Huế

Huế (Vietnamese: [hwě] (![]()

Hue Huế | |

|---|---|

| Hue | |

.jpg) Tràng Tiền bridge on Perfume River | |

| Nickname(s): City of Romance, Festival City | |

| |

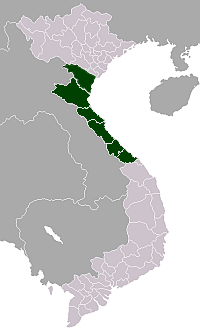

Hue Location of Hue | |

| Coordinates: 16°28′00″N 107°34′45″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Thua Thien-Hue |

| Area | |

| • Total | 70.67 km2 (27.29 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 455,230 |

| • Density | 5,010.9/km2 (12,978/sq mi) |

| Climate | Tropical monsoon climate |

| Website | huecity.gov.vn |

History

The oldest ruins in Hue belong to the Kingdom of Lam Ap, dating back to the 4th century AD. The ruins of its capital, the ancient city of Kandapurpura is now located in Long Tho Hill, 3 kilometers to the west of the city. Another Champa ruin in the vicinity, the ancient city of Hoa Chau is dated back to the 9th century.

In 1306, the King of Champa Che Man offered Vietnam two Cham prefectures, O and Ly, in exchange for marriage with a Vietnamese princess named Huyen Tran.[1] The Vietnamese King Tran Anh Tong accepted this offer.[1] He took and renamed O and Ly prefectures to Thuan prefecture and Hóa prefecture, respectively, with both of them often referred to as Thuan Hoa region.[1][2]

In 1592, the Mac dynasty was forced to flee to Cao Bang province and the Le emperors were enthroned as de jure Vietnamese rulers under the leadership of Nguyen Kim, the leader of Le Dynasty loyalists. Later, Kim was poisoned by a Mạc Dynasty general which paved the way for his son-in-law, Trinh Kiem, to take over the leadership. Kim's eldest son, Nguyen Uông, was also assassinated in order to secure Trinh Kiem's authority.[3] Nguyen Hoang, another son of Nguyen Kim, feared a fate like Nguyen Uong's so he pretended to have mental illness. He asked his sister Ngoc Bao, who was a wife of Trinh Kiem, to entreat Trinh Kiem to let Nguyen Hoang govern Thuan Hoa, the furthest south region of Vietnam at that time.[4]

Because Mac dynasty loyalists were revolting in Thuan Hoa and Trinh Kiem was busy fighting the Mac dynasty forces in northern Vietnam during this time, Ngoc Bao's request was approved and Nguyen Hoang went south.[4] After Hoàng pacified Thuan Hoa, he and his heir Nguyen Phuc Nguyen serectly made this region loyal to the Nguyen family; then they rose against the Trinh Lords.[5][6] Vietnam erupted into a new civil war between two de facto ruling families: the clan of the Nguyen lords and the clan of the Trinh lords.

The Nguyen lords chose Thua Thien, a northern territory of Thuan Hoa, as their family seat.[7] In 1687 during the reign of Nguyen lord- Nguyen Phuc Tran,[8] the construction of a citadel was started in Phu Xuan, a village in Thua Thien Province.[7][8] The citadel was a power symbol of Nguyen family rather than a defensive building because the Trịnh lords' army could not breach Nguyen lords' defense in the north regions of Phú Xuân.[7] In 1744, Phu Xuan officially became the capital of central and southern Vietnam after Nguyen lord- Nguyen Phuc Khoat proclaimed himseft Vo Vương (Vo King or Martial King in Vietnamese).[7] Among westerners living in the capital at this period was the Portuguese Jesuit João de Loureiro from 1752 onwards.[9]

