Ijamsville, Maryland

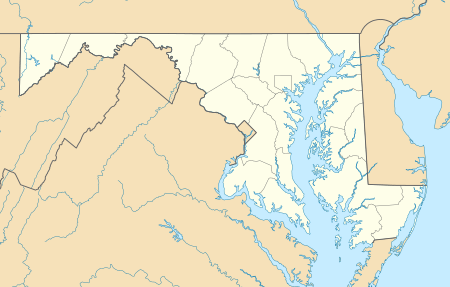

Ijamsville ( /ˈaɪəmzvɪl/ EYE-əmz-vil) is an unincorporated community located 7 miles (11 km) southeast of Frederick,[1] in Frederick County, Maryland, United States.[2] The town was founded by Plummer Ijams, a descendant of Welsh immigrants, from whom the town took its name. The discovery of high-quality slate in the area led to Ijamsville's brief era as a mining town, which lasted until its transition to agriculture in the mid-1800s. In the mid-to-late 20th century, large quantities of land in Ijamsville were purchased by developers, and the town became primarily residential as a suburb of Frederick, Baltimore, and D.C..

Ijamsville, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| |

Ijamsville Location in Maryland  Ijamsville Ijamsville (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 39°21′38″N 77°19′22″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Elevation | 107 m (351 ft) |

| ZIP code | 21754 |

History

Founding and name

In 1785, a Maryland native named Plummer Ijams moved to Frederick County, having purchased a tract of land called the "Paradise Grant" from the government. His family was originally from Wales and emigrated to the Anne Arundel region sometime during the 17th century.[3] The land was approximately 8 miles (13 km) southeast of the city of Frederick and cost Plummer one pound, fifteen shillings, and four pence per acre.[4][5] Plummer established a plantation on his new land, growing primarily wheat and barley, with a small number of slaves.[3] Plummer had at least two children: a son named Plummer II and a younger child named John (born in 1789). Plummer Jr. built a gristmill along nearby Bush Creek (which stood until demolished in 1994) while John enlisted in the War of 1812 and rose to the rank of captain.[3][6] Plummer Ijams Sr. died on June 14, 1796, but his children and their family remained in the area well into the 19th century.

In the 1780s and '90s, other settlers (including the Musetter, Montgomery, and Riggs families) established themselves nearby, purchasing land either from the government or directly from the Ijams family. One of the most important were the three brothers John, William, and Thomas Duvall, whose 130-acre (53 ha) tract of land became known as "Duvall's Forest." The Duvalls discovered large deposits of slate in 1800, and two quarries were operational by 1812, at least one owned by a man named Gideon Bantz.[5][7] Veins of this unique blue-green or purple volcanic "Ijamsville phylite" "lie west and southwest of Westminster and extend southwest from Frederick County into Montgomery County" and are largely responsible for the community's early growth.[3][8][9]

Around 1831, the early B&O Railroad asked the Ijams family for permission to construct railroad tracks through its land. Plummer II accepted on the condition that a depot also be built, in part to ease the transport of slate into the local cities. The B&O christened the heretofore unnamed community "Ijams' Mill and Bantzs' Slate Quarries." On March 13, 1832, four horse-drawn railroad cars traveled through the town on their inaugural journey from Baltimore to Frederick.[3]

In 1786, the Ijams family requested that a post office be constructed on their land.[4] This marks the first instance where the region was considered a community, before the arrival of the B&O. The office was finally constructed in 1832, and Plummer II served as its first postmaster. On June 22, 1832, the U.S. Postal Service shortened the town's name to "Ijamsville."

Expansion

Over the next few decades, the town expanded steadily into a "typically colorful mining town".[3] An influx of Welsh immigrants who came to work the slate mines (now equipped with steam-powered processing equipment) led to the establishment of a residential section north of the railroad tracks. Most of the homes in this section had slate roofing from the Duvall slate quarry and wooden walls from Duvall's Forest.[10] In fact, Ijamsville slate was used as roofing material throughout Frederick and even in Washington, D.C..[11] Many small shops grew up towards the center of the town, catering to the needs of residents. The most notable of these, A. K. Williams's General Store, housed the post office and B&O ticketing office.[3] The building itself stood for over one hundred years before being finally demolished in 2015. In May 1887, Ijamsville's Women's Home Missionary Society established a "Young People's Circle" which drew teenagers and young adults from the countryside into town. By that time, the town could boast a coppershop, carpenter's shop, wheelwright, stable, boardinghouse, shoemaker, milliner, and the gristmill and a sawmill constructed by the original Ijams residents (sold in 1874 to the McComas family for around $6,900).[6][12]

