History of Seville

Seville has been one of the most important cities in the Iberian Peninsula since ancient times; the first settlers of the site have been identified with the Tartessian culture. The destruction of their settlement is attributed to the Carthaginians, giving way to the emergence of the Roman city of Hispalis, built very near the Roman colony of Itálica (now Santiponce), which was only 9 km northwest of present-day Seville. Itálica, the birthplace of the Roman emperors Trajan and Hadrian, was founded in 206-205 BC. Itálica is well preserved and gives an impression of how Hispalis may have looked in the later Roman period. Its ruins are now an important tourist attraction. Under the rule of the Visigothic Kingdom, Hispalis housed the royal court on some occasions.

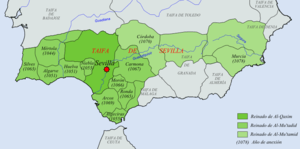

In al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) the city was first the seat of a kūra (Spanish: cora),[1] or territory, of the Caliphate of Córdoba, then made capital of the Taifa of Seville (Arabic: طائفة أشبيليّة, Ta'ifa Ishbiliya), which was incorporated into the Christian Kingdom of Castile under Ferdinand III, who was first to be interred in the cathedral. After the Reconquista, Seville was resettled by the Castilian aristocracy; as capital of the kingdom it was one of the Spanish cities with a vote in the Castilian Cortes, and on numerous occasions served as the seat of the itinerant court. The Late Middle Ages found the city, its port, and its colony of active Genoese merchants in a peripheral but nonetheless important position in European international trade, while its economy suffered severe demographic and social shocks such as the Black Death of 1348 and the anti-Jewish revolt of 1391.

After the discovery of the Americas, Seville became the economic centre of the Spanish Empire as its port monopolised the trans-oceanic trade and the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) wielded its power, opening a Golden Age of arts and letters. Coinciding with the Baroque period of European history, the 17th century in Seville represented the most brilliant flowering of the city's culture; then began a gradual economic and demographic decline as navigation of the Guadalquivir River became increasingly difficult until finally the trade monopoly and its institutions were transferred to Cádiz.

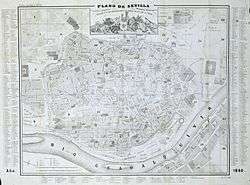

The city was revitalised in the 19th century with rapid industrialisation and the building of rail connections, and as in the rest of Europe, the artistic, literary, and intellectual Romantic movement found its expression here in reaction to the Industrial Revolution. The 20th century in Seville saw the horrors of the Spanish Civil War, decisive cultural milestones such as the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 and Expo'92, and the city's election as the capital of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia.

Prehistory and antiquity

_002.jpg)

The original core of the city, in the neighbourhood of the present-day street, Cuesta del Rosario, dates to the 8th century BC,[2] when Seville was on an island in the Guadalquivir.[3] Archaeological excavations in 1999 found anthropic remains under the north wall of the Real Alcázar dating to the 8th–7th century BC.[4]

The town was called Spal or Ispal by the Tartessians, the indigenous pre-Roman Iberian people of Tartessos (the name given to their kingdom by the Greeks); they controlled the Guadalquivir Valley and were important trading partners of the neighbouring Phoenician trading colonies on the coast, which later passed to the Carthaginians.[5] The Tartessian culture was succeeded by that of the Turdetani (so-called by the Romans) and the Turduli.

Ispal advanced in its civilisation and was culturally enriched by its frequent contact with the peaceful Phoenician traders.[6] Commercial colonisation activity in the region changed dramatically in the 6th century BC when the Carthaginians achieved dominance of the western Mediterranean after the fall of the Phoenician city-states of Canaan to the Persian empire. This new phase of colonisation involved the expansion of Punic territory through military conquest; later Greek sources impute the destruction of Tartessos to Carthaginian military assaults on the Seville of the Cuesta del Rosario, assuming it to be Tartessian at the time. Carthaginians had caused the collapse of Tartessos by 530 BC, either by armed conflict or by cutting off Greek trade in support of the Phoenician colony of Gades (present-day Cádiz).[7] Carthage also besieged and took over Gades at this time.

Roman Hispalis

During the Second Punic War, Roman troops under the command of the general Scipio Africanus achieved a decisive victory in 206 BC over the full Carthaginian levy at Ilipa (now the city of Alcalá del Río),[8] near Ispal, which resulted in the evacuation of Hispania by the Punic commanders and their successors in the southern peninsula. Before returning to Rome, Scipio settled a contingent of veteran soldiers on a hill close to Hispalis, but far enough away to deter belligerents, and thus founded Italica, the first provincial city in which the inhabitants had all the rights of Roman citizenship. The two cities had different characters: Híspalis was a Hispano-Roman town of craftsmen and a regional financial and commercial hub; while Italica, the birthplace of the Roman emperors Trajan and Hadrian,[9] was residential and fully Roman. Hispalis developed into one of the great market and industrial centres of Hispania, and Italica remained a typically Roman residential city.

During this period Hispalis was the district capital of the Hispalense, one of the four legal convents (Conventi iuridici, judicial assemblies the governors summoned with some frequency in the major cities) of the imperial province of Baetica.

The Romans Latinised the Iberian name of the city, 'Ispal', and called it Hispalis. Although the city was rebuilt after being pillaged by the Carthaginians, the name 'Hispalis' appeared for the first time in the Augustan History in 49 BC, five years before Julius Caesar granted it the status of Roman colony to celebrate his victory over Pompey in 54 BC. Isidore says in his Etymologies, XV 1, 71:[10]

Hispalim Caesar Iulius condidit, quae ex suo et Romae urbis vocabulo Iuliam Romulam nuncupavit. Hispalim autem a situ cognominata est, eo quod in solo palustri suffixis in profundo palis locata sit, ne lubrico atque instabili fundamento cederet.

In English:

Hispalis was founded by Julius Caesar, who named the city 'Julia Romula' after himself and the city of Rome. However, the cognomen 'Híspalis' is due to its situation, as it is built on pilings above marshy ground, so as not to yield to a sliding and unstable foundation.

Although this etymology is not accurate, it is likely that the city was considered untenable as a residence by the Romans for its instability, being built on alluvial soil and frequently threatened by flooding of the Guadalquivir River. Isidore's reference to the foundation pilings of Hispalis was confirmed when their remains were discovered by archaeological excavations in Calle Sierpes, where, according to the historian Antonio Collantes de Teran, "piles were sharpened on their lower ends, regularly driven into the sandy subsoil, and obviously served to consolidate the foundation in that place." Similar findings have been made at the Plaza de San Francisco. Salvador Ordóñez Agulla, however, asserts that these pilings are the remains of ship piers of the river (called the Baetis in Roman times) port.[11]

In 45 BC, after the Roman Civil War ended at the Battle of Munda, Híspalis built city walls and a forum, completed in 49 BC, as it grew into one of the preeminent cities of Hispania; the Latin poet Ausonius ranked it tenth among the most important cities of the Roman Empire. Hispalis was a city of great mercantile activity and an important commercial port. The area around the present Plaza de la Alfalfa was the intersection of the two main axes of the city, the Cardo Maximus which ran north to south, and the Decumanus Maximus which ran east to west. In this area was the Roman forum, which included temples, baths, markets and public buildings; the Curia and the Basilica may have been near the present-day Plaza del Salvador.[12]

What was formerly the eastern part of the Decumanus Maximus is modern-day Calle Aguilas, while the northern section of the Cardus Maximus coincides with Calle Alhondiga. This leads to the conclusion that what is today La Plaza del Alfalfa, at the junction of these two streets, may have been the location of the Imperial Forum,[13] while the nearby Plaza del Salvador was probably the site of the Curia and Basilica.

In the mid-second century the Moors (Mauri in ancient Latin) twice attempted invasions,[14] and were finally driven back by Roman archers.

Tradition says Christianity came early to the city; in the year 287, two potter girls, the sisters Justa and Rufina, now patron saints of the city, were martyred, according to legend, for an incident that arose when they refused to sell their wares for use in a pagan festival. In anger, locals broke all of their dishes and pots, and Justa and Rufina retaliated by smashing an image of the goddess Venus or of Salambo. They were both imprisoned, tortured and killed by the Roman authorities.[15]

Middle Ages

Visigothic rule

In the 5th century Hispalis was taken by a succession of Germanic invaders: the Vandals led by Gunderic in 426, the Suebi King Rechila in 441, and finally the Visigoths, who would control the city until the 8th century, their supremacy challenged for a time by the Byzantine presence on the Mediterranean coast. After the defeat of the Franks in 507, the Visigothic Kingdom abandoned its former capital in Toulouse, north of the Pyrenees, and was gaining ground on the various peoples scattered throughout the Hispanic territory by moving the royal residence to different cities until it was fixed in Toledo. Seville was chosen during the reigns of Amalaric, Theudis and Theudigisel. This last king was assassinated at a banquet for the nobles of Hispalis in an episode known as the 'Supper of Candles' in 549.[16] The cause is debated and may be a reflection of the division between the Hispanic communities and the Visigoths (Baetica was more susceptible to outbreaks of dissension than the center of the Iberian peninsula), or even a conspiracy of Visigothic nobles.

