Hurricane Ida

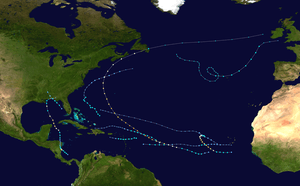

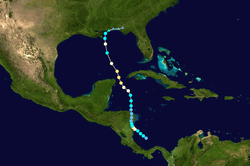

Hurricane Ida was the strongest landfalling tropical cyclone during the 2009 Atlantic hurricane season, crossing the coastline of Nicaragua with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). The remnants of the storm became a powerful nor'easter that caused widespread damage along coastal areas of the Mid-Atlantic States. Ida formed on November 4 in the southwestern Caribbean, and within 24 hours struck the Nicaragua coast with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). It weakened significantly over land, although it restrengthened in the Yucatán Channel to peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). Hurricane Ida weakened and became an extratropical cyclone in the northern Gulf of Mexico before spreading across the southeastern United States. The remnants of Ida contributed to the formation of a nor'easter that significantly affected the eastern coast of the United States.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Ida near peak intensity in the Yucatán Channel on November 8 | |

| Formed | November 4, 2009 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 10, 2009 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 975 mbar (hPa); 28.79 inHg |

| Fatalities | 4 direct |

| Damage | $11.4 million (2009 USD) |

| Areas affected | Central America, Cayman Islands, Yucatán Peninsula, Cuba, Southeastern United States, Mid-Atlantic states, New England, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 2009 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Numerous watches and warnings were issued during the hurricane's existence. Areas from Panama to Maine were affected by either the storm or the nor'easter low. In Nicaragua, nearly 3,000 people evacuated coastal areas ahead of the storm. More extensive evacuations in Mexico relocated over 100,000 residents and tourists. In the United States, several parishes in Louisiana and counties in Alabama and Florida declared a state of emergency because of fear of significant damage from the storm. Officials issued voluntary evacuations and most schools and non-emergency offices in the region closed.

In Central America, Ida brought heavy rainfall to parts of Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Honduras. Several people were reported missing in Nicaragua, however post-storm reports denied these claims. Thousands of buildings collapsed or sustained damage and roughly 40,000 people were left homeless. Damages from Ida in Nicaragua amounted to at least 46 million córdoba ($2.12 million US$). Aside from heavy rainfall in Mexico and Cuba, little impact from Ida was reported in either country. In the United States, the remnants caused substantial damage, mainly in the Mid-Atlantic States. One person was killed by Ida after drowning in rough seas, while six others lost their lives in various incidents related to the nor'easter. Widespread heavy rainfall led to numerous reports of flash flooding in areas from Mississippi to Maine. Overall, the two systems caused nearly $300 million in damage throughout the country.

Meteorological history

Hurricane Ida originated from a weak tropical wave that reached the western Caribbean on November 1, 2009. By November 2, the system spawned an area of low pressure north of Panama which moved very little over the following days. The low became increasingly organized within a favorable environment that allowed deep convection to develop. By November 4, the low had become sufficiently organized for the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to classify it as Tropical Depression Eleven. At this time, the tropical depression was situated just southwest of San Andrés Island.[1] Convective banding features became increasingly defined throughout the day,[2] and six hours after becoming a tropical depression, the system intensified into Tropical Storm Ida.[1]

Light wind shear allowed Ida to quickly intensify as it slowly tracked towards the Nicaraguan coastline.[1] Late on November 4, microwave satellite imagery depicted an eye-like featured forming within the storm. The storm tracked west-northwestward in response to a weak ridge over the north-central Caribbean Sea and a weak trough over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico; these features were also responsible for Ida's slow forward motion.[3] Early on November 5, the storm intensified into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale as it passed near the Corn Islands. At approximately 1117 UTC, the center of Ida made landfall near Rio Grande, Nicaragua, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[4] After the hurricane moved inland, the high mountains of Nicaragua caused the convection associated with the hurricane to diminish, resulting in rapid weakening. Roughly 18 hours after landfall, Ida weakened to a tropical depression as it turned northward over Honduras.[1]

