Hippocampinae

The Hippocampinae are a subfamily of small marine fishes in the family Syngnathidae. Depending on the classification system used, it comprises either seahorses and pygmy pipehorses,[1] or only seahorses.[2]

| Hippocampinae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Idiotropiscis australe | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | Hippocampinae |

| Genera | |

|

Between 1 and 6 (see text) | |

Genera

Seahorses

- Hippocampus Rafinesque, 1810

- Up to 54 species of seahorses

Pygmy pipehorses

- Acentronura Kaup, 1853

- Acentronura gracilissima (Temminck & Schlegel, 1850) (bastard seahorse)

- Acentronura tentaculata (Günther, 1870) (shortpouch pygmy pipehorse)

- Amphelikturus Parr, 1930

- Amphelikturus dendriticus (T. Barbour, 1905) (pipehorse)

- †Hippotropiscis Žalohar & Hitij, 2012 (known only from Miocene fossils)[3]

- Hippotropiscis frenki Žalohar & Hitij, 2012[3]

- Idiotropiscis Whitley, 1947

- Idiotropiscis australe (Waite & Hale, 1921) (southern little pipehorse)

- Idiotropiscis larsonae (C. E. Dawson, 1984) (Helen's pygmy pipehorse)

- Idiotropiscis lumnitzeri Kuiter, 2004 (Sydney's pygmy pipehorse)

Description

All seahorse and pygmy pipehorse species have a prehensile tail (a character shared with some other syngnathids),[4] a fully enclosed brood pouch, a short head and snout angled ventrally from the abdominal axis, and no caudal fin.[5] The species in the genera Acentronura, Amphelikturus and Kyonemichtys resemble pipefishes, which explains why pygmy pipehorses are sometimes grouped in the pipefish subfamily Syngnathinae.[6] The species of Idiotropiscis are more seahorse-like in appearance in having a deeper body and discontinuous superior trunk and tail ridges.[7] The main differences between this pygmy pipehorse genus and the seahorses is that the latter have an upright posture, and the angle of their head relative to the abdominal axis is greater.[7]

Etymology

The subfamily Hippocampinae is named after the seahorse genus Hippocampus, which is derived from the Ancient Greek ἱππόκαμπος (hippokampos), a compound of ἵππος, "horse" and κάμπος, "sea monster". The morphologically intermediate nature of pygmy pipehorses is reflected in the name "pipehorse", a combination of the first syllable of "pipefish" and the second syllable of "seahorse". "Pygmy" is added to distinguish them from the larger pipehorses of the genus Solegnathus, which are distant relatives of the pygmy pipehorses.[8] Other common names that have been applied to pygmy pipehorses include "bastard seahorse", "little pipehorse" and "pygmy pipedragon".

Systematics

Due to the morphologically intermediate nature of the pygmy pipehorses between pipefishes and seahorses, the taxonomic placement of this group remains contentious, and three different classifications have been proposed for the subfamily Hippocampinae. No well-resolved phylogeny exists, making it impossible to settle this issue at the present time.

- Hippocampinae comprises both seahorses and pygmy pipehorses[1]

- Phylogenetic analyses based on five nuclear genetic loci recovered the genera Hippocampus and Idiotropiscis as sister taxa, suggesting that seahorses and pygmy pipehorses are a monophyletic group[9] and hence share a common evolutionary origin. However, the same phylogeny indicates that if the subfamily Hippocampinae is accepted as valid, then the pipefish subfamily Syngnathinae is paraphyletic, because the former is not a sister group of the latter, but is nested within it.[9]

- Hippocampinae includes only seahorses, pygmy pipehorses are placed into the pipefish subfamily Syngnathinae[6]

- This classification system disregards both genetic data and the morphological characters shared by seahorses and pygmy pipehorses. As seahorses have a sister taxon relationship with Idiotropiscis, and other pygmy pipehorse genera are likely basal to this group (given their more pipefish-like appearance), this classification would also make the Syngnathinae paraphyletic.

