Herod Agrippa

Herod Agrippa, also known as Herod or Agrippa I (Hebrew: אגריפס; 11 BC – 44 AD), was a King of Judea from 41 to 44 AD. He was the last ruler with the royal title reigning over Judea and the father of Herod Agrippa II, the last king from the Herodian dynasty. The grandson of Herod the Great and son of Aristobulus IV and Berenice,[1] He is the king named Herod in the Acts of the Apostles 12:1: "Herod (Agrippa)" (Ἡρῴδης Ἀγρίππας).

| Herod Agrippa I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of Judaea | |||||

| |||||

| Reign | 41–44 AD | ||||

| Predecessor | Marullus (Prefect of Judea) | ||||

| Successor | Cuspius Fadus (Procurator of Judea) | ||||

| Born | 11 BC | ||||

| Died | 44 AD (aged 54) Caesarea Maritima | ||||

| Spouse | Cypros | ||||

| Issue | Herod Agrippa II Berenice Mariamne Drusilla | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Herodian Dynasty | ||||

| Father | Aristobulus IV | ||||

| Mother | Berenice | ||||

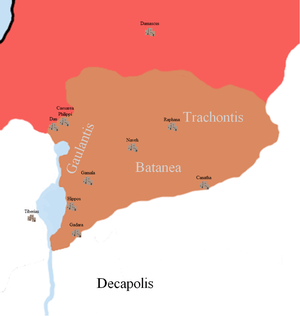

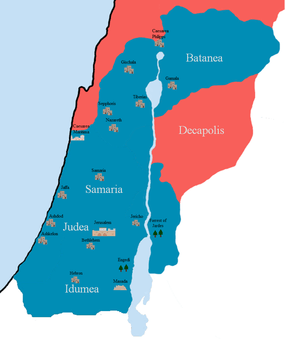

Agrippa's territory comprised most of modern Israel, including Judea, Galilee, Batanaea and Perea. From Galilee his territory extended east to Trachonitis.

Life

Rome

He was born Marcus Julius Agrippa, so named in honour of Roman statesman Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. Josephus informs us that, after the execution of his father, young Agrippa was sent by his grandfather, Herod the Great, to the imperial court in Rome. There, Tiberius conceived a great affection for him, and had him educated alongside his son Drusus, who also befriended him, and future emperor Claudius.[1] On the death of Drusus, Agrippa, who had been recklessly extravagant and was deeply in debt, was obliged to leave Rome, fleeing to the fortress of Malatha in Idumaea. There, it was said, he contemplated suicide.[2]

After a brief seclusion, through the mediation of his wife Cypros and his sister Herodias, Agrippa was given a sum of money by his brother-in-law and uncle, Herodias' husband, Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, and was allowed to take up residence in Tiberias, and received the rank of aedile in that city, with a small yearly income. But having quarrelled with Antipas, he fled to Lucius Pomponius Flaccus, governor of Syria. Soon afterwards he was convicted, through the information of his brother Aristobulus, of having received a bribe from the Damascenes, who wished to purchase his influence with the proconsul, and was again compelled to flee. He was arrested as he was about to sail for Italy, for a sum of money which he owed to the treasury of Caesar, but made his escape, and reached Alexandria, where his wife succeeded in procuring a supply of money from Alexander the Alabarch. He then set sail, and landed at Puteoli. He was favorably received by Tiberius, who entrusted him with the education of his grandson Tiberius Gemellus. He also formed an intimacy with Caligula, then a popular favorite. Agrippa was one day overheard by his freedman Eutyches expressing a wish for Tiberius's death and the advancement of Caligula, and for this he was cast into prison.[1]

Caligula and Claudius

Following Tiberius' death and the ascension of Agrippa's friend Caligula in 37, Agrippa was set free and made king of the territories of Gaulanitis (the Golan Heights), Auranitis, Batanaea, and Trachonitis, which his uncle Philip the Tetrarch had held, with the addition of Abila. Agrippa was also awarded the ornamenta praetoria and could use the title amicus Caesaris ("friend of Caesar"). Caligula also presented him with a gold chain equal in weight to the iron one he had worn in prison, which Agrippa dedicated to the Temple of Jerusalem on his return to his ancestral homeland. In 39, Agrippa returned to Rome, and brought about the banishment of his uncle, Herod Antipas; he was then granted his uncle's tetrarchy, consisting of Galilee and Peraea. This created a Jewish kingdom which did not include Judea at its center.[3][4]