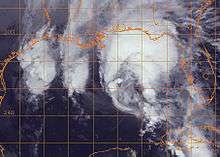

Late on November 6, Ida re-emerged over water, entering the northwestern Caribbean Sea. Upon moving back over water, the storm quickly began to redevelop, with convection increasing around the center of circulation.[5] Early on November 7, Ida restrengthened into a tropical storm as it tracked just west of due north.[1] Very warm sea surface temperatures ahead of the system would have allowed for substantial intensification; however, wind shear over the area quickly increased, resulting in modest strengthening.[6] Later that day, the storm turned northwestward in response to a strong trough over Mexico and a mid-level ridge extending from the Southeast United States to Hispaniola.[7] As Ida neared the Yucatán Channel, an eye redeveloped and the storm quickly intensified into a hurricane. By the morning of November 8, the storm had attained Category 2 status with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h).[1]

Late on November 8, Ida attained its peak intensity with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 975 mbar (hPa; 28.79 inHg). Shortly thereafter, increasing wind shear and forward speed caused the storm to rapidly weaken to a tropical storm.[1] Only a small area of convection remained near the center by the morning of November 9.[8] Despite the strong shear, the storm quickly re-organized, attaining hurricane status for a third time during the afternoon. Based on readings from a nearby oil platform and reconnaissance data, it was determined that Ida attained its secondary peak intensity near the southeast coast of Louisiana with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). However, this intensification was short-lived as a combination of increasing wind shear and decreasing sea-surface temperatures induced weakening to a tropical storm within three hours.[1]

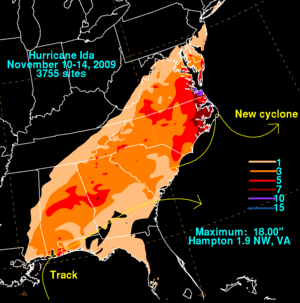

By the morning of November 10, all of Ida's convection appeared displaced to the northeast and the forward motion of the storm slowed substantially. Additionally, the storm had begun to undergo an extratropical transition near the United States Gulf Coast.[9] Shortly before making landfall near Dauphin Island, Alabama,[10] the storm completed its extratropical transition. Ida crossed Mobile Bay shortly thereafter and maximum winds decreased below gale-force. After slowly tracking eastward for several hours, the surface circulation of Ida dissipated over the Florida Panhandle, late on November 10. However, energy from the storm led to the formation of a new low off the coast of North Carolina. This new low quickly intensified and became a powerful nor'easter that caused substantial damage throughout the Mid-Atlantic States.[1] By November 12, the system attained a minimum pressure of 992 mbar (hPa; 29.29 inHg) along with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h).[11] The extratropical low weakened the following day and moved out to sea after stalling along the North Carolina Coastline. The remnants of the cyclone persisted through November 17, by which time it had moved over Atlantic Canada.[12]

Preparations

Central America

Shortly after being designated as Tropical Storm Ida on November 4, the government of Nicaragua issued a tropical storm warning for the entire coastline of Nicaragua, and the government of Columbia also issued a warning for the nearby islands of San Andrés and Providencia. Later that day, a hurricane watch was declared for areas between Bluefields and the Nicaragua–Honduras border. As Ida moved closer to land, the tropical storm warning for San Andrés and Providencia was discontinued. Several hours later, the tropical storm warning and hurricane watch were modified to cover areas south of the Nicaragua–Honduras border to Puerto Cabezas and a hurricane warning was issued for areas south of Puerto Cabezas to Bluefields. After Ida made landfall in Nicaragua, all hurricane advisories were discontinued and replaced by a tropical storm warning. Shortly thereafter, a tropical storm watch was declared for areas along the Honduran coastline between Limón and the Nicaragua–Honduras border. However, all watches and warnings were discontinued once Ida weakened to a tropical depression on November 6.[1]