- Hippocampinae includes only seahorses, pygmy pipehorses are placed into own subfamily[2]

- This classification places all pygmy pipehorses into the subfamily Acentronurinae. Based on the nuclear DNA phylogeny, the exclusion of the seahorses from this group likely makes it paraphyletic. However, such a placement is partially supported by an alternative molecular phylogeny that is based on a combination of nuclear and mitochondrial markers and that recovered a group comprising pygmy pipehorses and several pipefishes as a sister lineage of Hippocampus.[10]

As the genus Hippocampus consists of two morphologically distinct forms, it has been suggested that it should be split into two distinct genera, Hippocampus and a new genus comprising the pygmy seahorses. Pygmy seahorses have a single gill opening on the back of the head (instead of two on the sides as in normal seahorses), and the males brood their young inside their trunk, instead of in a pouch on the tail.[11] A molecular phylogeny confirms that the pygmy seahorses are a monophyletic sister lineage of all other seahorses.[10]

Acentronura breviperula, a species of pygmy pipehorse that looks like a short pipefish

Acentronura breviperula, a species of pygmy pipehorse that looks like a short pipefish

The Australian potbelly seahorse, Hippocampus abdominalis, the largest species in the subfamily Hippocampinae.

The Australian potbelly seahorse, Hippocampus abdominalis, the largest species in the subfamily Hippocampinae.

Evolution and fossil record

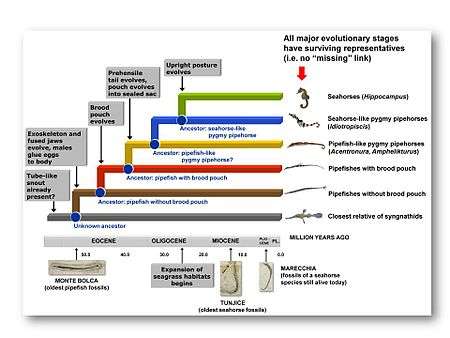

The morphology of pygmy pipehorses suggests that they are an evolutionary link between pipefishes and seahorses, and that seahorses are upright-swimming pygmy pipehorses. Molecular dating indicates that Hippocampus and Idiotropiscis diverged from a common ancestor during the Late Oligocene.[9] During this time, tectonic events in the Indo-West Pacific resulted in the formation of shallow-water areas, which considerably changed marine habitats in this region.[12] Particularly important was the establishment of vast seagrass meadows where there had previously been deeper water.[13] This has led to speculation that the earliest seahorses managed to establish themselves as a new species because, unlike pygmy pipehorses, they were selectively favoured in such habitats. Not only can seahorses manoeuver exceptionally well in dense seagrass meadows,[14] but the upright seagrass blades would have provided camouflage for their bodies and in that way improved their ability to ambush prey and avoid detection by predators.[9] An alternative explanation for the evolution from pygmy pipehorse to seahorse is based on the finding that a vertically-bent head is more efficient in capturing prey because it increases the animal's strike distance, which is considered particularly useful in tail-attached sit-and-wait predators.[15] In that case, the evolution of an upright posture would merely be a means of maximising the angle between head and abdominal axis.

There is as yet no fossil evidence for the evolution of seahorses from a pygmy pipehorse ancestor, as the fossil record of both groups is very sparse. The only pygmy pipehorse species of which fossils have been found (Hippotropiscis frenki) lived in the Central Paratethys Sea (the modern-day Tunjice Hills of Slovenia, north of the Mediterranean Sea) during the Middle Miocene,[3] i.e. during a time when seahorses had already evolved.[9] In fact, the oldest known seahorse species, Hippocampus sarmaticus and H. slovenicus, were found at the same site.[3] Independent geological confirmation of the genetic data would require finding a fossil site from the Oligocene in which seahorse-like pygmy pipehorses are present, but seahorses are not. Given the fact that Idiotropiscis is endemic to temperate Australia and the most basal seahorse lineages occur in Australia and the tropical West Pacific,[16] these regions are the most likely candidates for such a site.