After the assassination of Caligula in 41, Agrippa was involved in the struggle over the accession between Claudius, the Praetorian Guard, and the Senate. How big a part Agrippa played is uncertain; the various sources differ. Cassius Dio simply writes that Agrippa cooperated with Claudius in seeking rule. Flavius Josephus gives us two versions. In The Jewish War, Agrippa is presented as only a messenger to a confident and energetic Claudius. But in The Antiquities of the Jews, Agrippa's role is central and crucial: he convinces Claudius to stand up to the Senate and the Senate to avoid attacking Claudius.[3] After becoming Emperor, Claudius gave Agrippa dominion over Judea and Samaria and granted him the ornamenta consularia, and at his request gave the kingdom of Chalcis in Lebanon to Agrippa's brother Herod of Chalcis. Thus Agrippa became one of the most powerful kings of the east. His domain more or less equaled that which was held by his grandfather Herod the Great.[5]

In the city of Berytus, he built a theatre and amphitheatre, baths, and porticoes. He was equally generous in Sebaste, Heliopolis and Caesarea. Agrippa began the building of the third and outer wall of Jerusalem, but Claudius was not thrilled with the prospect of a strongly fortified Jerusalem, and he prevented him from completing the fortifications.[6] His friendship was courted by many of the neighboring kings and rulers,[1] some of whom he housed in Tiberias, which also caused Claudius some displeasure.[4]

Reign and death

Agrippa returned to Judea and governed it to the satisfaction of the Jews. His zeal, private and public, for Judaism is recorded by Josephus, Philo of Alexandria and the rabbis.[5] Perhaps because of this, his passage through Alexandria in the year 38[7] instigated anti-Jewish riots.[4] At the risk of his own life, or at least of his liberty, he interceded with Caligula on behalf of the Jews, when that emperor was attempting to set up his statue in the Temple at Jerusalem shortly before his death in 41. Agrippa's efforts bore fruit and he persuaded Caligula to temporarily rescind his order, thus preventing the Temple's desecration.[8] However, Philo of Alexandria recounts that Caligula issued a second order to have his statue erected in the Temple[9], which was prevented by Caligula's death.

The Acts of the Apostles, chapter 12 (Acts 12:1–23), where Herod Agrippa is called "King Herod"[10], report that he persecuted the Jerusalem church, having James son of Zebedee killed and imprisoning Peter around the time of a Passover. Blastus is mentioned in Acts as Herod's chamberlain (Acts 12:20).

After Passover in 44, Agrippa went to Caesarea, where he had games performed in honor of Claudius. In the midst of his speech to the public a cry went out that he was a god, and Agrippa did not publicly react. At this time he saw an owl perched over his head. During his imprisonment by Tiberius a similar omen had been interpreted as portending his speedy release and future kingship, with the warning that should he behold the same sight again, he would die.[5] He was immediately smitten with violent pains, scolded his friends for flattering him and accepted his imminent death. He experienced heart pains and a pain in his abdomen, and died after five days.[11] Josephus then relates how Agrippa's brother, Herod of Chalcis, and Helcias sent Aristo to kill Silas.[12]

From Josephus, Antiquities 19.8.2 343-361: "Now when Agrippa had reigned three years over all Judea he came to the city Caesarea, which was formerly called Strato's Tower; and there he exhibited spectacles in honor of Caesar, for whose well-being he'd been informed that a certain festival was being celebrated. At this festival a great number were gathered together of the principal persons of dignity of his province. On the second day of the spectacles he put on a garment made wholly of silver, of a truly wonderful texture, and came into the theater early in the morning. There the silver of his garment, being illuminated by the fresh reflection of the sun's rays, shone out in a wonderful manner, and was so resplendent as to spread awe over those that looked intently upon him. Presently his flatterers cried out, one from one place, and another from another, (though not for his good) that he was a god; and they added, "Be thou merciful to us; for although we have hitherto reverenced thee only as a man, yet shall we henceforth own thee as superior to mortal nature." Upon this the king neither rebuked them nor rejected their impious flattery. But he shortly afterward looked up and saw an owl sitting on a certain rope over his head, and immediately understood that this bird was the messenger of ill tidings, just as it had once been the messenger of good tidings to him; and fell into the deepest sorrow. A severe pain arose in his belly, striking with a most violent intensity. He therefore looked upon his friends, and said, "I, whom you call a god, am commanded presently to depart this life; while Providence thus reproves the lying words you just now said to me; and I, who was by you called immortal, am immediately to be hurried away by death. But I am bound to accept what Providence allots, as it pleases God; for we have by no means lived ill, but in a splendid and happy manner." When he had said this, his pain became violent. Accordingly he was carried into the palace, and the rumor went abroad everywhere that he would certainly die soon. The multitude sat in sackcloth, men, women and children, after the law of their country, and besought God for the king's recovery. All places were also full of mourning and lamentation. Now the king rested in a high chamber, and as he saw them below lying prostrate on the ground he could not keep himself from weeping. And when he had been quite worn out by the pain in his belly for five days, he departed this life, being in the fifty-fourth year of his age and in the seventh year of his reign. He ruled four years under Caius Caesar, three of them were over Philip's tetrarchy only, and on the fourth that of Herod was added to it; and he reigned, besides those, three years under Claudius Caesar, during which time he had Judea added to his lands, as well as Samaria and Cesarea. The revenues that he received out of them were very great, no less than twelve millions of drachmae. But he borrowed great sums from others, for he was so very liberal that his expenses exceeded his incomes, and his generosity was boundless."