Resident Chris M. Riggs began a fundraising campaign in 1854 to construct a church in Ijamsville. Local Episcopalians donated a land lot to the cause, farmer Charles Hendry fired the bricks, and the women of the town made and sold quilts to raise the needed funds. The roof was made of Ijamsville phyllite.[13] On July 25, 1858, Ijamsville's Methodist Episcopal Church was officially dedicated and received its first two ministers—Reverends Thomas B. Sergeant and T. M. Reese—who happened to be Lutheran.[12] The church building was rebuilt in 1890 after a fire, but is one of the few original town buildings still standing today.[14] The church's basement served as the local school until 1876, when a building adjacent to the church was constructed to house the few students.[15] Professor Chasuble McGill Luckett was the school's first teacher, with other teachers (including some women form the Riggs family) riding in on horseback to help when needed. The school reportedly took $509.98 to operate each year.[3]

Local farms continued to produce wheat, barley, corn, tobacco, and sheep. The town's flour and slate were well recognized in Baltimore and Frederick, two of the most important stops on the local railroad.[12] Ijamsville nearly even developed a small pottery industry when potter Artemus Wolf came from Vermont to the town in 1863. He discovered that the soil near the Ijams's spring had the perfect clay content for firing and glazing. With local merchant Benjamin Franklin Sellman, he began selling "Wolf and Sellman" pottery that sold very well to the nearby towns and farms. Unfortunately for the town, when Wolf journeyed to Vermont in 1876, hoping to form a full-fledged company and return, he caught pneumonia and died. Sellman's store closed down shortly afterward, and no other potters ever came to Ijamsville.[3][16]

Transition to agriculture

With the onset of the Civil War, the demand for slate dropped off sharply, as did the available workforce. To compound the problem, the B&O railroad ran an injunction against the local quarry owners for undermining their tracks. These two factors led to the closing many of the town's quarries in 1870. An outside mining company, the Maine Co., attempted to start a mine in Ijamsville but gave up by 1874.[4] Christopher Riggs, a carpenter, then owned and operated the only remaining slate mine, which produced only powdered slate (used as a fertilizer base, a purple dye for paint, or in vitrified bricks).[3] The town shrunk considerably with the end of its mining industry; the 1880 census listed only 71 residents.[12][17]

With the end of mining, Ijamsville transitioned into an agricultural town. At the time, land cost $35–50 an acre. Farmers could produce 15-30 bushels of wheat, 30-50 barrels of corn, ½ ton tobacco, and/or two tons of hay an acre, per season. The local farms changed hands several times, but remained mostly unchanged through the 1940s. The church was run in the late 1800s by a Baptist, progressive leader, and former forty-niner named Isaac T. McComas. Other important residents of the period included a Mrs. Eliza Ijams, who was inspired by her two deaf children (Mary and Plummer III) to become involved with the Maryland School for the Deaf located in nearby Frederick City.[3] Plummer Ijams's granddaughter, Mollie Ijams, was a member of the school's first graduating class.[18] Another local school, the Glenellen Academy, was established in 1874 by Professor Herbert Thompson and his wife Ellen.[11] The school's annual tuition was $100, and specialized in science of all levels. Enrollment peaked at about 40 students, and the school continued to offer lessons even after its official "closure" in 1888. An interesting local legend held that Mrs. Thompson was the ghostwriter of the romance novel Lorna Doone while she lived in England. Though Lady Ellen and some of the couple's students often claimed that she was the book's true author and requested that her relative, R. D. Blackmore, publish it under his name, no definitive proof was ever given for their story.[19]

The Westport Paving Brick Company of Baltimore reopened one of the slate quarries from 1913-1937; company records from 1922 show 120 tons of slate and shale being shipped daily. After about 1925, the easy availability of automobiles led to the death of the railroad. The Ijamsville depot was bypassed, though the actual railroad tracks were still open to non-local traffic. As a result, when the Westport Company's operation closed down in 1937, there were no longer any advantages to mining in a small town like Ijamsville, and no quarry has existed in the town since.[3][20]

Business at the turn of the century

At the turn of the century, only the town's flour mill and creamery were doing well. By 1925, only an antique shop and bakery remained. One of the town's only crimes—the midnight robbery of the Turner family mill by three "highwaymen"—occurred during that summer, but Ijamsville otherwise remained a "quiet country village".[20] The center of the town's social life remained the Methodist church and its Homemakers' Club. The church converted the old public school building into a social hall upon its closure in 1932. From that time on, Ijamsville residents were serviced by local Frederick County schools (in particular those of nearby Urbana, Maryland). A large patch of grass sandwiched between a hill and the railroad tracks known as Moxley Field housed Ijamsville champion baseball team. Over the years, the team became "almost like a farm team for the Orioles" and was one of the town's main attractions, now that the mining industry had been supplanted by agriculture.[13][21]