However, Tay Son rebellions broke out in 1771 and quickly occupied a large area from Quy Nhon to Binh Thuan Province, thereby weakening the authority and power of the Nguyen lords.[10] While the war between Tây Sơn rebellion and Nguyễn lord was being fought, the Trịnh lords sent south a massive army and easily captured Phú Xuân in 1775.[11] After the capture of Phú Xuân, the Trịnh lords' general Hoang Ngu Phuc made a tactical alliance with Tay Son and withdrew almost all troops to Tonkin and left some troops in Phu Xuan.[12] In 1786, Tây Sơn rebellion defeated the Trịnh garrison and occupied Phú Xuân.[13] Under the reign of emperor Quang Trung, Phú Xuân became Tây Sơn dynasty capital.[14] In 1802, Nguyen Anh, a successor of the Nguyen lords, recaptured Phu Xuan and unified the country. Nguyen Anh rebuilt the citadel entirely and made it the Imperial City capital of all of Vietnam.[7]

The city's current name is likely a non-Sino-Vietnamese reading of the Chinese 化 (Sino-Vietnamese: hoá), as in the historical name Thuan Hoa (順化).

In 1802, Nguyen Phuc Anh (later Emperor Gia Long) succeeded in establishing his control over the whole of Vietnam, thereby making Hue the national capital.[15]

Minh Mang (r. 1820–40) was the second emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty, reigning from 14 February 1820 (his 29th birthday) until his death, on 20 January 1841. He was a younger son of Emperor Gia Long, whose eldest son, Crown Prince Canh, had died in 1801. Minh Mang was well known for his opposition to French involvement in Vietnam, and for his rigid Confucian orthodoxy.

During the French colonial period, Hue was in the protectorate of Annam. It remained the seat of the Imperial Palace until 1945, when Emperor Bao Dai abdicated and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) government was established with its capital at Ha Noi (Hanoi), in the north.[16]

While Bao Dai was proclaimed "Head of the State of Vietnam" with the help of the returning French colonialists in 1949 (although not with recognition from the communists or the full acceptance of the Vietnamese people), his new capital was Sai Gon (Saigon), in the south.[17]

During the Republic of Vietnam period, Hue, being very near the border between the North and South, was vulnerable in the Vietnam War. In the Tet Offensive of 1968, during the Battle of Hue, the city suffered considerable damage not only to its physical features, but its reputation as well, due to a combination of the American military bombing of historic buildings held by the North Vietnamese, and the massacre at Hue committed by the communist forces.

After the war's conclusion in 1975, many of the historic features of Huế were neglected because they were seen by the victorious communist regime and some other Vietnamese as "relics from the feudal regime"; the Communist Party of Vietnam doctrine described the Nguyen Dynasty as "feudal" and "reactionary". There has since been a change of policy, however, and many historical areas of the city are being restored and the city is being developed as a centre for tourism and transportation for central Vietnam.

Geography

The city is located in central Vietnam on the banks of the Perfume River, just a few miles inland from the East Sea. It is about 700 km (430 mi) south of Hanoi and about 1,100 km (680 mi) north of Ho Chi Minh City. The North and West side borders Huong Tra town; the South borders Huong Thuy town, and the East side borders Phu Vang district and Huong Thuy town. Located on the two banks of the Perfume River or Perfume River downstream, north of Hai Van Pass, 105 km (65 mi) from Danang, 14 km (8.7 mi) from Thuan An Seaport and Phu Bai International Airport and 50 km (31 mi) from Chan May Port. The natural area is 71.68 km2 (27.68 sq mi) and the population in 2012 is estimated at 344,581 people. As of 2018, the city population is 455,230 people (including those who are not registered residents).

Located near Truong Son mountain range, Hue city is a plain area in the lower reaches of the Perfume and Bo rivers, with an average altitude of 3–4 m above sea level and often flooded when the river's headwaters Huong has medium and large rainfall. This plain area is relatively flat, although there are alternating hills and low mountains such as Ngu Binh mountain and Vong Canh[18] Hill.

