Hyaenodontidae

Hyaenodontidae ("hyena teeth") is a family of extinct predatory mammals, and is the type family of the extinct mammalian order Hyaenodonta. Hyaenodontids were important mammalian predators that arose during the late Paleocene and persisted well into the Miocene.[1] They were considerably more widespread and successful than the oxyaenids, the other clade historically considered part of Creodonta.[2]

| Hyaenodontidae | |

|---|---|

| |

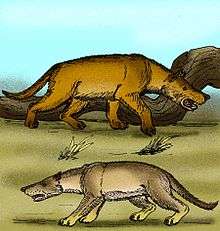

| Hyaenodon gigas and H. mongoliensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Creodonta |

| Clade: | †Hyaenodonta |

| Family: | †Hyaenodontidae Leidy, 1869 |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

General characteristics

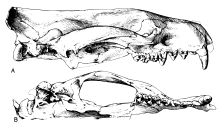

Hyaenodontids are characterized by long skulls, slender jaws, slim bodies, and a plantigrade stance. They generally ranged in size from 30 to 140 cm at the shoulder.[2] While Hyaenodon gigas, the largest Hyaenodon species, was as much as 1.4 m high at the shoulder, 10 feet long and weighed about 500 kg, most were in the 5–15 kg range, equivalent to a mid-sized dog.[3] The anatomy of their skulls show that they had a particularly acute sense of smell, while their teeth were adapted for shearing, rather than crushing.[2]

Because of their size range, it is probable that different species hunted in different ways, which allowed them to fill many different predatory niches. Smaller ones would hunt in packs during the night like wolves, and bigger, fiercer ones would hunt alone during the daylight, using their sheer size and their mighty jaws as their principal weapon. The carnassials in a hyaenodontid are generally the second upper and third lower molars. However, some hyaenodontids possessed as many as three sequential pairs of carnassials or carnassial-like molar teeth in their jaws.[4] Hyaenodontids, like all creodonts, lacked post-carnassial crushing molar teeth, such as those found in many carnivoran families, especially the Canidae and Ursidae, and thus lacked dental versatility for processing any foods other than meat.[5]

Hyaenodontids are very unusual in regards to their tooth replacement. Studies on Hyaenodon show that juveniles took 3–4 years in the last stage of tooth eruption, implying a very long adolescent phase. In North American forms, the first upper premolar erupts before the first upper molar, while European forms show an earlier eruption of the first upper molar.[6]

At least one hyaenodontid lineage, Apterodontinae, was specialised for aquatic, otter-like habits.[7]

Range

Having evolved in Africa during the Paleocene,[7][8] hyaenodontids soon after spread into India and Europe, implying close biogeographical connections between these areas.[9] Afterwards they dispersed into Asia from either Europe or India, and finally North America.[10][11]

They were important hypercarnivores in Eurasia, Africa and North America during the Oligocene, but gradually declined, with almost the entire family becoming extinct by the close of the Oligocene. Only four genera, Megistotherium, its sister genera Hyainailouros and Dissopsalis, and the youngest species of Hyaenodon, H. weilini, survived into the Miocene, of which, only Dissopsalis survived long enough to go extinct at the close of the Miocene.[1] Traditionally this has been attributed to competition with carnivorans, but no formal examination of the correlation between the decline of hyaenodontids and the expansion of carnivorans has been reccorded, and the latter may simply have moved into vacant niches after the extinction of hyaenodontid species.

Relations

Hyaenodontids were historically classified in Creodonta, alongside other predatory mammal groups like oxyaenids. Some researchers consider the clade a wastebasket taxon containing two unrelated clades assumed to be closely related to or ancestral to Carnivora.[6][7][12][13][14][15] However, a recent phylogenetic analysis of Paleogene mammals supports the monophyly of Creodonta, and places them in Ferae, close to Pholidota.[16]

Genera

- ORDER CREODONTA creodonts

- Family Hyaenodontidae[17]

- Genus Ischnognathus (incertae sedis)

- Genus Tinerhodon (incertae sedis)

- Genus Cartierodon

- Subfamily Arfiinae

- Genus Arfia

- Subfamily Hyaenodontinae

- Genus Hyaenodon

- Genus Neoparapterodon

- Genus Propterodon

- Subfamily Indohyaenodontinae

- Genus Indohyaenodon

- Genus Kyawdawia

- Genus Paratritemnodon

- Genus Yarshea

- Subfamily Limnocyoninae

- Genus Iridodon

- Genus Limnocyon (syn. Telmatocyon)