One business established during late 1800s became Ijamsville's other attraction. The physical building was constructed by Christopher Riggs in 1862 for use by Welsh mining families. Riggs's son, Dr. George Henry Riggs (a local family physician and psychiatrist), converted the structure into a "sanatorium for nervous and mental health disorders" in 1896.[11] It was in operation until 1969 and treated over a thousand patients from as far away as North Carolina and Pennsylvania.[22] The hospital was called "Riggs' Cottage" or, more formally, "Riggs Cottage Sanitariym for Nervous and Mental Diseases".[22][23] The hospital changed owners at least once during its lifetime, as records show its purchase in 1939 by a Dr. and Mrs. McAdoo.[22] The hospital was originally open to both men and women, but the lack of male nurses during World War I forced the owners to limit it to only female patients. More difficult patients were transferred to a state hospital. An advertisement from the era claimed "each patient received individual psychotherapeutic attention, occupation, and recreation... under the most favorable hygienic conditions".[22]

Development and suburbanization

Ijamsville remained a quiet agricultural town throughout most of the 20th century. Its few remaining businesses gradually closed down or changed hands: the hospital was converted into an upscale French restaurant (Gabriel's French Provincial Inn), the baseball field was purchased by the Frederick Pony Club, and many of the older structures in town were torn down and not rebuilt.[11][24] The post office was closed down in 1983 (postal services were then provided out of Monrovia, MD).[18]

Without a post office, railroad depot, or other businesses in town, there was nothing to attract new farmers to the area. As the older farmowners died and their children moved closer to city centers, more and more land was put up for sale. By 1989, developers were making purchases of as much as $1 million's worth of land at a time. After the construction of wells and septic fields, the area developed rapidly. Houses were built and filled with families looking for work in nearby Frederick, Baltimore, or Washington, D.C.[25]

By 2000, Ijamsville was divided into three areas: the original town center by the railroad tracks, with a few historic homes left intact; several large family farms raising mostly cows, corn, and soybeans; and large sections of suburban-style homes.[11][26] New companies came into the area to tap the growing upper middle class market in Ijamsville and nearby Urbana. The businesses they established included golf courses and a petting zoo.[27][28]

Two religious centers were established as well: a Roman Catholic, Jesuit Saint Ignatius of Loyola parish (originally from Buckeystown, MD and with another church building in Urbana); and the Hindu Sri Bhaktha Anjaneya Temple, the "only [Hindu] temple in the United States dedicated to [Bhaktha]-Anjaneya."[29][30][31] The temple was completed in late 2014-early 2015, while the church has stood since the 1980s and undergone several expansions to accommodate new parishioners.[30][32]

A Quaker school named Friends Meeting School (FMS) moved to the area in 1997, sharing space with Pleasant Grove United Methodist Church, also located in Ijamsville.[33][34] FMS was originally established for preschool through 6th grade, but expanded until it reached its current size in 2013, serving pre-K through 12th grade.[35] As the school expanded, it purchased and moved onto land near Windsor Knolls Middle school.[35] The Christian Life Center, a United Pentecostal organization from Rockville, MD, purchased land near FMS in early 2012 and began holding services in Damascus High School. The organization moved into their newly constructed building in August 2013.[36]

Education

Frederick County Public Schools operates area schools. Schools with Ijamsville postal addresses include Oakdale Elementary School, Oakdale Middle School, Urbana Middle School, Windsor Knolls Middle School, Oakdale High School, and Urbana High School.[37]

Notable people

- Shawn Hatosy, Actor

Gallery

Ijamsville at night

Ijamsville at night Ijamsville, seen from the B&O Railroad old line

Ijamsville, seen from the B&O Railroad old line- Old millstone at the corner of Green Valley Rd. and Prices Distillery Rd.

- Cow pasture at the corner of Ijamsville Rd. and Mussetter Rd.

Home on Mussetter Rd., with Ijamsville slate roofing on its turret

Home on Mussetter Rd., with Ijamsville slate roofing on its turret- A closeup view of Ijamsville's United Methodist Church

- The Ijamsville church social hall and former schoolhouse

Original barn/outbuilding behind church social hall

Original barn/outbuilding behind church social hall Locally fired bricks in the 2015 A. K. Williams Store rubble

Locally fired bricks in the 2015 A. K. Williams Store rubble

References

- "Google Maps".

- "Geographic Names Information System". Ijamsville (Populated Place). U.S. Geological Survey. 2009-01-29.