Throughout Nicaragua, officials evacuated roughly 3,000 people from areas prone to flash floods and landslides, as rainfall in excess of 20 in (510 mm) was expected to fall. About 1,100 of the evacuees were from Corn Island[13] and Little Corn Island where their homes were not expected to hold up to hurricane-force winds. In Bluefields, roughly 1,100 people were evacuated to shelters.[14] Authorities began stockpiling supplies such as food, blankets and water that could supply 20,000 people after the storm.[15] Upon the formation of Ida, officials in Costa Rica placed most northern regions under a yellow alert. Personnel from the Costa Rican Red Cross were also placed on standby.[16] In El Salvador, officials raised the disaster alert level to green, the lowest stage of alert, on November 5.[17] As Ida neared the coastline of Nicaragua, officials in Honduras warned residents of the likelihood of heavy rainfall from the storm. In response to this, the country's disaster alert level was raised to yellow.[18]

Northern Caribbean

| Location | Peak | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| inch | mm | ||

| Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua | 9.1 | 231 | [1] |

| Puerto Lempira, Honduras | 7.1 | 180 | [1] |

| Manuel Lazo, Cuba | 12.5 | 320 | [1] |

| Pensacola, Florida | 5.41 | 137 | [19] |

| Venice, Louisiana | 1.16 | 29.4 | [20] |

| Opelika, Alabama | 9.83 | 250 | [20] |

| Waynesboro, Mississippi | 4.13 | 105 | [20] |

| Lithonia, Georgia | 7.32 | 186 | [21] |

| Mount Le Conte, Tennessee | 4.11 | 104 | [21] |

| Loris, South Carolina | 6.91 | 175 | [21] |

| Manteo, North Carolina | 14.03 | 356 | [21] |

| Hampton, Virginia | 18.00 | 457 | [22] |

| White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia | 2.67 | 67.8 | [22] |

| Washington, D.C. | 1.98 | 50.2 | [22] |

| Assateague Island, Maryland | 7.4 | 187 | [22] |

| Greenwood, Delaware | 4.61 | 117 | [22] |

| Atlantic City, New Jersey | 5.38 | 136 | [22] |

| Holtwood Dam, Pennsylvania | 0.64 | 16.2 | [22] |

| Cullowhee, New York | 3.11 | 78.9 | [22] |

| Wells, Maine | 6.3 | 160 | [23] |

On November 7, Tropical Depression Ida re-entered the Caribbean Sea and restrengthened into a tropical storm, prompting the NHC to issue a tropical storm watch for areas between San Felipe, Yucatán and Punta Allen in Mexico as well as in Pinar del Río Province, Cuba. Several hours later, the watches were upgraded to warnings and a new tropical storm warning was declared for Grand Cayman. A tropical storm watch was also issued for Isla de la Juventud and a hurricane watch for areas between Tulum and Cabo Catoche, Mexico. Early on November 8, the tropical storm warning and hurricane watch for Mexico were modified to include areas from Punta Allen to Playa del Carmen and Tulum to Playa del Carmen respectively. A hurricane warning was also declared for areas between Playa del Carmen and Cabo Catoche. Later that day, the tropical storm warning for Grand Cayman was discontinued as Ida moved away from the island. Early on November 9, all watches and warnings for Cuba and Mexico were discontinued as Ida moved into the Gulf of Mexico and towards the United States.[1]

In Mexico, officials declared a yellow alert, moderate hazard, as Hurricane Ida neared the Yucatán Peninsula on November 9. Roughly 36,000 tourists and 1,500 residents were evacuated from coastal areas of Quintana Roo. The Mexican Navy was placed on standby to assist in relief efforts once the storm had passed.[24] Later that day, the alert was raised to red, the highest level, as hurricane-force winds and heavy rains threatened the region.[25] A total of 95 shelters were opened in the state to house the evacuees.[26]

United States

As Hurricane Ida moved over the Yucatán Channel on November 8, the NHC issued a hurricane watch for areas between Grand Isle, Louisiana and Mexico Beach, Florida. As the storm moved closer to the states, a tropical storm warning was declared for areas between Grand Isle and Pascagoula, Mississippi, as well as areas between Indian Pass, Florida, and the mouth of the Aucilla River. The hurricane watch was also modified to encompass a smaller area, between Grand Isle and Pascagoula. A hurricane warning was also issued from Pascagoula to Indian Pass. During the afternoon of November 9, all hurricane watches and warnings were discontinued and the tropical storm warning was modified to include areas between Grand Isle and the mouth of the Aucilla River. As Ida became extratropical, the NHC discontinued all watches and warnings on the storm on November 10.[1]