Under Visigothic rule, Híspalis was known as Spali.[17] After the short reign of Theudigisel, the successor of Theudis, Agila I was elected king in 549. The Visigoths were engaged in internal power struggles when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I took the opportunity to try to conquer Baetica. After many battles and the defeat of several of their leaders, the Visigoths eventually managed to conquer every corner of the region. In 572, Leuvigild, the designee to reign, obtained the kingdom after the death of his brother Liuva I. In 585, his son Hermenegild, after converting to Catholicism (in contradistinction to the Arianism of former kings) rebelled against his father and proclaimed himself king in the city. Legend tells that in order to force his way, Leuvigild changed the course of the Guadalquivir River, hindering the passage of the inhabitants and causing a drought.[18] The old channel passed by the present-day Alameda de Hercules. In 586, Leuvigild's other son Reccared I acceded to the throne and with Spali itself went on to enjoy a time of great prosperity. After the Muslim invasion of Spain, the city became, next to Cordoba, one of the most important in Western Europe.

Christianity

In Visigothic times two Catholic prelates of Hispalis, Leander and Isidore, are notable; they were brothers and both were canonised as saints. Leander, in addition to his intensive labors in reforming the regular and the secular clergy, converted Hermenegild, viceroy of Baetica and son of King Leuvigild (an Arian adherent), to Catholicism. The Visiothic prince rebelled against his father and began an uprising supported by the Hispano-Roman nobility, upon the failure of which Hermenegild was executed in 585. After the death of Leuvigild in 586, Leander had a prominent role in the Third Council of Toledo in 589, where the new king Reccared I, Hermenegild's brother, converted to Catholicism along with all the Visigothic nobility. Isidore wrote a set of twenty encyclopaedic books known as the Etymologies that contained all the knowledge of the ancient Greco-Roman culture (medicine, music, astronomy, theology, etc.), which was of great influence throughout medieval Europe.[19]

Muslim al-Andalus

The Muslim general Musa bin Nusayr commanded Tariq ibn Ziyad to invade Spain in the late spring of 711 with an army of 9,000 men. That summer, these forces fought a large army raised by the Visigothic king Roderic, who was killed at the Battle of Guadalete. When Tariq met little resistance as his divisions moved through the Visigothic kingdom, it is said that Musa was jealous that such a victory should be won by a Berber freedman. Accompanied by his son Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa, Musa landed in Spain in 712 with his own army of 18,000 veteran Arabs and proceeded to the further conquest of Visigothic territory.[20] They took Medina-Sidonia and Carmona; then Prince Abd al-Aziz took Hispalis in 712 after a long siege.[21] Until his assassination at the hands of his cousins in 716, the city served as the capital of al-Andalus, the name given the Iberian Peninsula as a province of the Islamic empire of the Umayyad Caliphate.

Following the siege and conquest of the city, its Roman name, Hispalis, was changed to the Arabic Išbīliya (إشبيلية) or Ishbiliya.[22] During this period of Muslim rule a richly complex culture developed. The emirate favored the expansion of Islam through concessions to those Christians who converted to Islam, called Muwallads, privileges not enjoyed by those who remained Christian, known as (Mozarabs). The city was called by the name Ixbilia in the Mozarabic language, which became Sivilia, and finally reached the form "Sevilla", as it is known today.[23]

The Umayyad dynasty was established in al-Andalus when Abd al-Rahman I took Išbīliya without violence in March 756,[24] then won Córdoba in the Battle of Musarah where he defeated Yusuf al-Fihri, the governor of al-Andalus,[25] who had ruled independently since the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750. After his victory Abd al-Rahman I proclaimed himself the Emir of al-Andalus,[26] which later became part of the Caliphate of Córdoba when Abd ar-Rahman III proclaimed himself Caliph in 929,[27] and Išbīliya was made the capital of a kūra (territory).[28] Abd al-Rahman I appointed his Umayyad kinsman Abd al-Malik ibn Umar ibn Marwan governor of Seville. By 774 Abd al-Malik definitively crushed opposition to the Umayyads by the Arab garrisons and local elites of Seville and its territory. His family settled in the town and became a major component of the government in Cordoba, serving as viziers and generals of the successive emirs and caliphs, and some of his descendants attempted to wrest the caliphate from the descendants of Abd al-Rahman I.[29][30][31]

The Ad-Abbas Mosque was built in 830,[32] it currently holds the Church of El Salvador.

On 1 October 844, when most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by the Emirate of Córdoba, a flotilla of about 80 Viking ships, after attacking Asturias, Galicia and Lisbon, ascended the Guadalquivir to Išbīliya, and besieged it for seven days, inflicting many casualties and taking numerous hostages with the intent to ransom them. Another group of Vikings had gone to Cádiz to plunder while those in Išbīliya waited on Qubtil (Isla Menor), an island in the river, for the ransom money to arrive.[33] Meantime, the emir of Cordoba, Abd ar-Rahman II, prepared a military contingent to meet them, and on November 11 a pitched battle ensued on the grounds of Talayata (Tablada).[34] The Vikings held their ground, but the results were catastrophic for the invaders, who suffered a thousand casualties; four hundred were captured and executed, some thirty ships were destroyed.[35] It was not a total victory for the emir's forces, but the Viking survivors had to negotiate a peace to leave the area, surrendering their plunder and the hostages they had taken to sell as slaves, in exchange for food and clothing. The Vikings made several incursions in the years 859, 966 and 971, but with intentions more diplomatic than bellicose, although an attempt at invasion in 971 was frustrated when the Viking fleet was totally annihilated.[36] Vikings attacked Tablada again in 889 at the instigation of Kurayb ibn Khaldun of Seville. Over time, the few Norse survivors converted to Islam and settled as farmers in the area of Coria del Río, Carmona and Moron, where they engaged in animal husbandry and made dairy products (reputedly the origin of Sevillian cheese).[37]

The city grew rich during the years when it was a dependent of the Emirate and later of the Caliphate of Córdoba. After the fall of the caliphate Ishbilya became independent and was capital of one of the more powerful Taifas from 1023 until 1091, under the rule of the Abbadi, a Muslim dynasty of Arabic origin. However, Christians often made threatening advances into the Taifa, and in 1063, a Christian incursion under the command of Ferdinand I of Castile discovered how weak the military force was that occupied these realms. Putting up little resistance, in a few years the king of Išbīliya, Al-Mutamid, had to buy peace and pay an annual tribute, making Išbīliya for the first time a tributary of Castile.[38]

The Alcázar of Seville (Reales Alcázares de Sevilla or Royal Alcázars of Seville) is a royal palace originally built as a Moorish fort. No other Muslim building in Spain has been so well preserved.[39] Inhabited for a time by the Abbatid, Almoravid, and Almohad kings, its embattled enclosure became the dwelling of Ferdinand I, and was rebuilt by Peter of Castile (1353–64), who employed Granadans and Muslim subjects of his own (mudejares) as its architects. Its principal entrance, with Arab façade, is in the Plaza de la Monteria, once occupied by the dwellings of the hunters (monteros) of Espinosa. The principal features of the Alcázar are: the Patio de las doncellas (Court of the Ladies), restored by Charles I, with its fifty-two uniform columns of white marble supporting interlaced arches and its gallery of precious arabesques;[40] as well as the Hall of Ambassadors, which, with its cupola, dominates the rest of the building—its walls are covered with fine azulejos (glazed tiles) and Arab decorations.[41]

From the late 11th century to the mid-12th century the Taifa kingdoms were united under the Almoravids (of Saharan origin), and after the collapse of the Almoravid empire, in 1149 the town was taken by the Almohads (of North African origin).[42] These were boom times economically and culturally for Ishbilya; great architectural works were built, among them: the minaret, called Giralda (1184–1198), of the great mosque; the Almohad palace, Al-Muwarak, on the present site of the Alcázar;[43] and the pontoon-bridge connecting Triana on the opposite bank of the Guadalquivir to Seville.[44]