- Moylan, Charles E. (1951). Ijamsville: The Story of a Country Village. Baltimore, MD.

- Spaur, Michael L. (January 24, 1979). "What's in the Name?: Ijamsville". The Frederick News Post. Frederick, MD. pp. C-4.

- Cline, Dan (August 26, 1978). "Ijamsville -- Famous Quarry, Railroad Town". Cities and Towns.

- McComas, Isaac Taylor (2004). Isaac Taylor McComas Diary, 1883. Philadelphia, PA: Charles McComas Robb. pp. 2, 4, 50, 56.

- Roach, Eugene W. (1960). A Historic Peek at New Market and Ijamsville. Mount Airy, MD. p. 14.

- Scweitzer, Peter. "Ijamsville Formation and Marburg Schist". U.S. Geological Survey. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Keroher, Grace C. (1966). Lexicon of Geologic Names of the United States for 1936-1960, Part 2. California: U.S. Government Print Office. p. 1856.

- "Inventory F-5-12: Ijamsville Survey District" (PDF). Inventory Form for State Historic Sites Survey. Maryland Historical Trust. 1977. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Beck, Karen (March 14, 2002). "Ijamsville Then and Now: From Busy Town to Sleepy Suburb". Gazette.net. Maryland Community News Online. Retrieved March 17, 2002.

- Scharf, Thomas J. (1968). History of Western Maryland: Volume 1. Baltimore: Baltimore Regional Publishing Company. pp. 598, 611.

- Erickson, Marie Anne (2012). Price, Ingrid (ed.). Frederick County Chronicles: The Crossroads of Maryland. Charleston: The History Press. pp. 124–127. ISBN 9781609497750.

- "Inventory F-5-10: Ijamsville Methodist Church" (PDF). Inventory Form for State Historic Sites Survey. Maryland Historical Trust. August 9, 1977. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Inventory F-5-11: Ijamsville School House" (PDF). Inventory Form for State Historic Sites Survey. Maryland Historical Trust. November 25, 1977. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "The News from Frederick, Maryland". The News. Frederick, MD. March 3, 1951. p. 8. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "1880 Census Records Search". CensusRecords.com. brightsolid. p. 1. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Seng, Joe (May 23, 1990). "Time Has Bypassed Ijamsville Community". Mount Airy Courier -- Gazette. Mount Airy, MD.

- "Glen Ellen Farm: Then and Now". glenellenfarm.com. Glen Ellen Farm. 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Hill, Clare K. (June 6, 2011). "Ijamsville: The History of a Village". Town Courier Online. The Urbana Town Courier. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Erickson, Marie Anne (June 1990). "Ijamsville". FREDERICK Magazine. Frederick, MD. p. 11.

- Bohn, Suzanne (May 1977). "Inventory F-5-9: Rigg's Sanatorium" (PDF). Inventory Form for State Historic Sites Survey. Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- Stedman, Thomas Lathrop, ed. (1916). Medical Record: A Weekly Journal of Medicine and Surgery (Vol 90). Michigan: William Wood and Company. p. 33.

- "Gabriel's Inn: History". gabrielsinn.wordpress.com. Gabriel's Inn. February 14, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Boin, Sonja (August 25, 1989). "Ijams Country May One Day be Covered with New Homes". The News: Frederick MD. Frederick, MD.

- Rigaux, Pamela (October 3, 2007). "Six Houses in Ijamsville Will Still Go Up". Frederick News Post. Frederick, MD. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Carignan, Sylvia (April 1, 2016). "Hello Frederick: Urbana, Ijamsville, Green Valley". Frederick News Post: Lifestyle. Frederick, MD. The Frederick News Post. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Brown, Jeremy. "History of Green Meadows Farm". greenmeadowsevents.com. Green Meadowns Farm. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Hernandez, Nancy (November 23, 2013). "Visiting Sri Bhaktha Anjaneya Temple".

- "St. Ignatius of Loyola Parish". e-stignatius.org. Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- "Sri Bhaktha Anjaneya Temple". SBAT. iStudio Technologies. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Alt, Sally (August 29, 2014). "Construction for Temple in Ijamsville Underway". Community News. The Urbana Town Courier. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- "Pleasant Grove United Methodist Church". The People of the United Methodist Church. United Methodist Communications. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "Quaker values moved educator to open two schools". WTOP Online. WTOP. February 24, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "About Friends Meeting School". FriendsMeetingSchool.org. FMS. 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "Over 3 Decades of CLC History". CLCEast.org. August 8, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "Schools Directory." Frederick County Public Schools. Retrieved on August 12, 2017.