Due to the threat of large swells, several oil rigs along the Texas coastline were evacuated as a precautionary measure.[27] Workers from Chevron Corporation and Anadarko Petroleum were evacuated from offshore platforms while those working for ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil remained on site. The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port was also shut down on November 9 as a result of Ida's passage.[28] As a result of the decreased oil production, the price of oil rose more than $1 to $78 per barrel.[29] Among the rigs that were damaged was the Transocean Marianas which was drilling the Macondo well. That vessel would be replaced on the Macondo Well by the Deepwater Horizon, which caused the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010.[30]

On November 8, Lafourche Parish, Louisiana president, Charlotte Randolph, declared a state of emergency for the parish as the storm approached the United States Gulf Coast. Although no evacuations were issued, all schools and government offices were closed through November 10.[31] Voluntary evacuations were issued for residents in Plaquemines Parish along coastal areas. The Belle Chasse Auditorium was converted into a shelter to house evacuees for the duration of the storm.[32] Grand Isle mayor David Carmadelle issued voluntary evacuation orders for residents in recreational vehicles and trailers on the island.[33] Nearly 1,400 families still living in temporary FEMA homes in Louisiana, in the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, were urged to stay at home.[34]

_edit.jpg)

In Baldwin County, Alabama, a local state of emergency was declared on November 9 as Ida neared landfall. Voluntary evacuations were declared for residents living along coastal areas or in mobile homes. All government offices were closed until November 10 due to the storm. The Baldwin County Coliseum was converted into a shelter to house possible evacuees during the storm as well.[35] In Mississippi, officials advised residents to remain vigilant and discussed possible evacuations. Residents living near Pensacola Beach, Florida, and nearby Perdido Key were urged to evacuate.[34] On November 8, emergency officials declared a state of emergency in Escambia County.[36] The following day, Walton County was also placed under a state of emergency ahead of Hurricane Ida's arrival. Voluntary evacuations were issued for residents in low-lying areas and all non-emergency offices were closed until November 10. The Freeport High School gymnasium was converted into a shelter to house evacuees.[37]

Impact and aftermath

Nicaragua

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 1597 | 62.87 | Mitch 1998 | Picacho/Chinandega | [38] |

| 2 | 1447 | 56.97 | Aletta 1982 | Chinandega | [39] |

| 3 | 500 | 19.69 | Joan 1988 | [40] | |

| 4 | 447 | 17.60 | Gert 1993 | Chinandega | [39] |

| 5 | 368 | 14.49 | Fifi 1974 | Chinandega | [39] |

| 6 | 298 | 11.72 | Alma 2008 | Punto Sandino | [41] |

| 7 | 272 | 10.70 | Cesar 1996 | Bluefields | [42] |

| 8 | 231 | 9.10 | Ida 2009 | Puerto Cabezas | [43] |

| 9 | 181 | 7.11 | Felix 2007 | Puerto Cabezas | [44] |

| 10 | 162 | 6.39 | Beta 2005 | Puerto Cabezas | [45] |

Throughout Nicaragua, rainfall produced by the storm was significantly less than anticipated according to satellite derived estimates.[46] Initial fears were that more than 15 in (380 mm) of rain would fall; however, most areas received less than 5 in (130 mm), especially further inland.[46] A maximum of 9.1 in (230 mm) fell in Puerto Cabezas[1] while areas further inland received less than 8 in (200 mm).[46] The most severe damage took place in Karawala and Corn Island, near where the storm made landfall. There, roughly 80 percent of the structures were destroyed and over 2,000 ha (4,900 acres) of crops were lost.[14][47] On Corn Island, 40 homes, 3 schools and a church were destroyed and the electrical and water grids were severely disrupted. Roughly 6,000 people from the municipalities of Sandy Bay, Karawala, Kukra Hilla, Laguna de Perlas, El Tortuguero and the mouth of the Rio Grande were evacuated to 54 shelters during the storm. Officials stated that 42 people along the Miskito Coast were unaccounted for as they refused to evacuate before the storm.[15] The day after Ida passed through, officials began to assess the full extent of the hurricane's damage. An estimated 40,000 people were left homeless throughout the country and one person was listed as missing. Mayors of severely affected towns reported that there were numerous injuries, missing persons and extensive property damage.[48] In Nicaragua, there were no confirmed fatalities as a result of Ida.[1]

