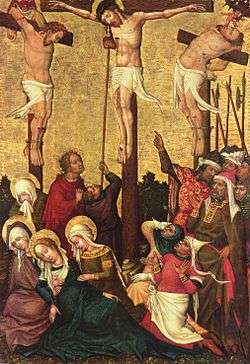

Impenitent thief

The impenitent thief is a man described in the New Testament account of the Crucifixion of Jesus. In the Gospel narrative, two criminal bandits are crucified alongside Jesus. In the Gospels of Mark and Matthew, they both join the crowd in mocking him. In the version of the Gospel of Luke, however, one taunts Jesus about not saving himself, and the other (known as the penitent thief) asks for mercy.[1][2][3]

In apocryphal writings, the impenitent thief is given the name Gestas, which first appears in the Gospel of Nicodemus, while his companion is called Dismas. Christian tradition holds that Gestas was on the cross to the left of Jesus and Dismas was on the cross to the right of Jesus. In Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend, the name of the impenitent thief is given as Gesmas. The impenitent thief is sometimes referred to as the "bad thief" in contrast to the good thief.

The apocryphal Arabic Infancy Gospel refers to Gestas and Dismas as Dumachus and Titus, respectively. According to tradition – seen, for instance, in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Golden Legend[4] – Dumachus was one of a band of robbers who attacked Saint Joseph and the Holy Family on their flight into Egypt.

New Testament narrative

The earliest version of the story is considered to be that in the Gospel of Mark,[5][3][6] usually dated to around AD 70.[7][8][5] The author says that two bandits were crucified with Jesus, one on each side of him. The passers by and chief priests mock Jesus for claiming to be the Messiah and yet being unable to save himself, and the two crucified with him join in. (Mark 15:27-32)[3] Some texts include a reference to the Book of Isaiah, citing this as a fulfilment of prophecy (Isaiah 53:12: "And he ... was numbered among the transgressors"). The Gospel of Matthew, written around the year 85,[5] repeats the same details.[9] (Matthew 27:38-44)

In the Gospel of Luke version however, from around 80–90,[10][5] the details are varied: one of the bandits rebukes the other for mocking Jesus, and asks Jesus to remember him "when you come into your kingdom". Jesus replies by promising him that he would be with him the same day in Paradise. (Luke 23:33-45)[3] Tradition has given this bandit the name of the penitent thief, and the other the impenitent thief.

The Gospel of John, thought to be written about AD 90–95,[5] also says that Jesus was crucified with two others, but in this account they are not described and they do not speak. (John 19:18-25)

Filipino idiom

Among Filipino Catholics, the name is popularly exclaimed as Hudas, Barabas, Hestas!, a term invoked as an exclamation of disappointment or chastisement, mentioning Gestas along with Judas Iscariot and Barabbas. The phrase gained prominence in the 1973 Filipino television series John En Marsha (1973–1990), starring actor Dolphy along with actresses Nida Blanca and Dely Atay-Atayan. This was popularized by comedienne Chichay.[11]

See also

- List of names for the Biblical nameless

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Penitent thief – Dismas, the other thief crucified alongside Jesus

References

- William Lane Craig; Joe Gorra (1 September 2013). A Reasonable Response: Answers to Tough Questions on God, Christianity, and the Bible. Moody Publishers. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8024-8384-3.

- "William Lane Craig and Bart Ehrman Debate "Is There Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus?"". physics.smu.edu. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Bart D. Ehrman (2008). Whose Word is It?: The Story Behind who Changed the New Testament and why. A&C Black. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-84706-314-4.

- The Golden Legend

- Professor Bart D. Ehrman, The Historical Jesus, Part I, p. 6, The Teaching Company, 2000. Quote: "Scholars are fairly unanimous that they were written some decades after Jesus’ death: Mark, AD 65–70; Matthew and Luke, AD 80–85; and John, AD 90–95."

- Ehrman (2000: 5). Quote: "Maybe we should begin with the earliest Gospel to be written, which most scholars agree was the Gospel of Mark."

- Witherington (2001), p. 31: 'from 66 to 70, and probably closer to the latter'

- Hooker (1991), p. 8: 'the Gospel is usually dated between AD 65 and 75.'

- Harrington (1991), p. 8.

- Davies (2004), p. xii.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0439933/

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "article name needed". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.