Climate

Hue features a tropical monsoon climate under the Köppen climate classification, falling short of a tropical rainforest climate because there is less than 60 millimetres (2.4 in) of rain in March and April. The dry season is from April to August, with high temperatures of 35 to 40 °C (95 to 104 °F). The rainy season is from August to January, with a flood season from October, onwards. The average rainy season temperature is 20 °C (68 °F), sometimes as low as 9 °C (48 °F). Spring lasts from February to March .[19]

| Climate data for Hue | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.6 (92.5) |

36.3 (97.3) |

38.6 (101.5) |

39.9 (103.8) |

41.3 (106.3) |

40.7 (105.3) |

39.6 (103.3) |

39.7 (103.5) |

39.7 (103.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

41.3 (106.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.8 (74.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.3 (93.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

29.5 (85.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 126 (5.0) |

65 (2.6) |

43 (1.7) |

58 (2.3) |

102 (4.0) |

113 (4.4) |

92 (3.6) |

117 (4.6) |

394 (15.5) |

757 (29.8) |

621 (24.4) |

311 (12.2) |

2,798 (110.2) |

| Average precipitation days | 14.4 | 11.9 | 10.3 | 10.7 | 13.0 | 10.3 | 8.2 | 11.0 | 16.6 | 20.8 | 21.5 | 19.7 | 168.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 89.0 | 89.4 | 86.9 | 83.8 | 78.9 | 74.6 | 72.9 | 74.9 | 83.2 | 87.4 | 88.8 | 89.2 | 83.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114 | 110 | 147 | 177 | 234 | 231 | 247 | 218 | 173 | 136 | 100 | 85 | 1,970 |

| Source: Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology[20] | |||||||||||||

Government

.jpg)

Administrative divisions

Hue comprises 27 administrative divisions, including 27 phường (urban wards):

- An Cựu

- An Đông

- An Hòa

- An Tây

- Hương Long

- Hương Sơ

- Kim Long

- Phú Bình

- Phú Cát

- Phú Hậu

- Phú Hiệp

- Phú Hòa

- Phú Hội

- Phú Nhuận

- Phú Thuận

- Phước Vĩnh

- Phường Đúc

- Tây Lộc

- Thuận Hòa

- Thuận Lộc

- Thuận Thành

- Thủy Biều

- Thủy Xuân

- Trường An

- Vĩnh Ninh

- Vỹ Dạ

- Xuân Phú

Culture

In the center of Vietnam, Hue was the capital city of Vietnam for approximately 150 years during feudal times (1802–1945),[21] and the royal lifestyle and customs have had a significant impact on the characteristics of the people of Hue. That impact can still be felt today.

Name-giving

Historically, the qualities valued by the royal family were reflected in its name-giving customs, which came to be adopted by society at large. As a rule, royal family members were named after a poem written by Minh Mạng, the second emperor of Nguyen Dynasty. The poem, Đế hệ thi",[22] has been set as a standard frame to name every generation of the royal family, through which people can know the family order as well as the relationship between royal members. More importantly, the names reflect the essential personality traits that the royal regime would like their offspring to uphold. This name-giving tradition is proudly kept alive and nowadays people from Huế royal family branches (normally considered 'pure' Huế) still have their names taken from the words in the poem.

Clothing

The design of the modern-day ao dai, a Vietnamese national costume, evolved from an outfit worn at the court of the Nguyen Lords at Hue in the 18th century. A court historian of the time described the rules of dress as follows:

"Thường phục thì đàn ông, đàn bà dùng áo cổ đứng ngắn tay, cửa ống tay rộng hoặc hẹp tùy tiện. Áo thì hai bên nách trở xuống phải khâu kín liền, không được xẻ mở. Duy đàn ông không muốn mặc áo cổ tròn ống tay hẹp cho tiện khi làm việc thì được phép."

"Outside court, men and women wear gowns with straight collars and short sleeves. The sleeves are large or small depending on the weather. There are seams on both sides running down from the sleeve, so the gown is not open anywhere. Men may wear a round collar and a short sleeve for more convenience."