Acts 12 gives a similar account of Agrippa's death, adding that "an angel of the Lord struck him down, and he was eaten by worms":

20 Now Herod was angry with the people of Tyre and Sidon. So they came to him in a body; and after winning over Blastus, the king’s chamberlain, they asked for a reconciliation, because their country depended on the king’s country for food. 21 On an appointed day Herod put on his royal robes, took his seat on the platform, and delivered a public address to them. 22 The people kept shouting, “The voice of a god, and not of a mortal!” 23 And immediately, because he had not given the glory to God, an angel of the Lord struck him down, and he was eaten by worms and died.

— Acts 12:20-23

The Jewish Encyclopedia speculated that Agrippa's "sudden death at the games in Cæsarea, 44, must be considered as a stroke of Roman politics."[13]

.jpg)

Josephus gave Agrippa a positive legacy and related that he was known in his time as "Agrippa the Great".[14] The Talmud also has a positive view of his reign: The Mishnah explained how the Jews of the Second Temple era interpreted the requirement of Deuteronomy 31:10–13 that the king read the Torah to the people. At the conclusion of the first day of Sukkot immediately after the conclusion of the seventh year in the cycle, they erected a wooden dais in the Temple court, upon which the king sat. The synagogue attendant took a Torah scroll and handed it to the synagogue president, who handed it to the High Priest's deputy, who handed it to the High Priest, who handed it to the king. The king stood and received it, and then read sitting. King Agrippa stood and received it and read standing, and the sages praised him for doing so. When Agrippa reached the commandment of Deuteronomy 17:15 that “you may not put a foreigner over you” as king, his eyes ran with tears, but they said to him, “Don’t fear, Agrippa, you are our brother, you are our brother!”[15] The king would read from Deuteronomy 1:1 up through the shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), and then Deuteronomy 11:13–21, the portion regarding tithes (Deuteronomy 14:22–29), the portion of the king (Deuteronomy 17:14–20), and the blessings and curses (Deuteronomy 27–28). The king would recite the same blessings as the High Priest, except that the king would substitute a blessing for the festivals instead of one for the forgiveness of sin. (Mishnah Sotah 7:8; Babylonian Talmud Sotah 41a.) In a 2013 conference, Professor Gabriel Barkay suggested that the so called Tomb of Absalom (of the 1st century C.E.) is in fact that it could be the tomb of Herod Agrippa, the grandson of Herod the Great, based in part on the similarity to Herod's newly discovered tomb at Herodium.

Progeny

By his wife Cypros he had two sons and three daughters. They were:

- Herod Agrippa II [b. 27/28 AD?-d. 93 AD?] became the eighth and final ruler from the Herodian family, but without any control of Judea. He supported Roman Rule and died childless.

- Berenice [b. 28-after 81 AD], who first married Marcus Julius Alexander, son of Alexander the Alabarch around 41 AD. After Marcus Julius died [44 AD], she married her uncle Herod, king of Chalcis by whom she had two sons, Berenicianus and Hyrcanus.[16]. She later lived with her brother Agrippa II, reputedly in an incestuous relationship. Finally, she married Polamo, king of Cilicia as alluded to by Juvenal.[17] Berenice also had a common law relationship with the Roman emperor Titus.[18]Similar to her brother Herod Agrippa II, she supported Roman Rule.

- Drusus [b.?-d.?]According to Josephus, there was also a younger brother called Drusus, who died before his teens.[19]

- Mariamne [b. 34/35-], who married Julius Archelaus, son of Chelcias 49/50 AD; they had a daughter Berenice (daughter of Mariamne) [b. 50 AD] who lived with her mother in Alexandria, Egypt after her parents' divorce. Around 65 AD Mariamne left her husband and married Demetrius of Alexandria who was its Alabarch and had a son from him named Agrippinus.[20]

- Drusilla [38–79 AD], who married first to Gaius Julius Azizus, King of Emesa and then to Antonius Felix, the procurator of Judaea.[21][22][23][24] Drusilla and her son Marcus Antonius Agrippa died in Pompeii during the eruption of Vesuvius. A daughter, Antonia Clementiana, became a grandmother to a Lucius Anneius Domitius Proculus. Two possible descendants from this marriage are Marcus Antonius Fronto Salvianus (a quaestor) and his son Marcus Antonius Felix Magnus, a high priest in 225.

