Hyaenodon

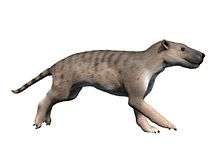

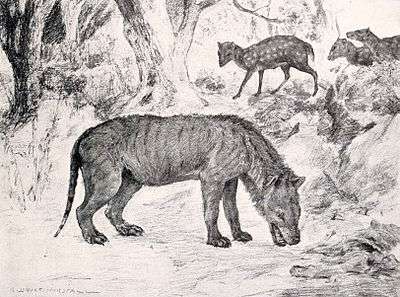

Hyaenodon ("hyena-tooth") is the type genus of the Hyaenodontidae, a family of extinct carnivorous fossil mammals from Eurasia, North America, and Africa, with species existing temporally from the Eocene until the middle Miocene, existing for about 26.1 million years.[1]

| Hyaenodon | |

|---|---|

| H. horridus, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Creodonta |

| Family: | †Hyaenodontidae |

| Genus: | †Hyaenodon |

| Type species | |

| †Hyaenodon leptorhynchus Laizer and Parieu, 1838 | |

| Species | |

|

List

| |

The various species of Hyaenodon competed with each other and with other hyaenodont genera (including Sinopa, Dissopsalis, and Hyainailurus), and played important roles as predators in ecological communities as late as the Miocene in Africa and Asia and preyed on a variety of prey species such as primitive horses like Mesohippus and early camels.[2] Species of Hyaenodon have been shown to have successfully preyed on other large carnivores of their time, including a nimravid ("false sabertooth cat"), according to analysis of tooth puncture marks on a fossil Dinictis skull found in North Dakota.[3]

Description

Some species of this genus were among the largest terrestrial carnivorous mammals of their time; others were only of the size of a marten. Remains of many species are known from North America, Europe, and Asia.[4]

Typical of early carnivorous mammals, individuals of Hyaenodon had a very massive skull, but only a small brain. The skull is long with a narrow snout - much larger in relation to the length of the skull than in canine carnivores, for instance. The neck was shorter than the skull, while the body was long and robust and terminated in a long tail.

The average weight of adult or subadult H. horridus, the largest North American species, is estimated to about 40 kg (88 lb) and may not have exceeded 60 kg (130 lb). H. gigas, the largest Hyaenodon species, was much larger, being 500 kg (1,100 lb) and around 10 feet (3.0 m).[5] H. crucians from the early Oligocene of North America is estimated to only 10 to 25 kg (22 to 55 lb). H. microdon and H. mustelinus from the late Eocene of North America were even smaller and weighed probably about 5 kg (11 lb).[6]

Compared to the generally larger (but closely related) Hyainailouros, the dentition of Hyaenodon was geared more towards shearing meat and less towards bone crushing.[2]

Tooth eruption

Studies on juvenile Hyaenodon specimens show that the animal had a very unusual system of tooth replacement. Juveniles took about 3–4 years to complete the final stage of eruption, implying a long adolescent phase. In North American forms, the first upper premolar erupts before the first upper molar, while European forms show an earlier eruption of the first upper molar.[7]

Range and species

In North America the last Hyaenodon, in the form of H. brevirostris, disappeared in the late Oligocene. In Europe, they had already vanished earlier in the Oligocene.[4]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyaenodon. |

References

- PaleoBiology Database: Hyaenodon, basic info

- Wang, Xiaoming; and Tedford, Richard H. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.p17

- Hoganson, John W; and Person, Jeff. "Tooth puncture marks on a 30 million year old Dinictis skull." Geo News. July 2011. p12-17.

- Wang, Xiaoming, Qiu, Zhanxiang, and Wang, Banyue, 2005. Hyaenodonts and Carnivorans from the Early Oligocene to Early Miocene of Xianshuihe Formation, Lanzhou Basin, Gansu Province, China, Palaeontologia Electronica Vol. 8, Issue 1; 6A: 14p, online

- WANG X. & TEDFORD R. H. 2008. — Dogs, their fossil relatives and evolutionary history. Columbia University Press: 1-219.

- Naoko Egi (2001) Body Mass Estimates in Extinct Mammals from Limb Bone Dimensions: the Case of North American Hyaenodontids _Palaeontology 44 (3) , 497–528 doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00189

- Katharina Anna Bastl, First evidence of the tooth eruption sequence of the upper jaw in Hyaenodon (Hyaenodontidae, Mammalia) and new information on the ontogenetic development of its dentition, Paläontologische Zeitschrift (Impact Factor: 1.1). 10/2013; 88:481-494. DOI: 10.1007/s12542-013-0207-z