Giant forest hog

The giant forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni), the only member of its genus, is native to wooded habitats in Africa and is generally considered the largest wild member of the pig family, Suidae; however, a few subspecies of the wild boar can reach an even larger size.[2] Despite its large size and relatively wide distribution, it was first described only in 1904. The specific name honours Richard Meinertzhagen, who shot the type specimen in Kenya and had it shipped to the Natural History Museum in England.[3]

| Giant forest hog | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Suidae |

| Genus: | Hylochoerus Thomas, 1904 |

| Species: | H. meinertzhageni |

| Binomial name | |

| Hylochoerus meinertzhageni Thomas, 1904 | |

| |

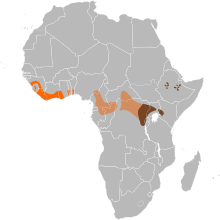

H. m. ivoriensis H. m. rimator H. m. meinertzhageni | |

Description

The giant forest hog is, on average, the largest living species of suid. Adults can measure from 1.3 to 2.1 m (4 ft 3 in to 6 ft 11 in) in head-and-body length, with an additional tail length of 25 to 45 cm (9.8 to 17.7 in). Adults stand 0.75 to 1.1 m (2 ft 6 in to 3 ft 7 in) in height at the shoulder, and can weigh from 100 to 275 kg (220 to 606 lb).[4][5][6][7][8] Females are smaller than males. Females weigh a median of approximately 167 kg (368 lb), as opposed to males, which weigh a median of 210 kg (460 lb).[9] The eastern nominate subspecies is slightly larger than H. m. rimator of Central Africa and noticeably larger than H. m. ivoriensis of West Africa,[4] with the latter sometimes being scarcely larger than related species such as the bushpig with a top recorded weight of around 150 kg (330 lb).[8] The giant forest hog has extensive hairs on its body, though these tend to become less pronounced as the animal ages. It is mostly black in colour on the surface, though hairs nearest the skin of the animal are a deep orange colour. Its ears are large and pointy, and the tusks are proportionally smaller than those of the warthogs, but bigger than those of the bushpig. Nevertheless, the tusks of a male may reach a length of 35.9 centimetres (14.1 in).[8]

Distribution

Giant forest hogs occur in west and central Africa, where they are largely restricted to the Guinean and Congolese forests. They also occur more locally in humid highlands of the Rwenzori Mountains and as far east as Mount Kenya and the Ethiopian Highlands. They are mainly found in forest-grassland mosaics, but can also be seen in wooded savanna and subalpine habitats at altitudes up to 3,800 m (12,500 ft).[5] They are unable to cope with low humidity or prolonged exposure to the sun, resulting in them being absent from arid regions and habitats devoid of dense cover.[5]

Habits

The giant forest hog is mainly a herbivore, but also scavenges.[10] It is usually considered nocturnal, but in cold periods, it is more commonly seen during daylight hours, and it may be diurnal in regions where protected from humans.[4] They live in herds (sounders) of up to 20 animals consisting of females and their offspring, but usually also including a single old male.[4] Females leave the sounder before giving birth and return with the piglets about a week after parturition. All members of the sounder protect the piglets, and a piglet can nurse from all females.[8] Boars fight by running head on into each other, followed by head pushing and attempts to slash the opponent with their lower tusks. [11]

As all suids of Sub-Saharan Africa, the giant forest hog has not been domesticated, but it is easily tamed and has been considered to have potential for domestication.[4] In the wild, though, the giant forest hog is more feared than the red river hog and the bushpig (the two members of the genus Potamochoerus), as males sometimes attack without warning, possibly to protect their group.[4] It has also been known to drive spotted hyenas away from carcasses and fights among males resulting in the death of one of the participants are not that uncommon.[8] Despite its size and potential for aggressive behaviour, they have been known to fall prey to leopards (probably almost exclusively large male forest leopards which are often larger than their savannah-dwelling equivalents) and clans of spotted hyenas. Although in some localities the lion may also be a predator of giant forest hogs, the species are usually segregated by habitat, as African lions do not generally occur in the densely forested habitats inhabited by this suid.[12][13]

References

- d'Huart, J.P. & Klingel, H. (2008). "Hylochoerus meinertzhageni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- Meijaard, E., J.P. d'Huart, and W.L.R. Oliver (2011). Suidae (Pigs), pp. 248–291 in: Wilson, D.E., and R.A. Mittermeier, eds (2011). Handbook of the Mammals of the World, vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4

- Garfield, B. (2007). The Meinertzhagen Mystery: The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud. Potomac Books, Washington. Pp. 60. ISBN 1-59797-041-7

- Novak, R. M. (editor) (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. pp. 1059–1060. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- Kingdon, J. (1997). The Kingdon Guide to African Mammals. Academic Press Limited, London. pp. 332–333. ISBN 0-12-408355-2

- West, G., Heard, D., & Caulkett, N. (Eds.). (2008). Zoo animal and wildlife immobilization and anesthesia. John Wiley & Sons.

- Estes, R. (1991). The behavior guide to African mammals (Vol. 64). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Huffman, B. (2004). Giant forest hog. Ultimate Ungulates.

- Estes, R. D. (1999). The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, and Primates. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Dzanga Forest Elephants (2008). Departures and Arrivals.

- Geist, Valerius (1966). "The Evolution of Horn-Like Organs". Brill. 27 (1–2): 175–214. doi:10.1163/156853966X00155.

- Hart, J. A.; Katembo, M.; Punga, K. (1996). "Diet, prey selection and ecological relations of leopard and golden cat in the Ituri Forest, Zaire". African Journal of Ecology. 34 (4): 364–379. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1996.tb00632.x.

- Hayward, M. W. (2006). "Prey preferences of the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) and degree of dietary overlap with the lion (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology. 270 (4): 606–614. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00183.x.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hylochoerus meinertzhageni. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Hylochoerus |