The Torre del Oro (Tower of Gold) is a 12-sided military watchtower built during the time of the Almohad dynasty. The tower, situated near the bank of the Guadalquivir, was built around 1200 by order of the Muslim Governor Abu Elda,[45] who ordered a great iron chain to be drawn across the river, with two military watchtowers built on opposite sides. These served as anchor points to control access to Seville via the waterway.[46] The surviving tower was given the name "Torre del Oro", supposedly because it was decorated with golden azulejo tiles.[47] During the Muslim rule it was used as a prison and as a shelter during floods, among other purposes.[48]

Castillian conquest

In 1247, the Christian King Ferdinand III of Castile and Leon began the conquest of Andalusia. After conquering Jaén and Córdoba, he seized the villages surrounding the city, Carmona Lora del Rio and Alcalá del Rio, and kept a standing army in the vicinity, the siege lasting for fifteen months. The long siege had caused havoc in the local population.[49] The decisive action took place in May 1248 when Ramon Bonifaz sailed up the Guadalquivir and severed the Triana bridge that made the provisioning of the city from the farms of the Aljarafe possible.[50] The city surrendered on 23 November 1248.[51]

The Catholic religion was confined to the parish Church of Saint Ildefonso until the restoration following the reconquest of the city by Ferdinand. At that time the Bishop of Cordova, Gutierre de Olea, purified the great mosque and prepared it for celebration of the mass on 22 December. The king deposited in the new Seville Cathedral two famous images of the Blessed Virgin: "Our Lady of the Kings", an ivory statue which Ferdinand always carried with him in battle; and the silver image, "Our Lady of the See".[52]

The royal residence and the court were itinerant, so there was no permanent capital. Burgos and Toledo disputed the priority;[53] thereafter the court most often resided in Seville,[54] the king's favorite city. On 30 May 1252, King Ferdinand III died in the Alcázar; he was buried in the cathedral, formerly the great mosque, under an epitaph written in Latin, Castilian, Arabic and Hebrew,[55] a fitting tribute to his sobriquet of "King of the three religions".[56] Ferdinand was canonised in 1671; his feastday on 30 May is a local holiday in Seville, he being its patron saint.

During the reign of Ferdinand's son, Alfonso X the Wise, Seville remained one of the capitals of the kingdom, as the seat of government now rotated between Toledo, Murcia and Seville. Alfonso ordered the construction of the Gothic Palace of the Alcázar and built the Church of Santa Ana (Iglesia de Santa Ana) in the Triana neighbourhood,[57] the first Catholic church built in Seville after Muslim rule ended in the city; its architecture combines the early Gothic and the Mudéjar styles.[58]

A great patron of learning, in 1254 Alfonso X founded the Estudio General o Universidad de Sevilla for instruction in Latin and Arabic; it did not continue, however—the present University of Seville is considered to have been founded in 1505. The spirit of the king's desire to gather all knowledge, organise it, and disseminate it with missionary zeal is clearly reflected in the Siete Partidas (Seven-Part Code), one of the great foundational works of the Middle Ages. This is a judicial code based on Roman law and composed by a group of legal scholars chosen by Alfonso himself. It may be said that the king was architect and editor of this compendious and magisterial work of cooperative scholarship, known originally as the "Book of Laws"; this and other works he patronised established Castilian as a language of higher learning in Europe.[59]

Before his death, Ferdinand III had long planned the invasion of North Africa, and at the beginning of his own reign, Alfonso X appealed to Pope Alexander IV to endorse such an incursion as a religious crusade, and even built shipyards at Seville for that purpose. In 1260, he appointed a sea governor (adelantado de la mar), and the port of Salé, (Arabic:Salâ), on the Atlantic coast of Morocco was occupied briefly. Encouraged by the apparent success of that raid, Alfonso summoned the Cortes to Seville in January 1261 to seek counsel, but no further action was taken. The king may have decided that before undertaking any other ventures in Africa, it would be prudent to gain control of all ports of access to the Iberian peninsula. Years later, the king again summoned the Cortes to Seville in the fall of 1282; to raise monies for waging his war against the Moors, he proposed a debasement of the coinage, to which the assembly reluctantly consented.[60]

"NO8DO", which appears on the city's coat of arms, is the official motto and the subject of one of the many legends of Seville. The motto is an heraldic pun in Spanish, i.e., a rebus combining the Spanish syllables (NO and DO) and a drawing in between of the figure "8". The figure represents a skein of yarn, or in Spanish, a madeja. When read aloud, "No madeja do" sounds like "No me ha dejado", which means "It [Seville] has not abandoned me".[61] The story of how NO8DO came to be the motto of the city has undoubtedly been embellished throughout the centuries, but history tells that after the conquest of Seville from the Muslims in 1248, King Ferdinand III moved his court to the former Muslim palace, the Alcázar of Seville.

After Ferdinand's death in the Real Alcázar, his son, Alfonso X the Wise, assumed the throne. Alfonso was an intellectual, and a great patron of the sciences and the arts, hence his title. He distinguished himself as poet, astronomer, musician, linguist and legislator. Alfonso's son, Sancho IV of Castile, tried to usurp the throne from his father, but the people of Seville remained loyal to their scholar king. The symbol 'NO8DO' is believed to have originated when, according to legend, Alfonso X rewarded the fidelity of the Sevillanos with the words that now appear on the official coat of arms and the flag of the city of Seville.

The Battle of Salado in 1340 resulted in the opening of maritime trade between southern and northern Europe through the Strait of Gibraltar and a growing presence of Italian and Flemish merchants in Seville, who were key to the inclusion of the southern routes of the Crown of Castile in that commerce. The Black Death of 1348, the great earthquake of 1356 (which caused some casualties and serious damage to many buildings, including the great mosque),[62] and the demographic and economic consequences of the crisis of the fourteenth century were devastating to the city. This aggravation of pre-existing social conflicts found an outlet in the anti-Judaism revolt of 1391, inspired by the anti-Semitic sermons of Ferran Martine, the Archdeacon of Ecija. The Jewish quarter of Seville, one of the largest Jewish communities of the Iberian peninsula, virtually disappeared because of murders and forced mass conversions.[63] Thereafter the converso community of new Christian converts inherited the condition of scapegoat endured by their forebears.

During a stay of the Catholic Monarchs in Seville (1477), Alonso de Ojeda, the Prior of the Dominicans of Seville and a loyal advisor to Queen Isabella, urged action against the conversos and the founding of the Spanish Inquisition.[64][65] The Queen agreed and the Holy Office of the Inquisition was established in 1478. The city was chosen for the first auto de fe, after which six people were burned alive on 6 February 1481.[66]

Early Modern Era

Seville's Golden age in the 16th century

The European discovery of the New World in 1492 was an event of supreme importance for the city which would become the European port of departure to the Americas and the commercial capital of the Spanish Empire.[67] Seville was in the late 15th century one of Castile's major ports, already a cosmopolitan and international commercial centre, trading mainly with England, Flanders and Genoa. The Muslim minority suffered a blow in 1502 when it was forced to convert to Christianity (the Moriscos), to achieve religious conformity in the name of national unity.

The influence and prestige of Seville expanded greatly during the 16th century following the Spanish arrival in America, the commerce of the port driving the prosperity which led to the period of its greatest splendour. The Puerto de Indias in Seville became the principal port linking Spain to Latin America in 1503 with the monopoly created by the royal decree of Queen Isabella I of Castile; this granted the city exclusive privileges as the port of entry and exit for all the Indies trade.[68] To administer this commercial activity, the Catholic Monarchs founded the Casa de Contratación, or House of Trade,[69] (though it was not then located in a specific building, its documents can now be seen in the Archive of the Indies). From here all voyages of exploration and trade had to be approved, thus giving Seville control of the wealth transported from the New World, enforced by laws regarding the contracting of voyages and which routes the ships must follow. Together the Casa de Contratación and the Consulado de mercaderes (the merchant guild founded in 1543) regulated all mercantile, scientific and judicial intercourse with the New World.[70] Consequently, the city grew to over 100,000 inhabitants, making it the largest and most urbanised city in Spain at the time; more of its streets were bricked or paved than in any other in the peninsula.

All goods imported from the New World had to pass through the Casa de Contratación before being distributed throughout the rest of Spain. A 'golden age' of development commenced in Seville, due to its being the only port awarded the royal monopoly for trade with the growing Spanish colonies in the Americas, and the influx of riches from them. Since only sailing ships leaving from and returning to the inland port of Seville could engage in trade with the Spanish Americas, merchants from Europe and other trade centers needed to go to Seville to acquire trade goods from the New World.

