Fuzhou Tanka

Fuzhou Tanka (Fuzhou dialect: 曲蹄; Foochow Romanized: Kuóh-dà̤; Simplified Chinese: 福州疍民 Hók-ciŭ Dáng-mìng; 江妹仔 Gĕ̤ng-muói-giāng; 曲蹄婆 Kuóh-dà̤-bò̤), or Fuzhou Boat People, is an ethnic group in Fujian, China. A branch of the Tanka people, they traditionally lived on sampans in the lower course of Min River and the coast of Fuzhou in Fujian Province most of their lives and have been officially recognized as Han Chinese since 1955.[1]

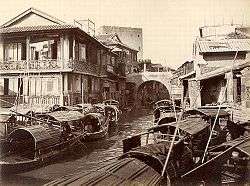

Fuzhou Tanka people on their boats in Min River, Fuzhou, Fujian, China, 1910. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| The lower course of Min River and the coast of Fuzhou, Fujian Province in China | |

| Languages | |

| Fuzhounese and Standard Mandarin (second language) | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic and Taoism |

Origin and etymology

There are several different views on the origin of Fuzhou Tanka. The mainstream theory believes that Fuzhou Tanka are descendants of the Baiyue of ancient times.[1] As a branch of the Tanka people, Fuzhou Tanka has been in South China for more than 2000 years.[2] Their Fuzhounese name "Kuóh-dà̤" (曲 蹄) is a derogatory term used by the Fuzhou people on land, which can be literally translated into "bowlegged" and might come from the bow shape of their legs caused by longtime living in the low cabins of their boats.[3][4]

The Amoy University anthropologist Ling Hui-hsiang wrote on his theory of the Fujian Tanka being descendants of the Baiyue. He claimed that Guangdong and Fujian Tanka are definitely descended from the old Pai Yue peoples, and that they may have been ancestors of the Malay race.[5]

Language

Fuzhou Tanka now speak the Fuzhou dialect, which is widely used by the majority Fuzhou people in this region. Mandarin has also been brought to many of them through national compulsory education. However, they had their own language in history, but gradually abandoned it. In Ming Dynasty, many of them were already able to speak the Fuzhou dialect or other Eastern Min languages.[6]

Society

Traditionally, Fuzhou Tanka people lived on boats in most of their lives. They were severely discriminated by land living Fuzhounese residents. Their life depended on fishing and ferrying, and most of them remained poor and uneducated before the founding of Republic of China. Fuzhou Tanka people had a rich tradition of folk music, especially call and response. They also had different views on chastity and remarriage from the land living Han Chinese. Pre-marital sex and remarriage were not restricted in their society. Due to the discriminatory policy imposed by the land living Han majority, Fuzhou Tanka were forced to dress themselves in a humble way to show their inferiority to the land residents.[4]

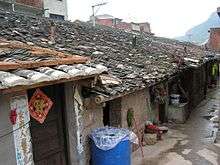

By the second half of the 19th century, many Tanka people had already been converted to Roman Catholicism. Some of these Catholic Tanka consequently moved onto land under the protection of the Catholic Church. In the Republic of China era, the ethnic egalitarianism was guaranteed by law. Since the 1950s, the Communist government began to resettle Fuzhou Tanka to land dwellings. As a result, many Fuzhou Tanka villages were built along the Min River and the coast. Nowadays, most Fuzhou Tanka people have abandoned their traditional waterborne lives and intermarriage is common. Their traditions, such as Fuzhou Tanka folk music, are under threat as well.[1][7][8]

Discrimination against Fuzhou Tanka

Before the founding of Republic of China, the Fuzhou Tanka were generally treated by land Chinese residents as mean and inferior. They were not allowed to dwell on land, receive education, wear silk clothes or work in government or army. In some areas, they were even forbidden to walk on land, otherwise, they would be faced with death threats. Since the 18th century several attempts had been made by the Qing and Kuomintang governments to lift the discrimination against Tanka people, but it was only in the People's Republic of China era that all the discriminatory policies were completely eliminated.[4][7] Before the founding of the People's Republic of China, the 'gypsies of the sea' were not allowed to go ashore or marry the people living along the beach.[9]