This outfit evolved into the áo ngũ thân, a five-paneled aristocratic gown worn in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Inspired by Paris fashions, Nguyen Cat Tuong and other artists associated with Hanoi University redesigned the ngũ thân as a modern dress in the 1920s and 1930s.[23] While the ao dai and non la are generally seen as a symbol of Vietnam as a whole, the combination is seen by Vietnamese as being particularly evocative of Hue. Violet-coloured ao dai are especially common in Hue, the color having a special connection to the city's heritage as a former capital.[24][25]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Hue forms the heart of Central Vietnamese cuisine, but one of the most striking differences is the prominence of vegetarianism in the city. Several all-vegetarian restaurants are scattered in various corners of the city to serve the locals who have a strong tradition of eating a vegetarian meal twice a month, as part of their Buddhist beliefs. Another feature of Hue dishes that sets them apart from other regional cuisines in Vietnam is the relatively small serving size with refined presentation, a vestige of its royal cuisine. Hue cuisine is notable for often being very spicy.[26]

Hue cuisine has both luxurious and popular rustic dishes. With such a rich history, Hue's royal cuisine combines both taste and aesthetics. It consists of several distinctive dishes from small and delicate creations, originally made to please the appetites of Nguyen feudal lords, emperors, and their hundreds of concubines and wives.[27]

Besides Bun Bo Hue, other famous dishes includes:

- Bánh bèo is a Vietnamese dish that originally comes from Hue City, Central Vietnam. It is made from a combination of rice flour and tapioca flour. The ingredients include rice cakes, marinated-dried shrimps and crispy pork skin, scallion oil and dipping source. It can be considered as street food, and can eat as lunch or dinner.

- Cơm hến (Baby basket clams rice) is a Vietnamese dish originating in Huế. It is made with baby mussels or basket clams and rice; it is normally served at room temperature.

- Bánh ướt thịt nướng (Steamed rice pancake with grilled pork) is the most well-known dish of people of Kim Long- Huế. The ingredients include steamed rice pancake, vegetables – Vietnamese mint herb, basil leaves, lettuce, cucumber and cinnamon leaves, pork and is served with dipping sauce.

- Bánh khoái (Hue shrimp and vegetable pancake) is the modified form of Bánh xèo. It is deep fried and served with Hue peanut dipping sauce containing pork liver. Its ingredients include egg, liver, prawns and pork belly or pork sausage, and carrot. It is served with lettuce, fresh mint, Vietnamese mint, star fruit, and perilla leaves.

- Bánh bột lọc (Vietnamese clear shrimp and pork dumplings) can be wrapped with or without banana leaf. It is believed to originate from Hue, Vietnam during Nguyen Dynasty. Main ingredients include tapioca flour, shrimps and pork belly; it is often served with sweet chili fish sauce.

- Banh it ram (fried sticky rice dumpling) is a specialty in Central Vietnam. It is the combination of fried sticky rice dumplings which is sticky, soft and chewy, and crispy stick rice cake at the bottom.

Additionally, Hue is also famous for it delicious sweet desserts such as Lotus seeds sweet soups, Lotus seed wrapped in logan sweet soup, Areca flower sweet soup, Grilled pork wrapped in cassava flour sweet soup, and Green sticky rice sweet soup.

Religion

The imperial court practiced various religions such as Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. The most important altar was the Esplanade of Sacrifice to the Heaven and Earth, where the monarch would offer each year prayers to the Heaven and Earth.

In Hue, Buddhism enjoyed stronger support than elsewhere in Vietnam, with more monasteries than anywhere else in the country serving as home to the nation's most famous monks.