A twenty percent tax, the quinto real, was levied by the Casa on all precious metals entering Spain.[71] Trade with the overseas possessions was handled by the merchants' guild based in Seville, the Consulado de Mercaderes, which worked in conjunction with the Casa de Contratación. Since it controlled most of the trade in the Spanish colonies, the Consulado was able to maintain its own monopoly and keep prices high in all the colonies, and even had a part in royal politics. The Consulado thus effectively manipulated the government and the citizenry of both Spain and the colonies, and grew very rich and powerful.[72]

In turn Seville became a metropolis with consulates of all the European governments, and was the home of merchants from all across the continent who settled there to represent their companies. The factories established in the barrio of Triana were famous for their wares, including soap, silk for export to Europe, and ceramics. The city developed into a multicultural centre that nurtured the flowering of the arts, especially architecture, painting, sculpture and literature, thus playing an important role in the cultural achievements of the Spanish Golden Age (El Siglo de Oro). The advent of the printing press in Spain led to the development of a sophisticated Sevillian literary salon.

In the middle of the 13th century, the Dominicans, in order to prepare missionaries for work among the Moors and Jews, had organized schools for the teaching of Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek. To cooperate in this work and to enhance the prestige of Seville, Alfonso the Wise in 1254 established in the city 'general schools' (escuelas generales) of Arabic and Latin. Pope Alexander IV, by the Bull of 21 June 1260, recognised this foundation as a generale litterarum studium. Rodrigo de Santaello, archdeacon of the cathedral and commonly known as Maese Rodrigo, began the construction of a building for a university in 1472. The Catholic Monarchs published the royal decree creating the university in 1502, and in 1505 Pope Julius II granted the Bull of authorization—this is considered the official founding of the present University of Seville. In 1509 the college of Maese Rodrigo was finally installed in its own building, under the name of Santa María de Jesús,[73] but its courses were not opened until 1516. The Catholic Monarchs and the pope granted the power to confer degrees in logic, philosophy, theology, and canon and civil law. The college was situated near the modern Puerta de Jerez. Only two architectural elements remain: the Late Gothic portal which since 1920 has formed part of the entrance to the Convent of Santa Clara, and the small Mudéjar chapel.

At the same time that the royal university was established, there was developed the Universidad de Mareantes (University of Sea-farers), in which body the Catholic Monarchs, by a royal decree of 1503, established the Casa de Contratación with classes for pilots and of seamen, and courses in cosmography, mathematics, military tactics, and artillery. This establishment was of incalculable importance, for it was there that the expeditions to the Indies were organised, and there that the great Spanish sailors were educated.

The Casa had a large number of cartographers and navigators, archivists, record keepers, administrators and others involved in producing and managing the Padrón Real, the secret official Spanish master map used as a template for the maps present on all Spanish ships during the 16th century. It was probably a large-scale chart that hung on the wall of the old Alcázar in Seville.[74]

The numerous official cartographers and pilots included Amerigo Vespucci, Sebastian Cabot, Alonzo de Santa Cruz, and Juan Lopez de Velasco. In 1508 a special position was created for Vespucci, the 'pilot major' (chief of navigation), to train new pilots for ocean voyages. Vespucci, who made at least two voyages to the New World, worked at the Casa de Contratación until his death in 1512.

Important buildings of the Sevillian Golden Age

With its monopoly on the West Indies trade, Seville saw a great influx of wealth. This wealth drew Italian artists such as Pietro Torrigiano, a classmate rival of Michelangelo in the garden of the Medici. Torrigiano executed magnificent sculptures at the monastery of Saint Jerome and elsewhere in Seville, as well as notable tombs and other works which brought the influence of the Italian Renaissance and of humanism to Seville. French and Flemish sculptors such as Roque Balduque arrived also, bringing with them a tradition of a greater realism.

Important historic buildings from this period include the Seville Cathedral, completed in 1506; after Seville was taken by the Christians (1248) in the Reconquista, the city's mosque had been converted to a church. This structure was badly damaged in a 1356 earthquake, and by 1401 the city began building the current cathedral, one of the largest churches in the world and an outstanding example of the Gothic and Baroque architectural styles. The former minaret of the mosque, called the Giralda, survived the earthquake, but the copper spheres that originally topped it fell during the 1365 earthquake, and were replaced with a cross and bell. The new cathedral incorporated the minaret as a bell tower, which was eventually built higher during the Renaissance. It is surmounted by a statue, known locally as "El Giraldillo", representing Faith (1560–1568).

The Archivo General de Indias (General Archive of the Indies), housed in the ancient merchants' exchange, the Casa Lonja de Mercaderes, is the repository of valuable archival documents preserving the history of the Spanish Empire in the Americas and the Philippines. The structure, an Italianate example of Spanish Renaissance architecture, was designed by Juan de Herrera. The building and its contents were registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

The Casa consistorial de Sevilla is a Plateresque-style building, currently home of the city's government (ayuntamiento), built in 1527–1564. The building was designed by architect Diego de Riaño, who supervised its construction from 1527 until his death in 1534. He was succeeded by Juan Sánchez, who built the arcade which now connects the building with the Plaza Nueva, and later on by Hernán Ruiz the Younger, one of the most accomplished architects of the Plateresque style.[75]

The Hospital de las Cinco Llagas, literally 'Hospital of the Five Holy Wounds' (1546 –1601), is the current seat of the Parliament of Andalusia. Construction of the building began in 1546, as a legacy of Fadrique Enríquez de Ribera, who had died in 1539. It was designed by the architect Martín de Gainza, who supervised its construction until his death in 1556. Two years later, Hernán Ruiz II took charge. The hospital was dedicated, although still incomplete, in 1558.

The College of the Annunciation of the Professed House of the Society of Jesus in Seville was one of the intellectual pillars of the Spanish Counter-Reformation, and also served as a starting point for Jesuit expansion in overseas lands. The building of the Professed House, where the university was installed from 31 December 1771, had been the first residence owned by the Jesuits in Seville. It was founded in February 1558, and work on the church, dedicated to the Annunciation, began in 1565.

The Jesuit supervisor of the House, the architect Bartolome de Bustamante (1501–1570), drew the original plans and the architect Hernán Ruiz the Younger continued the project to its completion in 1568. At first it housed a College for the Humanities, but as early as 1590 it had become the Professed House, a residence for those Jesuits who preached. The Jesuits were expelled from Seville in the 18th century and the building became the seat of the University of Seville in 1771.[76][77] The original structure was torn down in Francoist Spain, but the residence's patio porticoed with marble columns is preserved in the modern Faculty of Fine Arts of the university. The tiny chapel in the Puerta de Jerez, consecrated in 1506, was replaced by the magnificent Church of the Annunciation, built in Renaissance style (1565–1568) as the church of the Professed House. Work on the church with its noble classical facade began in 1565; it was consecrated in 1579. There are some important paintings in the main altarpiece, including The Annunciation by Antonio Mohedano, and the Exaltation of the name of Jesus or Circumcision by Juan de Roelas.

The Royal Audiencia of Seville (Real Audiencia de los Grados de Sevilla) was a court of the Crown of Castile, established in 1525 during the reign of Charles I. It had judicial powers as an appeals court in civil and criminal cases, but had no powers of government. The building that housed the Audiencia of Seville is located in the Plaza de San Francisco de Sevilla, and is currently the headquarters of the financial institution Cajasol. The building was built between 1595 and 1597, although justice had been administered earlier in another building at the same place called the Casa Cuadra since shortly after the reconquest of the city in 1248. The building has been renovated several times.

The Royal Mint of Seville (Casa de la Moneda), built 1585–1587, was the circulation center where gold and silver from the New world were smelted into the Spanish maravedís and doubloons that flowed into and helped support the general European economy in the 16th century, the age of the New World conquistadores and Seville in its full splendor.

The Casa de Pilatos (Pilate's House) serves as the permanent residence of the Dukes of Medinaceli. The building is a mixture of Renaissance Italian and Mudéjar Spanish styles. It is considered the prototype of the Andalusian palace. The construction of this palace, which is adorned with precious azulejos tiles and well-kept gardens, was begun by Pedro Enríquez de Quiñones, Adelantado Mayor of Andalusía, and his wife Catalina de Rivera, founder of the Casa de Alcalá, and completed by Pedro's son Fadrique Enríquez de Rivera, the first Marquis of Tarifa.