Family tree

Agrippa in other media

- Herod Agrippa is the protagonist of the Italian opera, L’Agrippa tetrarca di Gerusalemme (1724) by Giuseppe Maria Buini (mus.) and Claudio Nicola Stampa (libr.), first performed at the Teatro Ducale of Milan, Italy, on August 28, 1724.[25]

- Herod Agrippa is a major figure in Robert Graves' novel Claudius the God, as well as the BBC television adaptation I, Claudius, wherein he was portrayed by James Faulkner as an adult and Michael Clements as a child. He is depicted as one of Claudius's closest lifelong friends. Herod acts as Claudius's last and most trustworthy friend and advisor, giving him the key advice to trust no one, not even him. This advice proves prophetic at the end of Herod's life, where he is depicted as coming to believe that he is a prophesied Messiah and raising a rebellion against Rome, to Claudius's dismay. However, he is struck down by a possibly supernatural illness and sends a final letter to Claudius asking for forgiveness.

See also

- Herodian dynasty

- Herodian kingdom

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- List of Hasmonean and Herodian rulers

Notes

- Mason, Charles Peter (1867), "Agrippa, Herodes I", in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 77–78

- Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae xviii. 7. § 2

- Schwartz, Daniel R. Agrippa I Mohr 1990

- Rajak, Tessa (1996), "Iulius Agrippa (1) I, Marcus", in Hornblower, Simon (ed.), Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press

-

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) v.iv.§ 2

- AgrippaI, Daniel R. schwartz, 1990

- Ebner, Eliezer, History of the Jewish People, The Second Temple Era, Mesorah Publications Ltd. 1982, p. 155

- Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XLIII.346.

- The identification is based on the fact that Agrippa was the only Herod who had authority in Jerusalem at that time. (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 19.5.1) and the similar death accounts. The New Testament also mention Agrippa's uncle and predecessor Herod Antipas as authorizing the execution of John the Baptist and playing a role in the trial of Jesus (Matthew 14:3–12, Mark 6:17–29, Luke 23:5–12) as well as Agrippa's son, Herod Agrippa II as assisting in the trial of the Apostle Paul (Acts 25:13 – 26:32).

- Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae xix. 345–350 (Chapter 8 para 2)

- Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae xix. Chapter 8 para 3 But before the multitude were made acquainted with Agrippa's being expired, Herod the king of Chalcis, and Helcias the master of his horse, and the king's friend, sent Aristo, one of the king's most faithful servants, and slew Silas, who had been their enemy, as if it had been done by the king's own command.

- Markus Brann, "AGRIPPA I. (M. JULIUS AGRIPPA, also known as Herod Agrippa I.)"; Jewish Encyclopedia, ed. Isidore Singer; Funk & Wagnalls, 1906.

- Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae xvii. 2. § 2

- Ebner, 1982, p.156

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XX.5.2

- Juvenal, Satires vi. 156

- Suetonius, Titus 7

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.5.4

- Ciecieląg Jerzy, Polityczne dziedzictwo Heroda Wielkiego. Palestyna w epoce rzymsko-herodiańskiej, Kraków 2002, s. 75-77, 140.

- Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae xvii. 1. § 2, xviii. 5–8, xix. 4–8

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews i. 28. § 1, ii. 9. 11

- Cassius Dio lx. 8

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History ii. 10

- G. Boccaccini, Portraits of Middle Judaism in Scholarship and Arts (Turin: Zamorani, 1992).

References

- Yohanan Aharoni & Michael Avi-Yonah, "The MacMillan Bible Atlas", Revised Edition, p. 156 (1968 & 1977, by Carta Ltd.).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Agrippa I. |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Agrippa I.

- Agrippa I, article in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Sergey E. Rysev. Herod and Agrippa

Herod Agrippa House of Herod Born: 11 BC Died: 44 AD | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Tetrarch Herod Philip II |

King of Batanaea 37 AD – 41 AD |

Vacant Title next held by King Agrippa II |

| Vacant Title last held by Tetrarch Herod Antipas |

King of Galilee 40 AD – 41 AD |

Title extinct |

| Vacant governed by Prefect Title last held by King Herod the Great |

King of Judaea 41 AD – 44 AD |

Title extinct |