In 1963, Thich Quang Duc drove from Hue to Saigon to protest anti-Buddhist policies of the South Vietnamese government, setting himself on fire on a Saigon street. Photos of the self-immolation became some of the enduring images of the Vietnam War.[28]

Thich Nhat Hanh, world-famous Zen master who originates from Hue and has lived for years in exile including France and the United States, has returned to his home town in October 2018 and been residing there since at the Tu Hieu pagoda.[29]

Tourism

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Criteria | Cultural: iv |

| Reference | 678 |

| Inscription | 1993 (17th session) |

| Area | 315.47 ha |

| Buffer zone | 71.93 ha |

Hue is well known for its historic monuments, which have earned it a place in UNESCO's World Heritage Sites.[30] The seat of the Nguyen emperors was the Imperial City, which occupies a large, walled area on the north side of the Perfume River. Inside the citadel was a forbidden city where only the emperors, concubines, and those close enough to them were granted access; the punishment for trespassing was death. Today, little of the forbidden city remains, though reconstruction efforts are in progress to maintain it as a historic tourist attraction.

Roughly along the Perfume River from Hue lie myriad other monuments, including the tombs of several emperors, including Minh Mang, Khai Dinh, and Tu Duc. Also notable is the Thien Mu Pagoda, the largest pagoda in Hue and the official symbol of the city.[31]

A number of French-style buildings lie along the south bank of the Perfume River. Among them are Hue High School for the Gifted, the oldest high school in Vietnam, and Hai Ba Trung High School.

The Huế Museum of Royal Fine Arts on 3 Le Truc Street also maintains a collection of various artifacts from the city.

In addition to the various touristic attractions in Hue itself, the city also offers day-trips to the Demilitarized Zone lying approximately 70 km (43 mi) north, showing various war settings like The Rockpile, Khe Sanh Combat Base or the Vinh Moc tunnels.

Most of the hotels, bars, and restaurants for tourists in Hue are located in Pham Ngu Lao, Chu Van An and Vo Thi Sau street, which together form the backpacker district.

In the first 11 months of 2012, Hue received 2.4 million visitors, an increase of 24.6% from the same period of 2011. 803,000 of those 2.4 million visitors were foreign guests, an increase of 25.7%. Although tourism plays a key role in the city's socioeconomic development, it also has negative impacts on the environment and natural resource base.[32] For example, services associated with tourism, such as travel, the development of infrastructure and its operation, and the production and consumption of goods, are all energy-intensive.[33] Research by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network has identified traditional ‘garden houses’ as having the potential to increase tourist traffic and revenue. Apart from the environmental, economic and cultural benefits provided by garden houses, their promotion could pave the way for other low carbon development initiatives.[34]

Infrastructure

Health

The Hue Central Hospital, established in 1894, was the first Western hospital in Vietnam. The hospital, providing 2078 beds and occupying 120,000 square meters (30 acres), is one of three largest in the country along with Bach Mai Hospital in Hanoi and Cho Ray Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, and is managed by the Ministry of Health.[35]

Transportation

Hue Railway Station provides a rail connection to major Vietnamese cities, via the North-South Railway. Phu Bai International Airport is just south of the city centre.

Sister cities

- Bandar-e Anzali, Iran[36]

- Honolulu, Hawaii, United States[37]

- New Haven, Connecticut, United States[37]

- Blois, France, Centre-Val de Loire, since May 2007[38]

Gallery

.jpg) Entrance of the Imperial City

Entrance of the Imperial City.jpg) Imperial City

Imperial City.jpg) Sightseeing

Sightseeing.jpg) Nine Dynastic Urns

Nine Dynastic Urns.jpg) Staircases at Hiem Lam Cac

Staircases at Hiem Lam Cac.jpg) Imperial City, Gate

Imperial City, Gate.jpg) Lotus lake

Lotus lake.jpg) Mandarin soldiers at Khải Định tomb

Mandarin soldiers at Khải Định tomb Perfume River

Perfume River- Tomb of Emperor Khải Định

Trường Tiền Bridge

Trường Tiền Bridge Thế Miếu temple

Thế Miếu temple Meridian Gate

Meridian Gate Walls of Imperial City of Hue

Walls of Imperial City of Hue

See also

- USS Hue City

- List of historical capitals of Vietnam

References

References

- Chapuis, p.85.

- Phan Khoang, p.85.

- Chapuis, p. 119.

- Phan Khoang, pp.108–110.

- Trần Trọng Kim, pp. 275–276.