The writer Miguel de Cervantes lived primarily in Seville between 1596 and 1600. Because of financial problems, Cervantes worked as a purveyor for the Spanish Armada, and later as a tax collector. In 1597, discrepancies in his accounts of the three years previous landed him in the Royal Prison of Seville for a short time. Rinconete y Cortadillo, a popular comedy among his works, features two young vagabonds who come to Seville, attracted by the riches and disorder that the 16th-century commerce with the Americas had brought to that metropolis.

17th and 18th Centuries

In the 17th century Seville fell into a deep economic and urban decline as a consequence of the general economic crisis that struck Europe and Spain in particular.[78] This decline was aggravated in Seville by river floods and the great plague of 1649, which may have killed some 60,000 people, nearly half of the existing population of 130,000.[79][80] Also at this time the spirit of the Counter-Reformation manifested itself, the Catholic revival transforming Seville into a city of religious convents. By 1671 there were 45 monasteries for monks and 28 convents for women in the city—with all the major orders, Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians and Jesuits, represented in them. This was the social setting of the Holy Week (Semana Santa) processions which had culminated in the Cathedral since Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara issued the mandates of the Synod of 1604, and the origin of the "Carrera Oficial", or Official Path, to the Cathedral.

The devastation caused by the plague of 1649 is depicted in an anonymous canvas in the Hospital del Pozo Santo. Seville's population was halved, a heavy blow to the local economy. One of the plague's most notable victims was the sculptor Martínez Montañés. Discontent spread in the social fabric of Sevillian life, especially among the poor, who rioted in 1652 over the scarcity and high price of bread.

By the late 17th century, the Casa de Contratación had fallen into bureaucratic deadlock, and the empire as a whole was failing because of Spain's inability to finance wars on the Continent and a global empire at the same time. In the 18th century, the new Bourbon kings reduced the power of Seville and the Casa de Contratacion. In 1717 they moved the Casa from Seville to the more suitable harbour of Cádiz, diminishing Seville's importance in international trade. Charles III further limited the powers of the Casa and his son, Charles IV, abolished it altogether in 1790.

The Baroque golden age of Sevillian painting in the 1600s

The economic decline of this period was not accompanied by a corresponding decline of the arts. During the reign of the Habsburg king Philip IV in the 17th century (1621–1665), there were effectively only two patrons of art in Spain—the church and the king with his court. Murillo was the artist favored by the church, while Velázquez was patronised by the crown. The Baroque period of art emphasised exaggerated motion and clear detail to produce drama, exuberance, and grandeur. The popularity of the Baroque style was encouraged by the Catholic Church, which had decided, in response to the Protestant Reformation, that the arts should communicate religious themes in direct and emotional involvement.[81]

The Spanish portrait artist, Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), generally acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of all time, was born in Seville, and lived there for his first twenty-two years. He studied under Francisco de Herrera till he was twelve, and then was apprenticed to his future father-in-law Francisco Pacheco, an active artist and teacher, for six years. By the time he went to Madrid in 1622 his position and reputation were assured.

Zurbarán (1598–1664) is known for his religious paintings depicting monks, nuns, and martyred saints, and for his still lifes. Zurbarán was called the Spanish Caravaggio for his mastery of the realistic use of chiaroscuro. In 1614 his father sent him to Seville to apprentice for three years with Pedro Díaz de Villanueva. The Apotheosis of St. Thomas Aquinas is Zurbarán's most highly regarded work; he painted this starkly realistic masterpiece at the height of his career.[82] Zurbarán made his career in Seville, and in about 1630 he was appointed painter to Philip IV. It was only in 1658, late in his life, that he moved to Madrid in search of work.

Murillo (1617–1682) was born in Seville and lived there this first twenty-six years. He spent two periods of a few years in Madrid, but lived and worked mostly in Seville. He began his art studies under Juan del Castillo, and became familiar with Flemish painting; the great commercial importance of Seville at the time ensured that he was also exposed to influences from other regions. As his painting developed, his works evolved towards the polished style that suited the bourgeois and aristocratic tastes of the time, demonstrated especially in his religious works. In 1642, at the age of 26, he moved to Madrid, where he most likely became familiar with the work of Velázquez, and would have seen the work of Venetian and Flemish masters in the royal collections. In 1660, he returned to Seville, where he died twenty-two years later. Here he was one of the founders of the Academia de Bellas Artes (Academy of Art), sharing its direction, in 1660, with the architect Francisco Herrera the Younger. This was his period of greatest activity, and he received numerous important commissions.

Juan de Valdés Leal (1622–1690) was born in Seville in 1622, and distinguished himself as a painter, sculptor, and architect. He studied under Antonio del Castillo. In 1660 Valdés co-founded the Academia de Bellas Artes with Murillo and Francisco Herrera the Younger. Murillo was the preeminent Sevillian painter of the time and was chosen as president of the academy. After the death of Murillo in 1682, Valdés established himself as the foremost painter in Sevilla. Among his works are History of the Prophet Elias for the church of the Carmelites, Martyrdom of St. Andrew for the church of San Francesco in Córdoba, and Triumph of the Cross for la Caridad in Seville. He died in Seville.

The Museum of Fine Arts of Seville (Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla) houses a choice selection of works by artists from the Golden Age of Sevillian painting during the 17th century, including masterpieces by the above-mentioned masters.

.jpg)

Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649), known as el Dios de la Madera ("the God of Wood"),[83] was one of the most important figures of the Sevillian school of sculpture. In the final quarter of the 16th century, Montañés made his residence in Seville; it would be his base throughout his long life and career. The greatest and most characteristic sculptor of the school of Seville, he produced many important altarpieces and sculptures for numerous places in Spain and the Americas. His works include the great altar at Santa Clara in Seville, the Concepción and the realistic figure of Christ Crucified in Cristo de la Clemencìa in the sacristy of Seville cathedral; and the highly realistic polychromed wood head and hands of St Ignatius of Loyola and of St Francis Xavier in the church of the University of Seville, where the costumed figures were used in celebrations.

Juan de Mesa (1583–1627) was the creator of several of the effigies that are still used in the processions of Semana Santa, including the Cristo del Amor, Jesus del Gran Poder and Cristo de la Buena Muerte. Some of Seville's grandest churches were built in the Baroque period, several of them with retables (altar-pieces) created by accomplished artists; many of the traditional rituals and customs of Holy Week still observed in Seville, including the display of venerated images, date from this time.

At the heart of the Semana Santa (Holy Week) processions are the religious brotherhoods (Hermandades y Cofradías de Penitencia), associations of Catholic laypersons organised to perform public acts of religious observance, in this case acts related to the Passion and death of Jesus Christ and done as a public penance. The hermandades and cofradías (brotherhoods and confraternities) organise the processions during which members precede the pasos dressed in penitential robes, and, with a few exceptions, hoods.

The pasos at the centre of each procession are images or sets of images placed atop a movable float of wood. If a brotherhood has three pasos, the first one would be a sculpted scene of the Passion, or an allegorical scene, known as a misterio (mystery); the second an image of Christ; and the third an image of the Virgin Mary, known as a dolorosa.

The Seminary School of the University of Navigators (Colegio Seminario de la Universidad de Mareantes) was founded in 1681 by the Spanish Crown during the reign of Charles II to "...house, bring up and educate orphaned and abandoned boys for service in the navy and fleets of the Indies". The crown commissioned the building of the Palace of San Telmo (Palacio de San Telmo), named after St. Telmo, the patron saint of sailors, as its seat. This was designed in an exuberant Spanish baroque style by the local architect Leonardo de Figueroa and Matías and Antonio Matías, his son and grandson. This emblem of Seville's civil architecture of the period has since been used for various purposes. It was the residence of the Dukes of Montpensier in the 19th century. During most of the 20th century it was the provincial Seminary, and finally, since 1989, it has been home to the Presidency of the Andalusian Autonomous Government (Junta de Andalucía).

In May 1700, at the beginning of the century of enlightenment and scientific discovery, the Royal Society of Philosophy and Medicine of Seville was founded in Seville, the first of its kind in Spain. Seville lost much of its economic and political importance after 1717, however, when the new Bourbon administration ordered the transfer of the Casa de Contratación from Seville to Cadiz, whose harbour was better suited to transatlantic trade.[84] The Guadalquivir River had been gradually silting in, which was worsened by the effects of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake[85] felt in the buildings of the city, damaging the Giralda and killing nine people.