- Genus Oxyaenodon

- Genus Prolaena

- Genus Prolimnocyon

- Genus Thereutherium

- Genus Thinocyon

- Subfamily Proviverrinae

- Genus Alienetherium

- Genus Allopterodon

- Genus Consobrinus

- Genus Cynohyaenodon

- Genus Eurotherium

- Genus Leonhardtina

- Genus Lesmesodon

- Genus Matthodon

- Genus Minimovellentodon

- Genus Morlodon

- Genus Orienspterodon

- Genus Oxyaenoides

- Genus Paenoxyaenoides

- Genus Paracynohyaenodon

- Genus Paravagula

- Genus Praecodens

- Genus Preonictis

- Genus Preregidens

- Genus Prodissopsalis

- Genus Proviverra

- Genus Quercitherium

- Subfamily Sinopinae[18]

- Genus Acarictis

- Genus Galecyon

- Genus Gazinocyon

- Genus Prototomus

- Genus Proviverroides

- Genus Pyrocyon

- Genus Sinopa (syn. Stypolophus, Triacodon)

- Genus Tritemnodon

- Family Hyaenodontidae[17]

The Machaeroidinae are sometimes placed here, e.g. by Egi, 2001.[3] Hyainailourinae was elevated to family rank in 2015.[19]

References

- Barry, J. C. (1988). "Dissopsalis, a middle and late Miocene proviverrine creodont (Mammalia) from Pakistan and Kenya". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 48 (1): 25–45.

- Lambert, David and the Diagram Group (1985): The Field Guide to Prehistoric Life. Facts on File Publications, New York. ISBN 0-8160-1125-7

- Egi, Naoko (2001). "Body Mass Estimates in Extinct Mammals from Limb Bone Dimensions: the Case of North American Hyaenodontids". Palaeontology. 44 (3): 497–528. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00189.

- Wang, Xiaoming; and Tedford, Richard H. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. p15

- Wang, Xiaoming; and Tedford, Richard H. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. p15-7

- Bastl, Katharina Anna (2013). "First evidence of the tooth eruption sequence of the upper jaw in Hyaenodon (Hyaenodontidae, Mammalia) and new information on the ontogenetic development of its dentition". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 88 (4): 481–494. doi:10.1007/s12542-013-0207-z.

- Laudet, V.; Grohé, C.; Morlo, M.; Chaimanee, Y.; Blondel, C.; Coster, P.; Valentin, X.; Salem, M.; Bilal, A. A.; Jaeger, J.-J.; Brunet, M. (2012-11-21). "New Apterodontinae (Hyaenodontida) from the Eocene Locality of Dur At-Talah (Libya): Systematic, Paleoecological and Phylogenetical Implications". PLoS ONE. 7 (11): e49054. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049054. PMC 3504055. PMID 23185292.

- Gheerbrant E, Iarochene M, Amaghzaz M, Bouya B. Geol Mag. 2006;143:475–489.

- Floréal Solé & Thierry Smith, Dispersals of placental carnivorous mammals (Carnivoramorpha, Oxyaenodonta & Hyaenodontida) near the Paleocene-Eocene boundary: a climatic and almost worldwide story, GEOLOGICA BELGICA (2013) 16/4: 254-261

- "HYAENODONTS AND CARNIVORANS FROM THE EARLY OLIGOCENE TO EARLY MIOCENE XIANSHUIHE FORMATION, LANZHOU BASIN, GANSU PROVINCE, CHINA"

- "New Remains of Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) From the Oligocene of Central Mongolia" "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-08. Retrieved 2008-05-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Morlo, M.; Gunnell, G.; Polly, P.D. (2009). "What, if not nothing, is a creodont? Phylogeny and classification of Hyaenodontida and other former creodonts". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (Supplement 3): 152A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2009.10411818.

- Polly, P.D. (1994). "What, if anything, is a creodont?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (Supplement 3): 42A. doi:10.1080/02724634.1994.10011592.

- Polly, P.D. (1996). "The skeleton of Gazinocyon vulpeculus gen. et comb. nov. and the cladisitic relationships of Hyaenodontidae (Eutheria, Mammalia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (2): 303–319. doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011318.

- Grohé et al. 2012

- Halliday, Thomas J. D.; Upchurch, Paul; Goswami, Anjali (2015). "Resolving the relationships of Paleocene placental mammals" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 92: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/brv.12242. ISSN 1464-7931. PMC 6849585. PMID 28075073.

- The Paleobiology Database Hyaenodontidae page

- Solé, F.; Falconnet, J.; Yves, L. (2014). "New proviverrines (Hyaenodontida) from the early Eocene of Europe; phylogeny and ecological evolution of the Proviverrinae". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 171: 878–917. doi:10.1111/zoj.12155.

- Solé, F; Amson, E; Borths, M; Vidalenc, D; Morlo, M; Bastl, K (2015). "A New Large Hyainailourine from the Bartonian of Europe and Its Bearings on the Evolution and Ecology of Massive Hyaenodonts (Mammalia)". PLoS ONE. 10 (9): e0135698. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135698. PMC 4580617. PMID 26398622.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyaenodontidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Hyaenodontidae |