Hoklo people

The Hoklo people are Han Chinese people whose traditional ancestral homes are in southern Fujian, China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, and by many overseas Chinese throughout Southeast Asia. They are also speakers of Hokkien, a prestige dialect on the basis of preponderance of their Bamboo network billionaires, in the Southern Min language family, and known by various endonyms (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hok-ló-lâng/Hō-ló-lâng/Ho̍h-ló-lâng/Hô-ló-lâng), or other related terms such as Banlam (Minnan) people (閩南儂; Bân-lâm-lâng) or Hokkien people (福建儂; Hok-kiàn-lâng). "Hokkien" is sometimes erroneously used to refer to all Fujianese people.

閩南儂 | |

|---|---|

_(14597338250).jpg) A Hokkien family in Southern Fujian, 1920. | |

| Total population | |

| ~40,000,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangdong | |

| Majority of Han Taiwanese people (~16,321,075) | |

| Largest group of Indonesian Chinese[2] | |

| Largest group of Chinese Singaporeans | |

| Largest Group of Chinese Filipinos[3] | |

| One of the largest groups of Malaysian Chinese | |

| One of the three largest groups of Burmese Chinese (figured combined with Cantonese)[4] | |

| 70,000+[5] | |

| Minority population | |

| Minority population | |

| Significant group among ethnic Sinoa | |

| Languages | |

| Mother tongue: Quanzhang Minnan (Hokkien) Others: Mandarin, English, national language(s) of respective countries they inhabit | |

| Religion | |

| Chinese folk religions (including Taoism, Confucianism, ancestral worship and others), Mahayana Buddhism and non-religious | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Han Chinese, Hoklo Taiwanese, Hoklo Americans, ancient Minyue† and other Min speakers | |

Etymology

In Taiwan, there are three common ways to write Hoklo in Chinese characters (Hokkien pronunciations are given in Pe̍h-ōe-jī), although none have been established as etymologically correct:[6]

- 福佬; Hok-ló; 'Fujian folk' – mistakenly used by outsiders to emphasize their native connection to Fujian province. It is not an accurate transliteration in terms from Hokkien itself although it may correspond to an actual usage in Hakka.

- 河洛; Hô-lo̍k; 'Yellow River and Luo River' – emphasizes their purported long history originating from the area south of the Yellow River. This term does not exist in Hokkien. The transliteration is a phonologically inaccurate folk etymology, though the Mandarin pronunciation Héluò has gained currency through the propagation of the inaccurate transliteration.[6]

- 鶴佬; Ho̍h-ló; 'crane folk' – emphasizes the modern pronunciation of the characters (without regard to the meaning of the Chinese characters); phonologically accurate.

Meanwhile, Hoklo people self-identify as 河老; Hô-ló; 'river aged'.[7]

In Hakka, Teochew, and Cantonese, Hoklo may be written as Hoglo (學老; 'learned aged') and 學佬 ('learned folk').

Despite the many ways to write Hoklo in Chinese, the term Holo[8][9] (Hō-ló/Hô-ló)[10] is used in Taiwan to refer to the language (Taiwanese Hokkien), and those people who speak it.

Culture

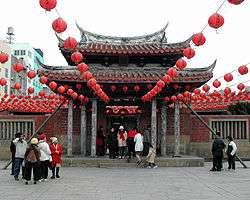

Architecture

Hoklo architecture is, for the most part, similar to any other traditional Chinese architectural styles. Hoklo shrines and temples have tilted sharp eaves just like the architecture of Han Chinese due to superstitious beliefs. However, Hoklo shrines and temples do have special differences from the styles in other regions of China: the top roofs are high and slanted with exaggerated, finely-detailed decorative inlays of wood and porcelain.

The main halls of Hoklo temples are also a little different in that they are usually decorated with two dragons on the rooftop at the furthest left and right corners and with a miniature figure of a pagoda at the center of the rooftop. One such example of this is the Kaiyuan Temple in Fujian, China. Other than these minor differences, Hoklo architecture is basically the same as any other traditional Chinese architecture in any other Han Chinese region.

Language

The Hoklo people speak the mainstream Hokkien (Minnan) dialect which is mutually intelligible to the Teochew dialect but to a small degree. Hokkien can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty, and it also has roots from earlier periods such as the Northern and Southern Dynasties and also a little influence from other dialects as well.