The Royal Tobacco Factory (Real Fábrica de Tabacos) is an 18th-century stone building. Since the 1950s it has been the seat of the rectorate of the University of Seville. Prior to that, it was, as its name indicates, a tobacco factory—the most prominent such institution in Europe, and a lineal descendant of Europe's first tobacco factory, which was located nearby. One of the first large industrial building projects in modern Europe, the Royal Tobacco Factory is among the most notable and splendid examples of industrial architecture from the era of Spain's Antiguo Régimen. By a Royal Order in 1725 the former tobacco factory was transferred to its current location on land adjacent to the Palace of San Telmo, just outside the Puerta de Jerez (a gate in the city walls). Construction began in 1728, and proceeded intermittently for the next 30 years. It was designed by military engineers from Spain and the Low Countries.[86]

The Royal Tobacco Factory is a remarkable example of 18th century industrial architecture, and one of the oldest buildings of its type in Europe. The building covers a roughly rectangular area of 185 by 147 metres (610 by 480 feet), with slight protrusions at the corners. The only building in Spain that covers a larger surface area is the monastery-palace of El Escorial, which is 207 by 162 metres (680 by 530 feet).[86] Renaissance architecture provides the main points of reference, with Herrerian influences in its floor plan, courtyards, and the details of the façades. There are also motifs reminiscent of the works of the architects Sebastiano Serlio and Palladio. The stone façades are modulated by pilasters on pedestals.[86] This 18th-century industrial building was, at the time it was built, the second largest building in Spain, after the royal residence El Escorial. It remains one of the largest and most architecturally distinguished industrial buildings ever built in that country, and one of the oldest such buildings to survive.

Seville became the dean of the Spanish provincial press in 1758 with the publication of its first newspaper, the Hebdomario útil de Seville, the first to be printed in Spain outside Madrid.

Modern Era

19th Century

The year 1800 in Seville saw an epidemic of yellow fever which spread over the entire city in four months, wiping out a third of the population. It had been introduced into the port of Cádiz with the arrival in July of a corvette coming from Havana, and spread rapidly through the countryside.

When news of the advance of Marshal Claude Victor-Perrin's invading Bonapartist French army arrived in Seville on 18 January 1810, the city erupted in chaos. The Central Junta fled on 23 January and was replaced by a revolutionary government led by Francisco Palafox, the Marquis of La Romana, and Francisco Saavedra, the original head of the Junta of Seville in 1808. Soon discovering how weak the city's defences were, the new Junta absconded as well on 28 January. Anti-Napoleon sentiment was still widespread and the mob remained defiant yet disorganised. When the vanguard of the French troops appeared on 29 January they were fired upon, but the municipal corporation of Seville negotiated a surrender to avoid bloodshed. On 1 February, Marshal Claude Victor occupied the city, accompanied by the pretender to the Spanish throne, Joseph Bonaparte (José I), elder brother of Napoleon Bonaparte.[87] The French settled in until 27 August 1812, when they were forced to retreat by Anglo-Spanish counterattacks; Marshal Soult looted numerous valuable works of art in the interim.

Between 1825 and 1833 Melchor Cano acted as chief architect in Seville, most of the urban planning policy and architectural modifications of the city being made by him and his collaborator Jose Manuel Arjona y Cuba.[88]

In 1833 the government created the administrative province of Seville. In 1835–1837 the Ecclesiastical Confiscations of Mendizábal involved the national confiscation and sale of church property with the intention of creating a large 'family' of proprietors composed of capitalists, landowners, and "hard-working citizens", but ultimately enriched a few among the nobility and the bourgeoisie.[89][90][91] The Liverpool merchant Charles Pickman bought one of the confiscated properties, the abandoned Monastery of Santa Maria de las Cuevas on the Isla de La Cartuja in 1840, and converted it into a factory for ceramic tiles (lozas) and porcelain china. This led to the installation of multiple ovens on the facility (the site continued to produce tiles until 1982, when the factory was transferred to the municipality of Santiponce to allow for development of the island for the Universal Exhibition of 1992). It is now home to the El Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (CAAC),[92] which manages the collections of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Sevilla. It also houses the rectory of the UNIA.[94]

In the years that Queen Isabel II ruled as an adult, the Sevillian bourgeoisie invested in a construction boom unmatched in the city's history. The Isabel II bridge, better known as the Triana bridge, dates from this period. The residence of the Dukes of Montpensier in the Palacio de San Telmo was so extravagant it was said to be vying for second Court of the kingdom. During this period street lighting was expanded in the municipality and most of the streets were paved.[95]

By the second half of the 19th century Seville began an expansion supported by railway construction and the demolition of part of its ancient walls, allowing the urban space of the city to grow eastward and southward. The Sevillana de Electricidad Company was created in 1894 to provide electric power throughout the municipality,[96] and in 1901 the Plaza de Armas railway station was inaugurated. The Museum of Fine Arts (Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla) opened in 1904.

20th Century

Preparations and construction began in 1910 for the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929, a world's fair held in Seville from 9 May 1929 until 21 June 1930. The exhibition buildings were constructed in María Luisa Park along the Guadalquivir River. A majority of the buildings were built to remain permanently after the closing of the exposition. Many of the foreign buildings, including the United States exhibition building, were to be used as consulates after the closing of the exhibits. By the opening of the exposition all of the buildings were complete, although many were no longer new. Not long before the opening, the Spanish government also began a modernization of the city in order to prepare for the expected crowds by erecting new hotels and widening the mediaeval streets to allow for the movement of automobiles.

Spain spent millions of pesetas in developing its exhibits for the fair and constructed elaborate buildings to hold them. The exhibits were designed to show the social and economic progress of Spain as well as expressing its culture. The Spanish architect Aníbal González designed the largest and most famous of the buildings which surrounded the Plaza de España to showcase Spain's industry and technology exhibits. González combined a mix of 1920s Art Deco and 'mock Mudejar', and Neo-Mudéjar styles. The Plaza de España complex is a huge half-circle with buildings continually running around the edge accessible over the moat by numerous beautiful bridges. In the centre is a large fountain. By the walls of the Plaza are many tiled alcoves, each representing a different province of Spain.

The arched drawbridge, the Bridge of San Telmo, was opened in 1931.

The Second Republic and Civil War (1931-1939)

In the country-wide municipal elections held on 12 April 1931 the Republican leftist parties won in the principal Spanish cities. In Seville the Republican Socialists got 57% of the votes versus 39% for the Monarchist coalition. As a result, King Alfonso XIII went into exile and proclaimed the Second Republic.

The convulsions of the Spanish Civil War were fully felt in the Andalusian capital, where since February 1936 the military had been planning a coup. On July 18 General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano quickly gained control of the 2nd División Orgánica, arresting a number of other officers.[97] In poor neighbourhoods such as Triana and La Macarena the unions and leftist parties mobilised militias but Queipo defeated them by a combination of superior weaponry, cunning and harsh repression. Seville was thus occupied by the rebels along with Cadiz and Algeciras, providing General Francisco Franco, Chief of the General Staff, sufficient ground to safely move the Ejército de África (Army of Africa) to Andalusia by air. Seville then became a rearguard city, acting as a bridgehead for the occupation of the rest of the peninsula by the Army of Africa, being the most populous of all the cities occupied by the partisan army. Repression in the city between July 18, 1936 and January 1937 caused the deaths of 3,028 people, including the mayor, Horacio Hermoso Araujo, the Republican former mayor Joseph Gonzalez Fernandez de Labandera, and the president of the Provincial Council, José Manuel de los Santos Puelles. Altogether some 8,000 civilians were shot by the Nationalists in Seville during the course of the war.

Francoist Spain (1939-1975)

On 1 October 1936, in Burgos, Franco was publicly proclaimed as Generalísimo of the National army and Jefe del Estado (Head of State), by the coordinating junta.[98] In Francoist Spain the most powerful officials in Seville and the province were: the military authority embodied in the person occupying the Captaincy General of the Second Military Region, the Civil Government represented by the Provincial Chief of the Movimiento Nacional (Nationalist movement), and the archbishop of the Diocese of Seville. The mayors of the city during this period were directly appointed by the Minister of the Interior, usually those nominated by these military, political and religious authorities.

Under Francisco Franco's rule Spain was officially neutral in World War II (although it did collaborate with the Axis powers),[99][100][101] and like the rest of the country, Seville remained largely economically and culturally isolated from the outside world. One of the most significant events of this period occurred on 13 March 1941 with the explosion of the gunpowder stored in the magazine of Santa Barbara, located in the Cerro del Aguila (Eagle Hill), destroying ten surrounding blocks and damaging many more. Calle José Arpa, where the depot was located, was destroyed, as well as the streets Huesca, Galicia, Lisbon, Afan de Ribera and part of Héroes de Toledo. The magazine was not a military facility, but belonged to the Sociedad Española de Explosivos (Spanish Society of Explosives).

