Tropical Storm Aletta (1982)

Tropical Storm Aletta was a weak but destructive tropical storm that killed 308 people while meandering off the coast of Central America in May 1982. An area of disturbed weather developed into a tropical depression on May 20, and into a tropical storm around noon on May 21. The cyclone turned northeast, reaching its peak as a strong tropical storm on May 23. Aletta meandered and gradually weakened, dissipating a few hundred miles southwest of Acapulco on May 29. Moisture from the tropical system spread over Honduras and Nicaragua, causing flooding. Throughout the two countries, 308 people were killed and total damage was at $466 million (1982 USD). In the aftermath of the storm, many programs provided relief to the victims of Aletta.

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

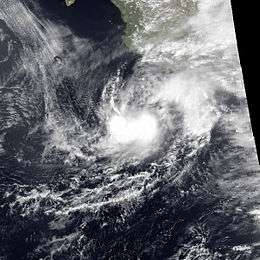

Tropical Storm Aletta on May 21, 1982 | |

| Formed | May 20, 1982 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | May 29, 1982 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 65 mph (100 km/h) |

| Fatalities | 308 dead, 275 missing |

| Damage | $466 million (1982 USD) |

| Areas affected | Honduras, Nicaragua |

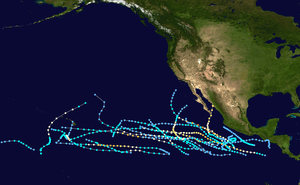

| Part of the 1982 Pacific hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

The origins of Aletta are from a tropical disturbance that was first noted on May 18 about 500 mi (800 km) south-southwest of Acapulco. On May 20, satellite imagery showed evidence of a weak atmospheric circulation. Based on this, the disturbance was upgraded into a tropical depression. Moving northwest, the depression became Tropical Storm Aletta 36 hours later over 86 °F (30 °C) sea surface temperatures. The system re-curved towards the northeast due to strong upper-level westerlies, reaching its peak intensity of 65 mph (100 km/h) on May 23.[1]

Shortly after its peak, Tropical Storm Aletta began to weaken. However, the tropical cyclone managed to maintain winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) for 30 hours before resuming a weakening trend.[2] While the steering currents weakened on May 25, Aletta slowed and moved in a large clockwise loop until May 28. Shortly thereafter, Tropical Storm Aletta was downgraded into a depression. Tropical Depression Aletta dissipated on May 29 roughly 180 mi (290 km/h) southwest of Acapulco.[1]

Impact and aftermath

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 1597 | 62.87 | Mitch 1998 | Picacho/Chinandega | [3] |

| 2 | 1447 | 56.97 | Aletta 1982 | Chinandega | [4] |

| 3 | 500 | 19.69 | Joan 1988 | [5] | |

| 4 | 447 | 17.60 | Gert 1993 | Chinandega | [4] |

| 5 | 368 | 14.49 | Fifi 1974 | Chinandega | [4] |

| 6 | 298 | 11.72 | Alma 2008 | Punto Sandino | [6] |

| 7 | 272 | 10.70 | Cesar 1996 | Bluefields | [7] |

| 8 | 231 | 9.10 | Ida 2009 | Puerto Cabezas | [8] |

| 9 | 181 | 7.11 | Felix 2007 | Puerto Cabezas | [9] |

| 10 | 162 | 6.39 | Beta 2005 | Puerto Cabezas | [10] |

The outer rainbands of Tropical Storm Aletta produced torrential rains and high winds over Central America for several days,[11][12][13] and precipitation totals were as high as 23.3 in (590 mm) in some areas[14] with a peak of 57.32 in (1,456 mm) in Chinandega.[15] A red cross official stated that "Entire families were swept away by [flood waters] and we know nothing about them". Because all sewers in Nicaragua were damaged, the water was contaminated.[16] Ninety percent of the banana crop and 60 percent of the corn crop was completely destroyed.[11] Throughout the country, 108 people were killed,[13] (10 of which drowned in floodwaters).[14] Roughly 20,000 people were homeless[11] and total damage was estimated at $365 million (1982 USD);[17] damage to highways, factories, and farms exceeded $100 million.[13] In the northern portion of the country, a mudslide buried three small mountain villages, leaving 270 missing and only 29 survivors.[18] About 15,000 sought to two emergency shelters. Many bridges were damaged. Since the capital city of Leon was hardest hit, a disaster area was declared for the nearby area.[14] Aletta was considered the worst disaster in the country in three years.[13]