References

- Kuiter, R.H. (2000) "Seahorses, Pipefishes and their Relatives — A Comprehensive Guide to Syngnathiformes." TMC Publishing, Chorleywood, UK.

- Wilson N., Rouse G. (2010). "Convergent camouflage and the non-monophyly of 'seadragons' (Syngnathidae: Teleostei): suggestions for a revised taxonomy of syngnathids". Zoologica Scripta. 39: 551–558. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2010.00449.x.

- Žalohar, J.; Hitij, B. (2012). "The first known fossil record of pygmy pipehorses (Teleostei: Syngnathidae: Hippocampinae) from the Miocene Coprolitic Horizon, Tunjice Hills, Slovenia". Annales de Paléontologie. 98 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2012.02.003.

- Dawson, C.E. (1982). "Review of the Indo-Pacific pipefish genus Stigmatopora (Syngnathidae)". Records of the Australian Museum. 34 (13): 575–605. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.34.1982.243.

- Gomon, M.F. (2007). "A new genus and miniature species of pipehorse (Syngnathidae) from Indonesia". aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology. 13 (1).

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2013). "Acentronura tentaculata" in FishBase. May 2013 version.

- Kuiter, R.H. (2004). "A New Pygmy Pipehorse (Pisces: Syngnathidae: Idiotropiscis) from Eastern Australia" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 56 (2): 163–165. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.56.2004.1420.

- Wilson, A.B., Ahnesjö, I., Vincent, A.C. and Meyer, A. (2003). "The dynamics of male brooding, mating patterns, and sex roles in pipefishes and seahorses (family Syngnathidae)". Evolution. 57 (6): 1374–1386. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00345.x. PMID 12894945.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Teske, P.R.; Beheregaray, L.B. (2009). "Evolution of seahorses' upright posture was linked to Oligocene expansion of seagrass habitats". Biology Letters. 5 (4): 521–523. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0152. PMC 2781918. PMID 19451164.

- Healy Hamilton, Norah Saarman, Beth Moore, Graham Short, & W. Brian Simison: A Multigene Phylogeny of Syngnathid Fishes. PDF Archived 21 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, Richard E. Pygmy seahorse research

- Wilson, M. E. J. & Rosen, B. R. 1998 Implications of paucity of corals in the Paleogene of SE Asia: plate tectonics or centre of origin? In Biogeography and geological evolution of SE Asia (eds R. Hall & J. D. Holloway), pp. 165–195. Leiden, The Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers.

- Brasier, M.D. (1975). "An outline history of seagrass communities". Palaeontology. 18: 681–702.

- Flynn, A. J.; Ritz, D. A. (1999). "Effect of habitat complexity and predatory style on the capture success of fish feeding on aggregated prey". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 79 (3): 487–494. doi:10.1017/S0025315498000617.

- van Wassenbergh, S., Roos, G. and Ferry, L.; Roos; Ferry (2011). "An adaptive explanation for the horse-like shape of seahorses". Nature Communications. 2 (1): 164. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2E.164V. doi:10.1038/ncomms1168. PMID 21266964.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Teske PR, Cherry MI, Matthee CA (2004). "The evolutionary history of seahorses (Syngnathidae: Hippocampus): molecular data suggest a West Pacific origin and two invasions of the Atlantic Ocean". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (2): 273–86. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00214-8. PMID 14715220.

External links

- {{EOL}} template missing ID and not present in Wikidata.

- Pictures: Ancient pygmy pipehorse species found National Geographic, 8 May 2012.

- How seahorses evolved to swim "standing up" National Geographic News, 22 May 2009

- How the seahorse got its shape Nature Video, 21 January 2011

- Sydney's pygmy pipehorse Australian Museum 14 September 2012

- Wakatobi pygmy pipehorse Wakatobi Dive Resort