Damage from Ida in Nicaragua was estimated to be at least 46 million Nicaraguan córdoba (US$2.12 million).[47][49] A total of 1,334 people were injured by the storm throughout the country.[50] Final damage assessments from the Nicaraguan Government for mainland Nicaragua were completed on November 12. A government report said that 283 homes were destroyed and 1,899 others damaged; 1,184 latrines were destroyed and 444 were damaged, and 476 wells were destroyed and 1,139 were damaged.[51]

Shortly after the storm moved inland, 700 civil defense personnel were deployed to the affected region; however, due to damaged roads and poor travel conditions, they struggled to reach isolated regions.[15] The Nicaraguan army supplied relief crews with four helicopters and two AN-2 aircraft for damage surveillance and search-and-rescue missions in the wake of Ida.[52] The government of Nicaragua allocated roughly $4.4 million in relief funds for those affected by the storm.[47] Several agencies from the United Nations provided residents affected by the storm with relief supplies and donated disaster funds to the country. The United Nations Population Fund provided $49,000 in funds; the World Food Programme deployed several rescue vehicles and logistics teams; UNICEF also provided logistics assistance in the country.[53] OCHA provided $2 million in relief funds; the Government of Sweden provided 400,000 Swedish kronor (US$55,946) for sanitation and health supplies; the Netherlands Red Cross also donated 20,000 euros (US$27,226) for non-food items.[54]

Elsewhere in Central America

In Costa Rica, the outer bands of Ida brought torrential rainfall, triggering isolated landslides. One of these landslides damaged three homes, leading to officials evacuating five families. Homes near Los Diques de Cartago were flooded and the sewage system was damaged, resulting in overflow.[55] In Veraguas Province, Panama, severe flooding displaced more 400 people after 84 homes were inundated up to their roofs.[56] A flooding disaster that killed 124 people in El Salvador was initially attributed to Hurricane Ida, although the National Hurricane Center quickly affirmed that the event resulted from a separate tropical low-pressure system in the Pacific.[1][57] After weakening to a tropical storm, Ida moved over Honduras, where widespread heavy rains fell. A maximum rainfall of 7.1 in (180 mm) was recorded in Puerto Lempira.[1] These rains caused some rivers in the country to swell, but none overflowed its banks.[58] In northern areas of Honduras, minor flooding and fallen trees were reported.[59]

Northern Caribbean

In Cuba, the outer bands of Ida produced widespread heavy rainfall across western areas of the country. A maximum rainfall amount of 12.5 in (320 mm) fell in Manuel Lazo, while nearby areas received between 7 and 9 in (180 and 230 mm).[1] Strong winds, gusting up to 87 mph (140 km/h) in localized areas, accompanied the storm during its passage.[60] Several rivers were swollen due to the rains,[61] including the Cuyaguateje River, which overflowed its banks and flooded nearby areas.[62] In the Yucatán Peninsula, significantly less rain fell due to the asymmetrical structure of Ida even though the peninsula was relatively close to the storm.[1] Isla Holbox, recorded substantial flooding, with roughly 70 percent of the island underwater. However, only minor damage was reported.[63] Little to no beach erosion was sustained in coastal cities such as Cancún; however, over 50,000 tourists were evacuated from Chetumal, Quintana Roo, during the storm.[61] The outer bands of Hurricane Ida also affected Grand Cayman. Moderate rainfall and gusty winds were reported across the island, and waves along the beach were estimated at 6 ft (1.8 m).[64]