Hokkien has one of the most diverse phoneme inventories among Chinese varieties, with more consonants than Standard Mandarin or Cantonese. Vowels are more-or-less similar to that of Standard Mandarin. Hokkien varieties retain many pronunciations that are no longer found in other Chinese varieties. These include the retention of the /t/ initial, which is now /tʂ/ (Pinyin 'zh') in Mandarin (e.g. 'bamboo' 竹 is tik, but zhú in Mandarin), having disappeared before the 6th century in other Chinese varieties.[11] Hokkien has 5 to 7 tones or 7 to 9 tones according to traditional sense, depending on variety of hokkien spoken such as the Amoy dialect for example has 7-8 tones.

Diaspora

Taiwan

About 70% of the Taiwanese people descend from Hoklo immigrants who arrived to the island prior to the start of Japanese rule in 1895. They could be categorized as originating from Xiamen, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou based on their dialects and districts of origin.[12] People from the former two areas (Quanzhou-speaking) were dominant in the north of the island and along the west coast, whereas people from the latter two areas (Zhangzhou-speaking) were dominant in the south and perhaps the central plains as well.

Southeast Asia

The Hoklo or Hokkien-lang (as they are known in these countries) are the largest dialect group among the Malaysian Chinese, Singapore and southern part of Thailand. They constitute the highest concentrations of Hoklo or Hokkien-lang in the region. The various Hokkien dialects/Minnan are still widely spoken in these countries but the daily use are slowly decreasing in favor of Mandarin Chinese, English or local language.

The Hoklo or Hokkien-lang are also the largest group among the Chinese Indonesians. Most speak only Indonesian.

In the Philippines, the Hoklo or Hokkien-lang form the majority of the Chinese people in the country. The Hokkien dialect/Minnan is still spoken there.

Hailufeng Hokkiens

The Minnan speaking people in Haifeng and Lufeng are known as Hailufeng Hokkiens or Hailufeng Minnan, in a narrow scope, but are often mistaken by outsiders as Chaozhou/Teochew people in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.

Chen Jiongming is a famous Hailufeng Hokkien who served as the governor of the Guangdong and Guangxi provinces during the Republic of China.

United States

After the 1960s, many Hokkiens from Taiwan began immigrating to the United States and Canada.

Notable Hoklo people

References

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2005), "Indonesia", Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15th ed.), Dallas, T.X.: SIL International, ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6, retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Ng, Maria; Holden, Philip, eds. (1 September 2006). Reading Chinese transnationalisms: society, literature, film. Hong Kong University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-962-209-796-4.

- Mya Than (1997). Leo Suryadinata (ed.). Ethnic Chinese As Southeast Asians. ISBN 0-312-17576-0.

- 2005-2009 American Community Survey

- "Language Log » Hoklo". languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu.

- Gu Yanwu (1985). 《天下郡國利病書》:郭造卿《防閩山寇議》. 上海書店. OCLC 19398998.

漳猺人與虔汀潮循接壤處....常稱城邑人為河老,謂自河南遷來畏之,繇陳元光將卒始也

- Exec. Yuan (2014), pp. 36,48.

- Exec. Yuan (2015), p. 10.

- Governor-General of Taiwan (1931–1932). "hô-ló (福佬)". In Ogawa Naoyoshi (ed.). 臺日大辭典 [Taiwanese-Japanese Dictionary]. (in Japanese and Hokkien). 2. Taihoku: 同府 [Dōfu]. p. 829. OCLC 25747241..

- Kane, Daniel (2006). The Chinese language: its history and current usage. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 100–102. ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5.

- Davidson (1903), p. 591.

Bibliography

- Brown, Melissa J (2004). Is Taiwan Chinese? : The Impact of Culture, Power and Migration on Changing Identities. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23182-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1887893. OL 6931635M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Republic of China Yearbook 2014 (PDF). Executive Yuan, R.O.C. 2014. ISBN 9789860423020. Retrieved 2016-06-11.

- The Republic of China Yearbook 2015. Executive Yuan, R.O.C. 2015. ISBN 9789860460131. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-06-06.