪstəl/; January 22, 1920 – September 18, 2009) was an American journalist who was dubbed the "godfather of neoconservatism".[1][2] As a founder, editor, and contributor to various magazines, he played an influential role in the intellectual and political culture of the last half of the twentieth century.[3] After his death, he was described by The Daily Telegraph as being "perhaps the most consequential public intellectual of the latter half of the [twentieth] century".[4]

Irving Kristol | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 22, 1920 Brooklyn, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 18, 2009 (aged 89) Falls Church, Virginia, U.S. |

| Alma mater | City College of New York |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Spouse(s) | Gertrude Himmelfarb |

| Children | Elizabeth Nelson and William Kristol |

Life and career

Kristol was born in Brooklyn, New York, the son of non-observant Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Bessie (Mailman) and Joseph Kristol.[5][6] He received his B.A. from the City College of New York in 1940, where he majored in history and was part of a small, but vocal, Trotskyist anti-Soviet group who eventually became known as, The New York Intellectuals. It was at these meetings that Kristol met historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, whom he later married in 1942. They had two children, Elizabeth Nelson and Bill Kristol.[7] During World War II, he served in Europe in the 12th Armored Division as a combat infantryman.[8]

Kristol was affiliated with the Congress for Cultural Freedom. He wrote in Commentary magazine from 1947 to 1952 under the editor Elliot E. Cohen (not to be confused with Eliot A. Cohen, the writer of today's magazine). With Stephen Spender, he was co-founder of and contributor to the British-based Encounter from 1953 to 1958; editor of The Reporter from 1959 to 1960. He also was the executive vice-president of the publishing house, Basic Books, from 1961 to 1969, the Henry Luce Professor of Urban Values at New York University from 1969 to 1987, and co-founder and co-editor (first with Daniel Bell and then Nathan Glazer) of The Public Interest from 1965 to 2002. He was the founder and publisher of The National Interest from 1985 to 2002. Following Ramparts' publication of information showing Central Intelligence Agency funding of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which was widely reported elsewhere, Kristol left in the late 1960s and became affiliated with the American Enterprise Institute.[9]

Kristol was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute (having been an associate fellow from 1972, a senior fellow from 1977 and the John M. Olin Distinguished Fellow from 1988 to 1999). As a member of the board of contributors of The Wall Street Journal, he contributed a monthly column from 1972 to 1997. He served on the Council of the National Endowment for the Humanities from 1972 to 1977.

In 1978, Kristol and William E. Simon founded The Institute For Education Affairs, which as a result of a merger with the Madison Center became the Madison Center for Educational Affairs in 1990.

In July 2002, he received from President George W. Bush the Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

Kristol died from complications of lung cancer, aged 89, on September 18, 2009 at the Capital Hospice in Falls Church, Virginia.[1][10]

Ideas

During the late 1960s up until the 1970s, neoconservatives were worried about the Cold War and that its liberalism was turning into radicalism, thus many neoconservatives including Irving Kristol, Norman Podhoretz and Daniel Patrick Moynihan wanted Democrats to continue on a strong anti-communist foreign policy.[11] This foreign policy was to use Soviet human rights violations to attack the Soviet Union.[11] This later led to Nixon's policies called détente.[11]

In 1973, Michael Harrington coined the term, "neo-conservatism", to describe those liberal intellectuals and political philosophers who were disaffected with the political and cultural attitudes dominating the Democratic Party and were moving toward a new form of conservatism.[12] Intended by Harrington as a pejorative term, it was accepted by Kristol as an apt description of the ideas and policies exemplified by The Public Interest. Unlike liberals, for example, neo-conservatives rejected most of the Great Society programs sponsored by Lyndon B. Johnson and, unlike traditional conservatives, they supported the more limited welfare state instituted by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In February 1979, Kristol was featured on the cover of Esquire. The caption identified him as "the godfather of the most powerful new political force in America – Neo-conservatism".[13] That year also saw the publication of the book, The Neo-conservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America's Politics. Like Harrington, the author, Peter Steinfels, was critical of neo-conservatism, but he was impressed by its growing political and intellectual influence. Kristol's response appeared under the title "Confessions of a True, Self-Confessed – Perhaps the Only – 'Neo-conservative'".[14]

Neo-conservatism, Kristol maintained, is not an ideology but a "persuasion", a way of thinking about politics rather than a compendium of principles and axioms.[15] It is classical, rather than romantic, in temperament and practical and anti-utopian in policy. One of Kristol's most celebrated quips defines a neo-conservative as "a liberal who has been mugged by reality". These concepts lie at the core of neo-conservative philosophy to this day.[16]

That reality, for Kristol, is a complex one. While propounding the virtues of supply-side economics as the basis for the economic growth that is "a sine qua non for the survival of a modern democracy", he also insists that any economic philosophy has to be enlarged by "political philosophy, moral philosophy, and even religious thought", which were as much the sine qua non for a modern democracy.[17]

One of his early books, Two Cheers for Capitalism, asserts that capitalism, or more precisely, bourgeois capitalism, is worthy of two cheers. One cheer because "it works, in a quite simple, material sense" by improving the conditions of people; and a second cheer because it is "congenial to a large measure of personal liberty". He argues these are no small achievements and only capitalism has proved capable of providing them. However, it also imposes a great "psychic burden" upon the individual and the social order. Because it does not meet the individual's "'existential' human needs", it creates a "spiritual malaise" that threatens the legitimacy of that social order. As much as anything else, it is the withholding of that potential third cheer that is the distinctive mark of neo-conservatism as Kristol understood it.[18]

Articles

- “Other People's Nerve” (as William Ferry), Enquiry, May 1943.