Religion

Before the 19th century, many Fuzhou Tanka practiced Taoism, worshiping Mazu, Linshui and other gods and goddesses. In the late 19th century, many Fuzhou Tanka people were converted to Roman Catholicism. Received, protected and assisted by the Roman Catholic Church in Fuzhou through Protectorate of missions, some of them were able to build simple land dwellings. Currently, the majority of Fuzhou Tanka people are Roman Catholic, which constitute a significant portion in Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Fuzhou.[10]

Surnames

The Fuzhou Tanka have different surnames than the Tanka of Guangdong.[11] Qing records indicate that "Weng, Ou, Chi, Pu, Jiang, and Hai" (翁, 歐, 池, 浦, 江) were surnames of the Fuzhou Tanka.[12] Qing records also stated that Tanka surnames in Guangdong consisted of "Mai, Pu, Wu, Su, and He", alternatively some people claimed Gu and Zeng as Tanka surnames.[13]

See also

- Tanka (ethnic group)

References and notes

- Jian-min Li (李健民), Origin and Migration of Mindong's Fishermen (闽东疍民的由来及历史变迁) Archived 2010-01-29 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Ningde Teachers' College, 2009 Vol. 2, pp.38–44 (in Chinese)

- 刘传标,闽江流域疍民的文化习俗形态 (in Chinese)

- Local Annals of Min County (闽县乡土志) (in Chinese)

- 吴高梓:福州疍民调查[J],社会学界(第四卷),1930 (in Chinese)

- Murray A. Rubinstein (2007). Murray A. Rubinstein (ed.). Taiwan: a new history (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 34. ISBN 0-7656-1494-4.

"which modern people are the Pai Yueh"..,...So is it possible that there is a relationship between the Pai Yueh and the Malay race?...Today in riverine estuaries of Fukien and Kwangtung are another Yueh people, the Tanka ("boatpeople"). Might some of them have left the Yueh tribes and set out on the seas? (1936: 117)

- 郭志超, 《闽台民族史辨》, 黄山书社, 2006年 (in Chinese)

- County Annals of Luoyuan (罗源县志),Fangzhi Publishing House,1998.11,ISBN 7-80122-390-X (in Chinese)

- The Endangered Fuzhou Tanka Folk Music (濒临失传的“福州疍民渔歌”) Archived 2009-12-01 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- "China's Tanka boat people floating homes".

- Fan Zhengyi, Researching into the Belief of Boatmen in Fujian in Modern Time, Journal of Putian University, 2005 12(6) (in Chinese)

- Anders Hansson (1996). Chinese outcasts: discrimination and emancipation in late imperial China. Volume 37 of Sinica Leidensia. BRILL. p. 117. ISBN 90-04-10596-4.

Unless a change of surnames occurred for some unknown reason, or unless the ' water names' are not the real names of the Fujian boat people, it would seem that the Dan people lacked Chinese-style surnames at the time the Fujian branch

- Anders Hansson (1996). Chinese outcasts: discrimination and emancipation in late imperial China. Volume 37 of Sinica Leidensia. BRILL. p. 116. ISBN 90-04-10596-4.

In a late Qing dynasty work which has a section on boat people that mainly refers to those in Fujian, common surnames are said to be Weng 翁 ('old fisherman'), Ou 歐, Chi 池 (pond), Pu 浦 (river bank), Jiang 江 (river) and Hai 海 (sea). None of those surnames is a very common one in China and a few are very rare.

- Anders Hansson (1996). Chinese outcasts: discrimination and emancipation in late imperial China. Volume 37 of Sinica Leidensia. BRILL. p. 116. ISBN 90-04-10596-4.

Some of them list the five names Mai 麥, Pu 濮, Wu 吴, Su 蘇 and He 何 The Huizhou prefectural gazetteer even states that there are no other boat people surnames, while others also add Gu 顧 and Zeng 曾 to make seven

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fuzhou Tanka. |