United States

Ahead of Ida's arrival in the United States, a tight pressure gradient between the hurricane and a high pressure system over the southeastern states resulted in strong winds across southern Florida. These winds, reaching 45 mph (75 km/h) in gusts, caused moderate damage in parts of the state. Roughly 3,000 people were left without power in Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties. Several trees were reported to have been downed and some uprooted. One car was struck by a broken tree limb during the event. In the Gulf Stream, the 27' Columbia sailing vessel Serenity, was caught the cyclone 150 miles (241 kilometers) north-east of Jacksonville, Florida, and reported a brief strengthening of the storm, with sustained winds of 95 mph (152 km/h), gusting to 110 mph (177 km/h), on the eastern side of the system. Due to the sailing vessels non-response to VHF communications, a USCG helicopter was despatched a short while before the eye of the system arrived in the area. However, the crew refused evacuation, and later managed to arrive, somewhat damaged, in St. Augustine. Additionally, moderate beach erosion was reported in counties along the Gulf Coast.[65] Rainfall from the system impacted Florida for two days, resulting in accumulations between 3 and 5 in (76 and 127 mm) in parts of the panhandle.[66] A maximum rainfall of 5.41 in (137 mm) fell in Pensacola.[19] Coastal and inland flooding resulted in numerous road closures and schools and non-governmental offices were closed on November 10.[66] Water rise along the coast was estimated between 3 and 5 ft (0.91 and 1.52 m) at the height of the storm.[67] Following the storm, a local state of emergency was declared in Wakulla County. Throughout Florida, damage from the storm amounted to $265,000.[65][66][67]

In Alabama, where Ida made landfall, heavy rains resulted in widespread flash flooding.[1] A maximum of 9.83 in (250 mm) of rain fell in Opelika during the storm.[20] Several roads in coastal counties were closed after being covered by high water.[68][69] Heavy rains in central areas of the state also resulted in moderate flooding. In Calhoun County, a three-block area of Anniston was inundated by 2.5 ft (0.76 m) of water.[70] In addition to the storm's heavy rains, waves up to 20 ft (6.1 m) caused severe damage along coastal regions.[71] A storm surge of 4.38 ft (1.34 m) was recorded at Bayou La Batre.[72] The Gulf State Park Pier near Gulf Shores, recently re-opened after being destroyed by Hurricane Ivan in 2004, was damaged. Damage from beach erosion and coastal resorts amounted to roughly $9 million in the state.[71]

Before making landfall in Alabama, Hurricane Ida brushed southeastern Louisiana, bringing light to moderate rains and increased surf to the state. Offshore, one person drowned after attempting to assist a boat that let out a distress signal during the storm.[1] The rough seas resulted in moderate to severe beach erosion that caused roughly 1,000 ft (300 m) of levee to collapse. The levee collapse led to minor flooding and threatened three homes. The storm cut a new pass through Elmer's Island to Grand Isle between 100 and 200 ft (30 and 61 m) wide. A maximum sustained wind of 62 mph (99 km/h) and a gust of 74 mph (119 km/h) was recorded at the mouth of the Mississippi River.[73] The highest rainfall total was recorded in Venice at 1.16 in (29 mm).[20] Although not solely caused by Ida, high tides along the Texas coastline led to a few road closures.[74]

Minor effects from Ida were also experienced in Mississippi, Georgia and Tennessee.[12] In Mississippi, 4.13 in (105 mm) of rain fell in Waynesboro. Some flooding was reported in areas near the Alabama border while winds of up to 45 mph (75 km/h) brought down trees. Along the coast, the hurricane's storm surge was estimated at between 3 and 3.5 ft (0.91 and 1.07 m).[75] Heavy rainfall from the storm affected much of Georgia, with a large swath of 3 to 5 in (76 to 127 mm) falling in northern parts of the state.[12] A peak of 7.32 in (186 mm) was recorded in Lithonia.[21] Additionally, minor rains affected parts of eastern Tennessee,[12] totaling 4.11 in (104 mm) on Mount Le Conte.[21]

Nor'easter

Along the east coast of the United States, a nor'easter involving the remnants of Ida resulted in widespread damage along coastal areas.[1] In North Carolina strong winds downed several trees loosened in saturated soil. In Rockingham County, one person was killed after being struck by a branch while driving.[76] Four homes were destroyed along the Outer Banks, and over 500 others were damaged, leaving at least $5.8 million in losses.[77] Widespread coastal damage and flooding took place in Virginia, as rainfall exceeding 7 in (180 mm) fell in many places and large waves battered beaches.[12][1] In some areas, roads were closed multiple times due to flooding. Minor damage was also reported as a few homes were inundated with up to 1 ft (0.30 m) of water. Some areas reported a storm surge comparable to that of Hurricanes Gloria in 1985 and Isabel in 2003.[78] Damage from the storm in Virginia was estimated to be at least $38.8 million, of which $25 million was in Norfolk alone.[11] In New York, one person drowned after being caught in rough seas off Rockaway Beach.[79] Total beach losses in the state reached $8.2 million.[80]