Across Honduras, 200 people were killed[11] and 5,000 people were without food or water in just 13 communities.[16] A total of 80,000 people were homeless[12] which were later housed in schools, churches, and health victims.[19] Total damage was placed at $101 million (1982 USD).[17]

On May 27, the governments of both Honduras and Nicaragua appealed for international aid. Soldiers quickly sent food and medical to at least 50 communities in both countries.[20] A second appeal was made shortly afterwards, which proposed for $5.1 million in medicine and other supplies.[21] The red cross and United Nations (UN) appealed for $3 million in international relief.[22] The UN granted Nicaragua a month's worth of food supply, but officials feared that this would not be enough.[16] The government of Cuba announced that they would send 12,000 construction workers as well as 2,000 teachers, doctors, and officials to Nicaragua.[23] Canada donated $220,000 via the League of Red Cross Societies.[11] To prevent an epidemic of diseases such as typhoid fever, the Health Ministry started a program to give out vaccines which costs $5.1 million.[13] The U.S. Embassy in Managua provided $25,000 in donations. The U.S. Embassy in Honduras attempted to outline a fact-fining mission to assess the damage and provide relief.[24]

See also

References

- Gunther, Emil B.; R.L. Cross; R. A. Wagoner (May 1983). <1080:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2 "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1982". Monthly Weather Review. 111 (5): 1080–1102. Bibcode:1983MWRv..111.1080G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<1080:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- U. S. Geological Survey. "Landslide Response to Hurricane Mitch Rainfall in Seven Study Areas in Nicaragua" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- Dr. Wilfried Strauch (November 2004). "Evaluación de las Amenazas Geológicas e Hidrometeorológicas para Sitios de Urbanización" (PDF). Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER). p. 11. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- "Nicaragua - Hurricane Joan". ReliefWeb. 1988-10-26. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- Daniel P. Brown. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Alma" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- Lixion Avila. "Preliminary Report: Hurricane Cesar - 24-29 July 1996" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- Lixion A. Avila and John Cangialosi (January 14, 2010). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ida" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- Jack Beven. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Felix" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- Richard J. Pasch and David P. Roberts. "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Beta - 26-31 October 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Canada Aids Victims". The Leader-Post. June 10, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Tropical Storm Leaves 80,000 Homeless In Honduras". Observer-Reporter. Associated Press. May 29, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Nicaragua seeks aid as flood victims kill 108". The Montreal Gazette. May 28, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Nicaragua declares flood disaster". The Telegraph-Herald. May 26, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- Dr. Wilfried Strauch (November 2004). "Evaluación de las Amenazas Geológicas e Hidrometeorológicas para Sitios de Urbanización" (PDF). Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER). p. 11. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- "Killer tropical storm continues". Tri City Herald. May 23, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Tropical Storm Aletta". Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Mudslides hit Nicaragua". The Summer Daily Item. May 31, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Nicaragua asks storm victims aid". St. Joseph News. June 9, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Nicaragua Appeals For Aid As Tropical Storm Kills 17". Observer-Reporter. Associated Press. May 28, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Honduras Appeals Again For Storm Aid". The Pittsburgh Press. Associated Press. May 29, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Canada aids storm victims". Ottawa Citizen. June 10, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Cubans Planning To Aid Nicaragua". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. June 9, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "U.S. eyes on Nicaragua flood aid". The Telegraph-Herald. Retrieved September 18, 2011.