- “James Burnham's 'The Machiavellians'" (as William Ferry), Enquiry, July 1943. (A review of The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom by James Burnham.)

- “Koestler: A Note on Confusion,” Politics, May 1944.

- “The Indefatigable Fabian,” New York Times Book Review, August 24, 1952. (A review of Beatrice Webb's Diaries: 1912–1924, edited by Margaret I. Cole.)

- "Men and Ideas: Niccolo Machiavelli," Encounter, December 1954.

- "American Intellectuals and Foreign Policy," Foreign Affairs, July 1967 (repr. in On the Democratic Idea in America).

- "Memoirs of a Cold Warrior," New York Times Magazine, February 11, 1968 (repr. in Reflections of a Neo-conservative).

- "When Virtue Loses All Her Loveliness," The Public Interest, Fall 1970 (repr. in On the Democratic Idea in America and Two Cheers for Capitalism).

- "Pornography, Obscenity, and Censorship," New York Times Magazine, March 28, 1971 (repr. in On the Democratic Idea in America and Reflections of a Neo-conservative).

- "Utopianism, Ancient and Modern," Imprimus, April 1973 (repr. in Two Cheers for Capitalism).

- "Adam Smith and the Spirit of Capitalism," The Great Ideas Today, ed. Robert Hutchins and Mortimer Adler, 1976 (repr. in Reflections of a Neo-conservative).

- "Memoirs of a Trotskyist," New York Times Magazine, January 23, 1977 (repr. in Reflections of a Neo-conservative).

- "The Adversary Culture of Intellectuals," Encounter, October 1979 (repr. in Reflections of a Neo-conservative).

- "The Hidden Cost of Regulation", The Wall Street Journal.

Books

Authored

- On the Democratic Idea in America. New York: Harper, 1972. ISBN 0060124679

- Two Cheers for Capitalism. 1978. ISBN 0465088031

- Reflections of a Neo-conservative: Looking Back, Looking Ahead. 1983. ISBN 0465068723

- Neo-conservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea. 1995. ISBN 0-02-874021-1

- The Neo-conservative Persuasion: Selected Essays, 1942-2009. New York: Basic Books, 2011. ISBN 0465022235

- On Jews and Judaism. Barnes & Noble, 2014.

Edited

- The Crisis in Economic Theory. Edited with Daniel Bell. New York: Basic Books, 1981.

Contributed

- ”Rationalism in Economics” (Chapter 12). The Crisis in Economic Theory. Edited with Daniel Bell. New York: Basic Books, 1981. p. 201.

See also

- Gertrude Himmelfarb

- William Kristol

- Norman Podhoretz

References

- Barry Gewen (September 18, 2009). "Irving Kristol, Godfather of Modern Conservatism, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- See, for example, http://www.reason.com/news/show/34900.html

- See, for example, "American Conservative Opinion Leaders," by Mark J. Rozell and James F. Pontuso, 1990.

- Stelzer, Irwin. Irving Kristol's gone – we'll miss his clear vision Telegraph.

- Hoeveler, J. David, Watch on the right: conservative intellectuals in the Reagan era (University of Wisconsin Press, 1991), ISBN 978-0-299-12810-4, p. 81

- Almanac, World (September 1986). The Celebrity who's who. ISBN 9780345339904.

- "Biography".

- Kristol, Irving. Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea. New York: The Free Press, 1995. ISBN 0-02-874021-1 pp. 3–4

- Saunders, Frances Stonor: The Cultural Cold War, page 419. The New Press,1999.

- "Irving Kristol, Architect of Neoconservatism, Dies at 89". washingtonpost.com. September 18, 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- The human rights revolution : an international history. Iriye, Akira., Goedde, Petra, 1964-, Hitchcock, William I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2012. ISBN 9780195333145. OCLC 720260159.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Lind, Michael, "A Tragedy of Errors", http://www.thenation.com/article/tragedy-errors Accessed 14 October 2010, The Nation, February 8, 2004

- dtmagazine.com Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Goldberg, Jonah, "The Neo-conservative Invention", http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/206955/neoconservative-invention/jonah-goldberg National Review Online, May 20, 2003

- Reflections of a Neo-conservative, p. 79

- Blumenthal, Sidney, "Mugged by reality", http://www.salon.com/news/opinion/blumenthal/2006/12/14/jeane_kirkpatrick/ Salon, December 14, 2006

- Neo-conservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea (New York, 1995), p. 37.

- Two Cheers for Capitalism (New York, 1978), pp. x–xii.

External links

- Website and bibliography of Irving Kristol's writings

- American Conservatism 1945–1995, by Irving Kristol

- On The Political Stupidity of the Jews, by Irving Kristol

- The Neoconservative Persuasion, by Irving Kristol

- Irving Kristol – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Irving Kristol Papers – Wisconsin Historical Society

- Booknotes interview with Kristol on Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea, September 24, 1995.

- Arguing the World, 1998 PBS documentary film featuring Nathan Glazer, Daniel Bell, Irving Howe, and Kristol