In 1953, during the full autarky of Franco, the shipyard of Seville was opened, eventually employing more than 2,000 workers in the 1970s despite the production of the larger vessels demanded by the maritime market being hindered by the shallowness of the Guadalquivir River.

Before the existence of wetlands regulation in the Guadalquivir basin, Seville suffered regular heavy flooding; perhaps worst of all were the floods that occurred in November 1961 when the river Tamarguillo overflowed as a result of a prodigious downpour of rain in which three hundred litres of water per square metre fell in a short period.[102] Entire neighbourhoods were inundated: La Calzada, Cerro del Águila, San Bernardo, El Fontanal, Tiro de Línea, and La Puerta de Jerez, the waters penetrating as far as La Campana. Seville was consequently declared a disaster zone. A month later, so many Sevillians were still homeless that the popular radio host Bobby Deglané organised a relief motorcade from Madrid, the so-called 'Operación Clavel' (Operation Clavel), which ended in tragedy with the crash of a chartered aeroplane leading the way to publicise the event.[103]

In 1955 the large municipal residential sanitarium, Virgen del Rocio, originally called the Residencia Garcia Morato, was opened. The next fifteen years saw the largest urban expansion of the city yet, with the reconstruction of many neighbourhoods, the upper middle class barrio of Los Remedios exemplifying this urban redevelopment; the Seville Fair, previously held at the Prado de San Sebastián, was moved there in 1973.

Trade unionism in Seville began during the 1960s with the underground organizational activities of the Workers' Commissions or Comisiones Obreras (CCOO), in factories such as Hytasa, the Astilleros shipyards, Hispano Aviación, etc. Several of the movement's leaders were imprisoned in Spain in the Process 1001 of November 1973 by the courts of the Tribunal de Orden Público, including Fernando Soto, Eduardo Saborido, and Francisco Acosta.

Democratic era

On 3 April 1979 Spain held its first democratic municipal elections after the end of Francoist Spain; councillors representing four different political parties were elected in Seville: the Union of the Democratic Centre or Unión de Centro Democrático (UCD) won nine councilors, the Andalusian Party or Partido Andalucista (PA) won eight, the Spanish Socialist Party or Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) won eight as well and the Communist Party of Spain or Partido Comunista de España (PCE) won six. As no party achieved a sufficient majority to govern, a coalition government was formed, with power shared between the PSA, the PSOE and the PCE. The coalition elected Councilman Luis Uruñuela of the Partido Andalucista as mayor.

From 1982 to 1996 the Sevillian politician Felipe González held the Presidency of the Government of Spain.

On 5 November 1982, Pope John Paul II arrived in Seville to officiate at a Mass before more than half a million people at the fairgrounds and celebrate the beatification of Sister (Sor in Spanish) Angela de la Cruz, founder of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross. He visited the city again 13 June 1993, for the International Eucharistic Congress.

In 1992, the Universal Exposition was held for six months in Seville, on the occasion of which the local communications network infrastructure was greatly improved: the SE-30 beltway around the city was completed, new highways were constructed, the new Santa Justa train station had opened in 1991 and the Spanish High Speed Rail system, the Alta Velocidad Española (AVE), began to operate between Madrid-Seville. The Seville airport, the Aeropuerto de Sevilla, was expanded with a new terminal building designed by the architect Rafael Moneo, and various other improvements were made. The monumental Puente del Alamillo (Alamillo Bridge) over the Guadalquivir, designed by the architect Santiago Calatrava, was built to allow access to the island of La Cartuja, site of the massive exposition, as was the Puente de la Barqueta (Barqueta Bridge) designed by Juan J. Arenas and Marcos J. Pantalerón that now connects the historic center of Seville with the technology park. Some of the installations remaining after the exposition at the massive site on La Cartuja island were converted into the largest technology park in Andalusia: the Scientific and Technological Park Cartuja 93. The greenspace and artificial lakes of the Alamillo Park are a legacy of the exposition as well; the present theme park, Isla Mágica, is a re-purposing of the Lago de España zone of the exposition.

Throughout the decade there were several attacks in Seville by the Basque separatist group ETA resulting in deaths. On 30 January 1998, the deputy mayor of Seville and member of the People's Party, Alberto Jiménez-Becerril Barrio and his wife, Ascension Garcia Ortiz, attorney of the courts of Seville, were assassinated at their home, leaving three children; in October 2000 the military physician Colonel Antonio Muñoz Cariñanos was shot dead in his own office. These killings provoked great consternation in the city and led to massive demonstrations against ETA violence.

21st Century

Seville began the century under the leadership of the socialist Mayor Alfredo Sanchez Monteseirín (PSOE), who had held the position of alderman since June 1999 with support from the PA, the PP being the largest party. In 2003 he was again invested as mayor, winning this time as the candidate with the most popular votes but not an absolute majority, and in this case supported by the councilors of the United Left. The outcome of the elections in May 2007 validated the progressive pact of the (PSOE-IU), surpassing the number of votes submitted by the People's Party (PP) or the Andalusian Party (PA), leaving the latter without representation in the council and the PP with the most votes of all the parties represented in the Consistorio. Thus Sánchez Monteseirín ranks as the first mayor in the history of democracy in Seville to serve three times on the city council in power, despite having been only once the candidate with the most votes from the electorate and the filing of corruption charges of illegal financing through the issue of false invoices.

In June 2002 a summit of the Heads of State and Government of the European Union was held in Seville, chaired by the then acting president of the European Union and the Spanish president, José María Aznar. The meeting was protested with a series of actions and peaceful mass demonstrations by alternative and anti-capitalist political action groups.

In 2003, construction of Line 1 of the Metro de Sevilla was reinitiated, having been canceled in 1983 due to technical difficulties in the subsurface excavation, with cracks appearing in several historic buildings in the city. The project was restarted in 1999 on a different layout to the original, focussing less on urban locations and more on the broader metropolitan area; the work resumed with an intense effort by the Sociedad Metro de Sevilla (Society of Metro Seville), driven by Andalucista Alejandro Rojas-Marcos and local government to complete the construction of the metro. The completion of its four lines will be a milestone in the history of the communications-saturated metropolitan area of Seville.

In 2004 the Sevillian brewer Cruzcampo celebrated its centenary, organizing numerous public events and advertising campaigns to celebrate the anniversary. Also in 2004 the conservative newspaper ABC, founded in 1929 by Torcuato Luca de Tena, marked its 75th anniversary in the Seville edition.

2005 marked the centenary of Sevilla FC (Sevilla Football Club) and in 2007 of the Real Betis Balompié club.

Work on the Metro Line 1 should have been completed by June 2006, but changes in layout, unanticipated archaeological finds, problems with tunneling and shafts, and work stoppages of various kinds prompted the Junta de Andalucía to not set any date prior to 2008 for its inauguration and shuffle the projected date of full operation to early 2009.

In February 2007 the bidding process started for works of the remaining lines (2, 3 and 4) to complete the projected metro network; the regional government of Andalusia (Junta de Andalucía) and the national government being responsible for funding Lines 2 and 3 of the metropolitan layout and the city of Seville responsible for financing construction of the urban Line 4. The metro will include tram lines—the Metrocentro in the center of the city, the tram Aljarafe, and the tram Alcala de Guadaira—all connected with Metro Line 1 to provide a comprehensive transportation system.

The empowerment of local lines will be emphasised as well with rail ringing the city, and new connections to the North Aljarafe (Sanlucar la Mayor, etc.). In 2007 and 2008, major media attention-grabbing projects included: the building of a network of bike paths that made Seville the city with the greatest total length of bike lanes in Spain; the pedestrianization of the Plaza Nueva and Constitution Avenue (next to the Cathedral); the operationalising of the Metrocentro tram that links the Prado de San Sebastián with the aforementioned Plaza Nueva; the construction of the César Pelli-designed office tower (scheduled to be finished in 2013) as headquarters for the newly formed Cajasol bank; the international award-winning architectural project "The setas"; the redevelopment in the Alameda de Hercules, and planned upgrades to the gardens and port along the Paseo de las Delicias, the port being redeveloped to accommodate more visits by cruise ships to the city; and a new aquarium, the New World Aquarium at Muelle de Las Delicias.