See also

References

- Avila, Lixion A.; Cangialosi, John (January 14, 2010). "Hurricane Ida Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Blake, Eric; Franklin, James (November 4, 2010). "Tropical Depression Eleven Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Pasch, Richard; Roberts, David (November 4, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ida Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Brown/Blake. "Hurricane Ida Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- Berg, Robbie (November 6, 2009). "Tropical Depression Ida Discussion Eleven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Brennan, Michael (November 7, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ida Discussion Twelve". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Berg, Robbie; James Franklin (November 7, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ida Discussion Fifteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- James, Franklin (November 9, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ida Discussion Twenty-Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- Brennan, Michael (November 10, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ida Discussion Twenty-Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- Brennan, Michael; Blake, Eric; Cangialosi, John (November 10, 2009). "Tropical Storm Ida Public Advisory Twenty-Six-A". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- "Hurricane Season 2009: Ida the Coastal Low". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. December 4, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Roth, David M. (2010). "Hurricane Ida – November 10–14, 2009". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 5, 2009). "Hurricane Ida downgraded, hits thousands in Nicaragua". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Aleman, Filadelfo (November 5, 2009). "Hurricane Ida hits Nicaragua coast". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Staff Writer (November 5, 2009). "Hurricane Ida hits Nicaragua's Caribbean coast – Summary". Earth Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Notimex (November 5, 2009). "Moviliza Costa Rica personal de emergencias por huracán Ida" (in Spanish). Publimetro. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Jovel, Stefany (November 5, 2009). "Protección civil declara alerta verde por huracán Ida". La Prensa Gráfica (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- Staff Writer (November 6, 2009). "Olancho, Colón y Gracias a Dios en alerta amarilla por depresión tropical "Ida"". La Tribuna (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in Florida". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- Roth, David M. (2010). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Maine Event Report: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- EFE (November 9, 2009). "El huracán "Ida" pasó por México sin causar estragos y enfila hacia EE.UU" (in Spanish). ABC Periódico Electrónico. Retrieved February 25, 1010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Decreta México alerta máxima por huracán "Ida"" (in Spanish). Pueblo en Línea. Reuters. November 9, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Agence-France-Presse (November 8, 2009). "México se mantiene alerta ante el paso cercano del hucarán Ida". La Tribuna (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "Obliga Ida a evacuar plataformas petroleras en Golfo de México" (in Spanish). Enterate Tabasco. November 9, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Seba, Erwin; Nichols, Bruce (November 8, 2009). "Oil companies pull workers, shut port ahead of Ida". Reuters. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 8, 2009). "Oil jumps $1 to above $78 on hurricane fears, dollar". Alibaba. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- "Letter from Henry Waxman to Tony Hayward – June 14, 2010" (PDF). nergycommerce.house.gov. June 14, 2010. Archived from the original (press release) on December 7, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- Luke, Michael (November 10, 2009). "Lafourche: Calls state of emergency, closes schools, no evacuation called". WWLTV. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Luke, Michael (November 8, 2009). "Plaquemines schools closed because of Ida; voluntary evacuation for parts of parish". WWLTV. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 8, 2009). "Voluntary evacuation of Grand Isle RVs". WWL. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Laboy, Suzette; Shoichet, Catherine E. (November 9, 2009). "Hurricane Ida weakens, but Gulf still on warning". The Guardian. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 9, 2009). "County prepares for Hurricane Ida". Baldwin County Now. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Petri, Chad. "Escambia County Florida Prepares For Ida". WKRG. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- Florida Freedom Newspapers (November 9, 2009). "Ida closes schools, government as county gears up for tropical storm (3p.m. Update)". The Walton Sun. Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- U. S. Geological Survey. "Landslide Response to Hurricane Mitch Rainfall in Seven Study Areas in Nicaragua" (PDF). Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- Dr. Wilfried Strauch (November 2004). "Evaluación de las Amenazas Geológicas e Hidrometeorológicas para Sitios de Urbanización" (PDF). Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER). p. 11. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- "Nicaragua - Hurricane Joan". ReliefWeb. October 26, 1988. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- Daniel P. Brown. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Alma" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Lixion Avila. "Preliminary Report: Hurricane Cesar - 24-29 July 1996" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Lixion A. Avila and John Cangialosi (January 14, 2010). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ida" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- Jack Beven. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Felix" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- Richard J. Pasch and David P. Roberts. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Beta - 26-31 October 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Masters, Jeff (November 7, 2009). "Ida strengthens, could be a hurricane for the Yucatan". Weather Underground. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- Pérez, César y Cajina, Jairo (2009). "Huracán Ida" (in Spanish). La Voz Del Sandinismo. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Staff Writer (November 6, 2009). "El huracán 'Ida' deja al menos 40.000 damnificados en Nicaragua" (in Spanish). Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- León, Sergio (November 5, 2009). "Huracán deja estela de daños en la RAAS" (in Spanish). La Prensa. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Missair, Alfredo (November 11, 2009). "Informe de Situación # 6" (PDF) (in Spanish). Red Humanitaria. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- De Nicaragua, Ejército (November 12, 2009). "Defensa Civil Matriz de afectaciones por Municipios afectados Huracán Ida" (PDF) (in Spanish). Red Humanitaria. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- "Huracán Ida toca tierra en Nicaragua". El Universal (in Spanish). Associated Press. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Mortensen, Thomas Fogh (November 30, 2009). "Emergencia por el Huracán Ida: Recursos de Organizaciones" (PDF) (in Spanish). Red Humanitaria. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- Mortensen, Thomas Fogh (November 25, 2009). "Informe de Situación # 10" (PDF) (in Spanish). Red Humanitaria. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- Vanessa Loaiza N. (November 5, 2009). "Huracán Ida obliga a evacuar familias en Guararí" (in Spanish). Natión. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Staff Writer (November 5, 2009). "Tormenta Ida toca tierra firme en Nicaragua" (in Spanish). La Prensa. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- "El Salvador flooding death toll rises to 124". CBC News. Associated Press. November 8, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- Latina, Prensa (November 7, 2009). "La depresión tropical Ida abandona Honduras dejando lluvias en la región caribeña" (PDF) (in Spanish). Centro Nacional de Información de Ciencias Médicas. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 6, 2009). ""Ida" se degrada a depresión tropical" (in Spanish). El Heraldo. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- "El huracán Ida deja fuertes lluvias en Pinar del Río" (in Spanish). Cuban En Cuentro. November 9, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- González, Carlos Alberto Santamaría (November 9, 2009). "Especial por el huracán Ida" (PDF) (in Spanish). Boletín de noticias sobre clima, tiempo y salud. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- Padilla, Abel Padrón (November 9, 2009). "Ida deja inundaciones en Pinar del Río" (in Spanish). Cuba Debate. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- Cárdenas, Lázaro (November 9, 2009). "Regresan evacuados a Holbox" (in Spanish). Noticaribe. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Staff Writer (November 8, 2009). "Update: Grand Cayman in clear". Cay Compass News Online. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- "Florida Event Report: Strong Wind". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Florida Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Florida Event Report: Coastal Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Alabama Event Report: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Alabama Event Report: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Alabama Event Report: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Alabama Event Report: High Surf". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Alabama Event Report: Storm Tide". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Louisiana Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Texas Event Report: Coastal Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Mississippi Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "North Carolina Event Report: Strong Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "North Carolina Event Report: Coastal Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "Virginia Event Report: Coastal Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "New York Event Report: High Surf". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- "New York Event Report: High Surf". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Ida (2009). |

- The National Hurricane Center's Advisory Archive for Hurricane Ida

- The Hydrometeorological Prediction Center's Advisory Archive for the remnants of Hurricane Ida

- The National Hurricane Center's Tropical Cyclone Report on Hurricane Ida

- The Hydrometeorological Prediction Center's Report on Hurricane Ida

- (in Spanish) Emergency reports for Central America related to Hurricane Ida and the El Salvador floods and mudslides

- The National Climatic Data Center's Storm Event Database