- Trần Trọng Kim, pp. 281–283.

- Ring & Salkin & La Boda, pp.362–364.

- Trần Trọng Kim, p. 326

- Nhung Tuyet Tran, Anthony Reid Việt Nam: Borderless Histories 2006 Page 223 "He did not, however, leave Asia, traveling instead around the region collecting botanical species, before eventually returning to Phú Xuân in 1752. He then remained at the Nguyễn political center for the next quarter century, finally leaving at...."

- George Edson Dutton The Tây Sơn Uprising: Society and Rebellion in Eighteenth-century Vietnam 2006 "Phú Xuân"

- Trần Trọng Kim, pp. 337–338.

- Trần Trọng Kim, pp. 339–340

- Trần Trọng Kim, pp. 348–349.

- Largo, p.105.

- Woodside, Alexander (1988). Vietnam and the Chinese model: a comparative study of Vietnamese and Chinese government in the first half of the nineteenth century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- Boobbyer, Claire; Spooner, Andrew; O'Tailan, Jock (2008). Vietnam, Cambodia & Laos. Footprint Travel Guides. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-906098-09-4.

- Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2001). The Encyclopedia of world history: ancient, medieval, and modern, chronologically arranged. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 1036.

- "Vong Canh Hill - Destination for travellers fancy exploring nature". Hue Smile Travel. 21 August 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Ishizawa, Yoshiaki; Kōno, Yasushi; Rojpojchanarat, Vira; Daigaku, Jōchi; Kenkyūjo, Ajia Bunka (1988). Study on Sukhothai: research report. Institute of Asian Cultures, Sophia University. p. 68.

- "Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical & Climatic Data for Construction" (PDF) (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Nguyễn, Dac Xuan (2009). 700 năm Thuan Hoa-Phu Xuan-Hue. Việt Nam: Nhà xuất bản Trẻ.

- vi:Minh Mạng

- Ellis, Claire (1996), "Ao Dai: The National Costume", Things Asian, archived from the original on 5 July 2008, retrieved 2 July 2008

- Bửu, Ý (19 June 2004). "Xứ Huế Người Huế". Tuổi Trẻ. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- "Ao dai – Hue's piquancy". VietnamNet. 18 June 2004. Archived from the original on 4 February 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- Ngoc, Huu; Borton, Lady (2006). Am Thuc Xu Hue: Hue Cuisine. Vietnam.

- "Hue – A Panoramic View of the Ancient Capital – Asia Travel Blog". 30 November 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- rpcpost. "Hue, Vietnam: Try The Food". gonomad.com – GoNOMAD Travel. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- "Thich Nhat Hanh Returns Home". Plum Village. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Vietnam's eight World Heritage Sites. Tuoi Tre News. 22 July 2014.

- Pham, Sherrise; Emmons, Ron; Eveland, Jennifer; Lin-Liu, Jen (2009). Frommer's south-east Asia. Frommer's. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-470-44721-5.

- "Hue; Information & Statistics". Travel-Tourist-Information-Guide.com. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Advancing green growth in the tourism sector: The case of Hue, Vietnam Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Kyoko Kusakabe, Pujan Shrestha, S. Kumar and Khanh Linh Nguyen, the Asian Institute of Technology, Chiang Mai Municipality and the Hue Centre for International Cooperation, 2014

- Advancing green growth in the tourism sector: The case of Hue, Vietnam Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Kyoko Kusakabe, Pujan Shrestha, S. Kumar and Khanh Linh Nguyen, the Climate and Development Knowledge Network, 2014

- "OutLine of Hue Central Hospital". Japan International Cooperation Agency. Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- "شهرهای بندر انزلی و هوء در ویتنام خواهر خوانده شدند". www.aftabir.com (in Persian). aftabir. 19 July 2004. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Hue, Vietnam". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- "Jumelages et coopérations" (in French). Retrieved 20 February 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Huế. |

- Thua Thien Hue Province official website

- 4538731 Huế on OpenStreetMap