Although Los Astilleros, the Seville shipyard, closed in late 2011[104] after suffering financial[105] and labor[106] difficulties, Seville's economy is steadily improving with a mix of tourism, commerce, technology and industry.

Population

| Date | Population[107][108][109][110] | |

|---|---|---|

| 12th century | 80,000 | |

| 1275 | 24,000 | |

| 1384 | 15,000 | |

| 1430 | 25,000 | |

| 1490 | 35–40,000 | |

| 2026 | 50,000 | |

| 1533 | 55–60,000 | |

| 1588 | 129,430 | |

| 1591 | 115,830 | |

| 1597 | 121,505 | |

| 1649 | 120,000 | |

| 1650 | 60–65,000 | |

| 1705 | 85,000 | |

| 1750 | 65,000 | |

| 1800 | 80,598 | |

| 1804 | 65,000 | |

| 1821 | 75,000 | |

| 1832 | 96,683 | |

| 1857 | 112,529 | |

| 1860 | 118,298 | |

| 1877 | 134,318 | |

| 1884 | 133,158 | |

| 1877 | 143,182 | |

| 1900 | 148,315 | |

See also

References

- This article incorporates information translated from the equivalent article on the Spanish Wikipedia.

Notes

- Glaire D. Anderson; Mariam Rosser-Owen (2007). Revisiting Al-Andalus: Perspectives on the Material Culture of Islamic Iberia and Beyond. BRILL. p. 150. ISBN 90-04-16227-5.

- Manuel Jesús Roldán Salgueiro (2007). Historia de Sevilla. Almuzara. ISBN 978-84-88586-24-7. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- José María de Mena (1985). Historia de Sevilla. Plaza & Janés. p. 39. ISBN 978-84-01-37200-1. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Proyecto Puntual de Investigación 1999: Intervención Puntual: "Estudios estratigráficos y análisis constructivos"". Real Alcázar (in Spanish). Real Alcázar de Sevilla. Archived from the original on 2013-08-15.

Los restos antrópicos más antiguos se situaban sobre esta terraza, bajo la muralla Septentrional del Alcázar, datados en el s. VII-VIII a.C.

- Luis Suárez Fernández; Manuel Bendala Galán (1987). Historia General de España y América: De la Protohistoria a la Conquista Romana: Tomo I-2. Ediciones Rialp. p. 149. ISBN 978-84-321-2096-1. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Michael Dietler; Carolina López-Ruiz (15 October 2009). Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. University of Chicago Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-226-14848-9.

- Robin Osborne; Barry Cunliffe (27 October 2005). Mediterranean Urbanization 800-600 BC. Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-726325-9.

- Andrew G. Traver (2002). From Polis to Empire: The Ancient World, C. 800 B.c. - A.d. 500 : a Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-313-30942-7. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Elizabeth Nash (16 September 2005). Seville, Cordoba, and Granada : A Cultural History: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-972537-3.

- Isidore of Seville's Etymologies: Complete English Translation. Lulu.com. 2005. p. 350. ISBN 978-1-4116-6526-2.

- Ordóñez Agulla, Salvador (2002). "Sevilla Romana". In Magdalena Valor Piechotta (ed.). Edades de Sevilla: Hispalis, Isbiliya, Sevilla (in Spanish). Sevilla: Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, Area de Cultura Área de Cultura y Fiestas Mayores. p. 27. ISBN 84-95020-92-0. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

Si bien algún autor antiguo indica expresamente que el Baetis estaba canalizado por todas las ciudades a su paso, hoy por hoy las únicas áreas urbanas de las que se tiene constancia expresa de su funcionalidad portuaria son el gran embarcadero de pilotes de madera, con restos documentados tanto en la calle Sierpes como en la Plaza de San Francisco, y los varios pecios de la Plaza Nueva, que permiten pensar que en estos puntos se situaban los lugares de atraque, carga y descarga y fondeaderos, sobre distancias considerables.

- Diego A. Cardoso Bueno (1 January 2006). Sevilla, El Casco Antiguo: Historia, Arte Y Urbanismo. Guadalquivir Ediciones. ISBN 978-84-8093-154-0. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Juan M. Campos Carrasco (1 January 1986). Excavaciones arqueológicas en la ciudad de Sevilla: el origen prerromano y la Híspalis romana. Monte de Piedad y Caja de Ahorros de Sevilla. p. 11.

- Matthew Bunson (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-4381-1027-1.

- David Farmer (14 April 2011). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Fifth Edition Revised. Oxford University Press. p. 249. ISBN 0-19-959660-3.

- Kenneth Baxter Wolf (1 January 1999). Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain. Liverpool University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-85323-554-5.

- Orientalia Lovaniensia periodica. Instituut voor Oriëntalistiek. 1983. p. 100.

- José María de Mena (1992). Art and History of Seville. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 5. ISBN 978-88-7009-851-8.

- Isidorus (Hispalensis) (8 June 2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-139-45616-6.

- Ana Ruiz (2007). Vibrant Andalusia: The Spice of Life in Southern Spain. Algora Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-87586-539-3.

- George O. Cox (1974). African Empires and Civilizations: Ancient and Medieval. African Heritage Studies Publishers. p. 135.

- Michael Frassetto (31 March 2013). The Early Medieval World. ABC-CLIO. p. 490. ISBN 978-1-59884-996-7.

- Revue hispanique: recueil consacré á l'étude des langues, des littératures et de l'histoire des pays castillans, catalans et portugais. A. Picard et fils. 1902. p. 39.

- E. J. Van Donzel (1 January 1994). Islamic Desk Reference. BRILL. p. 8. ISBN 90-04-09738-4.

- Mishal Fahm al-Sulami (6 January 2004). West and Islam. Routledge. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-134-37405-2.

- P. M. Holt; Peter Malcolm Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (21 April 1977). The Cambridge History of Islam:. Cambridge University Press. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- David Wasserstein (1993). The caliphate in the West: an Islamic political institution in the Iberian peninsula. Clarendon Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-19-820301-8.

- Historia de Sevilla. Universidad de Sevilla. 1992. p. 124. ISBN 978-84-7405-818-5.

- Moreno, Eduardo Manzano (1998). "The Social Structure of al-Andalus during the Muslim Occupation (711–755) and the Founding of the Umayyad Monarchy". In Marin, Manuela (ed.). The Formation of al-Andalus, Part 1: History and Society. New York: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 102–103. ISBN 9780860787082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh (1996). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus (First ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 32, 35–36. ISBN 0-582-49515-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fierro, Maribel (2011). "The Battle of the Ditch (al-Khandaq) of the Cordoban Caliph ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III". In Ahmed, Asad Q.; Sadeghi, Benham; Bonner, Michael (eds.). The Islamic Scholarly Tradition: Studies in History, Law, and Thought in Honour of Professor Michael Allen Cook. Leiden and Boston: Brill. p. 109. ISBN 978-90-04-19435-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Granado, José Miguel (octubre de 1999), Mezquita de Ibn Adabbas de Sevilla Archived 2010-04-10 at the Wayback Machine, in Revista Aparejadores, no. 56, Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Sevilla. [19-10-2008]

- Gwyn Jones (2001). A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-19-280134-0.

- Dreyer (Firm) (November 1996). "Norsk jul i bokform". The Norseman. Nordmanns-forbundet. 36 (6): 16. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Stefan Brink; Neil Price (31 October 2008). The Viking World. Routledge. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-203-41277-0.

- Riosalido, Jesús (1997). "Los vikingos en al-Andalus" (PDF). Al-Andalus Magreb. 5: 335–344. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Muḥammad ibn ʻUmar Ibn al-Qūṭīyah (2009). Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn Al-Qūṭīya : a Study of the Unique Arabic Manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, with a Translation, Notes, and Comments. Taylor & Francis. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-415-47552-5.

- The Cambridge Medieval History. Camb. University Press. 1986. p. 395.

- Nathaniel Armstrong Wells (1846). The picturesque antiquities of Spain: described in a series of letters, with illustrations, representing Moorish palaces, cathedrals, and other monuments of art, contained in the cities of Burgos, Valladolid, Toledo and Seville. R. Bentley. pp. 343.

- Christopher Turner (1992). The Penguin Guide to Seville. Penguin. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-14-015785-7.

- Amadó, Ramón Ruiz (1912). "Seville". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Ira M. Lapidus (29 October 2012). Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 379–. ISBN 978-0-521-51441-5.

- Francisco Bueno; Francisco Bueno Manso. Jardines de Sevilla. Del Jardín Histórico al Jardín actual. Francisco Bueno Manso. p. 11. GGKEY:J846GCFAP25. Retrieved 9 February 2013.